124 Reports

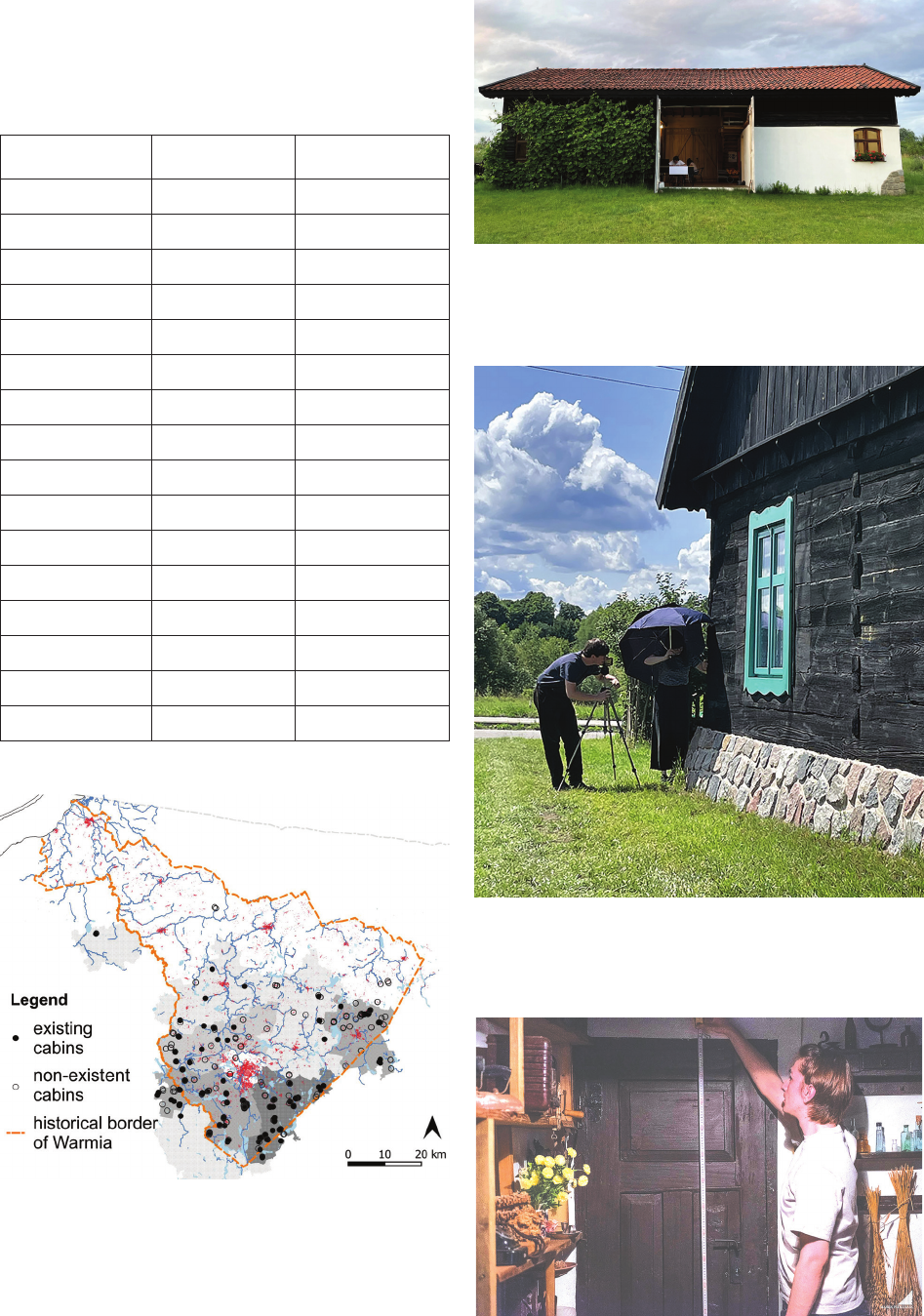

structions or dismantling of the original buildings. On the

other, however, these structures are also preserved from

deterioration and loss as a good place to live. There are

people who decide to restore them and live in them. The

observed trend for disappearance of log cabins in Warmia

and, at the same time, for their recovery has fuelled the

need to record and re-analyse the structure of these build-

ings as well as to examine sociological aspects of their use

as homes, both in the past and in the present. To obtain the

most complex representation of the functional use of the

houses included in the study, for each building the follow-

ing information was gathered during the workshops:

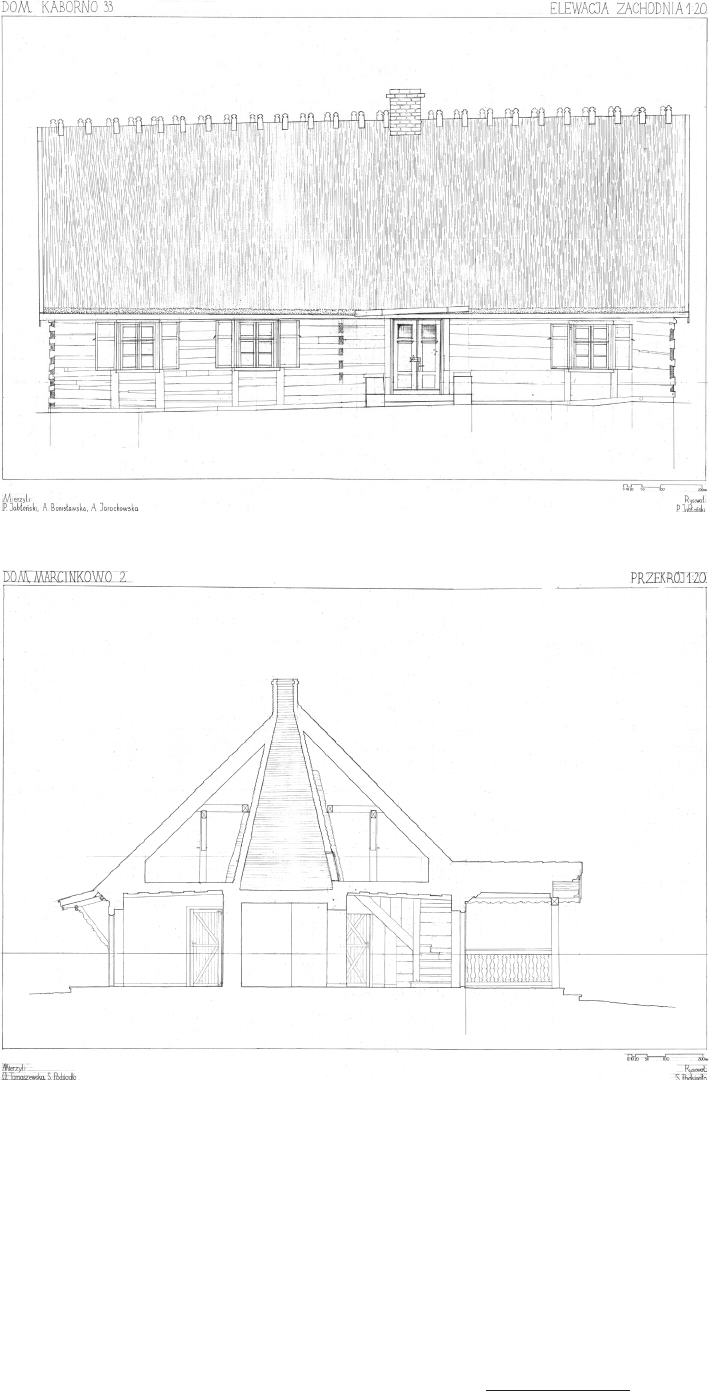

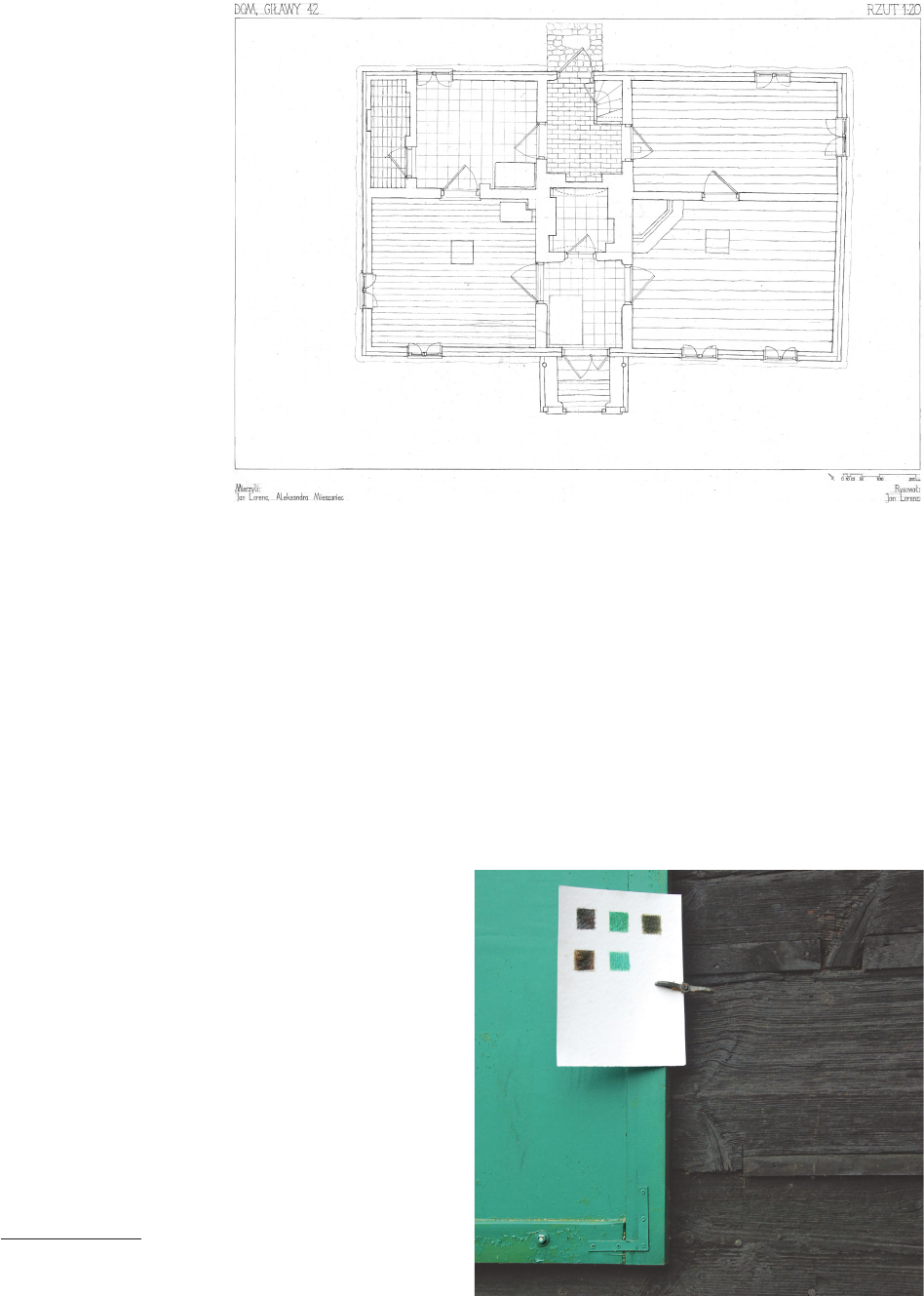

– an architectural and structural survey based on hand-

drawn drawings: oor plans, cross-sections and four eleva-

tions, at a scale of 1:20,

– colour samples of external wall beams as well as win-

dow and door woodwork,

– recordings and transcriptions of ethnographic inter-

views with residents about the past and present of resi-

dence and the technical condition of their houses.

In addition, detailed photographs and video footage

were recorded using a drone (operator and photographer:

Stanisław Podsiadło). All forms of recording information

collected during the workshops (scans of inventory draw-

ings, transcriptions and audio recordings of interviews,

drone material, selected photographs) were provided on

external storage media to the residents of the surveyed

houses, and the original drawing documentation was de-

posited in the archives of the Department of Polish Ar-

chitecture, Faculty of Architecture, Warsaw University of

Technology.

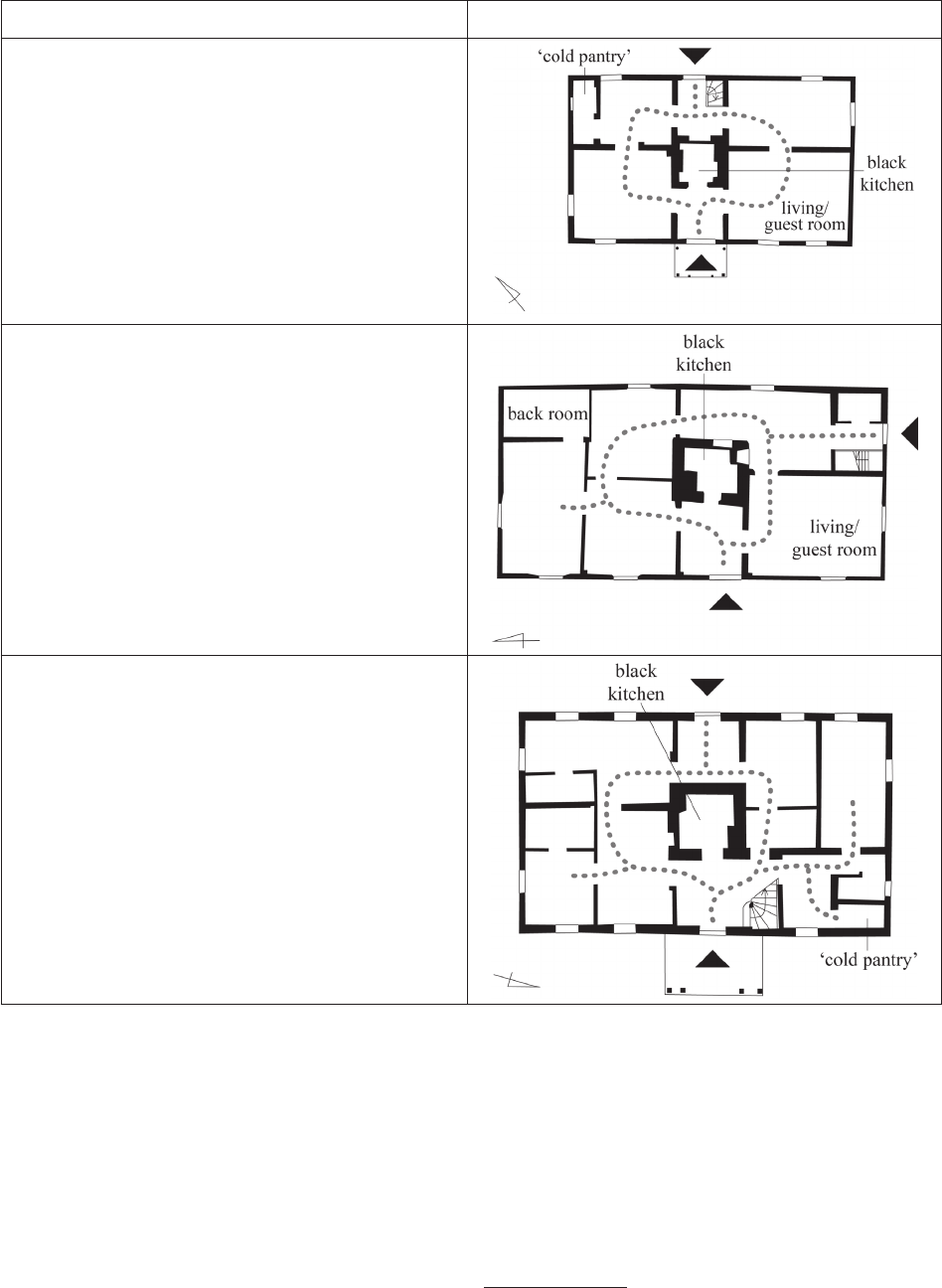

The workshops led to recording of the functional prop-

erties of the structure of log cabins in the Warmia Region

and their usability values based on declarations from their

present owners. The resulting records can serve for the pre -

servation and continuation of the existing heritage. The

complex fate of the three studied houses and their inhabi-

tants was also traced, from the time of construction, through

the period of their functioning in the Warmian culture, to

the migration of people in the post-war period and to the

present day. This is a rich material supporting research on

the issues of perception and formation of Warmia’s region-

al identity

2

and cultural landscape today

3

.

2

Research on the identity of the people of Warmia is carried out,

among others, by Izabela Lewandowska [1]. The complex nature of this

issue, due to the fact that before World War II Warmia and Masuria be-

longed to Germany, and after the War, these areas were incorporated

into Poland, is researched by sociologists and historians, e.g., Anna Szy-

fer [2], Andrzej Sakson and Robert Traba [3].

3

The phenomenon of transformation of the cultural landscape ap-

plies especially to the 2

nd

half of the 19

th

century and the interwar period

– and therefore to the area of East Prussia, and then to the changes that

have been ongoing in Warmia since the Polish People’s Republic until

today, already under the Third Polish Republic. Social migrations had

signicantly contributed to disrupting continuous development of these

areas. A similar phenomenon has been observed in other areas of the

Prussian Partition, which today is termed as the so-called post-German

heritage in the cultural landscape. An interesting analysis was carried

out by Filip Springer [4], where he explains the resulting relationships

between the power, evolution of the industrial era and cultural inuences

as the factors that have shaped the area where we live today.

State of the research:

The architectural heritage of log houses

in the Warmia Region

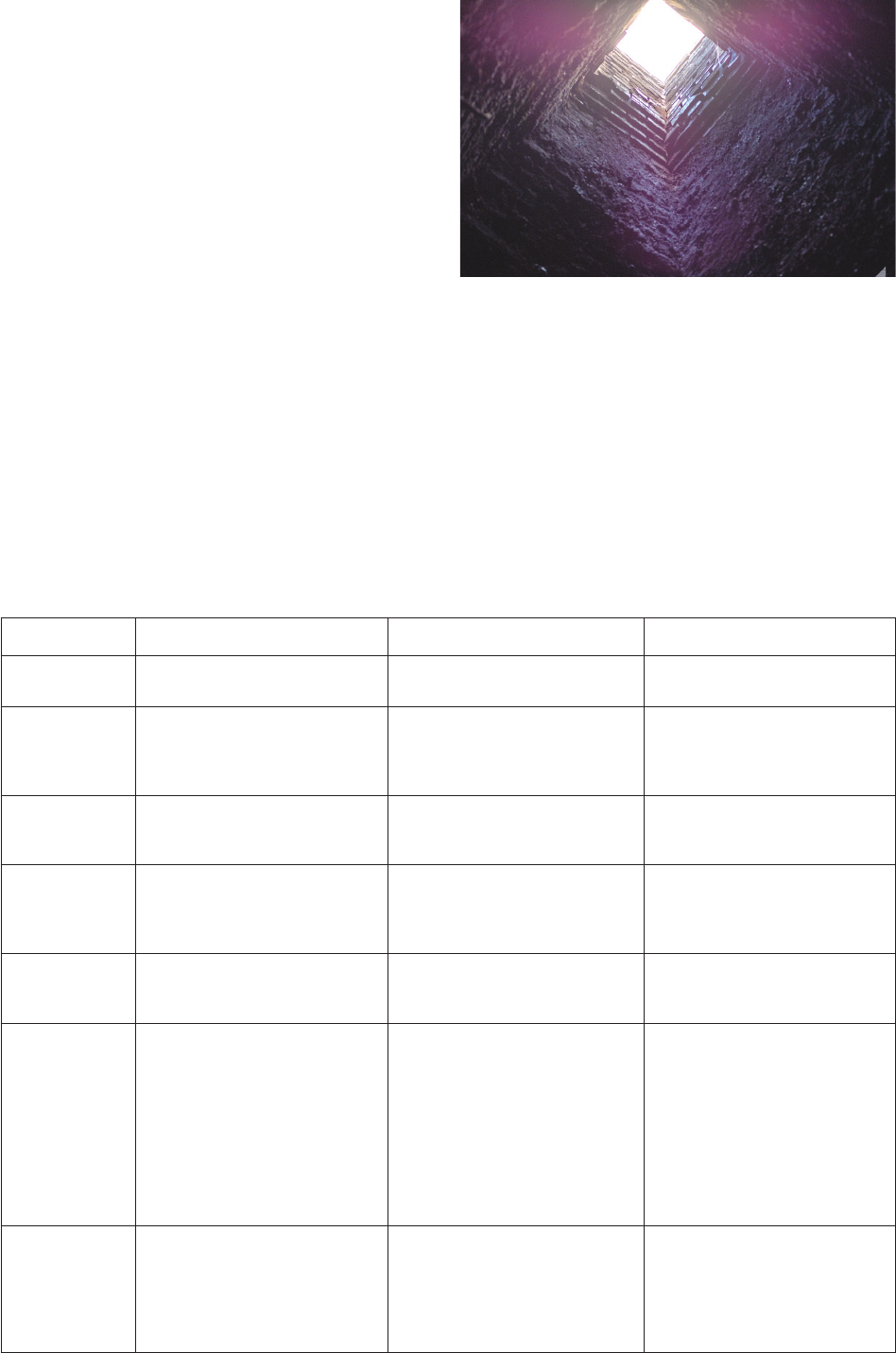

The study area for researching Warmian cabins was de-

ned based on the historical border of the Warmia Region

4

.

The territory of the Diocese of Warmia, where the chapter

and bishopric of Warmia were established, changed slight-

ly in its shape between 1243 and 1772. Initially an auton-

omous entity managed by bishops, the area was incorpo-

rated into the Kingdom of Poland in 1525. Catholicism

determined the cultural distinctiveness of Warmia from the

then surrounding Duchy of Prussia, where protestantism

was growing popular in the 16

th

and 17

th

centuries. These

dierences began to fade when, together with Masuria and

Powiśle, the area went under the administration of East

Prussia from 1772 until 1945. An extensive and detailed

account of the history of Warmia and Masuria was writ-

ten by historian Stanisław Achremczyk [5]. The distinctive

character of the lands of Warmia and Masuria is noticeable

to this day, because the historical factors of religious al-

iation and dominant power inuenced how the local cul-

tural landscape evolved [6]. Of relevance to maintaining

the dierences was also the ethnographic factor, because

native inhabitants of Warmian and Masuria are identied

(also by themselves) as two distinct ethnic groups [2].

Since the 1950s, studies have been written by Polish re-

searchers who are rediscovering the environment and cul-

tural heritage of these areas. In the series Ziemie staropol-

skie [Old Polish Lands], published for Warmia and Mazury

in two volumes in 1953, we nd, e.g., a study by Hieronim

Skurpski [7], painter and cultural activist, that contains

references to folk art which is considered to include ru-

ral wooden constructions. A detailed distinction between

the typical cabins of Masuria and Warmia can be found in

Franciszek Klonowski’s book titled Drewniane budown-

ictwo ludowe na Mazurach i Warmii [Wooden Folk Ar-

chitecture in Masuria and Warmia] released in 1965 [8],

with maps showing the locations of individual structures

– approximately 300 existing buildings in the Warmia Re-

gion

5

. This study is also valuable as it contains a collection

of photographs of non-existing structures (the collection is

kept in the archives of the Museum of Warmia and Masur-

ia) and a detailed description of technical and ethnographic

details. This topic is also treated by authors such as Ignacy

Tłoczek [9] and Marian Pokropek [10], in whose works

folk structures of Warmia and Masuria make part of stud-

ies on the wooden architecture heritage in Poland. In their

publications, however, a typical rural house of the Warmia

4

The scope of the study area is determined by the historical border

of Warmia. It was adopted on the basis of a study by Piotr Nawacki,

author of the numerical outline of this border in the GIS format. Nawacki

has authored a number of tourist maps covering Warmia and Masuria.

He determined the historical border of the Warmia Region based on his-

torical German maps (e.g., Jan Fryderyk Endersch’s map dated 1755,

[5, p. 18]) and eld studies. The resulting outline was provided to the

study authors as a layer source in the .json format for research purposes,

https://warmaz.pl/granica-warmii/ [accessed: 12.09.2023].

5

According to the records from the 1960s [8, pp. 50–52].