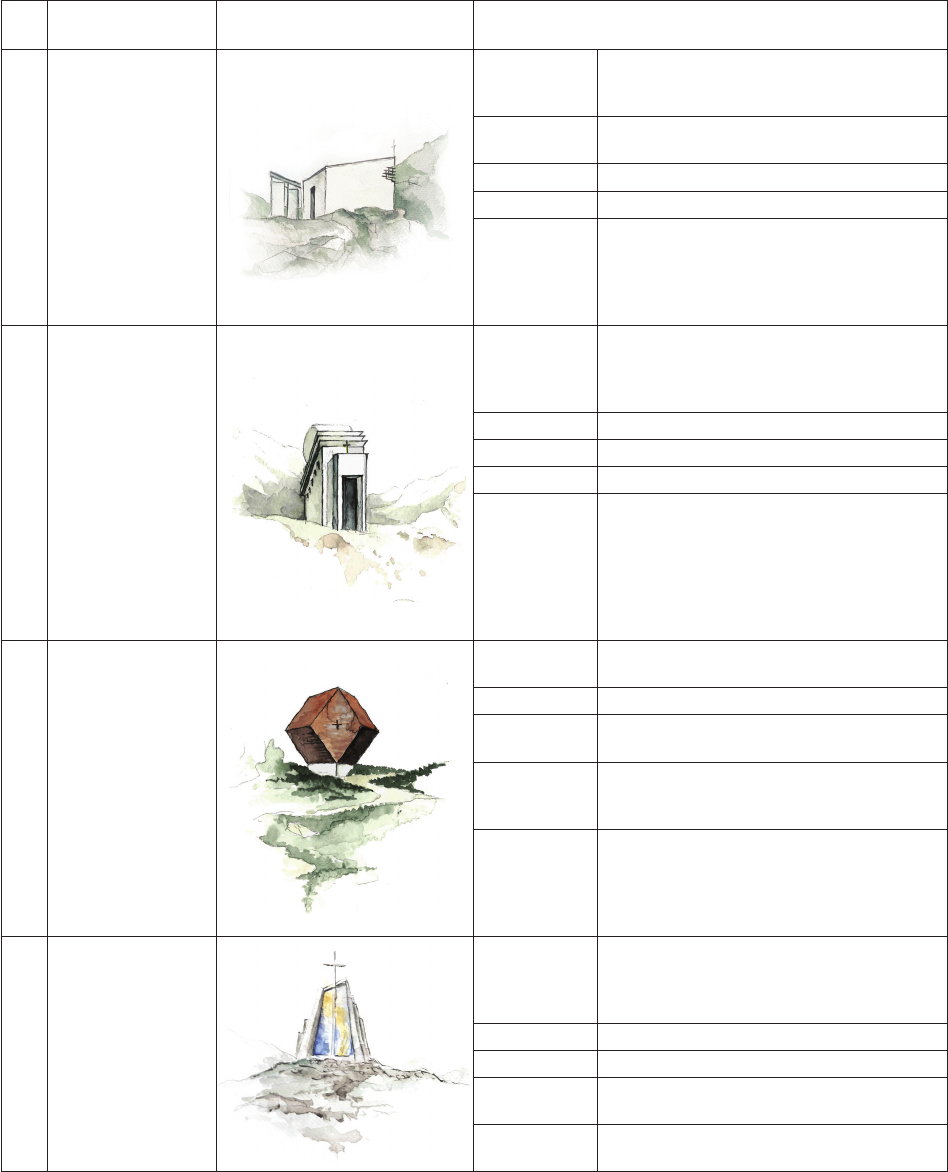

Forms of sacred buildings inspired by mountain sculpture 33

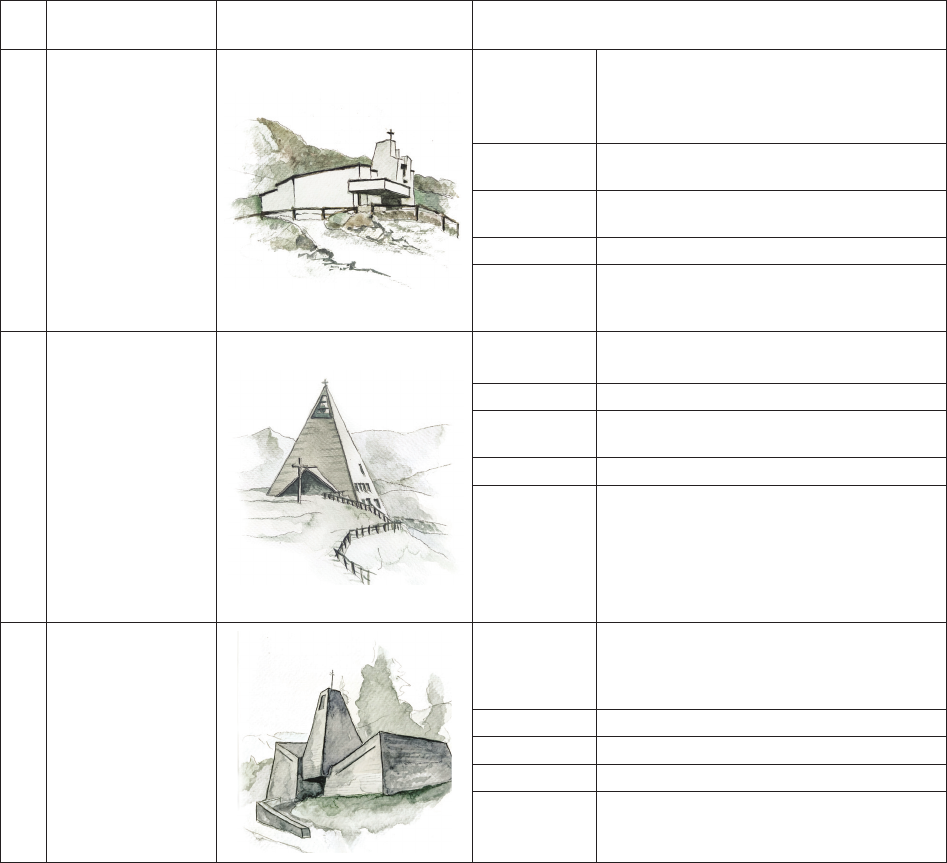

The use of dark-coloured concrete or wood (obtained

both through painting means and as a result of the natural

ageing of untreated wood) ensures that the chapels blend

into the summer landscape, when strong light brings out

individual planes, leaving some of the building lumps in

shadow. However, the same buildings stand out signi-

cantly in the winter landscape and become a strong domi-

nant feature against the bright, reective snow.

The colour of a structure can also become a carrier of

additional meanings as in the case of Mario Botta’s chap-

el. The rusty colour achieved by the corten panels refers

directly to the garnet colour, which was the main inspira-

tion in the process of creating the Granatkapelle project.

Referring to the words of Frank L. Wright, who had

a signicant inuence on the development of organic ar-

chitecture, it can be considered that the basis of architec-

ture is the character of the land where the architecture is

realised. The character of the landscape, on the other hand,

means colour, texture, “material” and greenery (Chodurska

1988). In this sense, most of the buildings analysed show

characteristics that coincide with organic architecture. The

aim of this integration is to achieve a harmonious balance

between nature and culture, and in an attempt to blend

buildings into the natural landscape, architects often use

mathematical and geometric structures (Han 2020).

It is noteworthy that the analysed buildings do not, in

principle, exhibit features of regional architecture. The

exceptions are the references at the material level, e.g.,

the use of white plastered façades, which can be interpret-

ed not only as an attempt to t the buildings in the winter

landscape or as an inuence of modernism, but as a ref-

erence to the tradition of plastering religious buildings.

Wood is also a local material used in construction. Most

chapel authors, however, seek a more “austere” means of

expression that goes beyond the material characteristic of

the “forest line” and try to draw inspiration from the land-

scape located higher up, whose image is more austere,

stony and majestic.

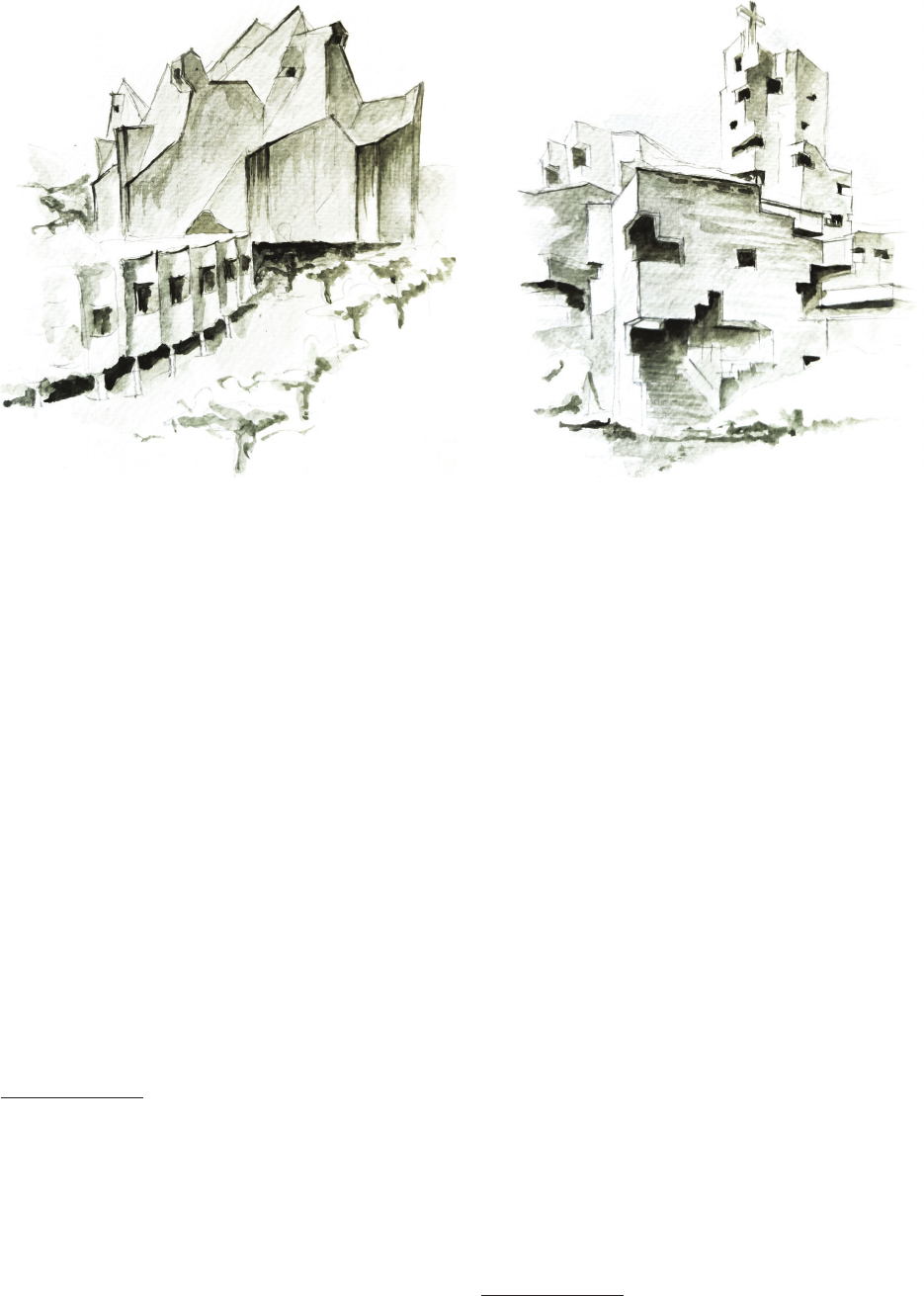

The buildings analysed reect the relationship between

human spirituality and nature. In them, architecture be-

comes a means of expression, emphasised by the spiritual

element of art. Indeed, most of these structures are per-

ceived as spatial sculptures with a signicant emotional

and aesthetic charge. Shapes, lines, proportions, materials

and textures serve to create a space of the sacred. Geomet-

ric order or the dynamism of forms are two facets of the

same quest to capture the sacred in the architectural lump.

In all the buildings analysed, the authors attempt to cap-

ture the essence of the mountain along with the symbolic

qualities ascribed to it and to create a place of contact be-

tween man and the innite.

Translated by

Adriana Cieślak-Arkuszewska,

Justyna Cichosz-Fornalczyk

References

Agkathidis, Asterios. “Implementing biomorphic design. Design methods

in undergraduate architectural education.” In Complexity & Sim plicity

– Proceedings of the 34

th

International Conference on Edu cation and

Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, vol. 1

(August 2016): 24–26.

Allen, Stan. “Geological form: towards a vital materialism in architecture.”

In Landform building: Architecture’s new terrain, edited by Stan Al-

len, and Marc McQuade, 10–17. Baden: Lars Müller Publishers, 2011.

Amouroux, David. “Rénover Prieuré, Lanslebourg (Savoie).” Archi 20–21.

Intervenir sur l’architecture du XX

e

. Accessed May 15, 2024. https://

www.archi20-21.fr/edices/prieure/descriptif-operation/.

Astakhova, Elena. “Architectural symbolism in tradition and moderni-

ty.” In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering

913, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/913/3/032024.

Banasik-Petri, Katarzyna. “Architektura a natura. Wprowadzenie.” Pań-

stwo i Społeczeństwo 19, no. 3 (2019): 5–9. https://doi.org/10.34697/

2451-0858-pis-2019-3-000.

Benyus, Janine. Biomimicry: Innovation inspired by nature. New York:

HarperCollins Publishers, 1997.

Bernbaum, Edwin. Sacred mountains of the world. Washington: Cam -

bridge University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108873307.

Chodurska, Danuta. “F.L. Wright i A. Aalto – wielcy humaniści architek-

tury.” Rocznik Naukowo-Dydaktyczny 117, (1988): 63–69.

Eliade, Mircea. Sacrum, mit, historia. Wybór esejów. Warszawa: Pań-

stwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 2017.

Eyüce, Emine Özen. “Allure of the crystal: myths and metaphors in

architectural morphogenesis.” International Journal of Architec-

tu ral Research 10, no. 1 (March 2016): 131–142. https://doi.org/

10.26687/archnet-ijar.v10i1.908.

Geva, Anat. “Symbolism and myth of mountains, stone, and light as ex-

pressed in sacred architecture.” In Architecture, culture and spiritu-

ality, edited by Thomas Barrie, Julio Bermudez, and Phillip James

Tabb, 110–111. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Gnatiuk, Liliia. “Mysticism and symbolism in sacral space.” In Interna-

tional Conference – dening the architectural space – the myths of

architecture, vol. 2 (2021): 41–54, https://doi.org/10.23817/2021.

defarch.2-4.

Granatkapelle. “The architect Mario Botta.” Accessed April 5, 2024.

https://granatkapelle.com/en/the-chapel/architect-mario-botta.html.

Greuel, Gert-Martin. “Crystals and mathematics – an historical outline.”

Symmetry: Culture and Science 32, no. 1 (2021): 41–57. https://doi.

org/10.26830/symmetry_2021_1_041.

Han, Yunxi. “Organic Architecture.” Journal of Engineering and Archi-

tecture 8, no. 2 (December 2020): 28–31. https://doi.org/10.15640/

jea.v8n2a5.

Hochleitner, Rupert. Minerały i kryształy. Określanie minerałów według

barwy rysy. Warszawa: Muza 1994.

Ivashko, Yulia, Olena Remizova, and Andrii Dmytrenko. “The avant-gar-

de of the 1920’s and the deconstructivism of today: the logic of

inheritance.” In International Conference – Dening the Architec-

tural Space, vol. 1 (2022): 43–56. https://doi.org/10.23817/2022.

defarch.1-5.

Jackowski, Antoni, and Izabela Sołjan. “Środowisko przyrodnicze a sa-

crum.” Peregrinus Cracoviensis 12, (2001): 29–50.

Juchniewicz, Beata. “Architektura – od obrazu natury do jej symulacji.”

Czasopismo Techniczne. Architektura 106, z. 1-A (2009): 314–318.

Kirchen-Online. “Acla / Medel – Sogn Giachen (St. Jakob d. Ä.).” Accessed

May 15, 2024. https://www.kirchen-online.org/kirchen--kapellen-in-

graubuenden-und-umgebung/acla---medel---st-jakob-d-ae.html.

Mathieu, Jon. “The sacralization of mountains in Europe during the

Modern Age.” Mountain Research and Development 26, no. 4 (No-

vem ber 2006): 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2006)

26[343:TSOMIE]2.0.CO;2.

Miller, Tyrus. “Expressionist Utopia: Bruno Taut, Glass Architecture,

and the Dissolution of Cities.” Filozofski vestnik 38, no. 1 (2017):

107–129.