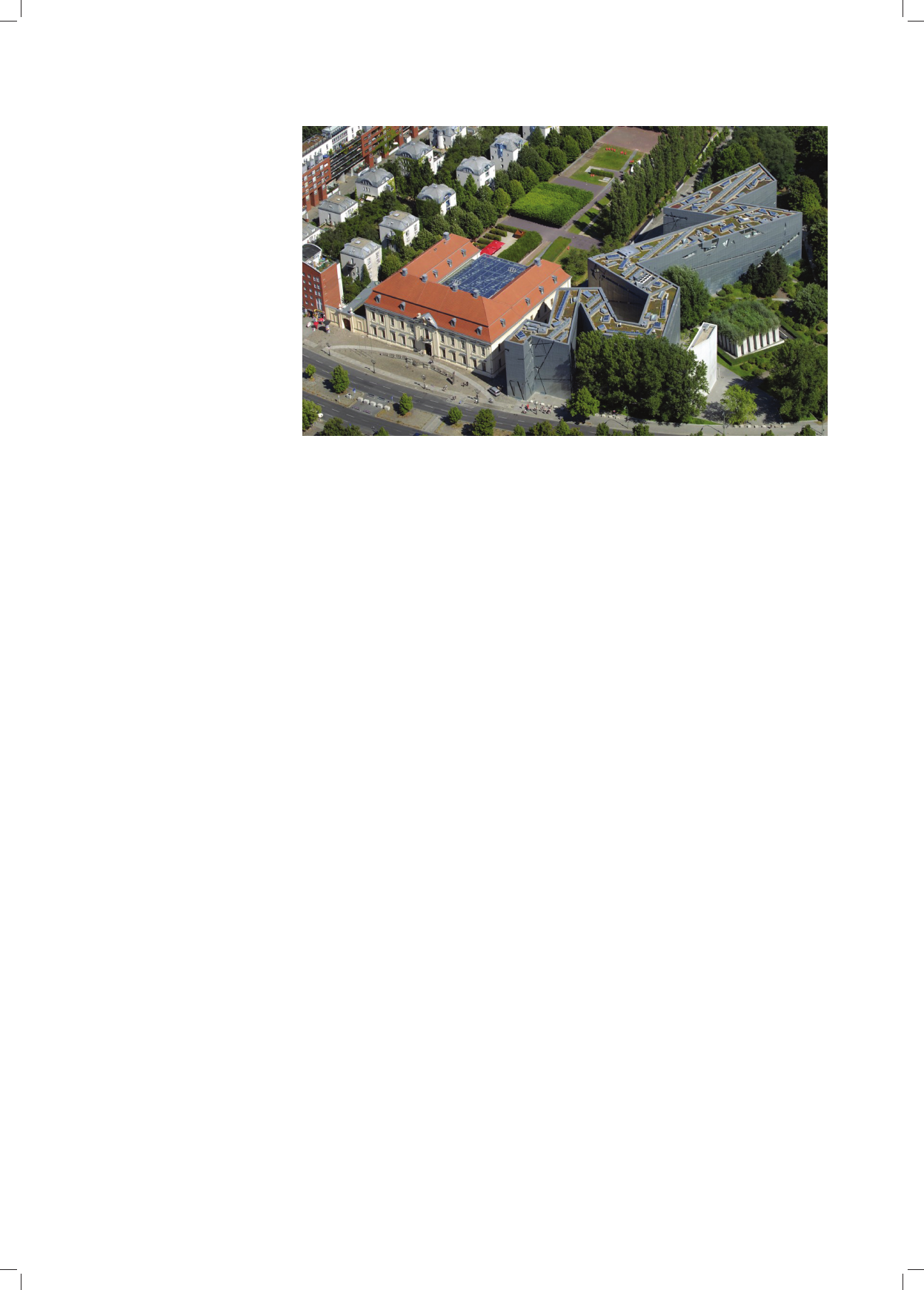

Założenia estetyczne dekonstruktywizmu/Aesthetic assumptions of deconstructivism 33

was subjected to, which is suggested by the very architec-

tural form of the museum. It is not important what is told

here, but what emotions are propagated in the visitor and

with what feelings he or she leaves the museum building.

By propagating emotions here, I mean generating the

most basic human and typically spontaneous feelings in

an artificial, almost laboratorylike fashion.

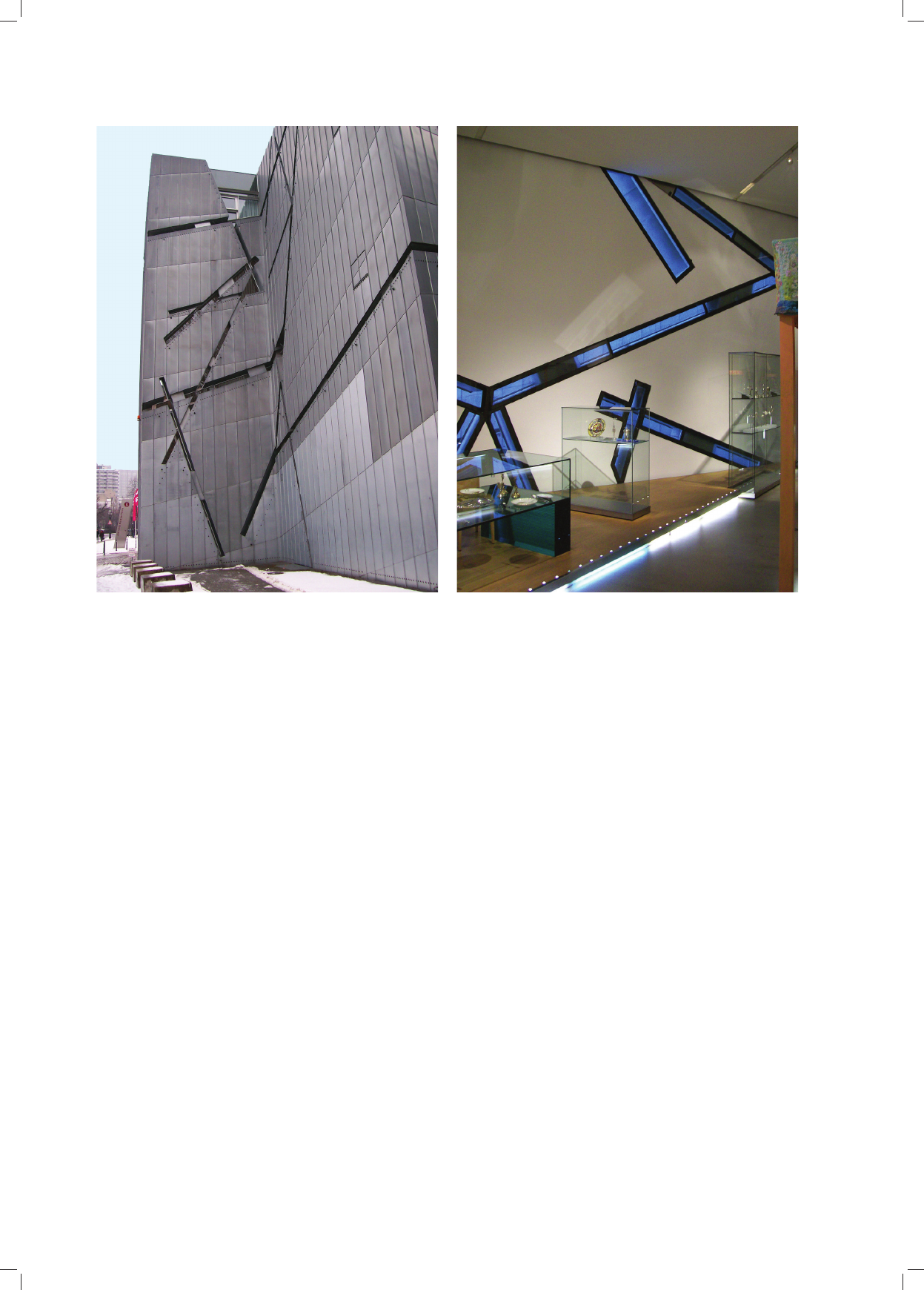

The building itself seems to carry a content, but it is

a content of an unusual type for an institution propagating

knowledge. It is passed by abstract forms, and not muse-

um exhibits. We do not see a narrative here about the fate

of the Jews, but their “representation” in architectural

form. This is a moderate form of perceptual functionalist

art – a theory explaining art which is able to transmit

knowledge not contained in logical judgements, but

through its convictions [5, p. 299]. As Gołaszewska puts

it: In a work of art, it’s about showing the world – not

passing on information about it [...] [5, p. 411]. It is quite

a perverse applying deconstructivism to such a project,

when as Kenneth Frampton notes: […] deconstructivism

is an elitist and disengaged movement [13, p. 313]. It is

an exercise for architects, a game played in open view, not

a style of public spaces, speaking out on important mat-

ters. Frampton’s words suggest that he regards decon-

structivism as an extremely autonomous movement.

Ironi cally the heteronomy of the architecture of the Jewish

Museum in Berlin is very clear. There is an obvious

dependence of the postulated aesthetics on the moral val-

ues [5, p. 470]. How often do buildings create such pow-

erful feelings and reflections of a moral nature in

their users?

The majority of public buildings are used by people of

differing sensibilities at the same time. The museum in

Berlin somewhat escapes this rule. It is more like a cine-

ma or a concert hall, where people go with a particular

expectation of a musical experience, attune themselves

and share their feelings. In such a case it is, however,

musical or cinematic sensations which have a a building

adapted to their function. The architecture itself does not

play a role in generating emotions. The powerful emo-

tions aroused by a work are very often a desirable effect

in the case of literature or painting. There is, however,

something antiarchitectural in speaking about expressive

architecture, as if being in a situation where an architect

displays his or her emotions in public [14, p. 174]. In the

case of the Berlin museum, these are impressions precise-

ly set out by the investor. Libeskind is not telling us about

his emotions, but about the emotions accompanying an

entire community. This is exceptional in the world of

architecture. It is most often encountered in monuments,

and probably only unanimously accepted there and intui-

tively sensed, regardless of the cultural circle [15, p. 154].

Monuments do not display individual feelings, but the

spirit of an entire community. They speak of the grand

events, of mass suffering and universal hopes which

accompanied people in historic moments. They allow the

individual to penetrate that which a part of humanity

experienced before them. Emotionalist theories of art,

especially the expressionist theory of Eugène Véron, reject

evaluating art through the criterion of beauty in favour of

miotowość (quasisujet) dzieła sztuki to określenie ukute

przez Mikela Dufrenne’a, który twierdzi, że dzieło sztu-

ki nie tylko jest wyposażone przez autora w jakości, ale

samo ma zdolność ich wyrażania [5, s. 44]. Analizowane

tu muzeum z pewnością jest bardzo żywym nośnikiem

jakości treściowych. Sądzę, że po wyjściu z muzeum nie-

wiele osób jest w stanie przytoczyć jakąś datę bądź miej-

sce związane z eksponatami wystawianymi w muzeum.

Moim zdaniem jest za to niewątpliwie poruszony cierpie-

niem i tułaczką, jaką musiał przebyć naród żydowski, co

sugeruje sama forma architektoniczna muzeum. Nie jest

ważne, co jest tu opowiadane, ale jakie emocje są prepa-

rowane w odwiedzającym, z jakim poczuciem opuści on

gmach muzeum. Poprzez preparowanie emocji rozumiem

tu wytwarzanie tego najbardziej ludzkiego i zazwyczaj

spontanicznego uczucia w sposób sztuczny, zbliżony do

laboratoryjnego.

Budynek sam zdaje się nieść treść, ale jest to treść nie-

spotykanego, dla instytucji szerzącej wiedzę, rodzaju. Prze-

kazywana wszechobecnymi abstrakcyjnymi formami, a nie

eksponatami muzealnymi. Nie spotykamy się tu z „narra-

cją” o losach Żydów, ale ich „reprezentacją” w formach

architektonicznych. Jest to umiarkowany funkcjo

nalizm

poznawczy sztuki – teoria opowiadająca się za sztuką mo-

gącą przekazać nie wiedzę zawartą w sądach logicznych,

ale przekonania [5, s. 299]. Jak uważa Gołaszewska:

W dziele sztuki chodzi o pokazanie świata – a nie o prze-

kazanie informacji o nim [...] [5, s. 411]. Jest dosyć prze-

wrotne zastosowanie kierunku dekonstruktywistycznego

do takiego projektu, gdyż jak zauważa Kenneth Framp-

ton: […] dekonstruktywizm jest elitarystycznym i nieza-

angażowanym nurtem [13, s. 313]. Jest ćwiczeniem dla ar-

chitektów, zabawą w oczach ludzi, a nie stylem przestrzeni

publicznej mogącym zabierać głos w istotnych sprawach.

Wypowiedź Framptona sugeruje, że uznaje on dekonstruk-

tywizm za nurt mocno autonomiczny. Jak na ironię hete-

ronomiczność architektury Muzeum Żydowskiego w Ber-

linie jest bardzo wyraźna. Jest tu oczywista zależność

postulatywna strony estetycznej od wartości moralnej [5,

s. 470]. Czy budynki często kreują wśród użytkowników

tak silne uczucia oraz przemyślenia natury moralnej?

Z większości budynków publicznych korzystają jed-

nocześnie ludzie o zróżnicowanym samopoczuciu. Mu-

zeum w Berlinie trochę wymyka się takiej klasykacji.

Bliżej mu do kina albo lharmonii, do których ludzie

idą z konkretnym nastawieniem na obiecujące przeży-

cie muzyczne, nastrajają się i dzielą odczucie wspólnie.

W tym przypadku jest to jednak odczucie muzyczne czy

lmowe, które ma przystosowany do swojej funkcji bu-

dynek. Sama architektura nie ma tu pełnić funkcji „emo-

cjotwórczej”. Silne emocje wywoływane przez dzieło są

bardzo często pożądanym efektem w przypadku literatury

czy malarstwa. Jest jednak coś antyarchitektonicznego

w mówieniu o ekspresji architektury jako o sytuacji, gdy

architekt przekazuje swoje uczucia publiczności [14, s.

174]. W przypadku berlińskiego muzeum są to dokład-

nie zdeniowane przez inwestora wrażenia. Libeskind

nie opowiada nam o swoich uczuciach, ale o uczuciach

towarzyszących całej społeczności. To wyjątek w świe-

cie architektury. Najczęściej spotykany w przypadku