58 Wojciech Niebrzydowski, Agnieszka Duniewicz

2010, 32). However, the result of such a work methodology

is an untrue, fragmentary image of architecture, devoid of

the multidimensionality, spatiality and materiality inherent

in this art. As Juhani Pallasmaa notes, the real image of an

architectural work, consistent with the physical truth, can-

not be discovered otherwise than through touch (Pallasmaa

2005; 2013). This sense most fully perceives the structure

and material properties of solids, but also shapes partic-

ularly intense mental and spiritual equivalents accompa-

nying the experience of architecture (Kłopotowska 2020;

2021; Kurek, Maliszewski 2009; Łebkowska, Wróblewski

and Badysiak 2016). Unfortunately, issues related to de-

sign and haptic perception are not suciently researched

and popularized in architectural theory. Despite the emerg-

ing voices of researchers calling for the appreciation of the

sense of touch as an indispensable and even leading aes-

thetic language, unwavering, radical ocularcentrism still

dominates in contemporary architectural research.

The consistent distance with which architecture-science

approaches the issues of haptics seems surprising when

compared to the ennoblement this sense has received in

philosophy. The following should be mentioned here: the

concept of touch, subordinate to the intellect, formulated

by Aristotle (Arystoteles 1972); the medieval denial of the

sinful sense; the progressive thought of René Descartes

combining tactile sensations with other senses and noticing

the phenomenon of synesthesia (Descartes 2002); recog-

nition of the existence of common elements between sight

and touch by George Berkeley (Struzik 2009); the mental

concept of Pierre Maine de Biran, linking tactile experi-

ences with the resistance of things (Tisserand 1949); the

promotion of touch in the hierarchy of the senses created

by Johan Gottfried Herder (“I feel myself! I am!”) (Herder

1973), sealed by the 19

th

and 20

th

century philosophers of

touch, such as Edmund Husserl (Husserl 1974), José Ortega

y Gasset (Ortega y Gasset 1982), Emmanuel Lévinas (Lévi-

nas 1998), Maurice Merleau-Ponty (Merleau-Ponty 2001).

Due to the very weak basis of haptic issues in the the-

ory of architecture, the great interest in the sense of touch

among contemporary architects seems to be an interest-

ing phenomenon. The works of Zvi Hecker, Glenn Mur-

cutt, Peter Zumthor, Steven Holl, Kengo Kuma, Krystyna

Różyska-Tołłoczko, Dariusz Kozłowski, Tomasz Mańkow-

ski take the form of almost a tribute to touch and convey

a clear message that we should return to the corporeality of

perceiving architecture, which was a natural, intuitive start-

ing point for the rst builders (Stec 2015).

Tadao Ando’s

work also shows that the sense of touch is as important in

architecture as the sense of sight. He states that he always

uses natural materials in those parts of buildings that come

into contact with the human hand or foot because he is

convinced that people become aware of the true quality

of architecture through the body (Botond 1990, 125). In

his buildings, Ando brings people into direct contact with

the texture of concrete. This happens especially in entrance

areas, where narrow passages between monolithic walls

force the person to touch the material. In his projects, rail-

ings, seats and oors full similar tasks.

The gap between theory and reality identied by the au-

thors is well commented by Michał Podgórski: Ocularcentric

blindness does not allow us to notice the fact that hap tic

aesthetics is the dominant aesthetics. It has been used to

dene modernity, progressiveness, worldliness, luxury and

auence for over a hundred years (Podgórski 2011, 9). In

this situation, the authors considered it justied to address

the issue of haptics and its importance in the creation of

architectural forms.

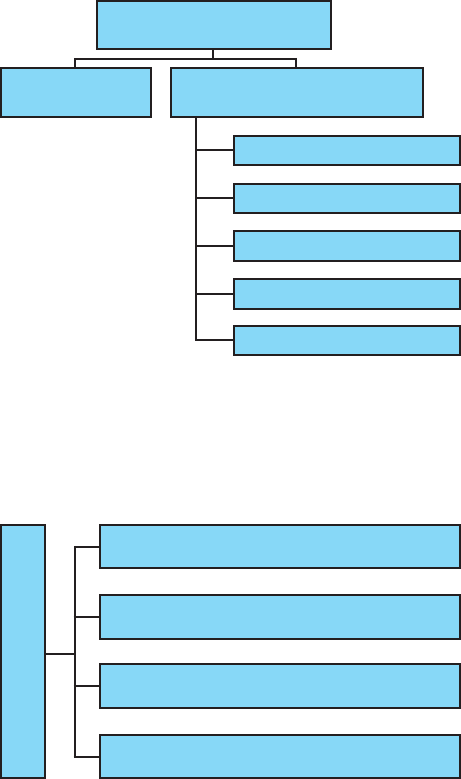

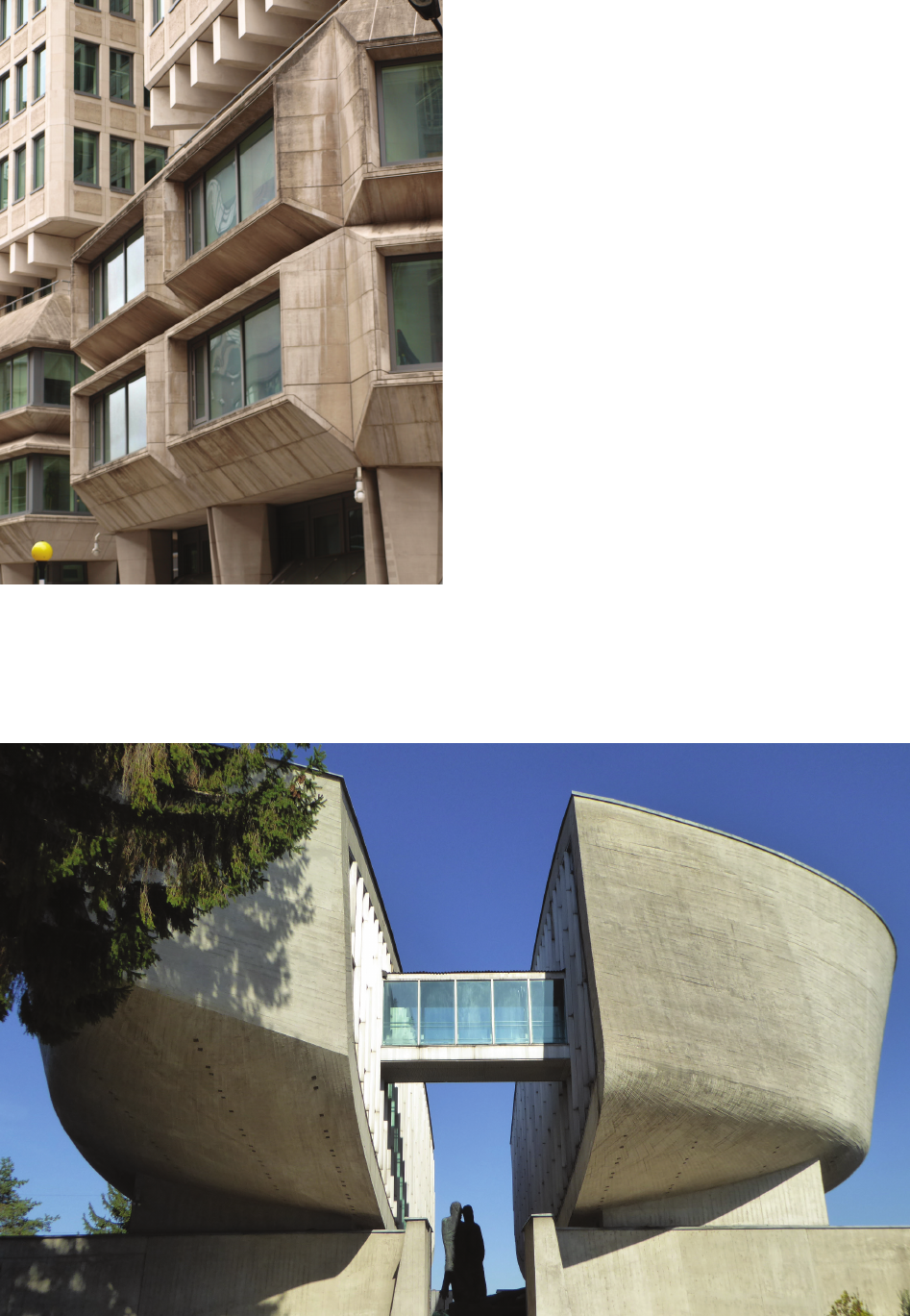

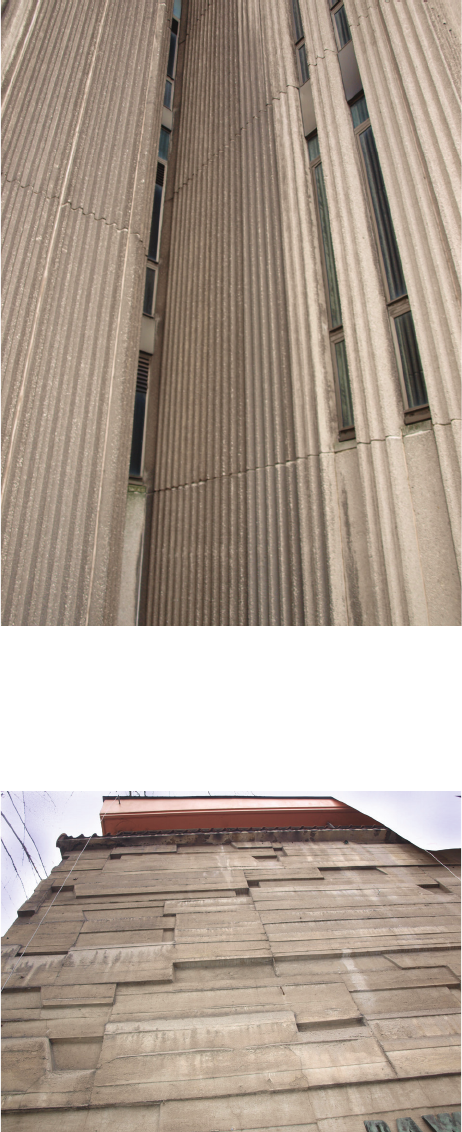

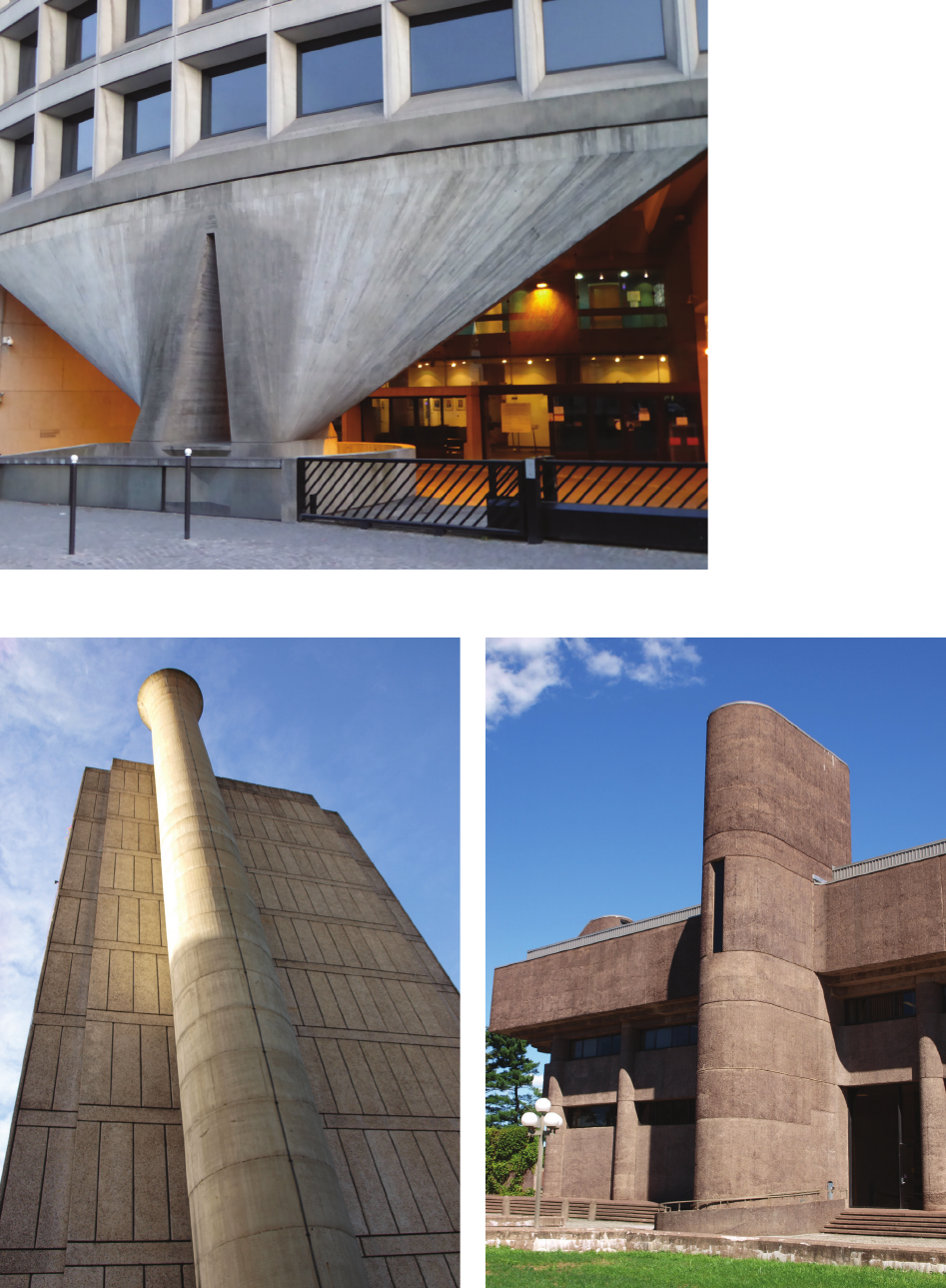

The trend that the authors researched is brutalism. It

developed from the end of World War II until the end of

the 1970s (Niebrzydowski 2018). Haptic threads can be

seen both in the theory of brutalist architecture and in most

brutalist buildings. Brutalism placed great emphasis on the

issue of architectural form. Contrasting combinations of

solids, strong articulation of elements and dynamics of the

composition inuenced human senses and emotions. The

rough and expressive textures of raw materials encouraged

people to explore the buildings by touch.

The issue of haptics as an important component of the

aesthetics of brutalist works has not yet been the subject

of comprehensive, focused studies on brutalism, hence the

author’s team decided to subject this aspect, overlooked

by other researchers, to a detailed research analysis. The

main goal of the research is to discover, name and scien-

tically organize the elements of haptic aesthetics present

in the works of brutalist architecture. This article attempts

to build a scientic apparatus enabling the observation and

assessment of haptic aesthetics – analogous to commonly

recognized methods that refer only to visual perception.

However, in the longer term, by popularizing the results

of both parts of the research, the authors aim to draw the

attention of contemporary scientists to the need to question

the dominant ocularcentric perspective to appreciate the

role of touch in architectural experiences.

Materials and methods

The presented study is a continuation and complement

to the rst part of the research devoted to the identication

of pro-haptic threads in the theory of brutalist architecture

(Niebrzydowski, Duniewicz 2024). The research conduct-

ed so far has indicated a strong (though not directly articu-

lated) element of haptic thought, visible in such aspects as:

– negation of the doctrine of modernism,

–

architectural and non-architectural inspirations of bru -

talists,

– innovative architectural experiments,

– main ideas.

The results of the analyses from the rst part became

the starting point for the authors for research devoted to

the identication of haptic elements in completed brutalist

works. This duality of research is justied by Jacek Krenz,

who states that only in the workshop phase of the creative

process does the idea materialize based on the art of build-

ing. Then decisions are also made regarding the selection

of materials, textures, colours, etc. (Krenz 2010, 35, 36).

He also adds that it depends on the professional skills of

the architect whether […] the transposition of the idea into

a spatial shape will make the form become a carrier of

the intentional meanings assumed at the beginning (Krenz

2010, 36).