14 Hanna Grzeszczuk-Brendel

aspects of dealing with green-blue infrastructure, also in

the historical context, was discussed in Standardy utrzy-

mania terenów zieleni w miastach [Maintenance standards

of green spaces in cities] [7]. The aforementioned publica-

tions also provide an extensive bibliography on the subject.

Methods

The discussed examples, taken from in situ and archival

research as well as from the subject literature, concern var-

ious types of green spaces in Poznań from the turn of the

20

th

century and are based on the reforms of that time

2

. They

focused on improving the existing urban environment by

developing new relationships between green spaces and ar-

chitecture, creating an integral aesthetic, semantic and func-

tional whole. The growing importance of urban greenery is

a byproduct of social changes in the 19

th

century, mainly the

improvement of urban hygiene and the democratization of

society, which included broadened access to greenery.

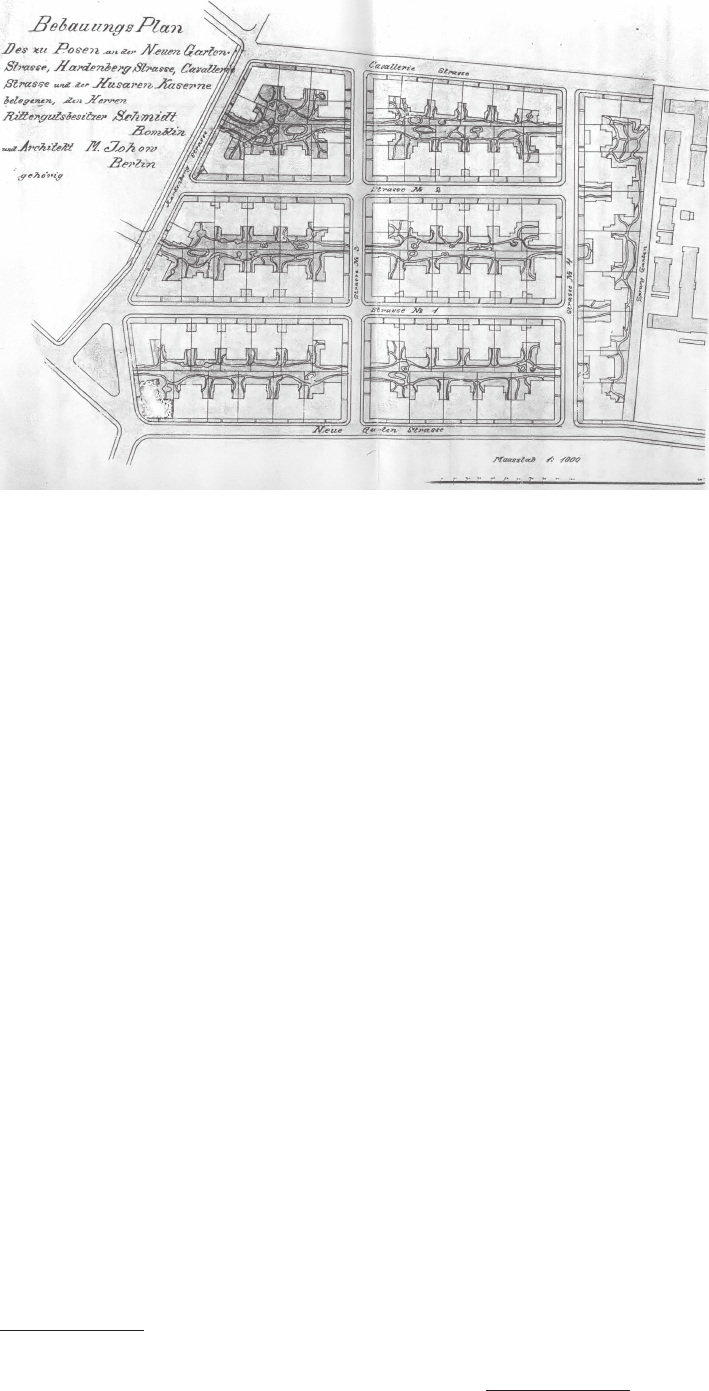

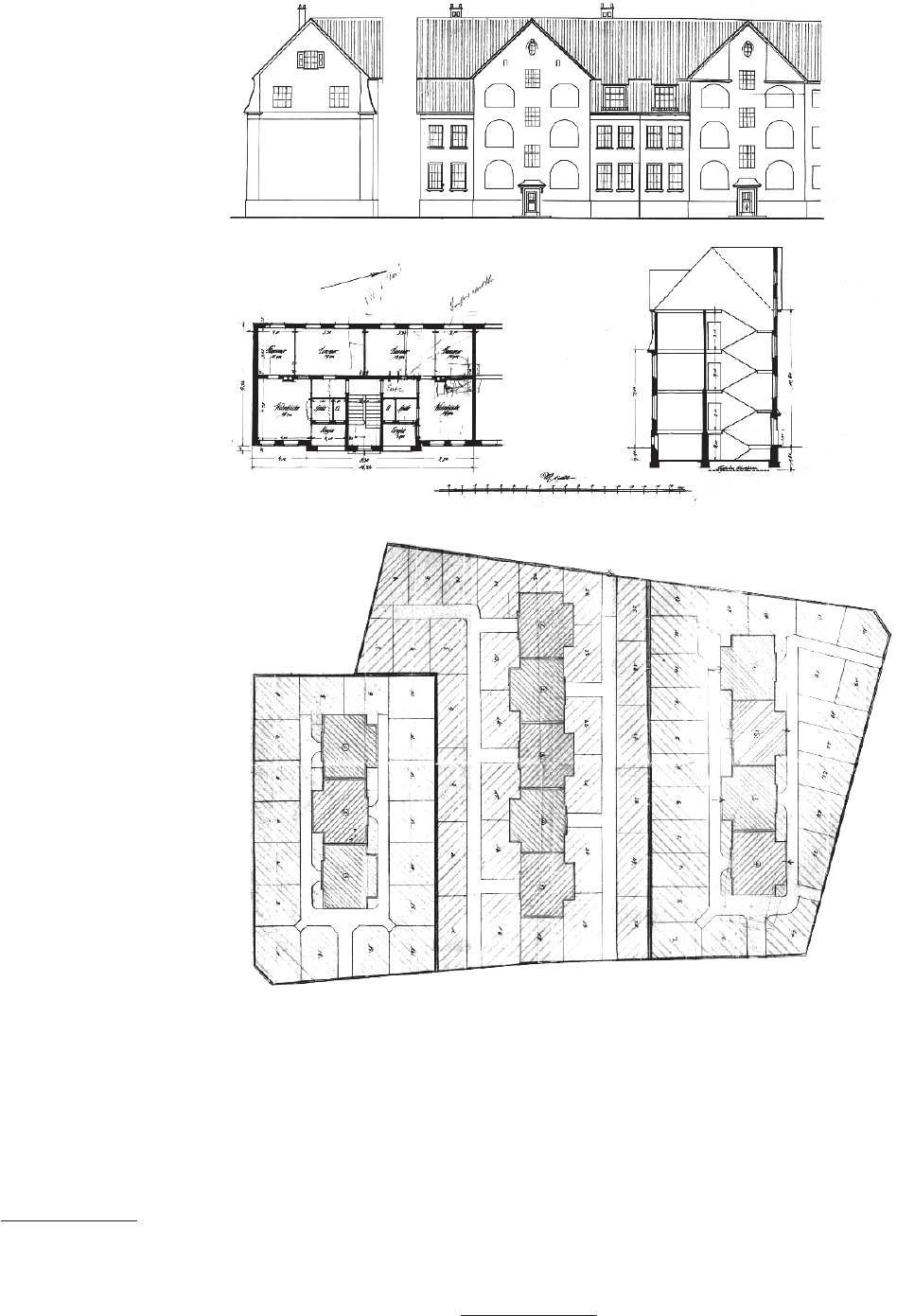

Reform ideas were introduced in urban expansion proj-

ects of the city, but the most interesting of those ideas con-

cerned greenery in the immediate surroundings of the build-

ings, which in turn inuenced the building oor plans

3

.

Introducing new forms of urban green spaces

Reform activities were prompted mainly by the patho-

logies prevalent in 19

th

-century metropolises, which, as

a result of rapid urbanization, began to experience the

ne gative eects of excessive population growth and high

density housing, which, in turn, led to cyclical epidem-

ics and social unrest. Around the mid-19

th

century, when

modern water supply networks and sewage systems were

introduced, special attention was paid to green infrastruc-

ture and its role in improving living conditions in the me-

tropolis. For example, in Paris, large-scale work was un-

dertaken to reduce high-density housing and shape green

spaces in the city. The main idea behind Haussmann’s plan

from 1852 was to introduce broad boulevards lined with

rows of trees. They ensured ecient communication

4

, im-

proved ventilation, puried the air and beautied the city.

There was a signicant change in thinking about the role of

greenery – aesthetics was supplemented with a primarily

hygienic function, and consequently green areas became

increasingly important, as they regulated the urban eco-

system and improved the broadly understood well-being

of residents.

Changes in the character of urban greenery also reect

the democratization of 19

th

-century society. Until the 17

th

century, only the privileged upper classes were granted ac-

2

During the interwar period, reform ideas were continued in Poznań

by the wedge-ring system of greenery, which was used by Władysław

Czarnecki to tie together the topography of the terrain with the historical

ring system [5], [8], [9].

3

This is why proposals calling for a departure from the idea of

a metropolis, such as Ebenezer Howard’s garden cities, were never in-

cluded. See: [10].

4

This facilitated the movement of the army and the police in quell-

ing riots.

cess to greenery in cities: the gardens of aristocratic fam-

ilies were a symbol of prestige, an open-air living room

next to the palace. Although the rst public parks appeared

at the end of the 17

th

century, it was not until the turn of

the 19

th

century that they appeared in larger numbers, also

as a result of opening up private gardens to the public (see:

[11]–[13]). The democratization of “green luxury” is evi-

denced not only in the establishment of parks, such as the

Bois de Boulogne and the even more proletarian Bois de

Vincennes in Paris, but also in raising the prestige of grand

avenues, such as the Champs-Élysées

5

in Paris, Unter den

Linden in Berlin, and Wilhelmstrasse (currently Marcin-

kowskiego St.) in Poznań.

Integration of greenery and architecture:

reform activities in Poznań

at the turn of the 20

th

century

Home to a highly vocal community striving to improve

living conditions in the city, Poznań at the turn of the 20

th

century was considered an example of multilateral think-

ing about how green areas should be treated as an inte-

gral component of urban and housing reforms. New and

unconventional solutions were put forth to improve urban

hygiene, shape social interactions, and enrich the symbolic

meanings of urban space.

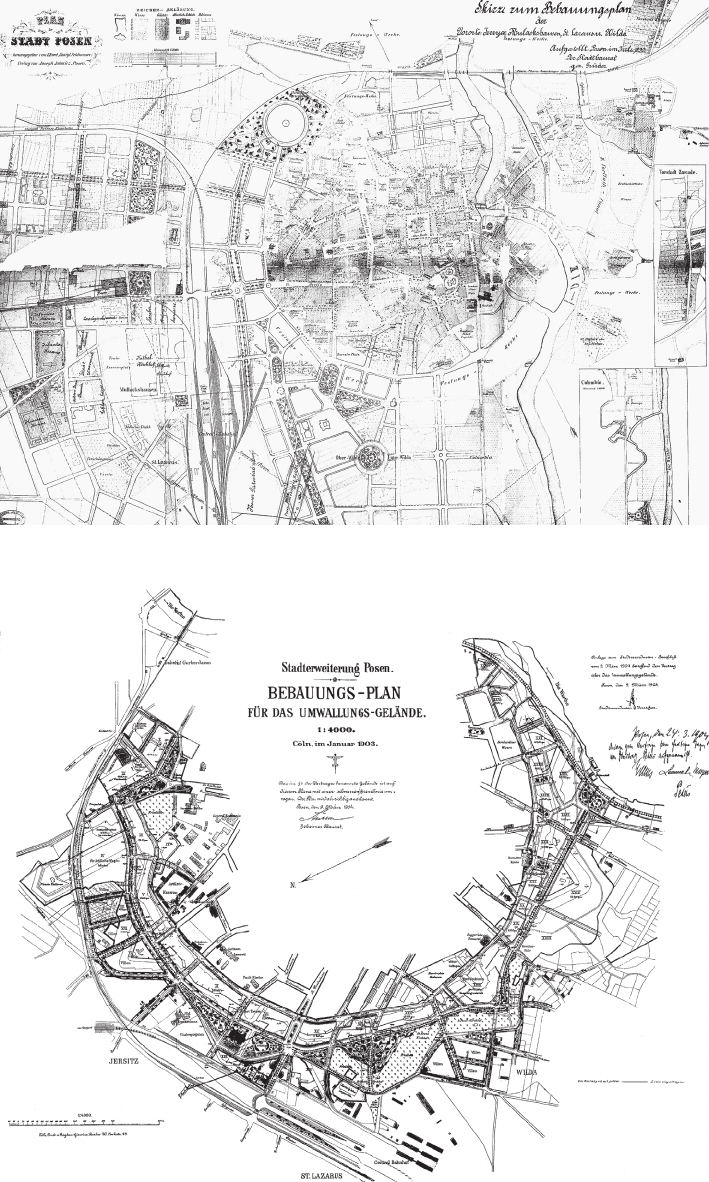

Surrounded by a ring of fortications

6

, 19

th

-century Poz -

nań was marked by high density of buildings and a paucity

of

green areas. Private gardens were disappearing, and de-

spite many eorts, due to lack of space and the high cost of

land, no public park, an integral element of the 19

th

-cen-

tury European city, was created in Poznań [17, p. 417]. As

a result, the only major green area in the city was to be

found on Wilhelmstrasse (currently Marcinkowskiego Ave-

nue), which runs alongside Wilhelmplatz (currently Wol-

ności Square). These were the most magnicent elements

of David Gilly’s plan to expand Poznań after the incorpora-

tion of Greater Poland into the Prussian partition

7

.

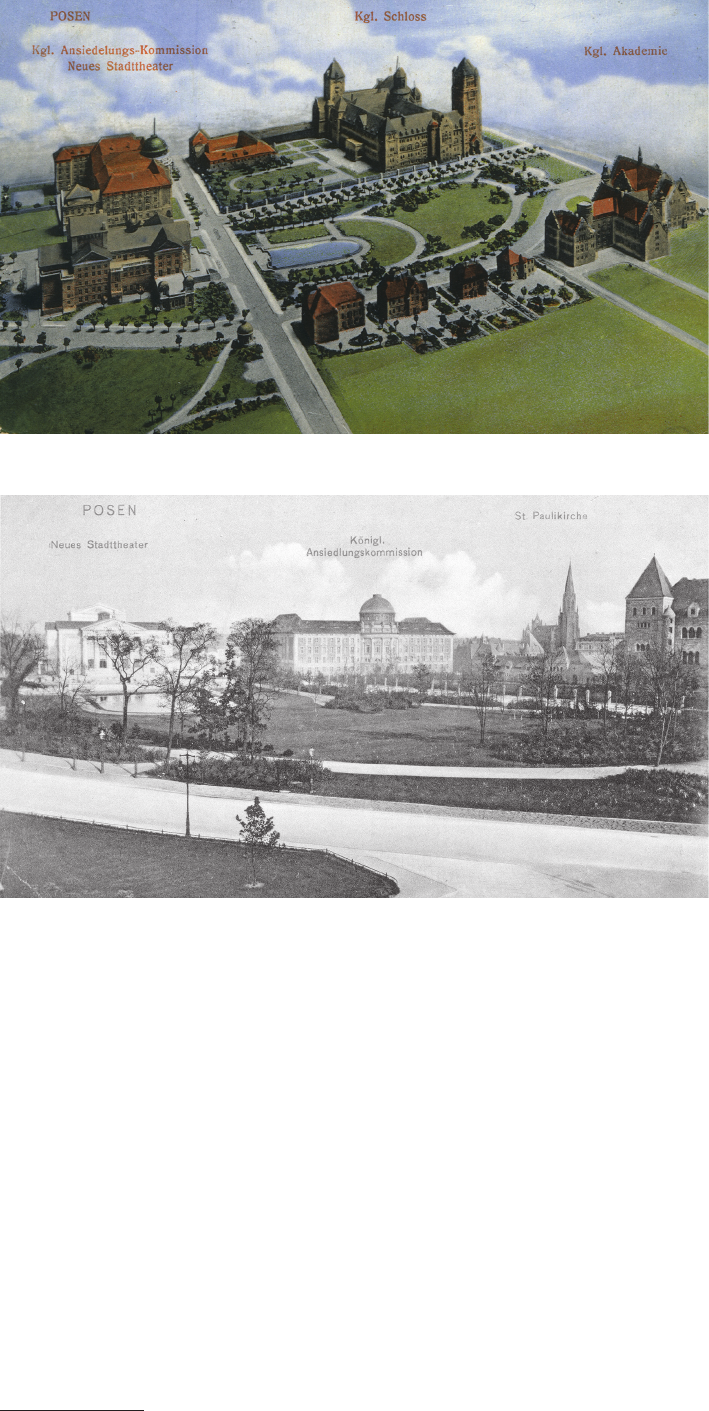

Broad avenues, streets and squares densely lined with

trees [18, p. 9] gave the new site, which was intended for

military marches and parades, a more civilian character of-

fering a place for strolls – the greenery softened Poznań’s

image as a Prussian garrison city (Fig. 1). Wilhelmplatz,

transformed in the 1870s into a square with a picturesque

composition of trees and bushes (see: [19]), took on the

role, along with Wilhelmstrasse, of the city’s living room.

This only free public space saw a specic accumulation of

functions: from strolls to state ceremonies related to, for

example, the unveiling of monuments asserting the pres-

ence of Prussia

8

(Fig. 2).

5

Cf. [14]. On the role of the Champs-Élysées and the use of green

spaces in 19

th

-century Paris see [15]. See also: [16].

6

Built in 1828–1869.

7

Research by Ostrowska-Kębłowska had attributed authourship of

this plan to David Gilly; this nding has been recently put in question by

Andreas Billert, who claims that the architect is Christian Friedrich Gün-

ther von Goeckingk and Otto Carl Friedrich baron von Voss [17], [18].

8

In 1870 a monument designed by Cäsar Stenzel was erected at

Wilhelmplatz, which commemorated the Battle of Nachod. In 1889

in Wilhelmstrasse a monument designed by Robert Baerwald of Wil-