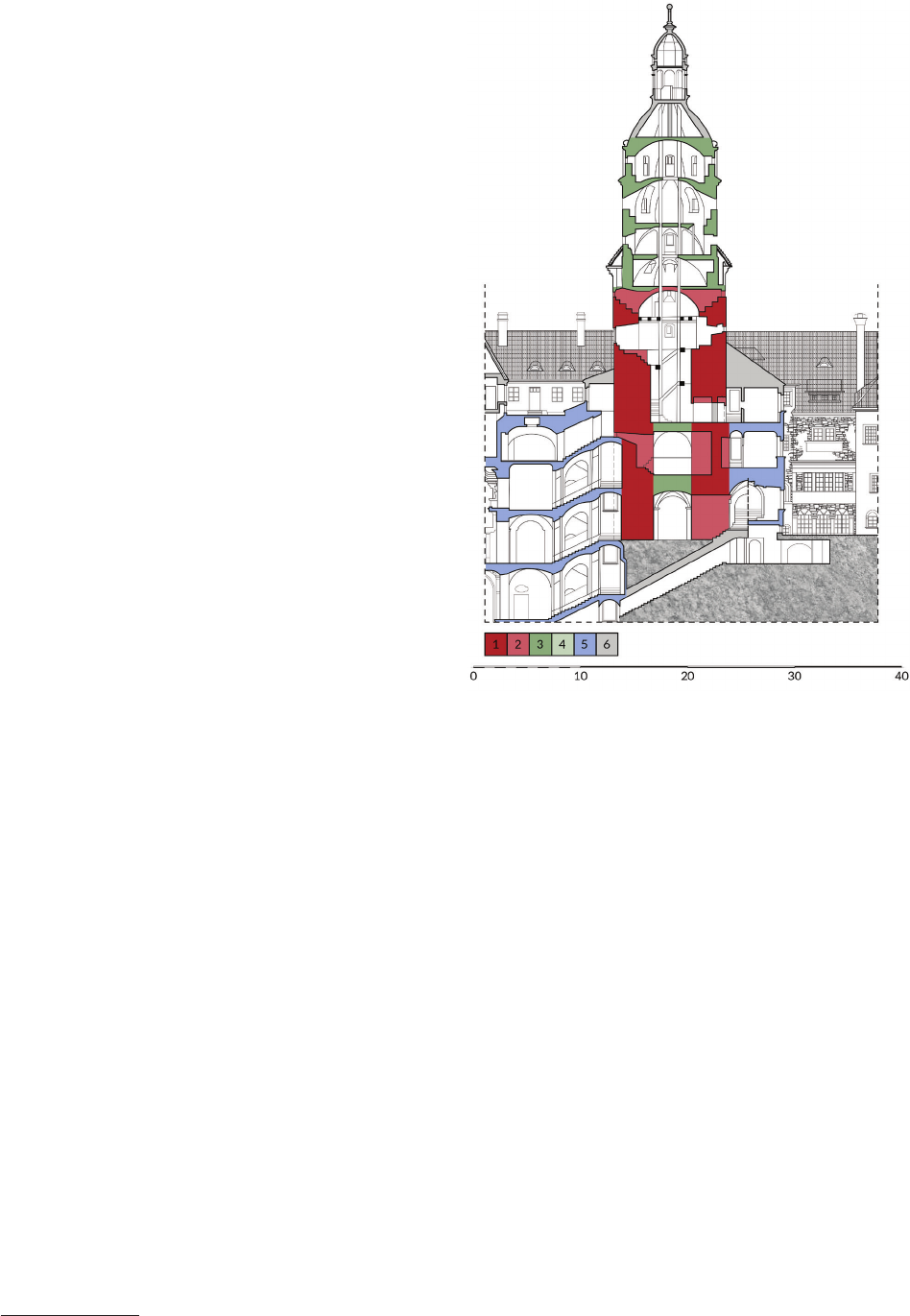

8 Małgorzata Chorowska, Roland Mruczek

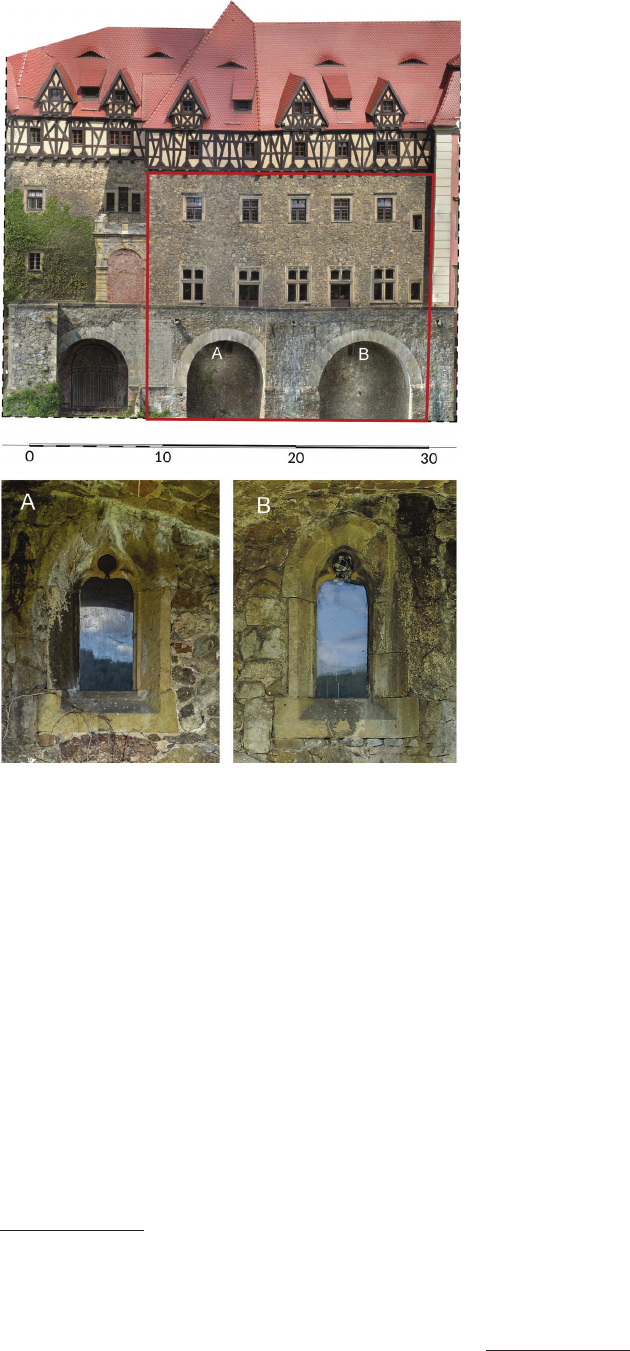

This is evidenced by the way in which the three cellar win-

dow openings were built, of which only the splayed lin-

tels and, in one case, a fragment of the splayed reveal has

survived. They were certainly primary and not secondarily

pierced, which means that they were planned and executed

already during the construction of the perimeter wall. The

gable wall enclosing this wing to the east at basement level

is medieval, constructed of stone and attached to the ram-

part

3

. The stone outer face of this wall shows consistently

applied levelling layers extending upwards to the level of

the ceiling above the present 3

rd

storey, the original 1

st

oor

of the north wing. Obviously, this wall is punctuated by the

Renaissance and Baroque window openings. The lack of

medieval windows, apart from the cellar windows

4

, is to be

explained by the fact that this was the exterior elevation of

the castle (Fig. 6) exposed to military action and, in addi-

tion, the north elevation, so the large openings were prob-

ably on the courtyard side. The small medieval windows

may have disappeared when they were replaced by younger

and larger ones. Experience suggests that such actions were

the norm. A noticeable modern intervention in the structure

of the north wing’s façade was an oriel window with a win-

dow and the date “1580”, as well as three windows in fas-

cia stone frames with identical proles to the oriel window.

Two of them, located to the east of the bay window, illumi-

nated the four-arched staircase built into the north wing at

the time. With regard to the lack of traces of the medieval

toilet oriels, which are generally found on the northern ele-

vations of the residential wings, it can be hypothesised that,

as in the castle in Jawor, they were replaced by more con-

venient latrine towers. The photogrammetric image of this

elevation shows, more or less in the middle, the remains of

some kind of masonry stone structure, which would have

corresponded in dimensions to these types of towers. This

structure must have been demolished before the reconstruc-

tion of the north wing in 1580.

On the subject of the castle cellars under the north wing,

it should be recalled that they lled in the hollow between

the two rock culminations, the east and west. The west-

ern culmination is still preserved very high today. At its

highest point, it reaches to the level of the ceiling above

the mezzanine oor, between the contemporary 2

nd

and 3

rd

storeys. Translating this into the realities of the 13

th

to 14

th

century, we can say that it protruded by about 2.0 m above

the level of the courtyard at that time

5

. The north wing was

3

In the case of the stone walls, the jointing at the corners was car-

ried out by means of so-called stirrups extending from the previously

masoned wall every 1.0–2.0 m. No such stirrups were observed on the

section of the corner of the north wing available for study, but the mortar

joints in the defensive wall and the gable wall of the north house were

similar to each other and unstained with soil. Earth staining would have

to have occurred if the construction of the defensive wall and cellars had

been staggered over a longer period of time.

4

Thick stone sills were inserted into the cellar windows in the 20

th

century, probably as part of the 1909–1923 reconstruction. During the

Nazi reconstruction of 1943, combined with the demolition of the cra-

dle vault of the main eastern cellar, the window recesses and reveals

disappeared.

5

The same situation is encountered at Grodno Castle, where the

high cli, at the end of the castle opposite the entrance, reaches the level

of the 1

st

oor.

its surface, sloping down and forming irregular shelves

and kinks. It is possible that the presence of the gap was

the result of the external eld stairs that were left in place

in the 17

th

century to provide communication between the

upper castle and the terraces established on the west side

of the castle. This stair, estimated to be 1.5–2.0 m wide,

connected the upper level of the 16

th

-century castle kitchen

(at mezzanine level between the present oors 2 and 3) and

the medieval cellar under the north wing. Both the kitchen

and the staircase can be seen in many engravings showing

the castle from the west.

Formercellarsunderthenorthwing

Research into the cellars under the northern wing of-

fered the best chance of explaining the medieval building

history of the castle. In the 1960s, these cellars were identi-

ed as Renaissance, which disturbed the proper view of the

origins of Książ for many years, as it focused researchers’

attention exclusively on the south wing with its trefoil win-

dows in the arcades. The thesis of the 16

th

-century origins

of the north wing seemed to be in line with the meaning

of the references to the oldest documented building work

carried out on the castle between 1548 and 1555, which

was linked to it, and with elevations in the “Renaissance

style” (Zivier 1909, 12).

Meanwhile, an analysis of the cellars under the northern

wing and the northern section of the defensive wall shows

that these investments were carried out at a similar time.

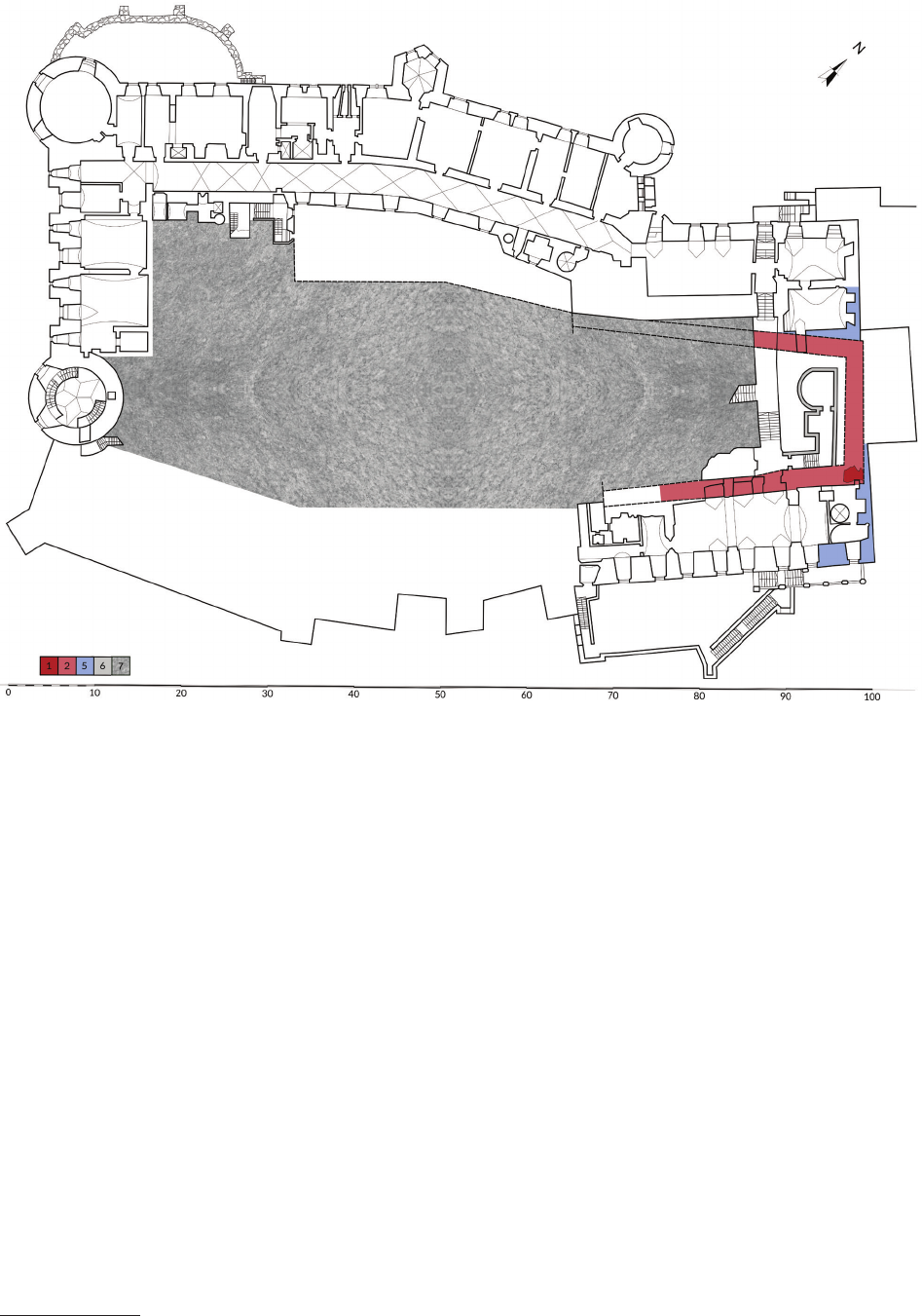

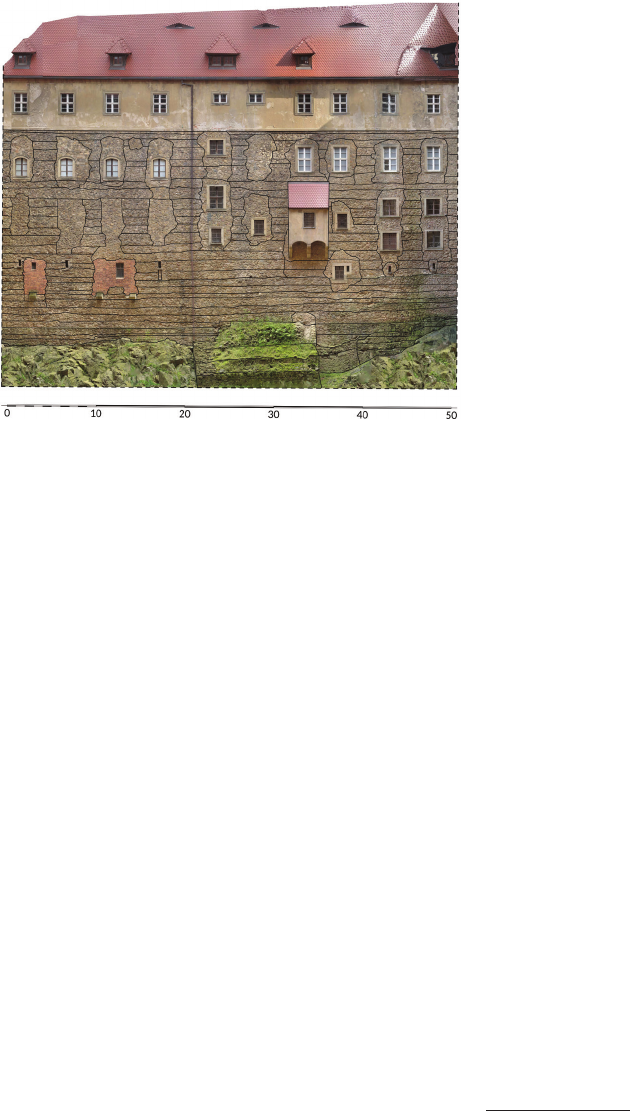

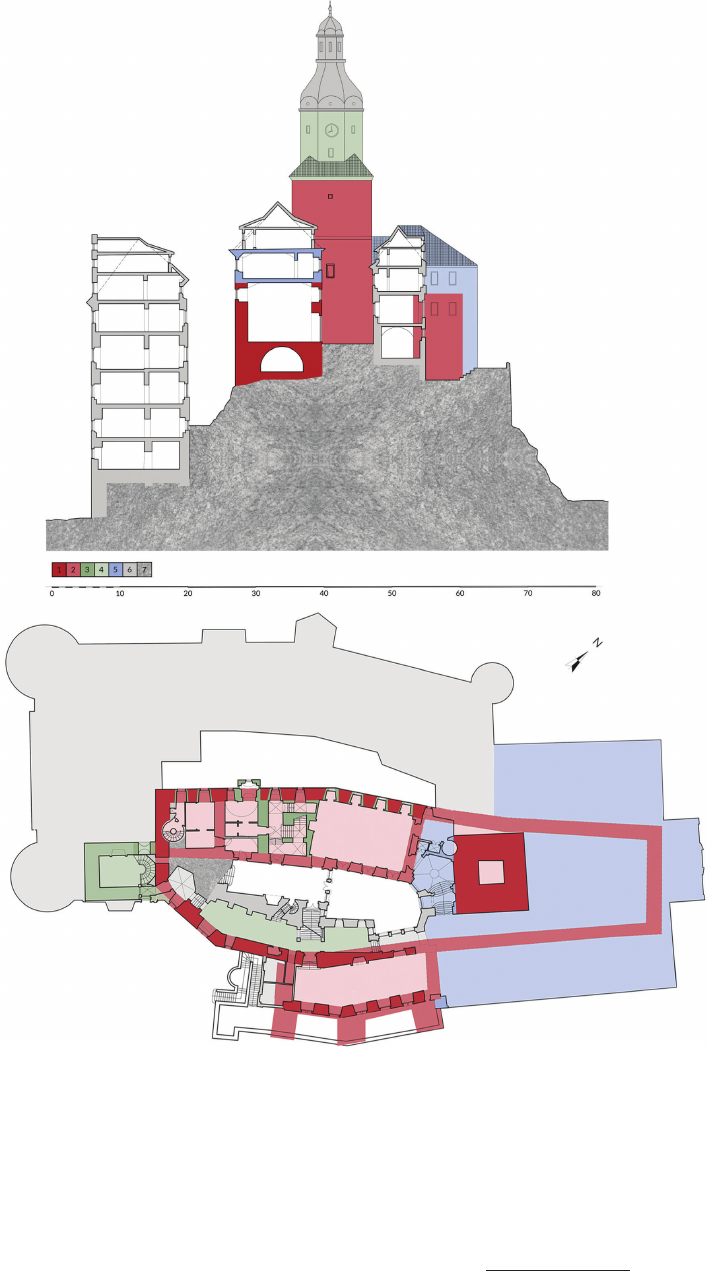

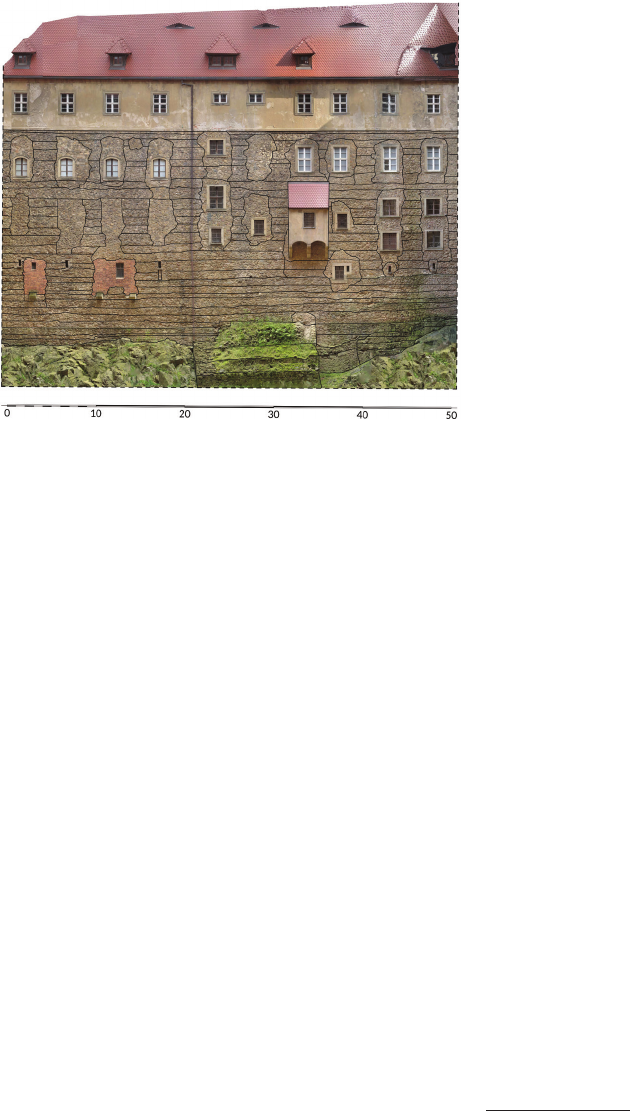

Fig. 6. Książ Castle. Photogrammetry of the elevation of the north house

in the upper castle, as seen from the north courtyard.

The elevation is marked with levelling layers, which show the extent

to which the medieval parts of the perimeter wall have been preserved

(elaborated by M. Bogdała, M. Noszczyk,

source: Chorowska et al. 2023, 14)

Il. 6. Zamek Książ. Fotogrametria elewacji domu północnego

na górnym zamku, widziana od strony dziedzińca północnego.

Na elewacji zaznaczono warstwy wyrównawcze, które pokazują

zakres zachowania średniowiecznych partii muru obwodowego

(oprac. M. Bogdała, M. Noszczyk,

źródło: Chorowska et al. 2023, 14)