72 Sandro Parrinello, Francesca Picchio, Silvia La Placa

ied. This takes place through a dual synergy: the drawing

as an experience, and thus as memory, and the drawing as

a document, which constitutes memory about a narrative.

Reproducing an artwork requires establishing a multi -

tude of dialogues, with the work, with the author of the

work, with the space in which the work is experienced,

and with the user of the work. Drawing a work, then, goes

beyond the simple concept of reproduction, of copying.

Drawing, by its own denition, allows for an interpretation,

simplication of forms, or even transformation of mean-

ings to create, from a work, something “other”.

This contribution aims to describe some drawing activ-

ities conducted on an extremely rened artwork explain-

ing, in addition to the methodological components that de-

ned the actions and activities conducted, the relationship

between the artwork, its copy and its digital copy.

This is a path of knowledge based on drawing, in which

an approach to material and physical knowledge of the

artwork is developed through an analysis of forms and

through processes of measurement [5].

It is therefore a comparative process, more cultural than

strictly dimensional, of recognizing morphometric quali-

ties in relation to measurement units.

The drawing reproduction does not seek to be a sterile

copy, coming from a communication between the drawer

and the artwork. The drawer seeks to weave a dialogue

with the work to elaborate a sign.

The drawing intends to humbly contribute to a specic

analysis, enhancing the forms that characterise the gures

and the decorations drawn. Drawing sets graphic limits

that segmented the continuous nature of the reality.

If a digital drawing represents an artwork, it is relevant

to take into account two aspects for a methodological in-

terpretation. It is necessary to evaluate the more complete

cultural and historical framework in which the drawing is

formed, considering also the goals and the purpose of the

digital activities, and also the nature of the digital draw-

ing, that could be considered as a database

5

[6].

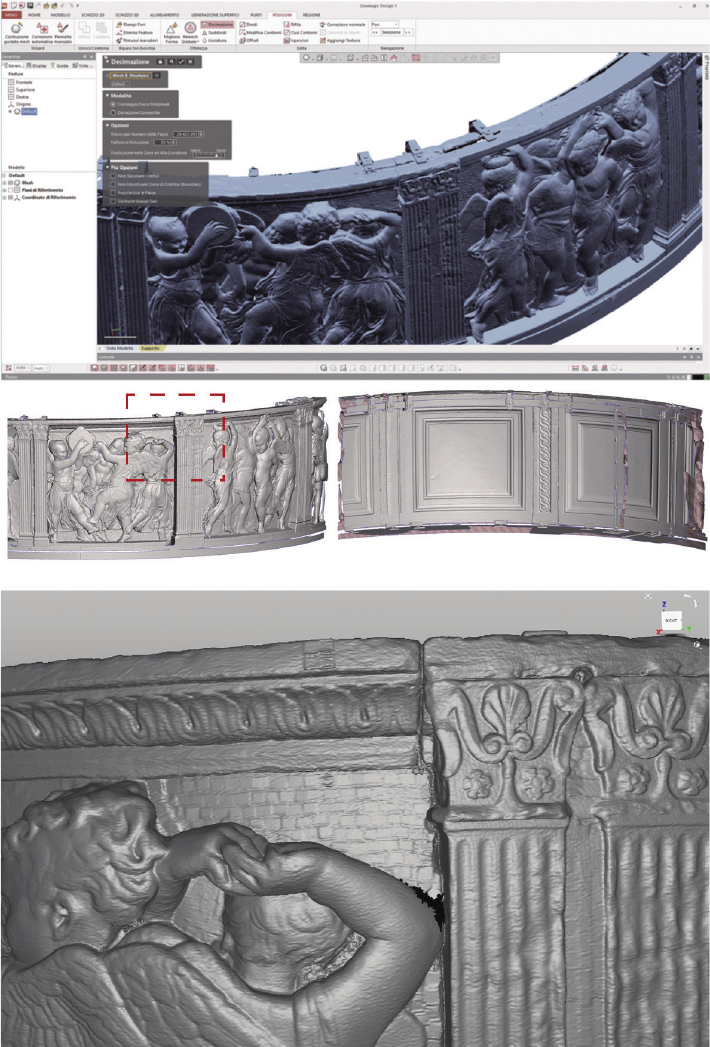

It is evident that a documentation procedure can only

establish and constitute databases of dierent natures that

dialogue themselves. Based on comparative and analyti-

cal activities, the process is aimed at reproducing forms,

proportions and models in a digital language, creating les

that can be interconnected through several softwares [7].

This is why the process of creating a cognitive database

on Cultural Heritage is a fundamental step to the deni-

tion of a memorisation of the built heritage [8].

Comparative practices between digital and real are

rarely dened through linear continuity. A recursive log-

ical-temporal development constitutes the dialogue. This

is composed by recall, re-proposition, remembrance or re-

ection, rapid analogy, etc. [9].

The communication meaning is mixed with the mean-

ings of knowledge and data archiving. This meaning con-

5

A 2D or 3D drawing, a critical interpretation of the complexity

of reality, contains a series of coded information in the form of spatial

coordinates or alphanumeric codes that, appropriately selected and orga-

nised, enrich the descriptive potential of the real object, amplifying its

communicative message.

cerns how a certain form of knowledge and archiving

could or should be represented. In digital methods and

tools there are limits concerning the representation. These

limitations of a representation, that being symbolic, also

bring limits to the fundamental notion of meaning.

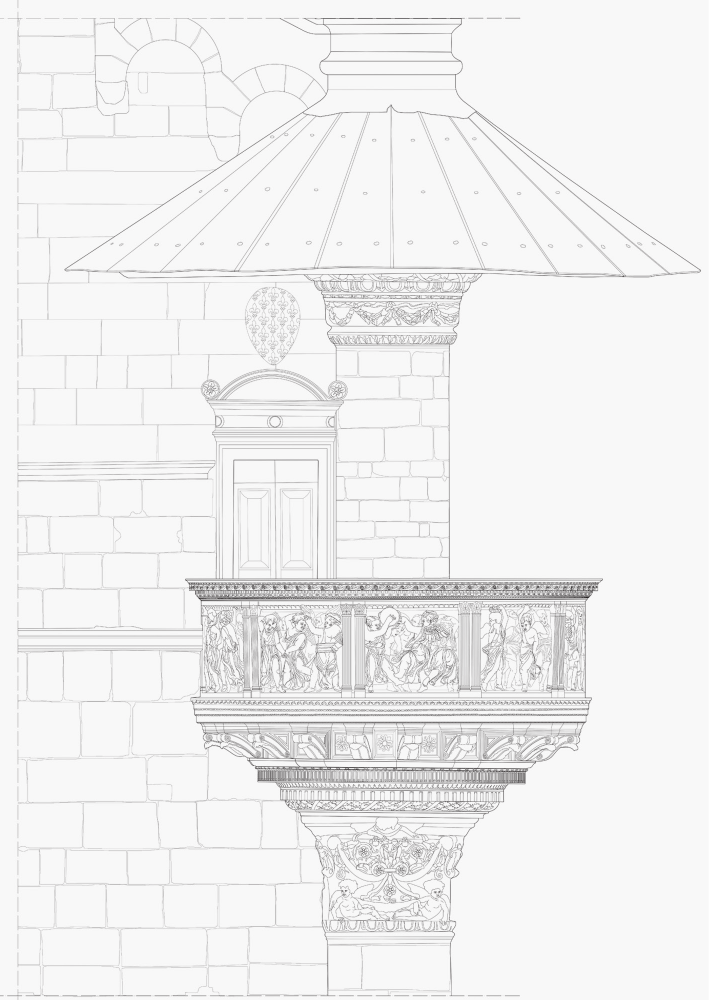

Through the architectural digital surveying it is possi-

ble to obtain reliable models, in terms of metric data, that

duplicate the environment under investigation. From these

duplicates it becomes possible to develop multiple studies

and analyses, digital simulation to control the develop-

ment of the place predicting activities of design, monitor-

ing, restoration or enhancement [10].

Often instrumental reliability is made to coincide with

me trical accuracy to simplied reproduction of shapes from

real measures. This topic, which does not work in the sci-

ence of architectural representation, could be applied to

have a simplistic qualication of digital models.

Every instant of the modelling process is characterised

by a tension that concerns the approximation of the form,

the denition of the limit. This tension originates a paradox

that is established in the relationship between the precision

of the data, which contemplates the presence of an error,

the denition of a numerical value that qualies a shape

and the adherence between the digital and the real model.

Discretisation, selection and systematisation of the

amount of digital data acquired are procedures aimed at

simplication of the digital model [11]. This simplica-

tion of forms gives the digital model a simplicity to the

advantage of its interconnectivity that makes it an aid to

have precise knowledge because, in some way, it is in-

complete. The notion of completeness concerns the inn-

itesimal limit of imperfection that therefore qualies the

digital model.

The production of technical models, digital and physical

products, is the focus of this research that emphasizes the

practical and applied aspects of digital documentation of

Cultural Heritage. In particular, the focus concerns com-

munication, memorisation, comparison, and knowledge of

digital products, through a series of references and recur-

rences based on the nature of the dierent models obtained.

The allegorical model,

“the invention and the Sacra Cintola narration”

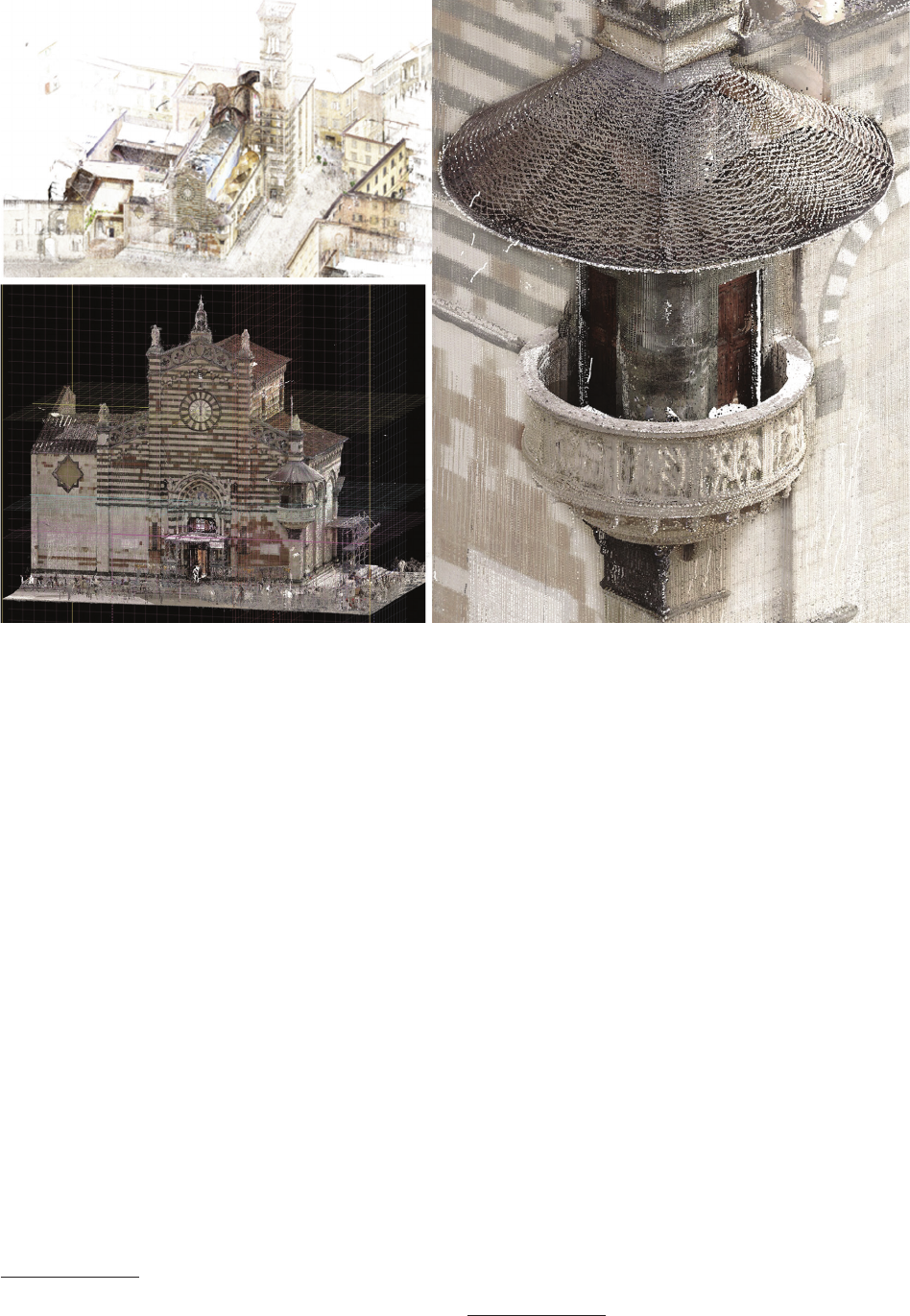

Donatello’s pulpit in Prato constitutes an allegorical

system in relation with Santo Stefano’s Cathedral. It com-

municates the events connected to the city and its relic,

the Sacra Cintola (or Sacred Belt), placed by the apos-

tles around the Virgin’s waist before her assumption into

heaven. The Belt arrived in Prato in 1141, thanks to Mi-

chele Dagomari, a noble from Prato who went to Jeru-

salem on the occasion of the First Crusade (1096–1099).

Dagomari left the relic as a gift to the Pieve di Santo Ste-

fano. The Pieve became an important religious site for

devotees because of the preservation of the Belt [12]. In

the early 1300s the church was enlarged and, in 1428,

the pulpit was built at the intersection of the south and

west elevations of the Cathedral, in a position that ensures

its full visibility from the two squares. Donatello’s pulpit

represents the last stage of the Ostension ritual and from