114 Tomasz Konior

an important condition in the design, one which may be-

come a sort of asylum and a source of tranquility. He also

recalls that inspirations with shapes, which were created

by nature, are constantly present in design and architec-

ture [6]. A conrmation of these words can be the two

examples found below.

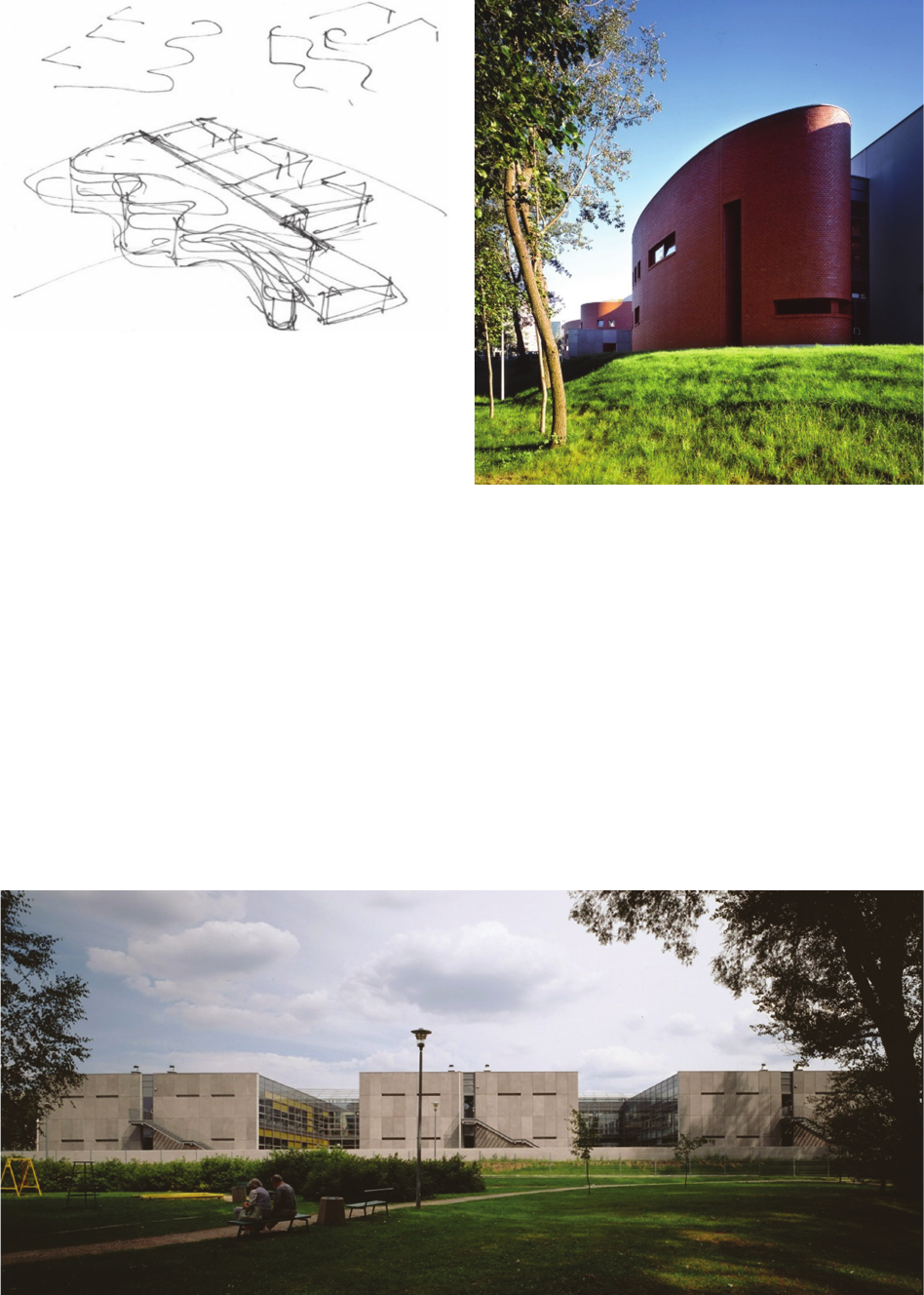

The Białołęka Middle School and Culture Center

in Warsaw, 2005

Architecture: Tomasz Konior, Tomasz Danielec, Konior

Studio

Function: school, a culture center with a theatre hall

and a library, local sports facility

Floor space: 7713 m

2

Design: 2000–2002

Completion: 2005

The Białołęka Middle School and Culture Center is

a complex of buildings, which has four independent func-

tions: a school, a library, a culture center with a theatre,

and a sports facility. The design idea of the structure is

most fully expressed by the term used by the author: im-

mersed in the landscape along the Vistula River (Fig. 1).

The buildings which are a part of a valuable stand of his-

toric trees make up a sort of enclave of culture and nature.

The soft line of the brick wall which merges the individu-

al bodies into one from the side of the entrance is a clear

(Fig. 2). At the same time, it is an easy to remember ele

ment

of architecture. The curvilinearity of the winding wall is

a reference to the Vistula riverbanks, while at the same

time being a distinguishing feature, which expresses the

idea of the architect to incorporate a part of the landscape

along the Vistula into the area of the school park (Fig. 3).

The second, internal part of the brick wall, creates

a covered forum, also setting out space that combines the

independently functioning facilities, i.e., a school for 800

students, a culture center with an auditorium for 400 peo-

ple, and a public library.

The 70-meter long, winding wall plays the role of the

element consolidating various functions. At the same time,

it allows for the use of the covered, elongated space for

everyday spontaneous meetings, but also ocial events,

important for the life of the school and the local commu-

nity. The feature which accentuates the space of the great

hall is the oval auditorium hall which seems to be an au-

tonomous element of the structure. It is a distinguishable

form, visible in the shape of the building.

The educational part is housed in three segments placed

parallel to one another. The longer walls of the building

are glazed to keep a view of the patios. The end walls

made out of large concrete prefabricates, have small win-

dow openings. The narrow, horizontal glazings let in the

western light into distant classrooms. Concrete, glass, and

brick are the dominant materials in the nishing, eleva-

tions and interior of the building.

The whole of the arrangements (layout) shows two

formally distinct ways of shaping architecture. The spac-

es situated at the intersection with the curvilinearity of

the brick wall establish a soft relationship with it and

are reected in the adjacent interiors. Buildings that are

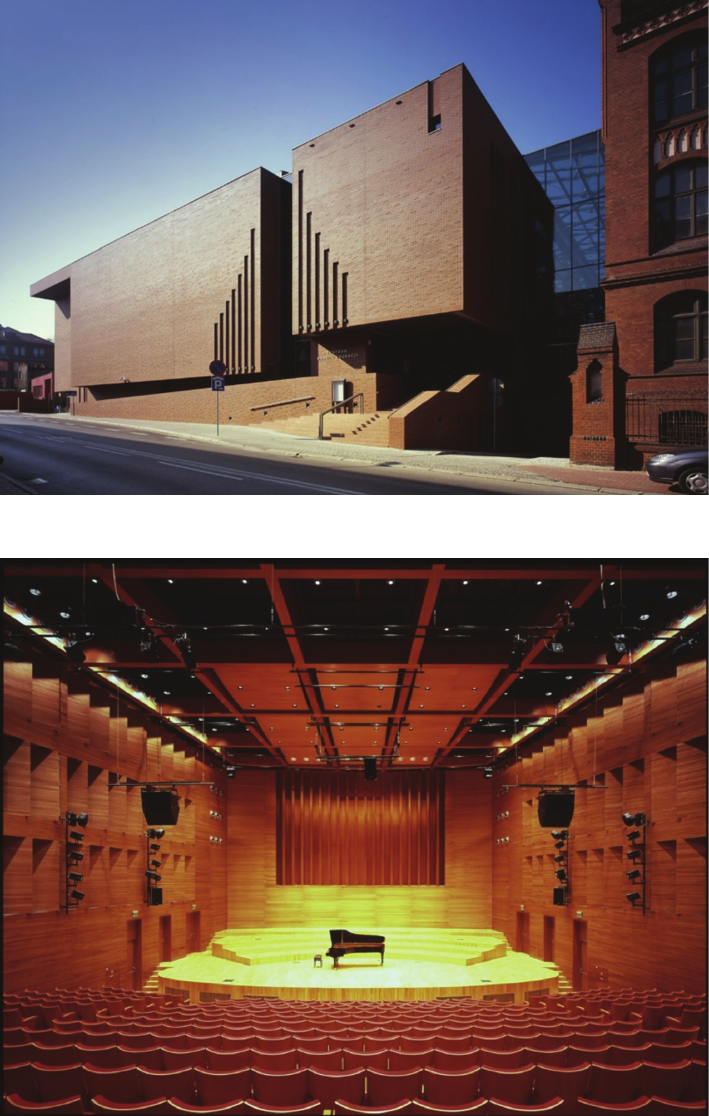

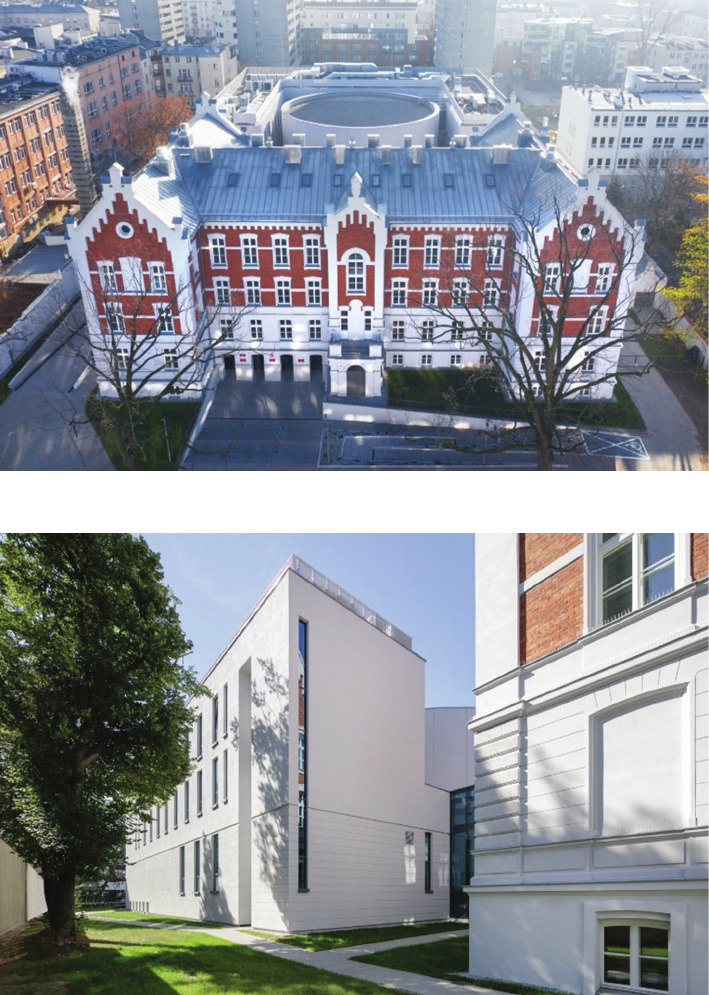

(The Białołęka Middle School and Cultural Center in War-

saw and the head oce of Press Glass in Konopiska near

Częstochowa), as well as facilities located in the urban struc-

ture (the “Symfonia” Building of the Academy of Music in

Katowice and the State Music School Complex in Warsaw).

Context of location and context of architecture

The reections on the shaping of a building in relation

to its surroundings should be started by recalling yet an-

other contemporary architect Bernard Tschumi, who in his

multi-volume work Event Cities [5] says that a building al-

ways exists in specic surroundings; in a geographic location

or a historically, culturally, or economically dened context.

The architectural concept, dening the ultimate form

and materiality of the designed building may have vari-

ous connections with the context, while the architect does

not have to take into account all the local conditions. In

emphasizing the signicance of the context, Tschumi in-

troduces three relations into the discussion, ones that are

possible in relations between the concept of the designed

building and the context expressed historically or contem-

porarily dened through pre-existing surroundings. He

denes it in the following way:

– indierence, meaning the independence of the con-

cept from the context,

– reciprocity, when the concept of the new facility and

the spatial context supplement each other, or when the

planned building is an architectural response to existing

buildings,

– conict between the existing surroundings and the

newly designed structures, which generally leads to the

possibility of changing the context by the structure [5].

The relations of the architectural concept to the context,

in allowing for the simultaneous consideration of the loca-

tional and cultural context, make it possible for the archi-

tect to choose various approaches to the relations between

the spatial and cultural context of the place. Inspirations

with the culture of the city or place are visible through the

use of materials related to the history and local tradition.

A similar approach deals with inspirations with forms

connected with culture understood in a somewhat wider

although still local sense. The form in the planned design

may be processed by the designer, however, its connection

with tradition should be clear and understandable.

The architect, who decides to distance himself from lo-

cal traditions, usually designs a facility that formally ex-

presses negation and/or conict with the context in place.

From time to time, new, formally dierent architecture

may become an impulse that will inuence spatial chang-

es in the surroundings – as a result altering the current,

existing context [5].

Architecture in the context of natural landscape

In his book Ecstatic Architecture [6, p. 20 .], Charles

Jencks points to nature as an inseparable element of the en-

vironment connected with human civilization, and further

underlines its signicance, claiming that it is more import-

ant than culture. Open to new interpretations, it becomes