80 Karol Czajka-Giełdon, Krystyna Kirschke

the instrument

10

. The bid for the work was submitted by

two students from the Electromechanical Faculty, Edward

Popiel and Marian Śliwiński. The cost estimate included:

a full cleaning of the organ and pipes, setting up the con-

necting pipes, gluing together some of the wind chests for

the pedal voices, repairing the punctured front pipes, turn-

ing on the “Vox humana” voice, tuning the 28 voices, clean-

ing the organ console, keyboard and inspecting the motor.

The entire work was expected to cost 35,000 PLN. The

missing pipes were to be made at the University’s expense.

In December, Vice-Rector Kazi mierz Zipser contacted the

Central Executive Committee of the Polish Socialist Party

asking for funding to repair the organ

11

. The repair process

ended on 22 March 1948 with the acceptance of the com-

pleted work

12

. It is important to mention that there was also

another political theme emerging here, which increased the

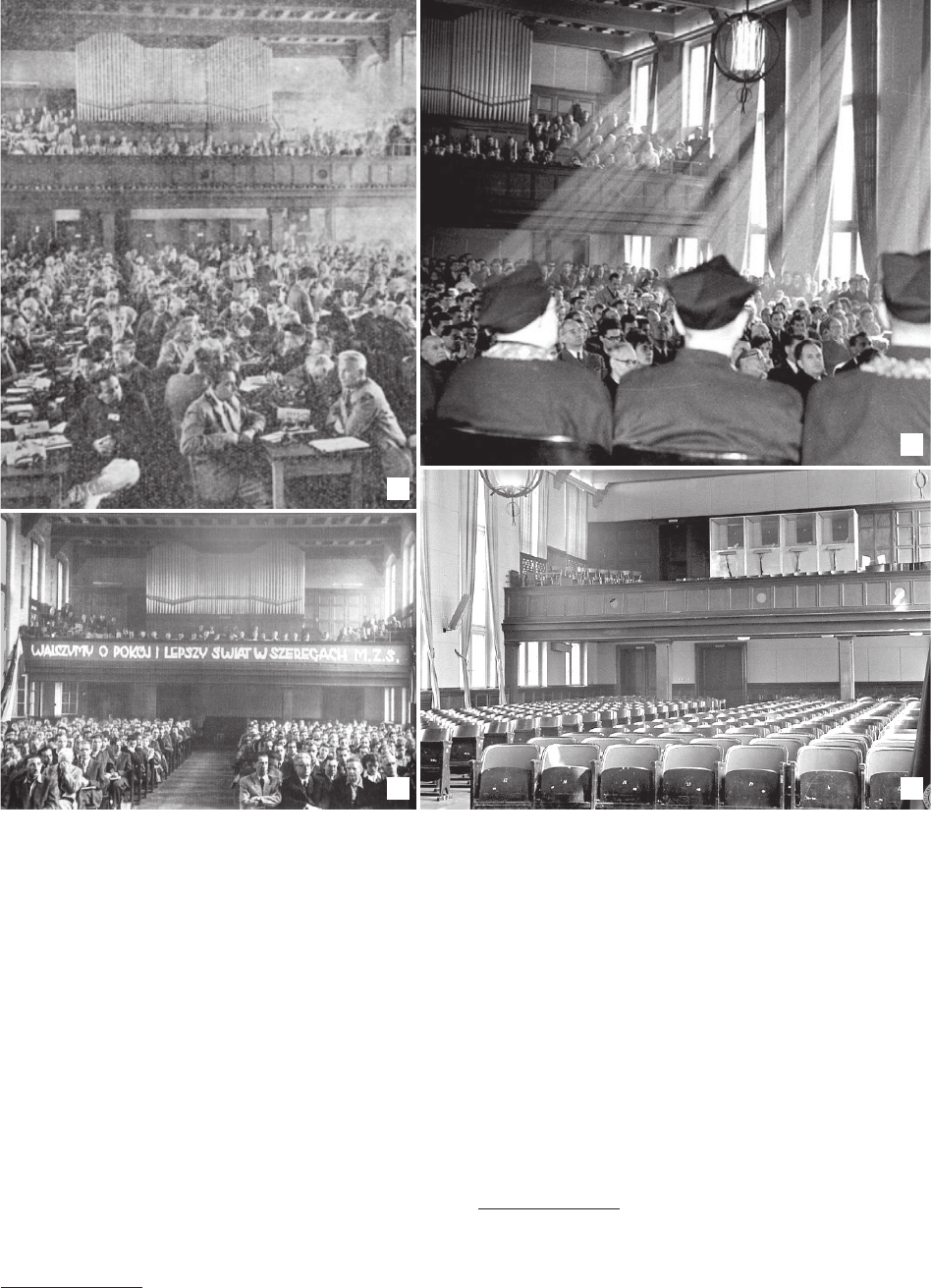

chances of a rapid renovation of the organ. On 25–28 Au-

gust 1948, an extremely spectacular event was to take place

– the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defence of Peace

(Fig. 4a), which was ultimately attended by 400 delegates

from 46 countries. It was part of an exhibition presenting

the achievements of the reconstruction of the Recovered

Territories after the Second World War, which was sched-

uled to be hosted from 21 July to 31 October 1948. The cost

of this gigantic propaganda project was 715 million PLN

(Zwierz 2016).

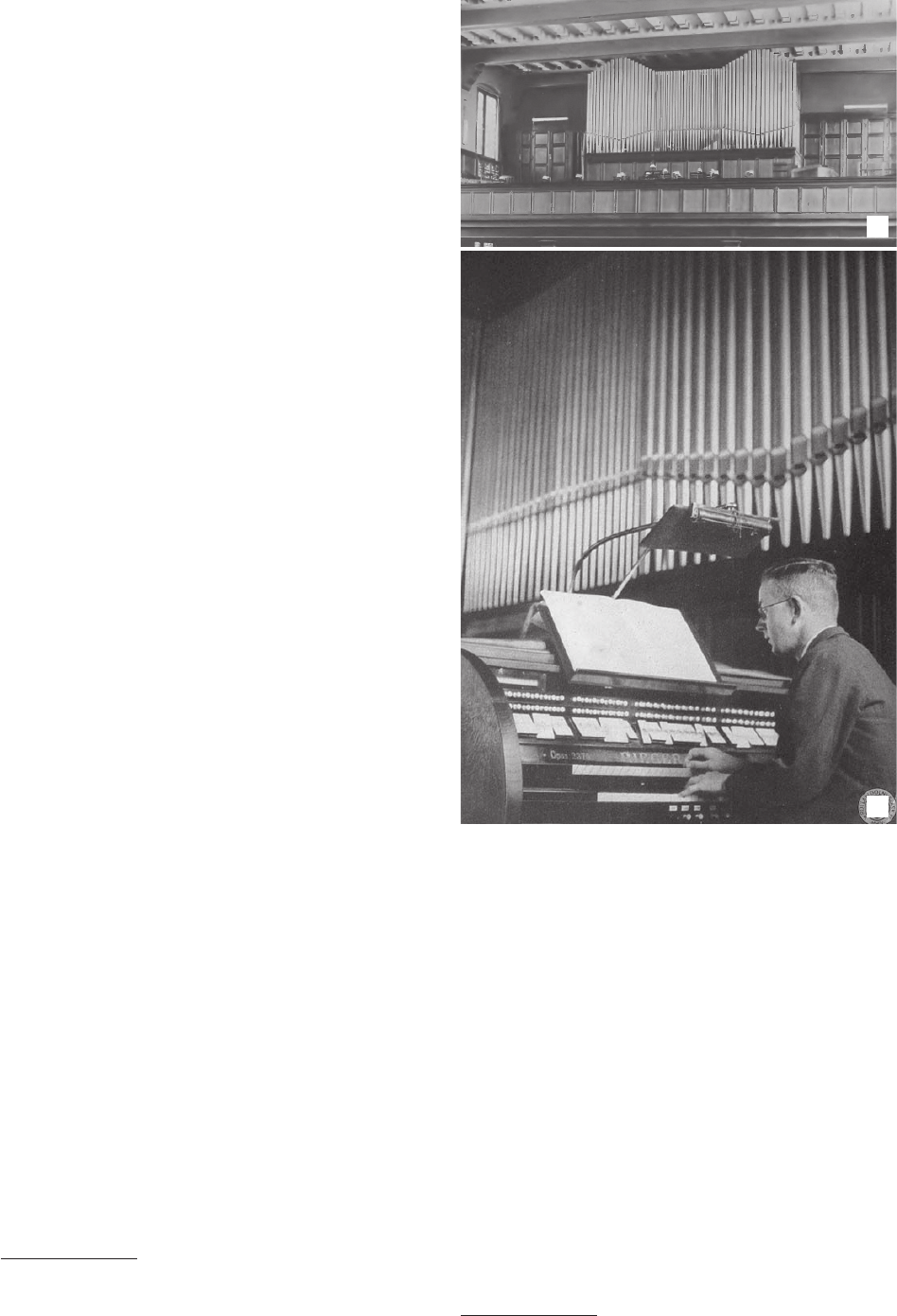

The refurbished instrument was used for various univer-

sity events over the following years, as well as when the

auditorium was made available to external users as a con-

ference or concert hall (Historia jednego zdjęcia 2020)

(Fig. 4b, c). In the 1960s, for example, music classes were

still held here for students of High School II, located on

what is now Parkowa Street. In 1969, Professor Tadeusz

Porębski became the next Rector of the WUST, leading

the preparation and subsequent implementation of a reform

of the educational process and a change in the university’s

structure. His plans also included a renovation of the audito-

rium, tied with the idea to remodel the organ gallery, where

interpreter booths were proposed in place of the instrument.

The organ, which had been renovated 22 years earlier, was

declared redundant, and was dismantled and handed over

to the State Philharmonic in Wrocław (Fig. 4d).

13

It was ul-

timately relocated to the Church of St Mary Magdalene in

Wrocław.

10

Archiwum Politechniki Wrocławskiej, 1947, sign. 135.

11

The Vice-Chancellor justied his request by the fact that only

three days earlier, the proceedings of the 27

th

PSP Congress had taken

place in the hall. Archiwum Politechniki Wrocławskiej, 1947, sign. 122.

12

The commission consisted of pipe organ professor Julian Bi-

dziński (in 1946–1970, director of the Wrocław music school, then

named after Fryderyk Chopin), Dionizy Smoleński and Franciszek Pał-

ka. In their opinion, […] the works listed in the attached cost estimate

were executed expertly. On inspection, it was found: correct intonation

of all voices, clean tuning, the addition of missing voices was adjusted

to the disposition guidelines for organ construction. The entirety of the

repairs was done professionally and soundly (Archiwum Politechniki

Wrocławskiej, 1947, sign. 135, document no. 78).

13

This was based on a decision of the University’s Senate Taken on

20 March 1970. Cf. Brandt-Golecka, Burak and Januszewska (2005, 167,

footnote 66).

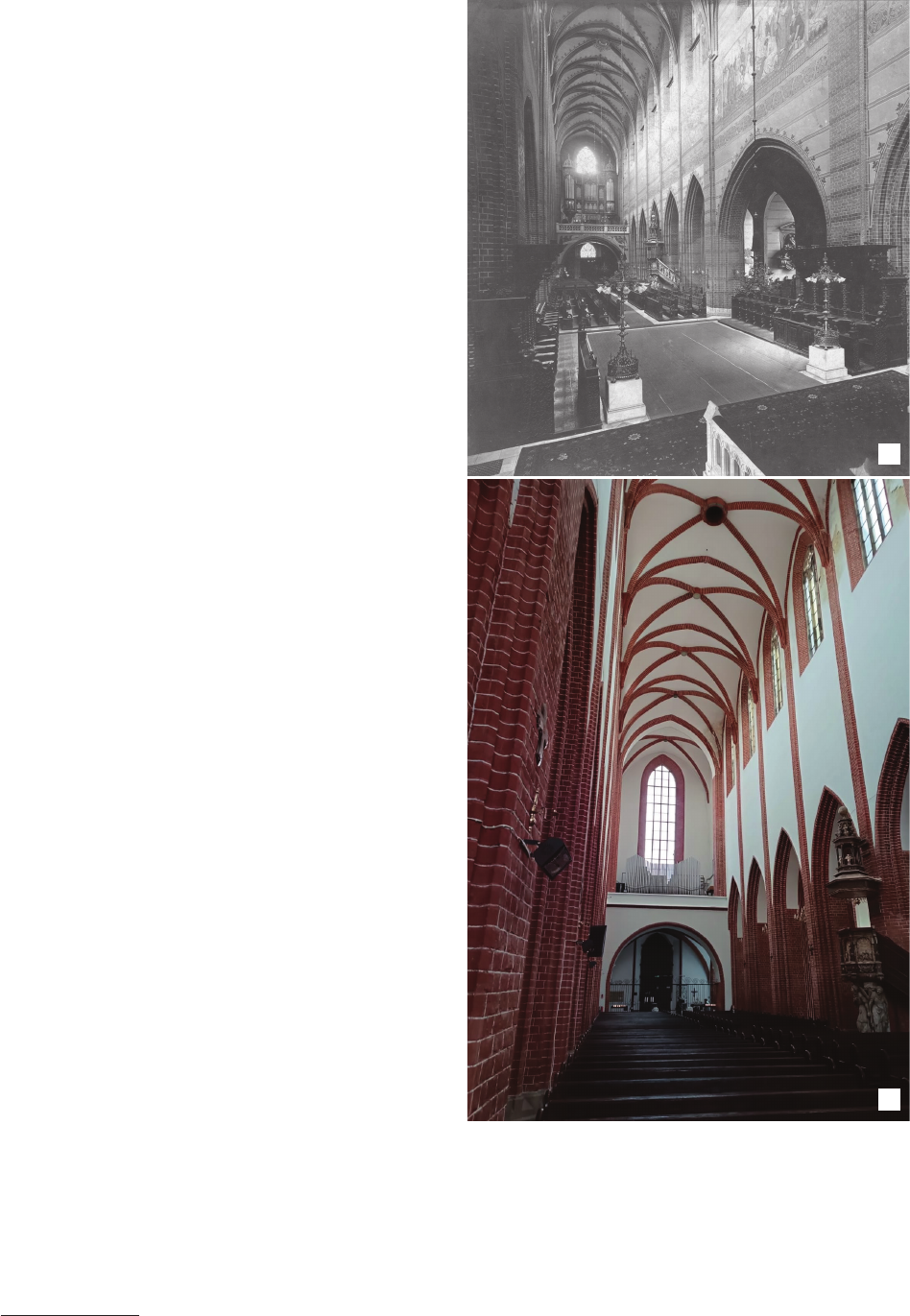

Outline of the history of the organ

in the Church of St Mary Magdalene,

the rebuilding of the church after

the Second World War and the relocation

of the organ from the auditorium of the WUST

Insofar as the Wrocław University and University of

Tech nology had a complex of buildings that had survived

the war from the very start, the state of preservation reli-

gious buildings in Wrocław was marked by heavy losses.

The new state regime, which was hostile to all religions,

nevertheless took great care of the oldest churches, treating

them as testimony to Silesia’s historical belonging to the

Piast dynasty. For these reasons, the reconstruction and res-

toration work also included the severely damaged medieval

Church of St Mary Magdalene. In May 1945, an explosion

tore apart its tower mass, causing part of the south tower and

the west gable to collapse, along with the gallery housing

its great organ, which was completely destroyed. Thanks

to the innovative methods used during the reconstruction,

the tower and gable were successfully reconstructed (albeit

without the tower domes) in 1952. Work on the interior con-

tinued for another ten years, during which the west gallery

was also rebuilt and given a spatial form close to the one

from the Middle Ages. The immense window in the gable

wall above the gallery was also restored (Broniewski 1952).

After the end of the war, the church remained under the

management of the Evangelical parish centred on the city’s

German citizens – services were held in the surviving sacris-

ty in the northern annex. In the 1960s, a Polish-Catholic par-

ish and cathedral were established in the now-rebuilt church.

There was no organ in the interior during the postwar

reconstruction period, a departure from a tradition (Seibt

1938; Kmita-Skarsgård 2013) that had continued since

the Middle Ages

14

, as an organ player of this church had

rst been mentioned already in 1380, and after the per-

manent takeover of by the Protestants, the town council

commissioned the construction of the great organ to Mi-

chael Hirschfeldt of Żary in the late 16

th

century. The work

was completed in 1602, and as early as 1634 a major re-

modelling project was carried out

15

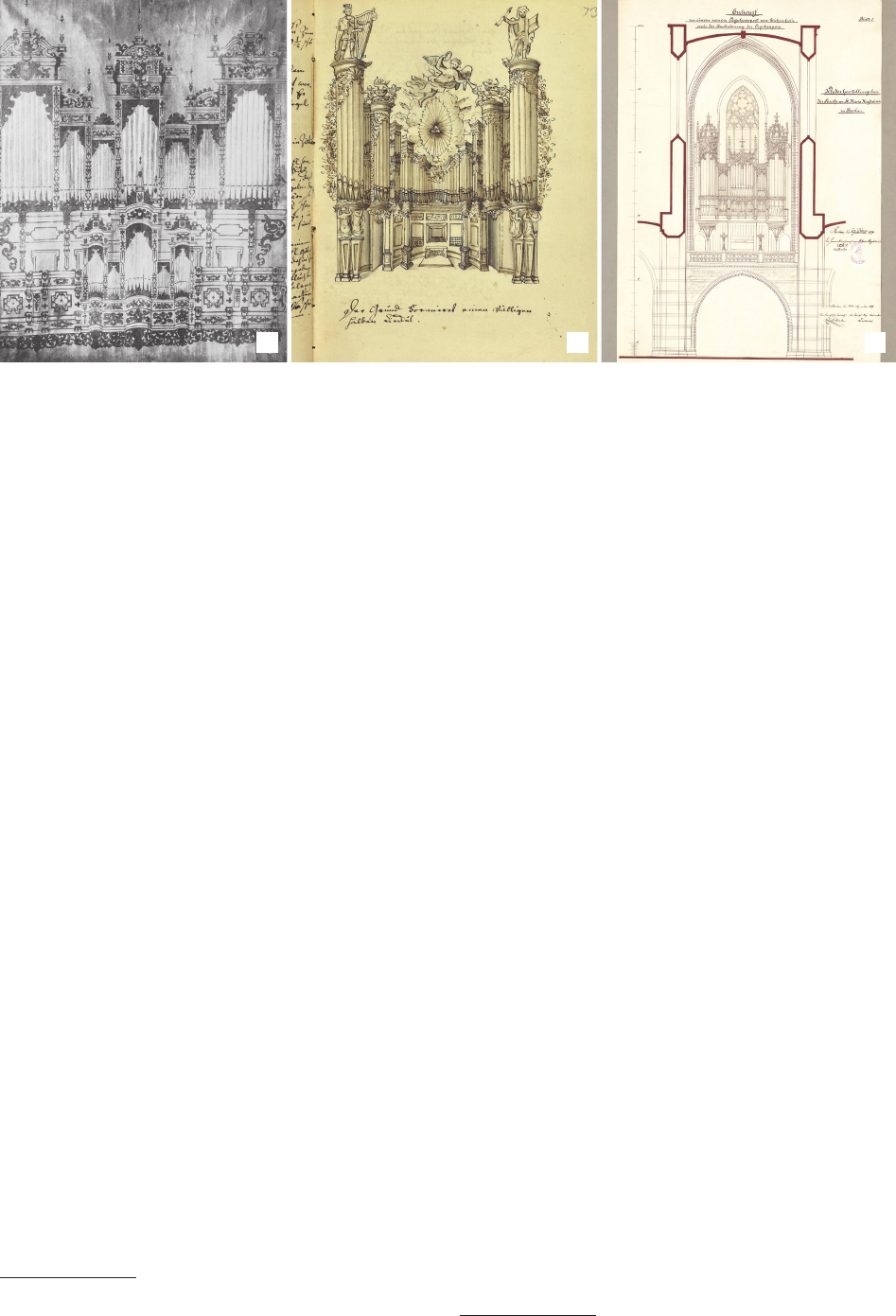

. The following were

preserved: the location on the cantilevered gallery above

the pulpit and the case (Fig. 5a) that consisted of a Late

Renaissance main case (Hauptwerk) and the back positive

(Rückpositiv). The dismantling of the instrument and the

gallery in 1722 was preceded by the construction of a new

great organ, which was planned to be located in the western

gallery (called Burgerchor or Hellenfeldscher Chor). The

builder was Michael Röder from Berlin

16

. The design was

14

The year 1380 is seen as the boundary when an organist named

Gregor was rst mentioned, which attests to the existence of an organ. At

the end of the 16

th

century, the church sported a large organ and a small

organ (700 Jahre St. Maria Magdalena 1926).

15

Michael Hirschfeldt also referred to as Hirschfelder (154?–1602),

with the collaboration of Martin Scheuer, completed the construction of

this experimental organ in 1602. Despite improvements during the con-

struction phase, the technical solution was not successful and the organ

malfunctioned, and a decision was made to rebuild it fully in 1623.

16

Johann Michael Röder (late 17

th

century to the early 18

th

centu-

ry), was a pupil of eminent organ builder Arp Schnitger (1648–1719)