66 Magdalena Żmudzińska-Nowak, Assunta Pelliccio

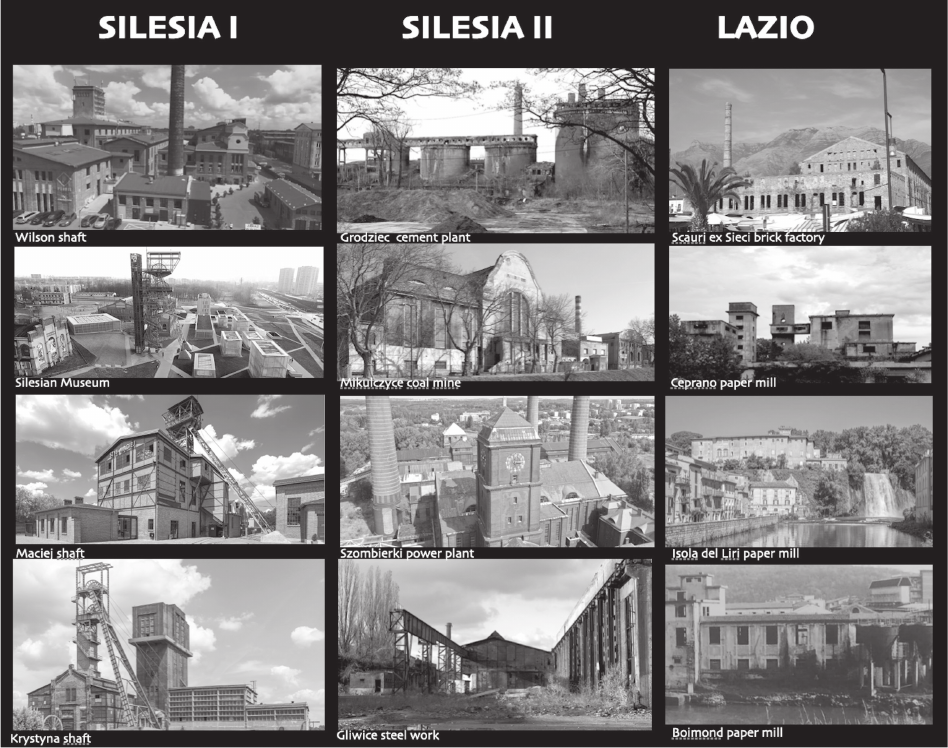

ten years. At the outset, we provide background on the

research area of Southern Lazio and its industrial heritage

and, as a point of reference, selected post-industrial sites of

Upper Silesia.

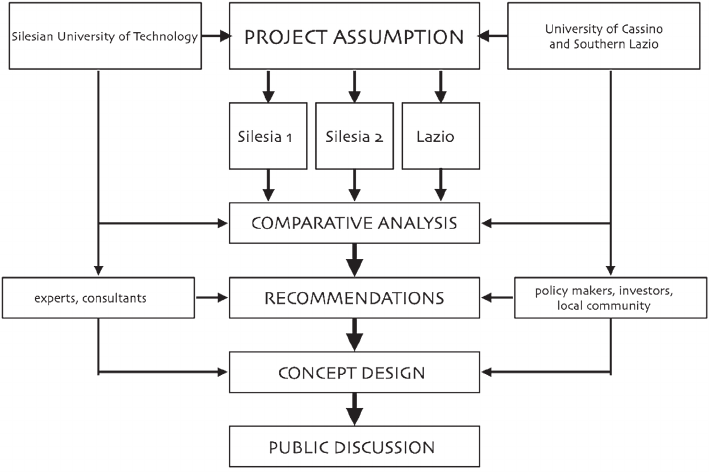

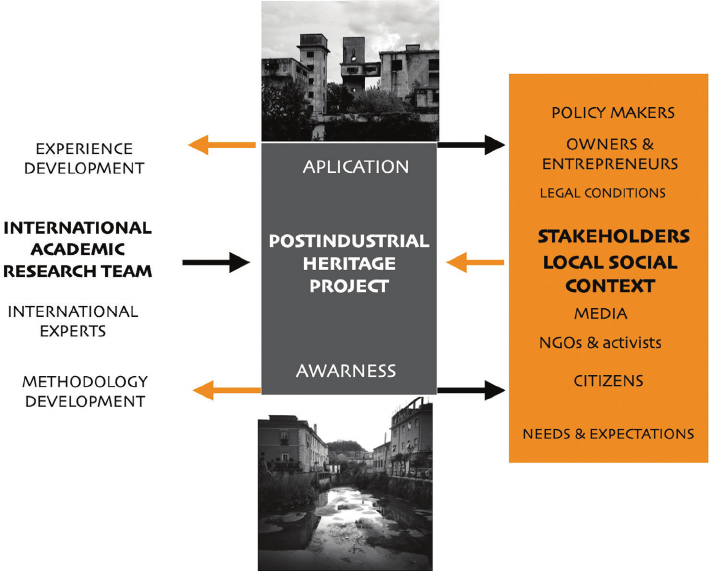

The collaborative research process followed the model

adopted by the authors, which will be described in detail

later in the text. It consisted of several stages: general

research, comparative analysis, preliminary recommenda-

tions, detailed research and case studies, detailed recom-

mendations and proposals for functional and spatial solu-

tions and the presentation and discussion of the results.

Industrial heritage as a subject of research

Although the subject of industrial heritage research

does not have a very long history, the state of research in

this area is extremely extensive. It includes surveys, re-

source inventories, documentation, a review of preserva-

tion approaches and references for adaptation and mod-

ernisation, as well as assessments of potential opportunities

and threats arising from the revitalisation process. The

substance of post-industrial sites varies in terms of type of

industry, time of construction or state of preservation.

Crucial to the state of knowledge of industrial heritage

on a global scale are the research papers and annual National

Reports published by the International Committee for the

Conservation of Industrial Heritage (TICCIH). They pro-

vide data on the state of eorts to protect and promote

post-industrial sites in dozens of countries around the world.

Another group of publications are studies that shaped

the approach to industrial heritage in their time and which

today constitute the literary canon in this eld. These include

fundamental writings on the issue – such as Binney (1984)

and Eley and Worthington (1984) – guides to the conserva-

tion of industrial heritage, reviews of procedures and theo-

retical assumptions (Douet 2012). In turn, the aspect of

identity preservation in the face of transforming post-indus-

trial areas is extensively discussed by Wicke et al. (2018).

Also, publications that provide an overview of the

achievements of the industrial heritage approach in indi-

vidual countries and regions are very relevant to the state

of research. A synthetic summary of the achievements of

the UK’s leading industrial heritage preservation eorts

can be found in a study by Keith Falconer (2006). The

book by Bart Zwegers (2022) oers a multifaceted synthe-

sis of the transformations of industrial heritage with a focus

on Germany and the UK. Likewise, more than 30 years of

Italy’s experience is described in a publication by Massimo

Preite and Gabriella Maciocco (2022), among others. On

the other hand, the Polish experience, the state of research

and the perspectives and research needs have been exten-

sively analysed by Monika Murzyn-Kupisz, Dominika

Hołuj and Jarosław Działek (2022).

Characteristics of the study area in terms

of industrial heritage: Lazio versus Upper Silesia

Southern Lazio is a region with a signicant hydrogra-

phic basin, which – combined with the innovativeness and

hard work of the local population – led to the ourishing of

industrial activity between the 19

th

century and the 2

nd

half

of the 20

th

century (Arcese et al. 2014). The Liri, Gari, Fi -

breno and Sacco rivers and their various tributaries played

a signicant role in the industrialisation of the region, trans-

forming it from a rural area into one of the most industri-

alised centres in the country. Paper mills, textile factories

and various other industrial facilities, powered by hydraulic

mills, sprang up mainly along the river routes of the Liri

Valley, using water as a source of energy. The water of the

Liri Valley rivers is characterised by low temperatures and

properties that prevent the growth of microorganisms, thus

ensuring very high-quality end products. This important

industrial district of the valley transformed rural towns into

proto-industrial “factory towns” (Pelliccio 2020).

Traditional rural houses were also used for industrial

activities, such as weaving, and even castles or noble pal-

aces were often transformed and expanded to accommo-

date industrial activities, e.g., the Boncompagni Viscogliosi

Castle in Isola del Liri (Jadecola 2019). The cultural land-

scape changed, with small mediaeval historic villages

being transformed into factory towns. Within a few

decades, 15 large wool spinning mills were built in the val-

ley, such as in Polsinelli, Zino, Ciccodicola and Manna, as

well as many other medium and small ones, more or less

mechanised. Numerous paper mills – Bartolomucci in

Picinisco, Visocchi brothers in Atina, Lanni brothers in

Sant’Elia, Courrier, Servillo, and Mazzetti in Isola and

Pelagalli paper mills in Arpino and Ceprano (Monti et al.

2020) – employed hundreds of workers, such as Count

Lefrèbre’s paper mill in Isola del Liri, which managed to

provide employment for more than 500 workers. Emilio

Boimond’s paper mill, located on the banks of the Liri

River in Valdurso, is one of the few mills that has preserved

antique machinery, including the so-called endless machine

introduced in the industrial triangle of Arpino, Sora and

Isola for the production of large sheets of paper (Dell’Ore-

ce

1984; Mancini 2016).

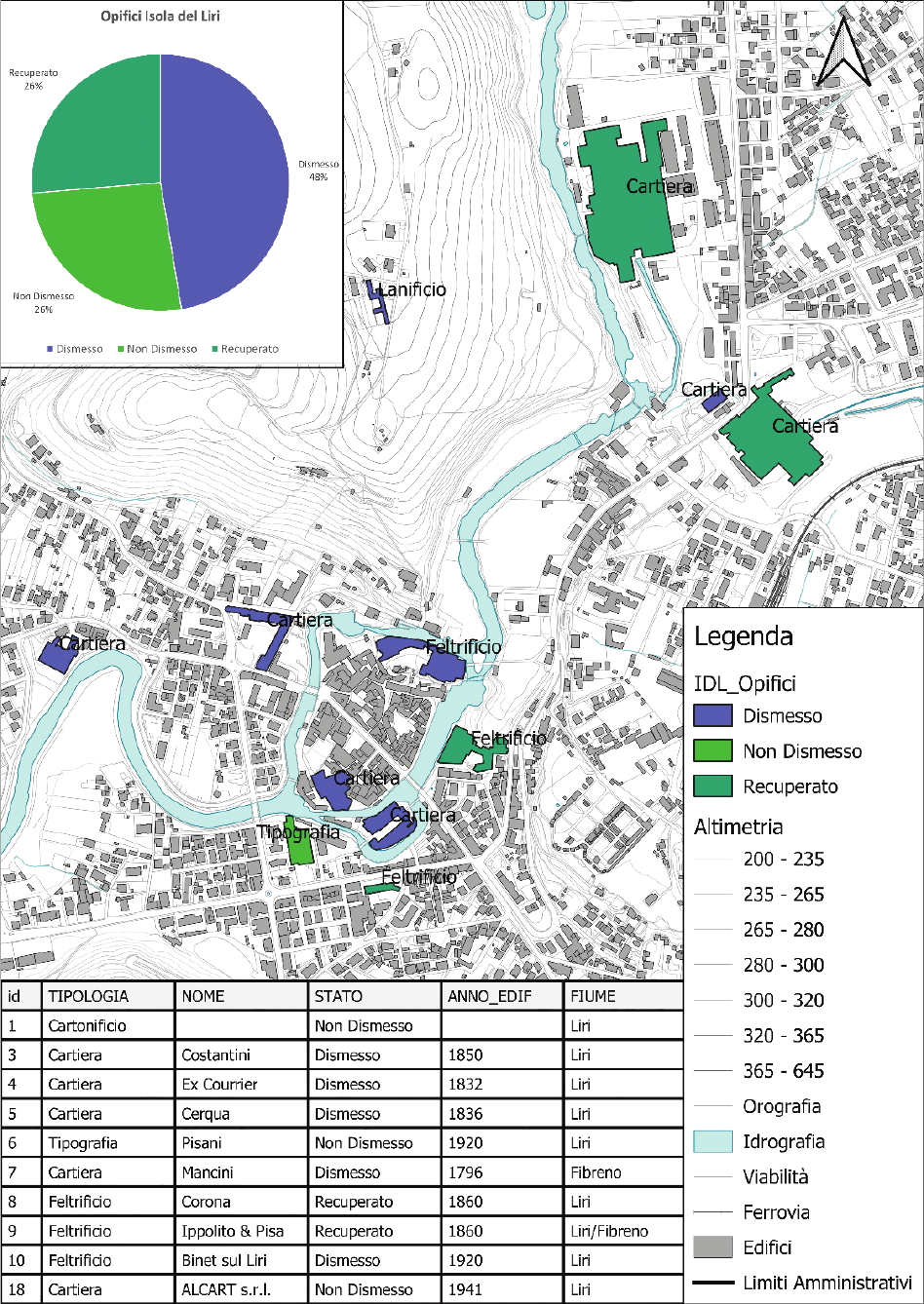

Most of these factories could not withstand the devasta-

tion caused by World War II and the market demand for

technological innovation. They gradually ceased opera-

tions until eventually closing. Today, most of them, many

of which are still privately owned, are completely aban-

doned. For example, in the small village of Isola del Liri,

once highly industrialised, four large paper mills and three

felt factories are housed on an area of just 0.06 km

2

, all of

which are now abandoned, except for one that has been

converted into a multipurpose building (APAT 2006)

(Fig. 1).

Thus, the industrial identity of the region has been almost

completely obliterated. While the remaining unused facili-

ties still hold signicant cultural and architectural value,

they have not been the subject of wider interest to date.

Upper Silesia is one of Europe’s largest regions of heavy

industry; it developed strongly starting in the 19

th

century’s

great industrialisation. After World War II, the Upper

Silesian Industrial District (GOP) formed the largest min-

ing and metallurgical operations area in Poland and one of

the largest in Europe. More than 50 coal mines, 43 of them

in urban areas, operated on the basis of complexes of his-

torical facilities that were constantly modernised and