10 Aleksander Piwek, Tomasz Jażdżewski

also its artistic decoration. The size of the works, which

entailed considerable costs, and their advisability indicate

that the new function introduced was of great importance

to the chapter. Therefore, it is very likely that the room

was converted into a chapel.

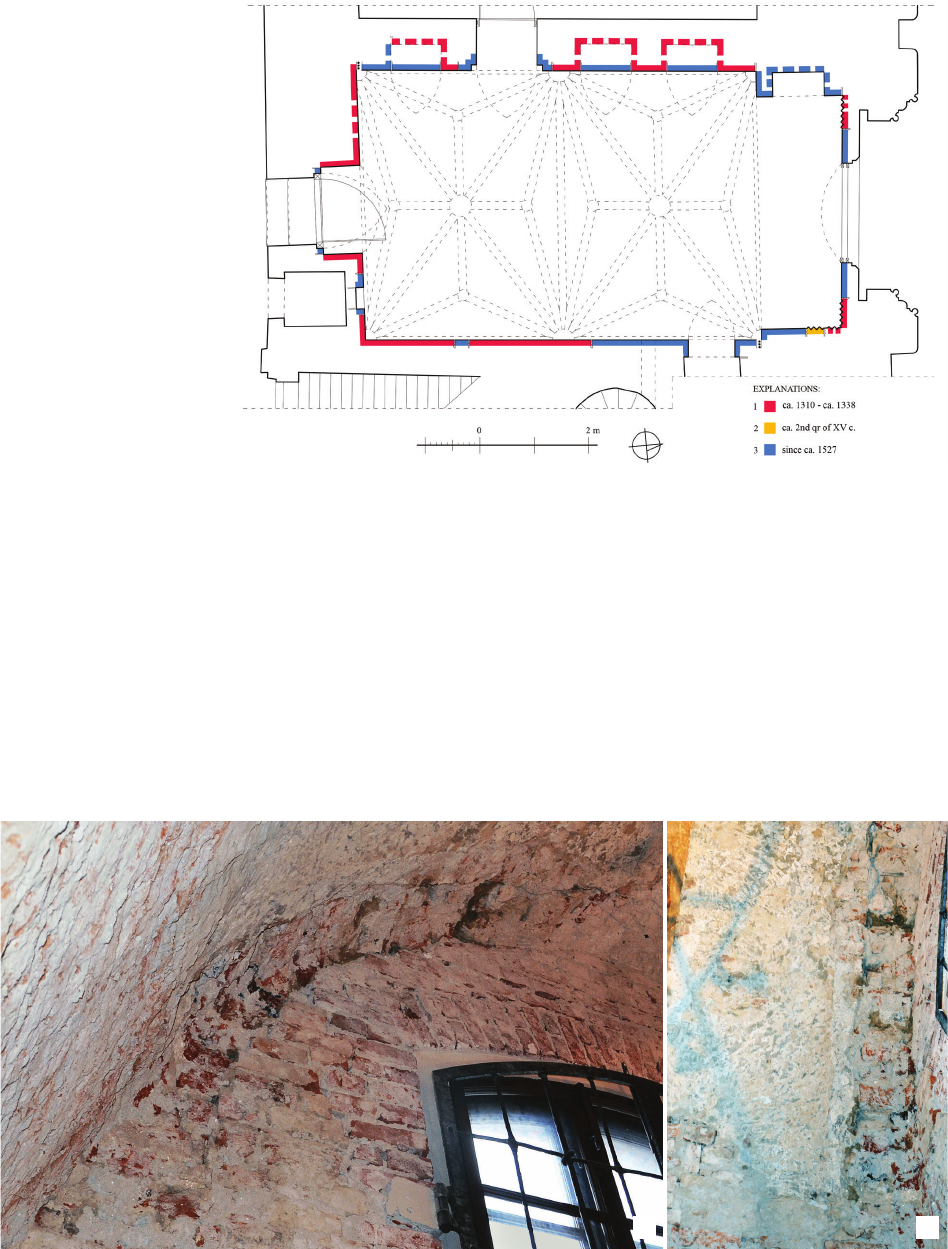

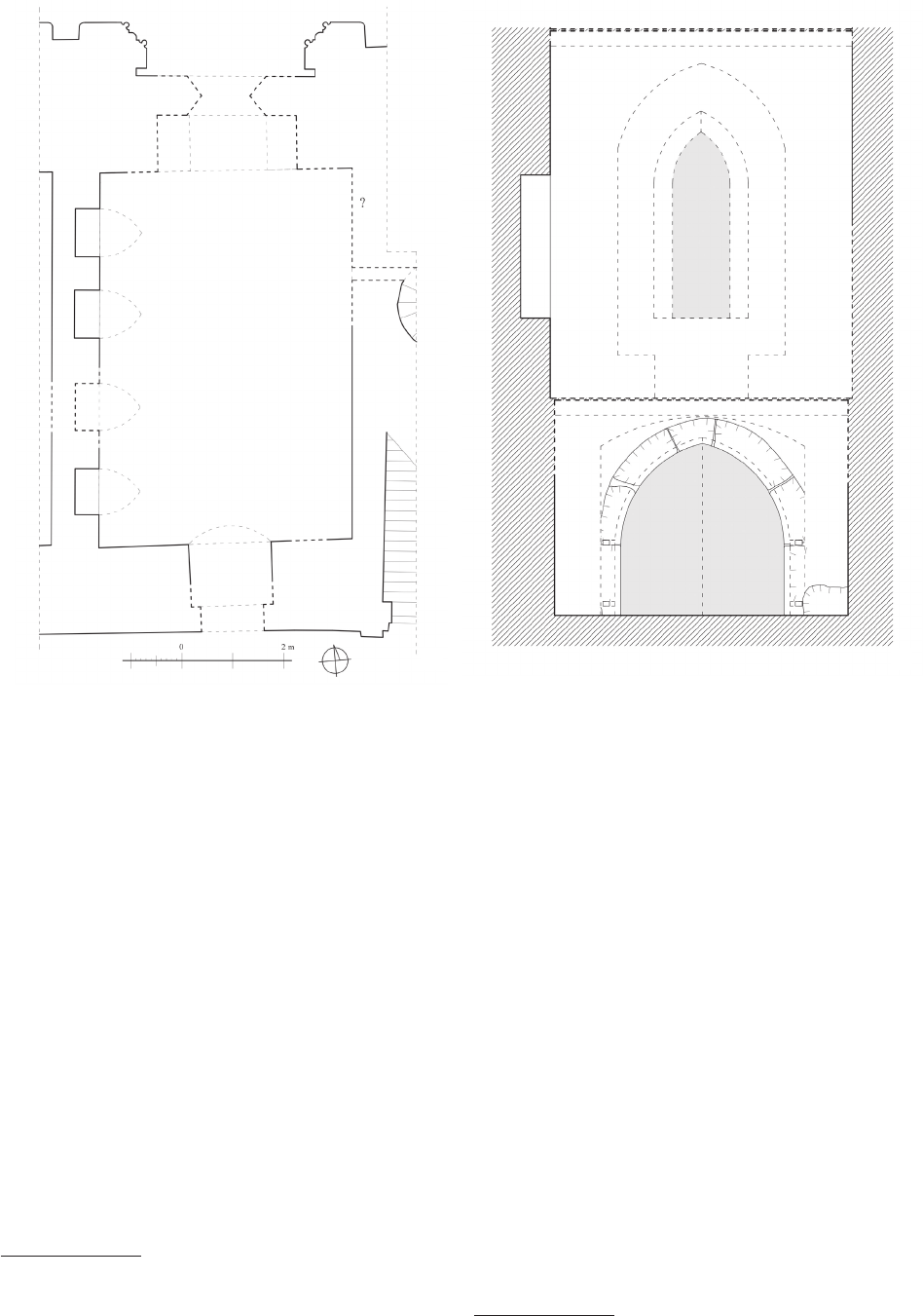

This is evidenced by some newly found information.

It mainly relates to the reconstruction of the northern

part of the room. As stated, the closing window wall was

narrowed by approx. 40 cm, leaving actually only a thin

brick partition. The wall was tted with new bricks for

a wider recess. The previously massive side walls were

cut down, removing approx. 60 cm of masonry on both

sides and narrow pilaster walls were created using new

bricks. As it was not easy to achieve a homogenous sur-

face, the unevenness between the inserted corbel arch

bricks in the northern wall and the additional ones set on

the pilasters was compensated for by covering them with

plaster of various thicknesses. Over the years, the only

evidence of such works were visible cracks. Thus, the

new recess became 400 cm wide and 155 cm deep. These

radical measures, which could have led to a partial dete-

rioration of defence, had one aim – to gain a substantial

area (155 × 400 cm) with a permanent base, supported by

a pointed stone gate frame and an adjacent brick, segmen-

tal porte cochère arch. As it was assumed, this substantial

undertaking served to make room for a brick altar set on

a permanent base. It may have stood against the wall, rein-

forcing its structure, or it may have been far enough away

from it so the window could still be used.

The rest of the room was covered with two parts of

the stellar vault. It was placed 50 cm above the new re-

cess. The ribs of the vault were set on supports. They were

placed in the corners and in the middle of the longitudi-

nal walls. Recent restoration work has revealed fragments

of the original supports and the vaulting ribs that go up

to them. These details were made of articial stone [10,

p. 11]. It consisted of lime-gypsum mass, quartz, crushed

ceramics, charcoal and wooden bres [10, p. 11].

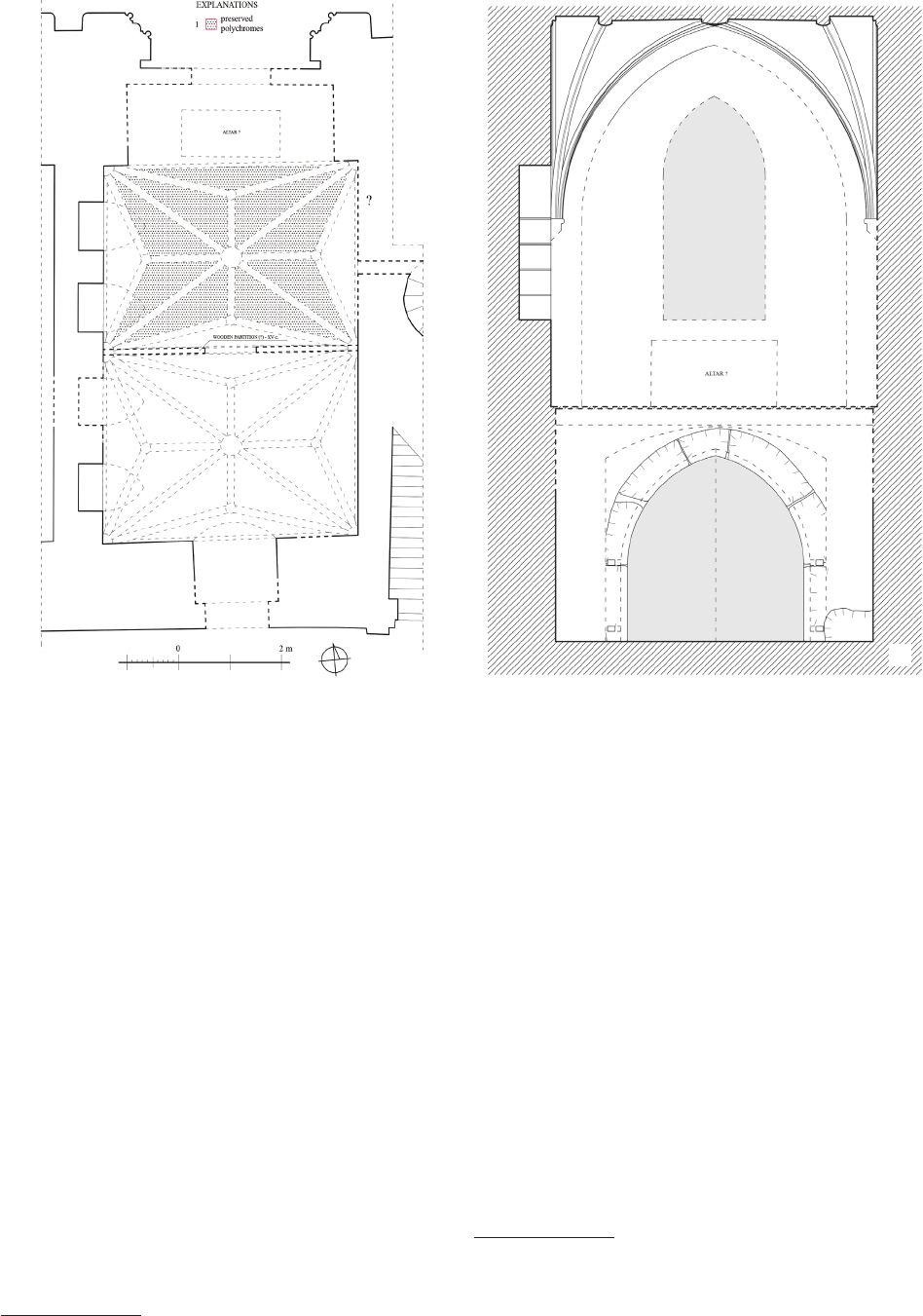

The completely uncovered polychromes (Fig. 9) indi-

cate the sacral function of the room and the time of its

creation. It is assumed that they were made between 1400

and 1450 [10, pp. 8, 9], although this is not the only pos-

sibility

13

. Their sacral content (gures of saints) corre-

sponds with the new use of the hall. Their appearance only

on the vaulting of the northern bay has not been explained

yet. The suggested reason is the start of the war in 1409 [9,

p. 8] and its consequences. There is also another explana-

tion. When a wooden partition is placed in the middle of

the interior, it separates parts intended for users of dier-

ent status – the clergy and the castle servants.

Three arguments have recently been put forward

against the theory of a sacred function of the room [11,

p. 294]. The rst was the absence of consecration crosses

on the walls. However, their absence is not certain. Me-

dieval plaster may have survived only on those parts of

the walls which are Gothic

14

. The old plaster found at the

height of the occurrence of possible consecration crosses

was preserved only in two places: the western part of the

southern wall and the northern part of the western wall

(a fragment between the rst and the second recess from

the north may also be taken into account). However, it is

uncertain whether the plaster found there dates from the

Middle Ages. The second argument is related to the lack

of orientation

15

. The room is arranged on a north-south

axis, but it must also be taken into account that the sacral

function would have been secondary and had to allow for

13

Stawski [9, p. 8] points to the time of the rst 10 years of the

15

th

century, while Raczkowski [11, p. 292] points to the end of the 14

th

century, although he noticed the possibility of setting the site during the

reign of Bishop Jan Mönch, i.e. at the end of the 14

th

century/beginning

of the 15

th

century.

14

At the same time, this term does not mean medieval plaster. The

potential for error in his discernment is evidenced by the case of the east-

ern wall of a window recess. According to 1994 documentation [8], on

its central part, Gothic plaster with traces of painting was found. How-

ever, the research carried out in 2017 indicated that this wall contained

gothic bricks chipped or lled with material classied as modern [12].

Another nding is the presence of Gothic plaster in the centre of the

recess’s lower plane of the arch and in the recess of the western wall of

the recess, which was created in the 19

th

century, as well as part of the

corbel arch forming the recess.

15

In castles and churches, the location of chapels with respect to

the eastern direction was customary.

Fig. 9. Part of the northern bay vault

with traces of exposed polychrome (2

nd

quarter of the 15

th

century?)

(photo by A. Piwek)

Il. 9. Część sklepienia północnego przęsła

ze śladami odsłoniętej polichromii (2. ćw. XV w.?)

(fot. A. Piwek)