12 Janusz Maciej Nowiński

A grey colour of the rock and a carbonate character in

combination with the location of the object from which

the sample was taken may suggest the origin of the rock

raw material in which the baptismal font from Gotland

Island was made. Silurian limestone found here is very

often found in the architectural details of Northern Po-

land. However, typical limestone varieties have a biogenic

character and abound in numerous carbonate bioclasts.

The so-called limestone from Hoburgen, which is rich in

sparite cement, is similar to the sample in terms of petro-

graphic features [25, p. 1]. Hoburgen limestone deposits

are located at the southern end of Gotland and form a cli

coast of this part of the island.

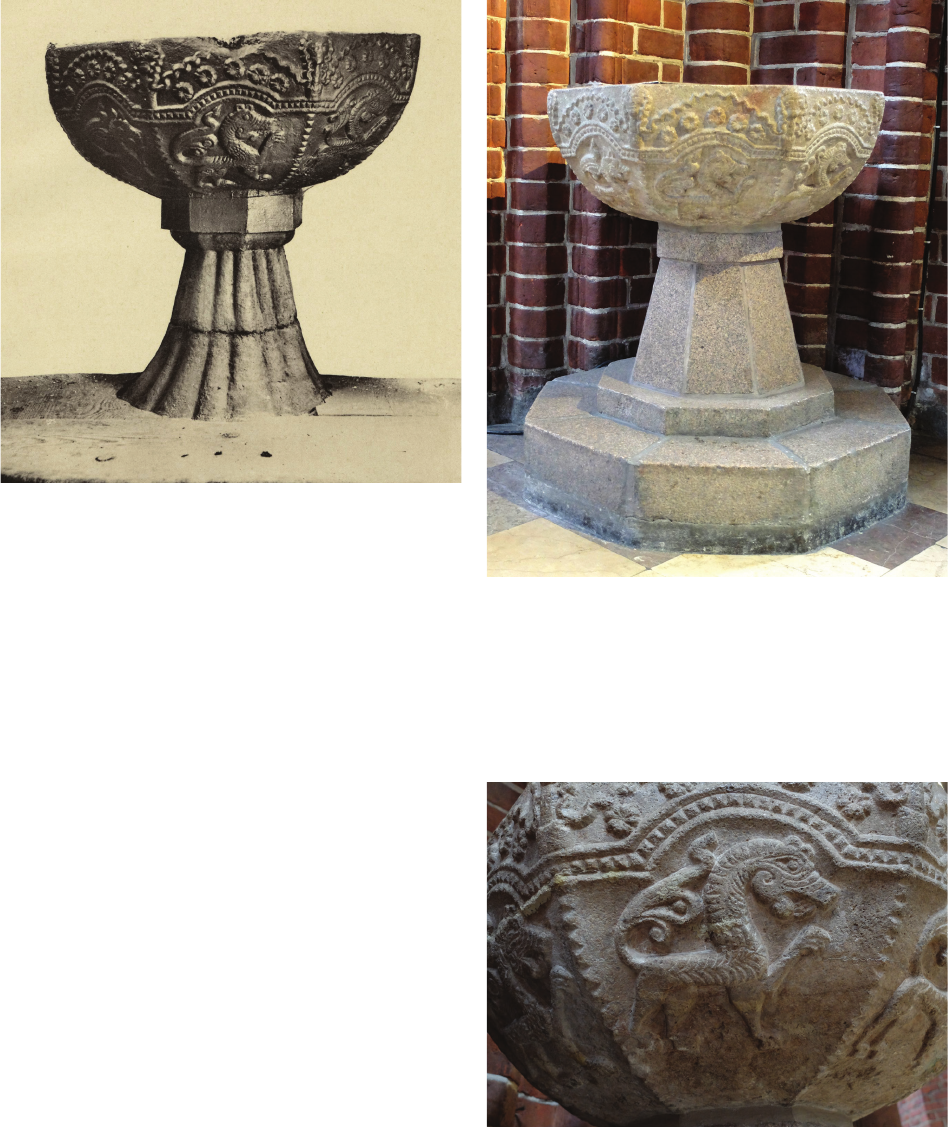

Summing up the discussion on the authorship and or-

igin of the baptismal font from St. Nicholas’ Church in

Grudziądz, it is possible to indicate not only the Gotland

models which its author used, but also the Gotland prov-

enance of the stone in which it was carved – deposits of

limestone Hoburgen. Therefore, this work should be treat-

ed as an import from Gotland.

Iconography and ideological content

of the baptismal font decoration

The shape and decoration of baptismal fonts in the

Middle Ages resulted from the fact that they stored bap-

tismal water solemnly consecrated once a year (on Holy

Saturday) – the only and irreplaceable matter of the sac-

rament of baptism, fundamentally dierent from the so

called holy water, commonly used in liturgical ceremonies

and in the devotional practices of the faithful. An import-

ant element of the ceremony of consecration of baptismal

water was its exorcism, through which – freed from all

devilish power – it became a holy source of cleansing

and regenerative water. Those washed in it during bap-

tism were fully puried from sins and freed from evil. The

consecration of baptismal water made it a holy and sancti-

fying thing, a carrier of divine power, fruitful in salvation

[1, pp. 107–111].

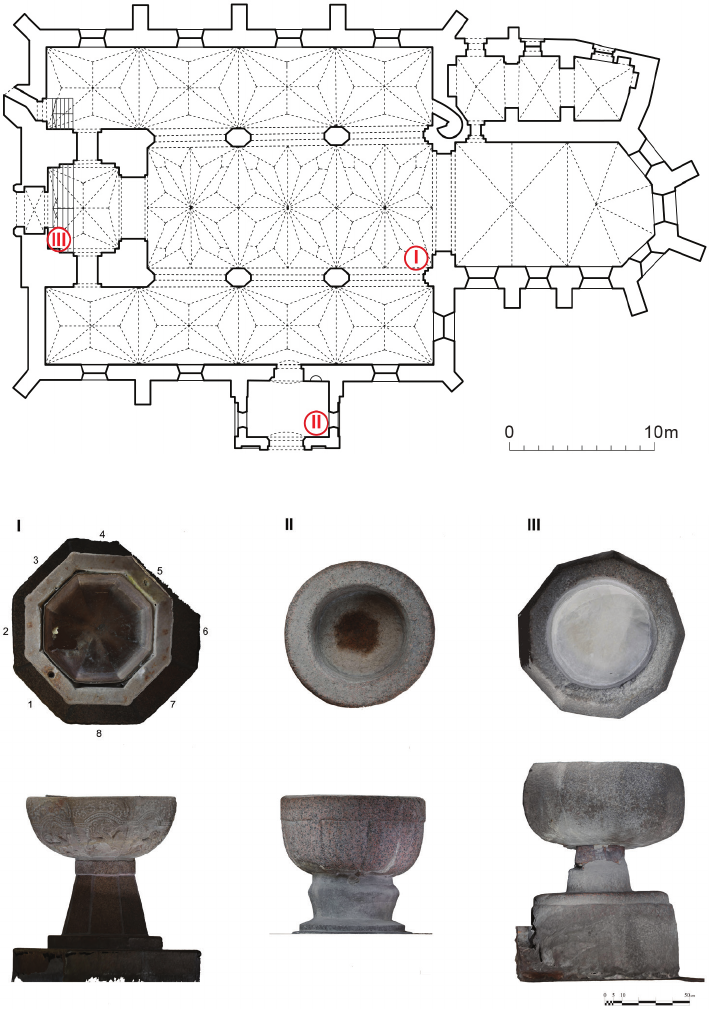

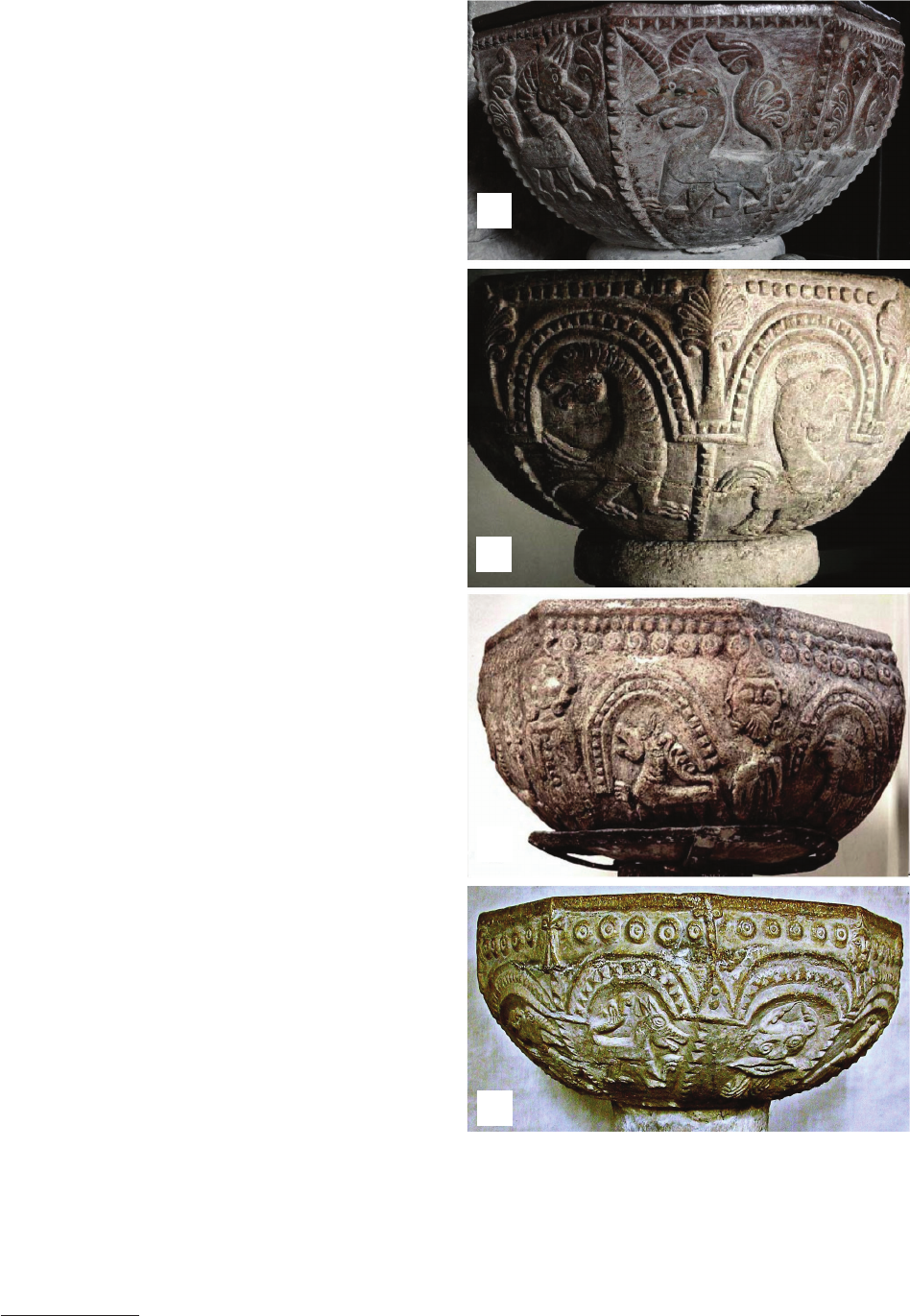

The presence of consecrated baptismal water in the

baptismal font resulted in its shape (originally cylindrical)

being dierentiated, formally separating a bowl with water

from the base. According to the early Christian tradition

continued by the Roman Church, the shape of the bowl in

the late Middle Ages was usually octagonal, symbolizing

rebirth to a new life through baptism and the promise of

resurrection [1, p. 111, especially note 24]. The symbolic

shape of the bowl was accompanied by its ornamentation,

which could emphasize various contents related to the es-

sence of the sacrament: the holiness and life-giving nature

of baptism, the victorious power over evil, the transforma-

tion of the baptized, the hope of salvation through Christ

and with Christ, the reality of paradise. The artistic and

iconographic distinction of the bowls of baptismal fonts

emphasized the presence of baptismal water in them, pro-

viding the faithful with visual proof of the holy power and

eectiveness of the sacrament.

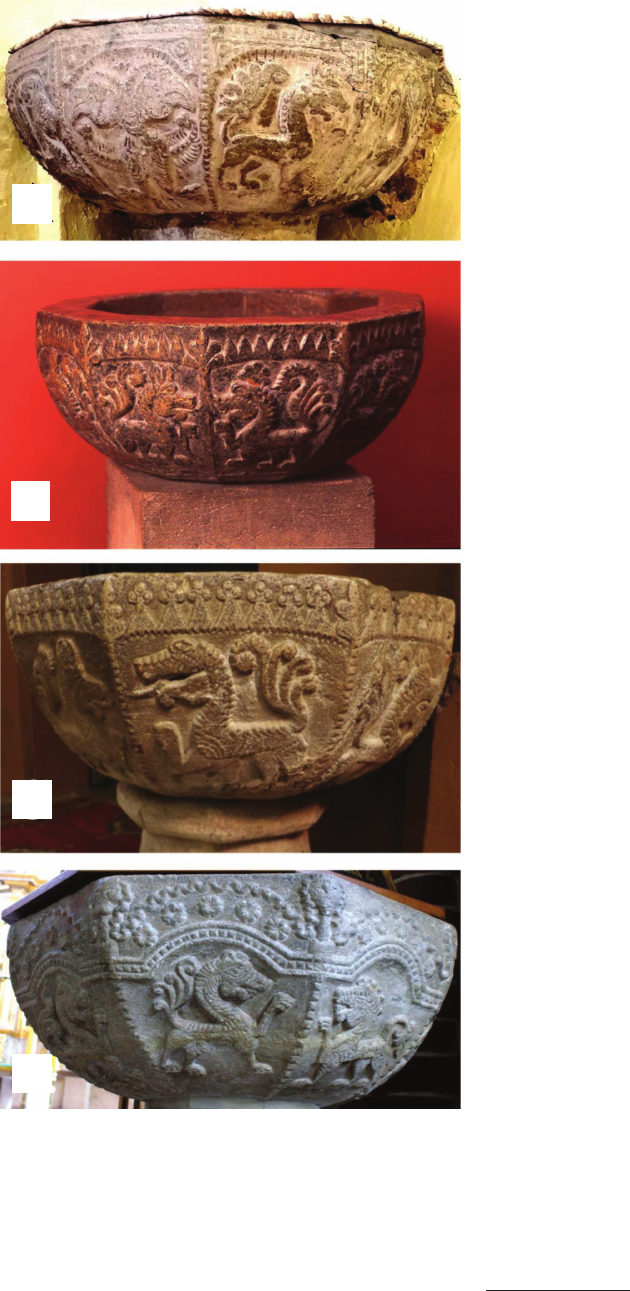

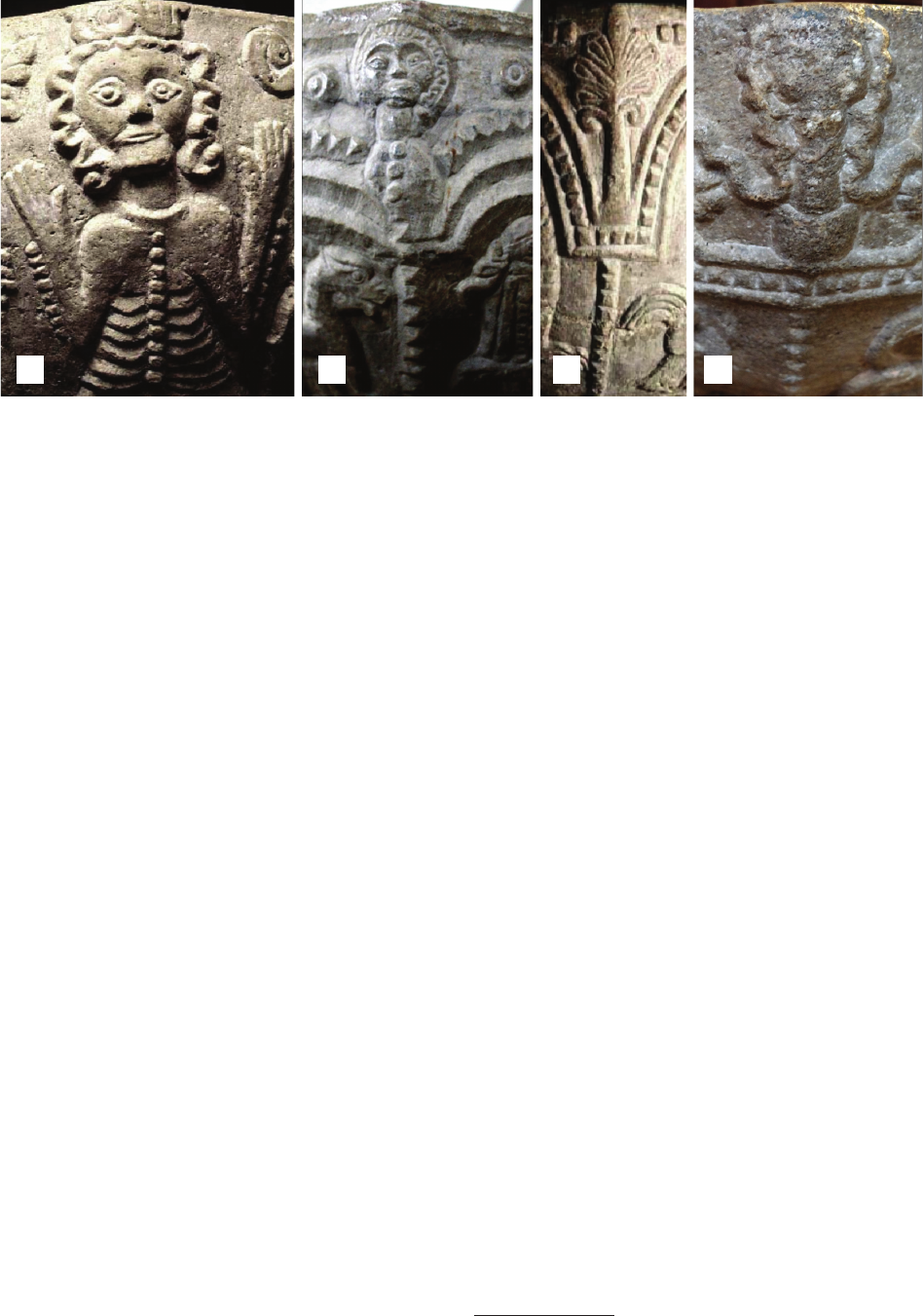

The above-mentioned ideological content related to the

form and decoration of medieval baptismal fonts was fully

realized in the case of the baptismal font from the parish

church of St. Nicholas in Grudziądz

15

. In order to illus-

trate the theological message (which was probably pre-

sented to him by the person who commissioned the work

– this will be discussed later), the creator of the baptismal

font – in accordance with the tradition long present in his

artistic environment (Master Byzantios) – used symbolic

representations of animals, whose iconography and dra-

ma of the action with their participation were taken from

the already mentioned medieval bestiary – the Physiolo-

gus [21]. As already emphasized, the composition of the

bowl decoration has its center, which is a eld with the

representation of a lion (Fig. 7). The treatise Physiologus

also begins with a description of the lion, which considers

it the king of animals, symbolically referring it to Christ.

The Physiologus describes three types of lions, and the

rst type is illustrated on the baptismal font: a carved lion

stands calmly, has a curly mane, a noticeably large head

and an accentuated tail

16

.

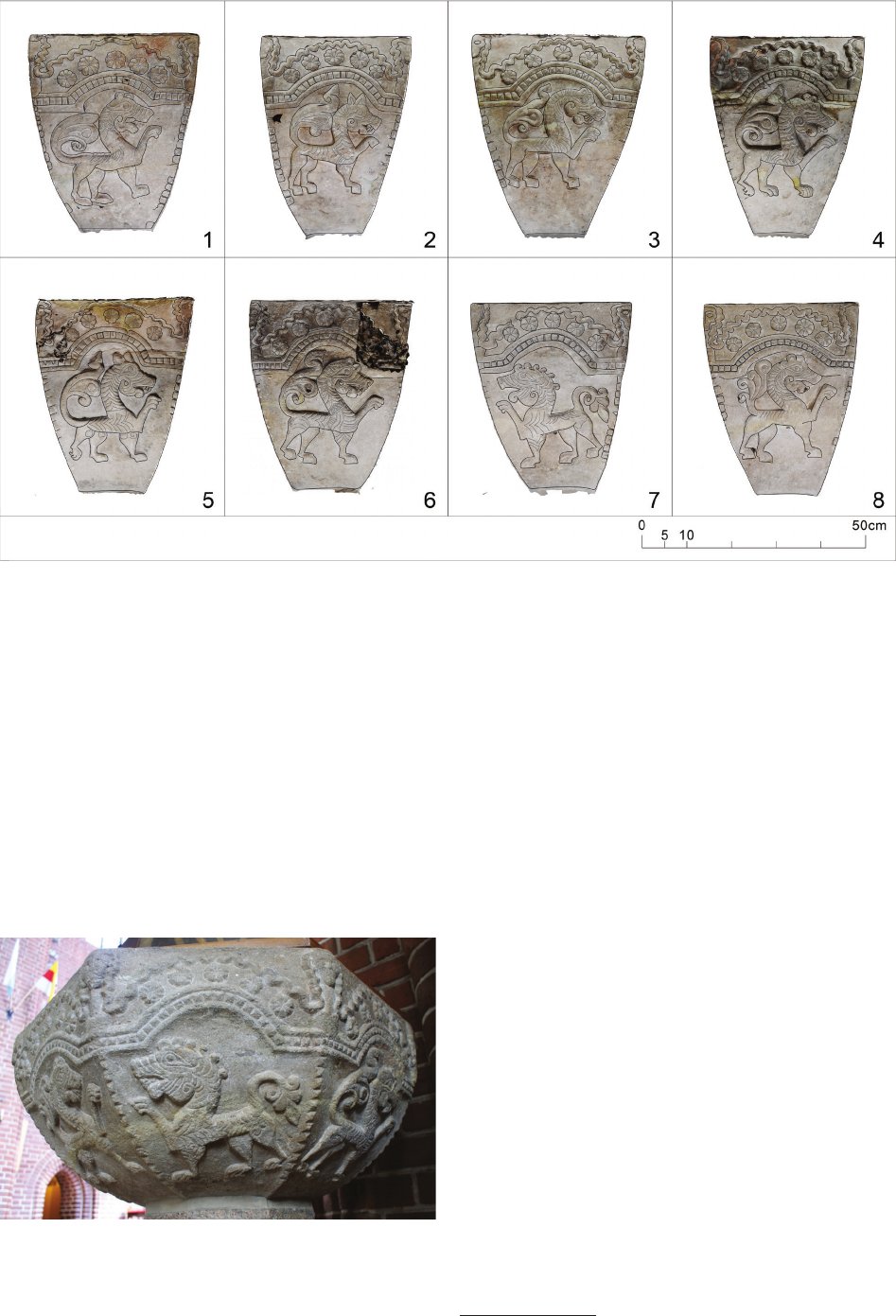

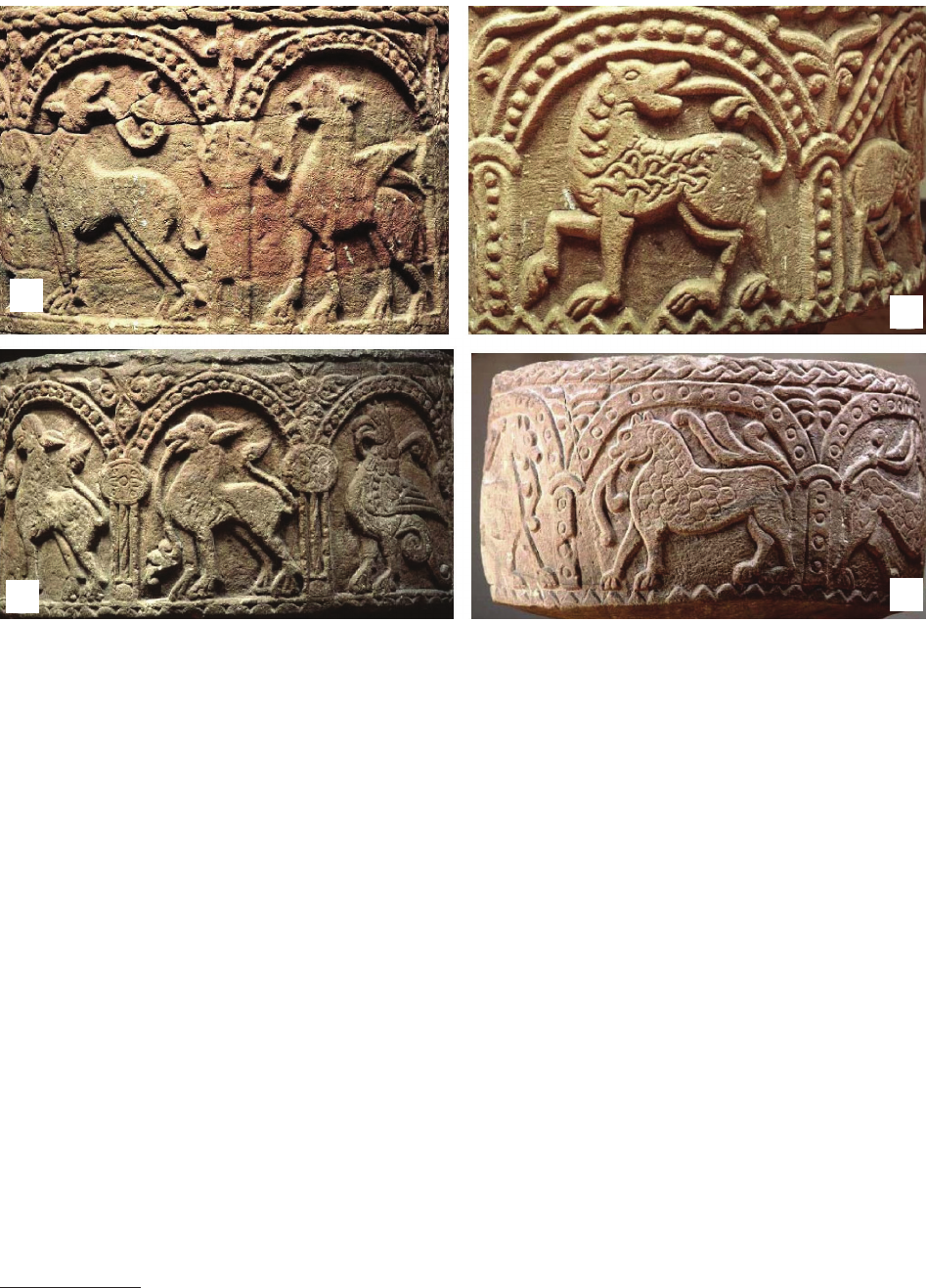

The remaining seven animals, which have toothed

mouths and paws with claws, short hair and maneless

necks, are dicult to identify zoologically due to their or-

namental styling. Their representations on the baptismal

font in Grudziądz represent the images of beasts described

in the Physiologus

17

. These beasts, just like in the bestiary

works by Master Byzantios and his followers and in Frö-

jel Group, are devoid of savagery and aggression

18

. Their

symbolic representation and importance in the baptismal

font decoration program is evidenced by the fact that the

artist deprived them of animal tails, replacing them with

oral forms – fancifully curled plant tendrils (Figs. 5, 6).

Describing the dragon, considered a symbol of Satan in

the Middle Ages, the Physiologus states that dragon ven-

om is not found in the teeth, but in the tail [21, p. 63]. As

mentioned above, washing with exorcised baptismal water

during baptism also resulted in exorcism – freedom from

evil and its power. In this case, depriving the beasts of their

tails – a symbol of devilish power – and replacing them

with lush plant tendrils illustrates the eect of the exor-

cism performed in baptism

19

. Receiving the sacrament had

15

In 2016, an article by Marek Szajerka was published on the sym-

bolism of the Grudziądz baptismal font. It is dicult to argue with this

text, the author of which, setting out to identify the symbols of the bowl

decoration, does so on the basis of incorrect identication of artistic

forms and iconography, and the interpretation is based on subjective as-

sociations, without references to the artistic, iconographic and symbolic

tradition [26].

16

There are three types of lions, some are small, curly-maned and

calm, others have an elongated body, and still others have a straight

and sharp mane. Their feelings are expressed in the head and tail, their

courage is in the chest, and their strength is in the head [21, p. 38].

17

The name of beast rightly belongs to lions, leopards, foxes, ti-

gers, wolves, monkeys, bears and others that use both mouths and claws,

with the exception of snakes. They are called beasts because of the power

thatmakesthemerce [21, p. 38].

18

According to Kuczyńska, beasts […] devoid of the expression of

destructive power, […]theirstiandposedguresonbaptismalfonts

from the 14

th

century seem to have primarily a decorative role [5, p. 28].

19

This way of illustrating evil tamed by holy action occurs, among

others, in the decorations of Romanesque portals – masks with plant

tendrils coming out of the mouth (e.g. Czerwińsk around 1140, Wrocław

portal from Ołbin, 1230s) and in the programs of monastic and canoni-

cal stalls, where dragons acting as canopy partitions and supports, have