124 Tomasz Omieciński

about their own work may be, the critic has a broader per-

spective and knowledge of parallel currents, and sees cor-

relations between art and other areas of human life. It is not

the artist who explains his work, but vice versa – we can

understand the artist through the work (Morawski 2007,

127). As Tatarkiewicz writes, for the artist, styles […] are

a necessity, because they correspond to the way of looking,

imagining, thinking of their time and environment. They

are mostly unaware of them; the critic, especially the histo-

rian, is more aware of them than the artist (1982, 204–206).

Hence, it is usually the critics who can more accurately de-

scribe the inuences and causes of a particular work.

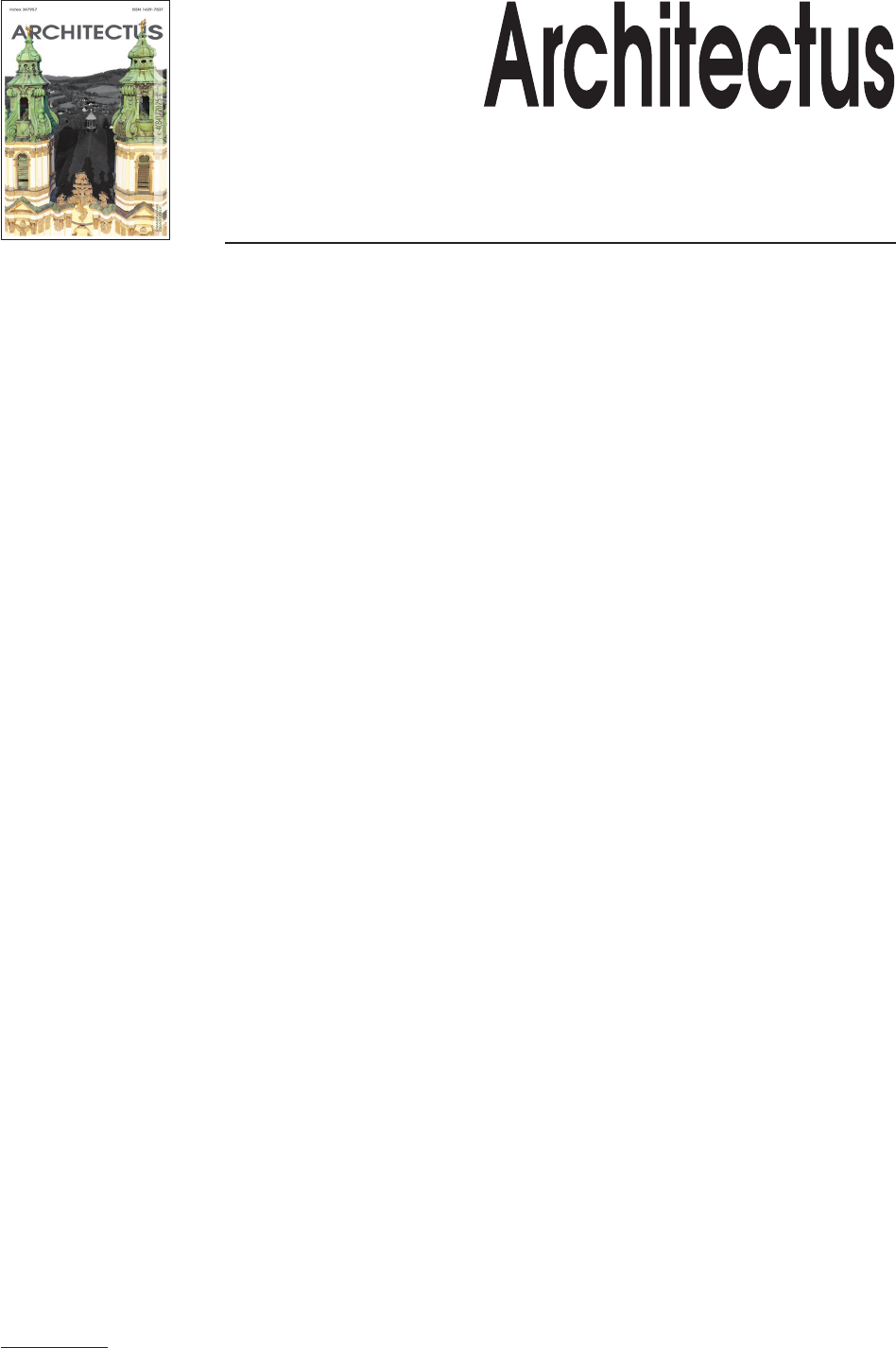

An example from the world of architecture is the descrip-

tion of the deconstructivism trend created by Mark Wigley

and Philip Johnson. The Deconstructivist Architecture ex-

hibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1988, which they

curated, featured the works of seven architecture studios or

architects. Similar in aesthetics, they were brought together

under one banner – deconstructivist architecture. The artists

themselves had operated without awareness of the existence

of such a community until then, and most of them, despite

following similar intellectual paths in places, rejected the

common designation of “deconstructivists” (McLeod 1989,

43, 44). To this day, Peter Eisenman maintains that decon-

structivism in architecture, as described on the occasion of

this exhibition, did not exist, and that some of the major

assumptions of Wigley’s reasoning are wrong (Eisenman

2022). After more than 30 years have passed, it must be

acknowledged that architectural criticism has adopted Wig-

ley’s outlook – the term “architectural deconstructivism”

and the selection of its representatives are widely recog-

nized and understood according to the 1988 exhibition cat-

alog. The division between “deconstructivism” and “decon-

structionism” emphasized by Eisenman, which stems from

philosophical assumptions, does not seem to be as strong

a demarcation as the aesthetics of buildings.

Not only are the sources of architecture’s aesthetics eval-

uated dierently by critics and architects, but also its social

eects. Norman Foster believed that an architect must be

an optimist. In a speech he gave after receiving the Pritzker

Prize, he said his oce had always tried to ask the right

questions with insatiable curiosity and believed in social

context – that buildings are created by people and their

needs (Foster 1999, 1, 2), both material and spiritual. He

devoted the last paragraph to the responsibilities and chal-

lenges faced by architects. Jencks, however, considers high-

tech architecture as performed by Foster, seen as an end

in itself, to be nihilistic, while stressing that the architect

himself do not recognize this (Jencks 1994, 261). The ar-

mation of technique for its own sake leads to emptiness and

meaninglessness. Jencks claims the architecture profession

as a whole seems to have missed this. Increasing warnings

about the dangers caused by the impact of technological de-

vices on society show that it was probably Jencks, a critic

with a broader view of civilization, who was able to make

a more accurate simulation of the future.

Correctly understanding one’s actions can also be disas-

trous for an artist. According to Gołaszewska, structuring

reality binds us: later, it is not we who use our thoughts,

but they subjugate our lives (1984, 23). The same may be

true of the analytical texts of authors who, from the mo-

ment they announce their credo, refuse to deny it. Francis

Edward Sparshott believes that if artists describe their own

mannerism, they themselves risk over-intellectualizing their

artistic activity (Morawski 1973, 18). In order not to betray

their own “manifesto”, the architect can adapt the solutions

they create intuitively under a previously written doctrine.

This situation can result from a new look at the work when

it is completed (Gołaszewska 1986, 181). When it does not

require work from the artist, it becomes a dierent object

than before – a work that is, as it were, alien, further from

personal involvement.

For the creator, becoming aware of the creative processes

can be downright harmful. It is mainly the work that ex-

presses the artist’s views, but, as Potocka vividly described

it, […] it is a witness […] most often outlandish and, in

addition, very imprecise in his testimony (2007, 157). What

problem for the researcher arises from this? Well, just as

an artist adapts a work to earlier guidelines, they can bend

later guidelines to them. Content written after one text gains

popularity can be rebuilt along its lines. However, such sit-

uations are very dicult to detect.

4. An architect can use argumentation in a dishonest way.

It is an exceptional situation when an architect does not

act decently. Their argument is deliberately disingenuous be-

cause it increases the chances of success. Such a description

is no longer a professional explanation and turns into persua-

sion using manipulation. In each of the examples cited be-

low, without being sure of the creator’s bad intentions, only

the creator’s opinion was confronted with that of the critic.

In the modern world, as market mechanisms take over

increasingly more areas of life, art has also become a large-

scale stock market. Like any commodity for sale, it has re-

ceived extremely eective advertising. Myths are growing

around works of art to change the perception of the object

– from mediocre to a masterpiece of genius. Michael Bald-

win even says that modern art is more a result of the dis-

course on it than the creation of its artists, whom he harshly

calls vulgar (Cottington 2017, 69). Therefore, it is natural

that artists try to raise the price of their works with their own

image and statements.

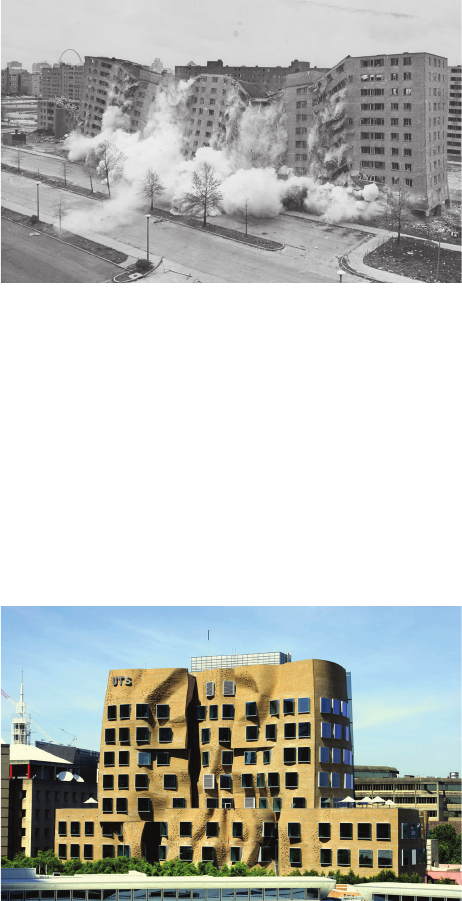

Such a phenomenon also occurs in the case of architec-

ture – an art that requires winning the favor of a wealthy

investor to get a project built. Many architects’ explanations

of their concepts are closer to persuasion than translation.

They are trying to convince an alleged thought process,

which is very questionable upon further reection. Tom

Dyck ho accuses Daniel Libeskind of making his state-

ments about architecture seem like random thoughts pasted

together post factum (Dyckho 2018, 324). The architect ex-

plained the Graduation School building in London (Fig. 5)

as inspired by the constellation Orion, which appeared to

him above the plot of land intended for the building, but he

also said bluntly that he did not want to make a big deal out

of it (Dyckho 2018, 324). Hearing about this correlation

prompts the thought of an absurd “logic” by which one tries

to put incompatible elements of reality together – instead of

intellectual satisfaction, a sense of interacting with some-

thing original, something that is obvious but required the

intervention of a genius to make it appear to us. It is worth