Prothyron from the Villa of Theseus 29

Streszczenie

Prothyron z Willi Tezeusza w Nea Paphos na Cyprze

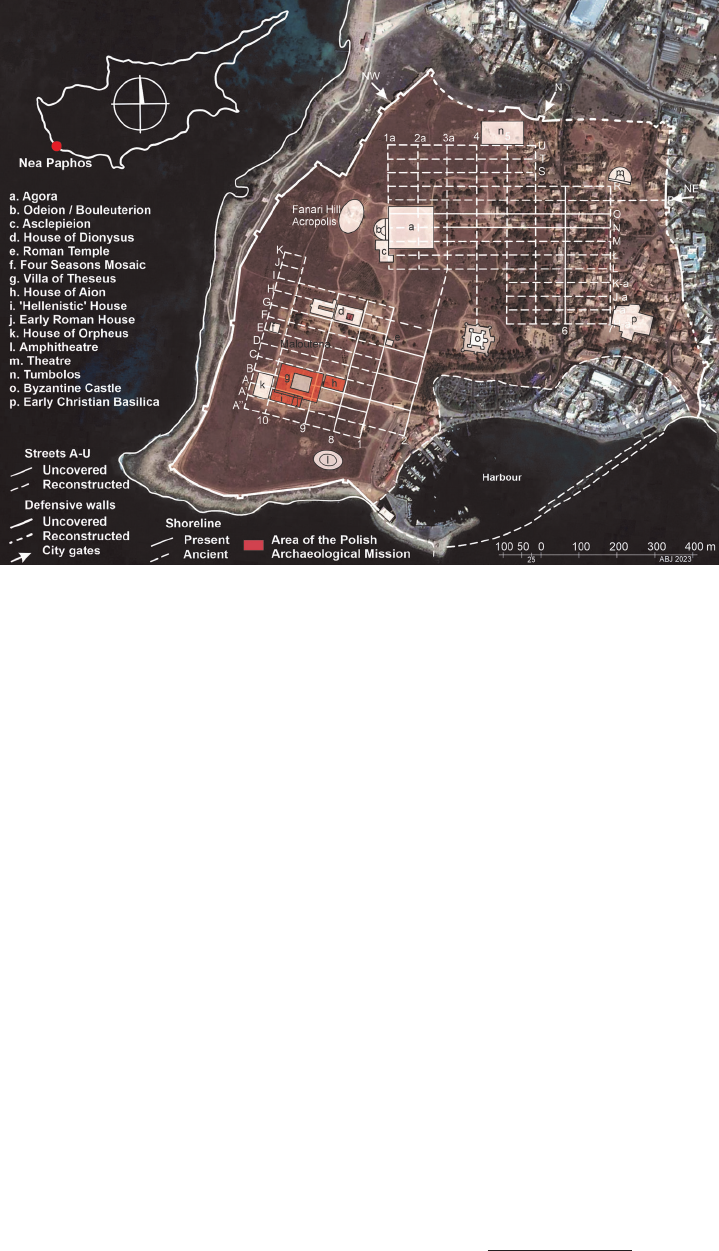

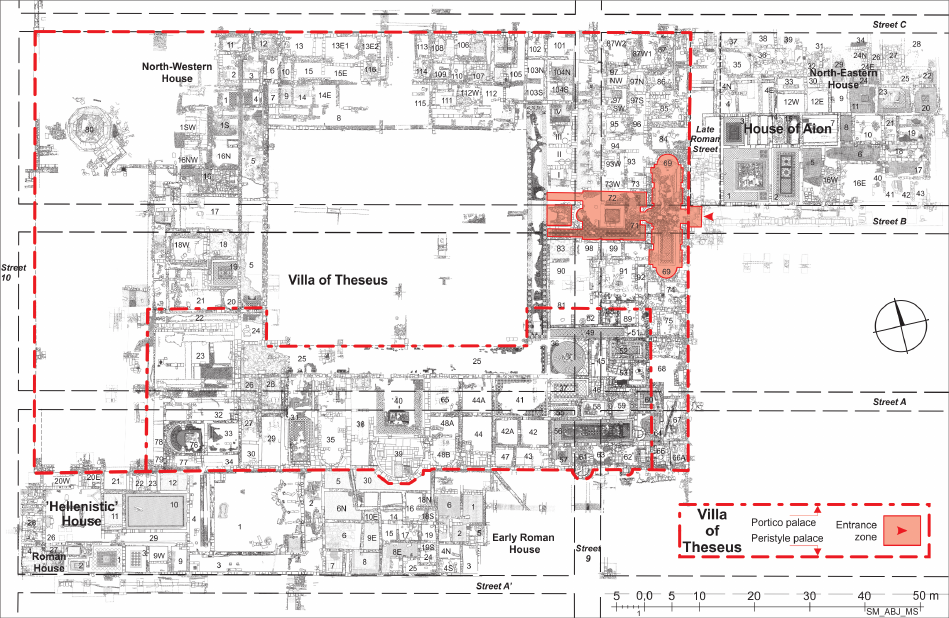

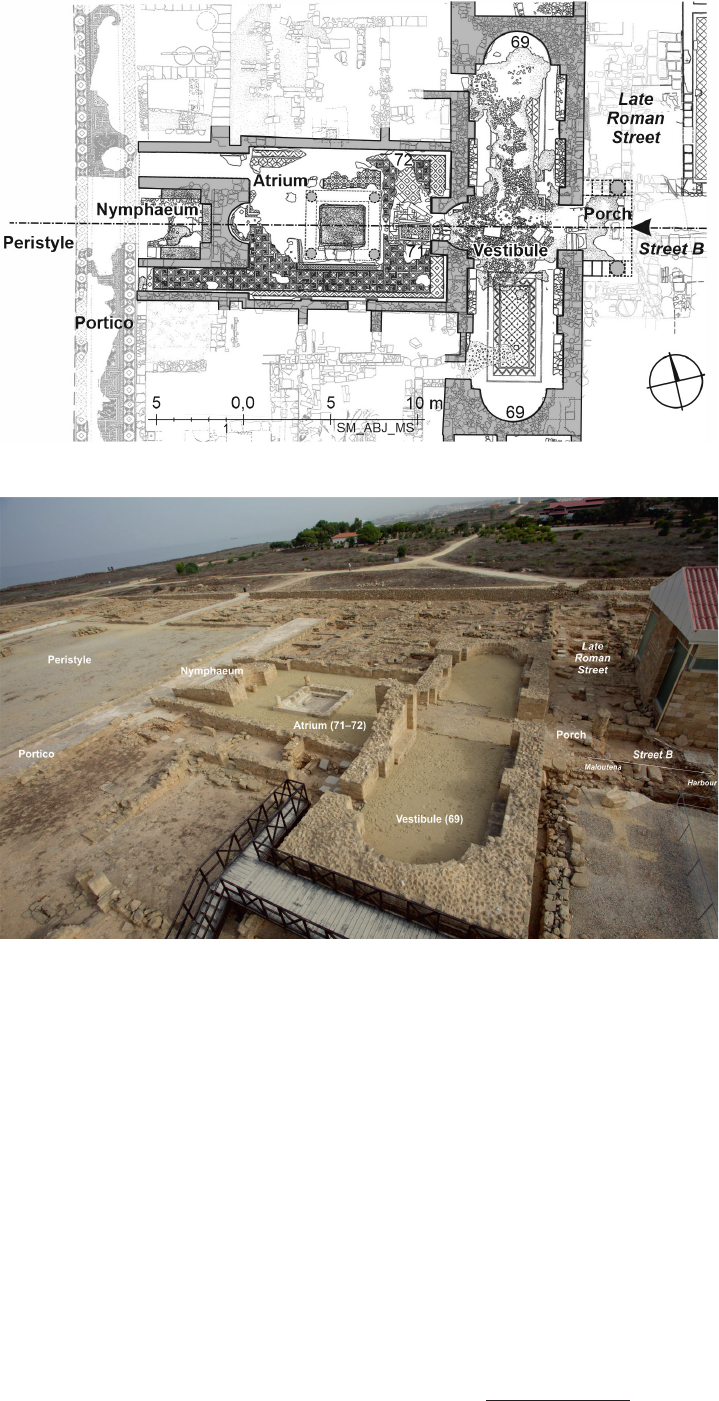

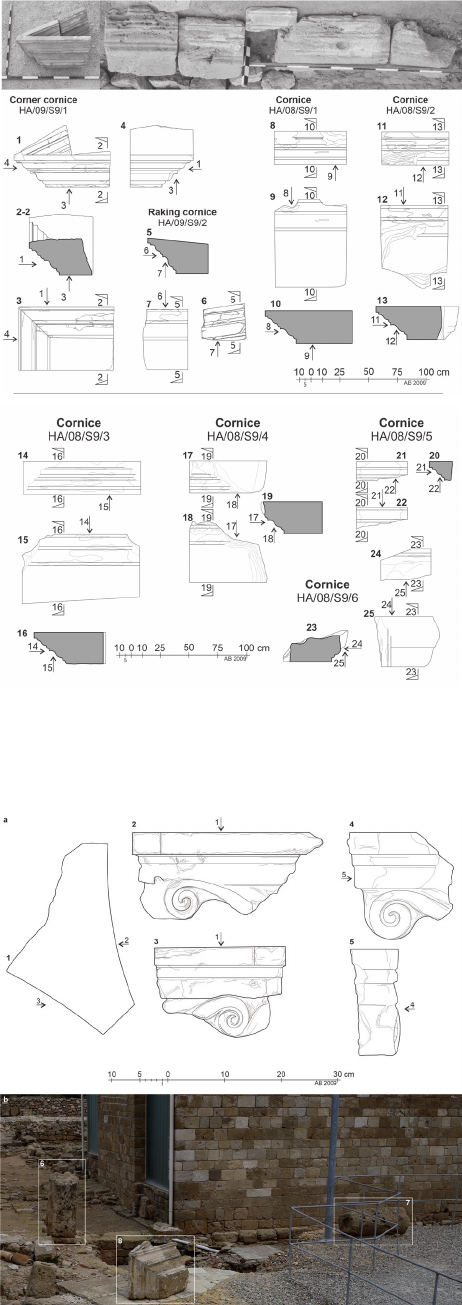

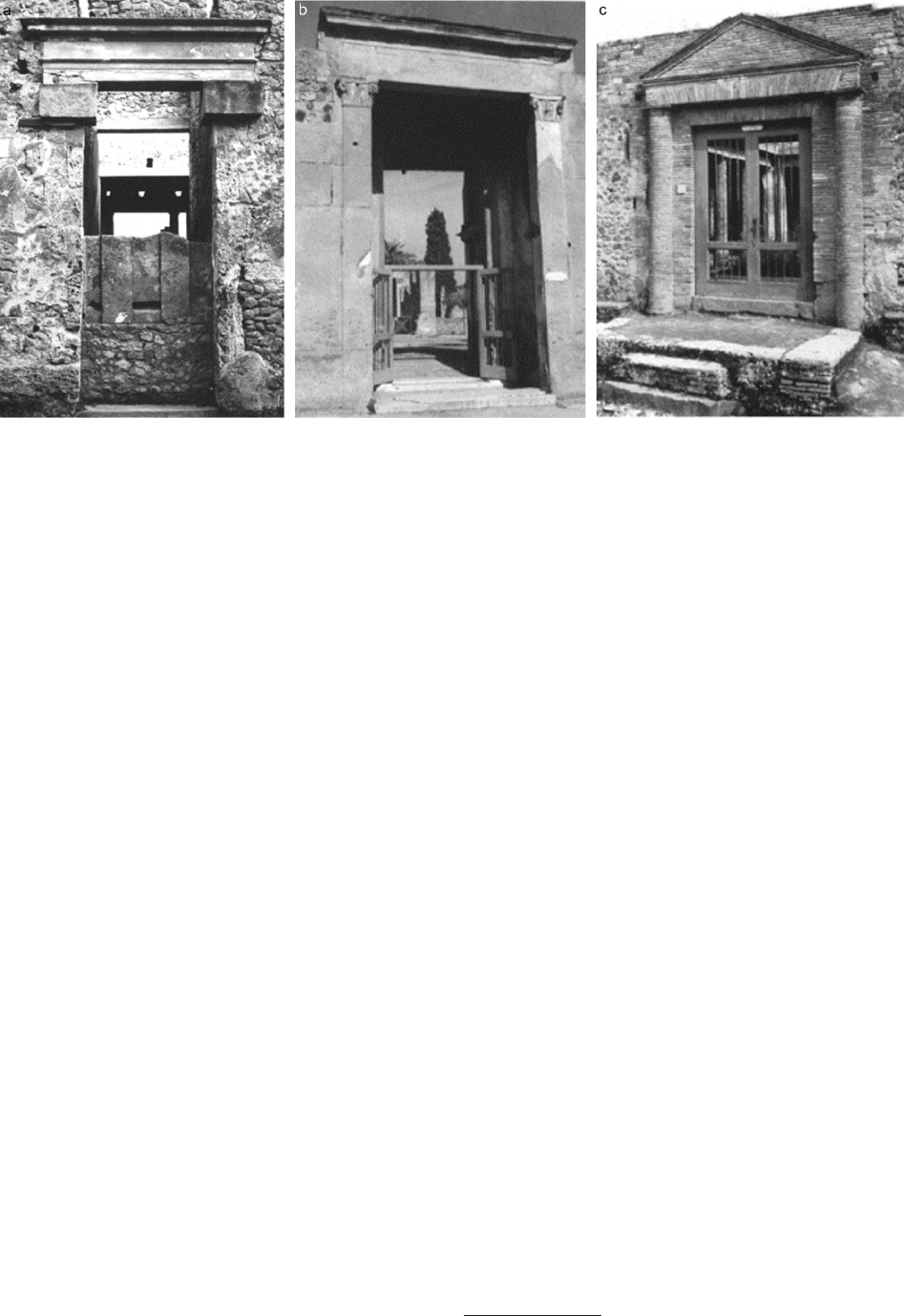

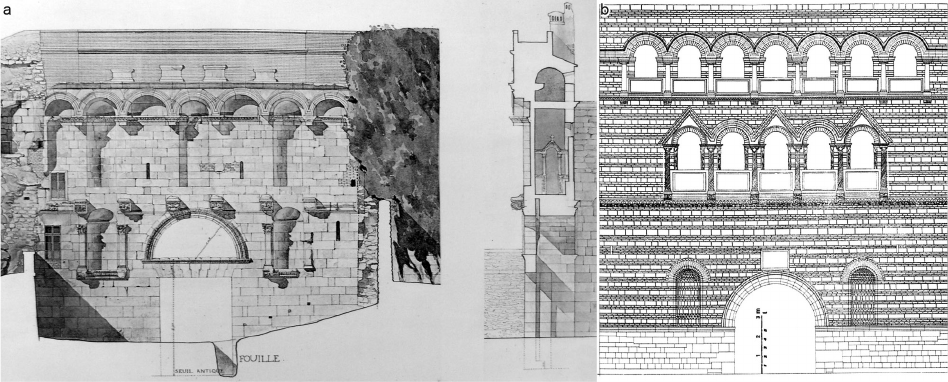

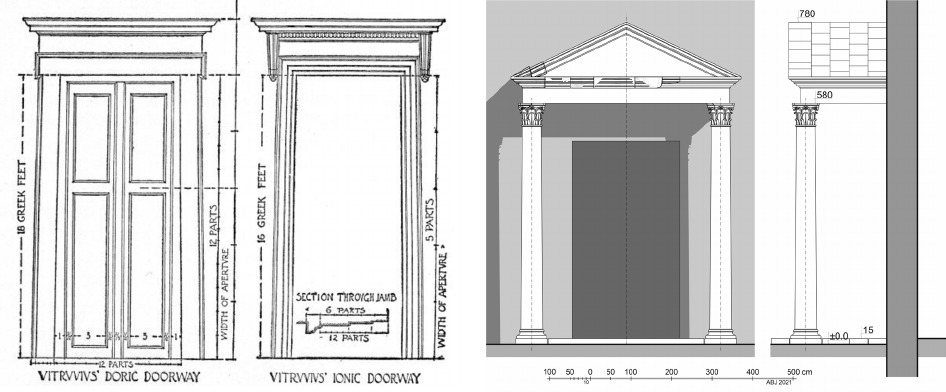

Celem artykułu jest przedstawienie rekonstrukcji monumentalnej bramy prowadzącej do Willi Tezeusza, rzymskiego pałacu znajdującego się

w Nea Pafos na Cyprze. Podczas wykopalisk prowadzonych w pobliżu głównego wejścia do rezydencji odkryto zestaw fragmentów detalu architek-

tonicznego, m.in. kolumn oraz gzymsu. Analiza dekoracji architektonicznej, reliktów wejścia do pałacu in situ oraz analogicznych rozwiązań stoso-

wanych w rezydencjach rzymskich pozwoliła zaproponować rekonstrukcję monumentalnej bramy prowadzącej do złożonego kompleksu wejścio-

wego pałacu. Prawdopodobnie zaprojektowano ją w postaci szerokich drzwi poprzedzonych dwukolumnowym portykiem zwieńczonym trójkątnym

naczółkiem z tympanonem. Jest to forma, którą Witruwiusz nazwał prothyron.

Słowa kluczowe: Nea Pafos, Willa Tezeusza, wejście, prothyron

[11] Brzozowska-Jawornicka A., “The architectural orders and decora-

tion of the “Hellenistic’ House”, [in:] C. Balandier, D. Michaeli-

des, E. Raptou (eds.), Nea Paphos and Western Cyprus, Actes du

conférence Nea Paphos and Western Cyprus, Paphos, 11

th

–15

th

October 2017, Bordeaux forthcoming.

[12] Meyza H., Romaniuk M.M., Więch M., “Nea Paphos. Season 2014

and 2016”, Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean (Research

2014–2016) 2017, no 26/1, 397–418.

[13] Hales S., The Roman House and Social Identity, Cambridge 2003.

[14] Brzozowska-Jawornicka A., “Architecture of the Ocial Spaces

of Selected Residences in Nea Paphos, Cyprus”, Światowit 2019,

nr LVIII, 87–105.

[15] Daszewski W.A., Meyza H. (eds.), Cypr w badaniach polskich,

Materiały z Sesji Naukowej zorganizowanej przez Centrum Ar-

cheologii Śródziemnomorskiej UW im. prof. K. Michałowskiego,

Warszawa, 24–25 luty 1995, Warszawa 1998.

[16] Adam J.-P., Roman Building. Materials and Techniques, Routledge

London and New York 2010.

[17] Vitruvius, De architectura. The Ten Books on Architecture, transl.

M.H. Morgan, Oxford 1914.

[18] Grossman P., “Architectural Elements of Churches, Prothyron”,

[in:] A. Suryal Atiya (ed.), The Coptic encyclopedia, New York

1991, https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/224, ac-

cessed 24.04.2021.

[19] Majcherek G., “Alexandria: Kom El-Dikka Excavations 1997”,

Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 1998, no. 9, 23–36.

[20] Cambi N., Kiparstvo rimske Dalmacije, Split 2005.

[21] McNally S., The Architectural Ornament of Diocletian’s Palace

at Split, British Archaeological Reports International Series 639,

Oxford 1996.

[22] Nikšić G., “The restoration of Diocletian’s Palace – Mausoleum,

Temple, and Porta Aurea (with the analysis of the original archi-

tectural design)”, [in:] A. Demandt, A. Goltz, H. Schlange-Schö-

ningen (eds.), Diokletian und die Tetrarchie. Aspekte einer Zeiten-

wende. Millenium-Stud. Kultur u. Gesch.Ersten Jts. n.Chr., Vol. 1,

Berlin–New York 2004, 163–171.

[23] Nikšić G., “Diocletian’s Palace – design and construction”, [in:]

G. v. Bülow, H. Zabehlicky (eds.), Bruckneudorf und Gamzigrad.

Spätantike Paläste Und Großvillen im Donau-Raum, Bonn 2011,

187–202.

[24] Breitner G., “Die Bauornamentic von Felix Romuliana/Gamzi-

grad und das Tetrarchische Bauprogramm”, [in:] G. v. Bülow,

H. Zabehlicky (eds.), Bruckneudorf und Gamzigrad. Spätantike

Paläste und Großvillen im Donau-Raum, Bonn 2011, 143–152.

[25] Čanak-Medić M., Гамзиград, касноантичка палата. Архитектура

и просторни склоп (résumé: Gamzigrad, palais bas-antique. Archi-

tecture et sa structuration), Saopštenja 11, Belgrade 1978.

[26] Ćurčić S., “Late-Antique palaces: the meaning of urban context”,

Ars Orientalis 1993, nr 23, 67–90.

[27] Brzozowska-Jawornicka A., “Reconstruction of a façade decora-

tion on the House of Aion, Nea Paphos, Cyprus”, “Studies in An-

cient Art and Civilization“ 2016, nr 20, 151–166, pls. 1–6.

[28] Daszewski apud Hadjisavvas S., “Chronique des fouilles et déco-

uvertes archéologiques à Chypre en 1997”, “Bulletin du Corre-

spondance“ Hellénique 1998, no. 122.2, 663–703.

[29] Daszewski W.A., “Nea Paphos: excavations 1998”, Polish Archa-

eology in the Mediterranean 1999, no. 10, 172–173, Fig.10.

[30] Balty J., “Iconographie et réaction paienne”, [in:] J. Balty, Mosa-

iques antiques du Proche-Orient, Paris 1995, 275–289.

[31] Bowersock G.W., Hellenism in Late Antiquity, Ann Arbor 1990,

49–53.

[32] Daszewski W.A., Dionysos der Erlöser. Griechische Mythen im

spätantiken Cypern, Mainz am Rhein 1985.

[33] Deckers J.G., “Dionysos der Erlöser? Bemerkungen zur Deutung der

Bodenmosaiken im <Haus des Aion> in Nea-Paphos auf Cypern

durch W.A. Daszewski”, Römische Quartalschrift für Christliche

Altertumskunde und Kirchengeschichte 1986, no. 81, 145–172.

[34] Kessler-Dimin E., “Tradition and transition. Hermes Kourotrophos

in Nea Paphos”, [in:] G. Gardner, K.L. Osterloh (eds,), Antiquity

in Antiquity. Jewish and Christian Pasts in the Greco-Roman

World, Tübingen 2008, 255–281.

[35] Ladouceur J., “Christians and pagans in Roman Nea Paphos: con-

textualizing the ‘House of Aion’ mosaic”, UCLA Historical Jour-

nal 2018, nr 29(1), 49–64.

[36] Mikocka J., “The Late Roman Insula in Nea Paphos in the light of

new research”, Athens Journal of History 2018, no. 4 (2), 117–134.

[37] Olszewski M.T., “L’allégorie, les mystères dionysiaques et la mo-

saïque de la Maison d’Aiôn de Nea Paphos à Chypre”, Bulletin de

l’Association Internationale pour l’Étude de la Mosaïque Antique

1990–1991, nr 13, 444–463.

[38] Olszewski M.T., “The iconographic programme of the Cyprus mo-

saic from the House of Aion reinterpreted as an anti-Christian pole-

mic”, [in:] W. Dobrowolski (ed.), Et in Arcadia ego. Studia memo-

riae Professoris Thomae Mikocki dicata, Varsoviae 2013, 207–239.

[39] Quet M.-H., “La mosaïque dite d’Aiôn et les Chronoi d’Antioche”,

[in:] M.-H. Quet (ed.), La ‘crise’ de l’Empire romain de Marc Au-

rèle à Constantin, Paris 2006, 511–590.

[40] Jastrzębowska E., “Wall paintings from the House of Aion at Nea

Paphos”, Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 27/1, 2018,

527–597, DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0013.2015.

[41] Jastrzębowska E., “Mosaics in the House of Aion: A small con-

tribution to a big problem”, [in:] H. Meyza (ed.), Decoration of

Hellenistic and Roman Buildings in Cyprus, Harrassowitz Verlag,

Warsaw–Wiesbaden 2020, 95–103.

[42] Jastrzębowska E., “The House of Aion in Nea Paphos: seat of an

artistic synodos?”, Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 2021,

nr 30/2, 339–386, DOI: 10.31338/uw.2083-537X.pam30.2.13.

[43] Brzozowska-Jawornicka A., “Reconstruction of the Western Co-

urtyard of the ‘Hellenistic House’ in Nea Paphos, Cyprus”, [in:]

G. Bąkowska-Czerner, R. Czerner (eds.), Greco-Roman Cities at

the Crossroads of Cultures, ArchaeoPress, Oxford 2019, 57–73.

[44] Meyza H., Nea Paphos V. Cypriot Red Slip Ware. Studies on a Late

Roman Levantine ne ware, Varsovie 2007.

[45] Czerner R., The Architectural Decoration of Marina el-Alamein.

British Archaeological Reports International Series 639, Oxford

2009.

[46] Pesce G., Il Palazzo delle colonne in Tolemaide di Cirenaica,

Roma 1950.

[47] Hébrard E., Zeiller J., Spalato. Le palais de Dioclétien, Paris 1912.