122 Beata Malinowska-Petelenz, Anna Petelenz, Magdalena Jagiełło-Kowalczyk, Małgorzata Petelenz, Radosław Rybkowski

Rodriguez and Coronado 2014). The starting point was

to identify the roadside architecture of Route 66, the fea-

tures constitutive of areas adjacent to US highways, and

its compliance (or non-compliance) with UN Sustainable

Development Goals no. 3 and 11: “Good health and qual-

ity of life” and “Sustainable cities and communities”. The

road as an essential and constitutive element of American

culture has its visual and spatial manifestation in roadside

architecture (United Nations 2022).

Research assumptions

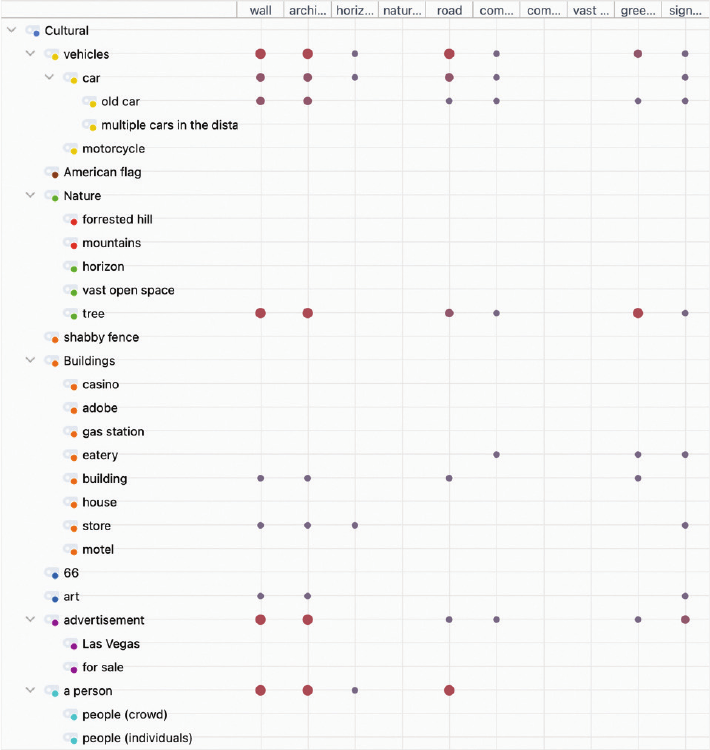

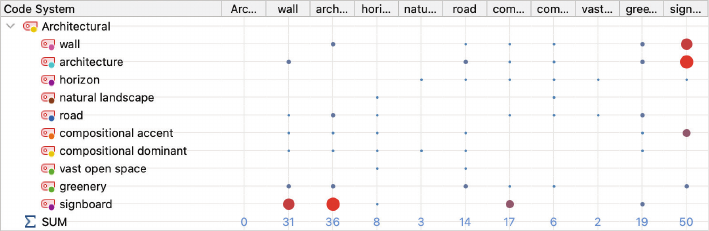

Qualitative research in architecture requires a clear and

precise denition of the research procedure so that the re-

sults can be intersubjectively veried. It is in qualitative re-

search, where the researcher and their subjective approach

plays a key role, that the procedure gains signicance. This

is because it is important that the results do not become

merely a record of individual impressions. As Uwe Flick

emphasises: […] You should try to make the design of your

research and the methods as explicit and clear, and with as

much detail, as possible (Flick 2007, 114). In the context

of the subject under study, we assumed that the main user

of Route 66 was a viewer that moves fast (by car), and the

genius loci of the area stems from experiences and per-

ceptions created by scattered architectural structures that

blend into the landscape context. The visual method was

chosen as the most appropriate to identify the factors that

determine the distinctive atmosphere that results from the

architectural and landscape conditions along the road.

Of all the arts, architecture has the greatest impact on

nature, the landscape, the human environment and thus

determines an individual’s wellbeing and the life of a com-

munity. It is also sometimes seen as a purely sculptural or

visual art. Simon Unwin (2019) proposes that the concept

of extra-linguistic metaphor – a visual metaphor related to

user experience – should be introduced to its study.

If architecture can be a metaphor, it expects an audience

capable of deciphering it and understanding its meaning.

While some disciplines ignore the importance of the visual,

[…] cultural studies has always assumed an analysis of the

visual […]. [It] is concerned with “how culture is produced,

enacted and consumed”, so it is unavoidable that scholars

working in this eld will focus on visual issues (Pink 2008,

128). We proposed a carefully designed three-step method.

Method and procedure

John W. Creswell (2013) in his fundamental textbook

Re search Design. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Me -

thods

Approaches, clearly indicates that sound work by

a researcher who uses qualitative methods must include

the following steps:

1) data collection/documentation, during which the

author […] should identify what data the researcher will

record and the procedures for recording data (Creswell

2009, 181),

2) interpreting data, or transforming data into informa-

tion – which involves […] making sense out of text and

image data (Creswell 2009, 183),

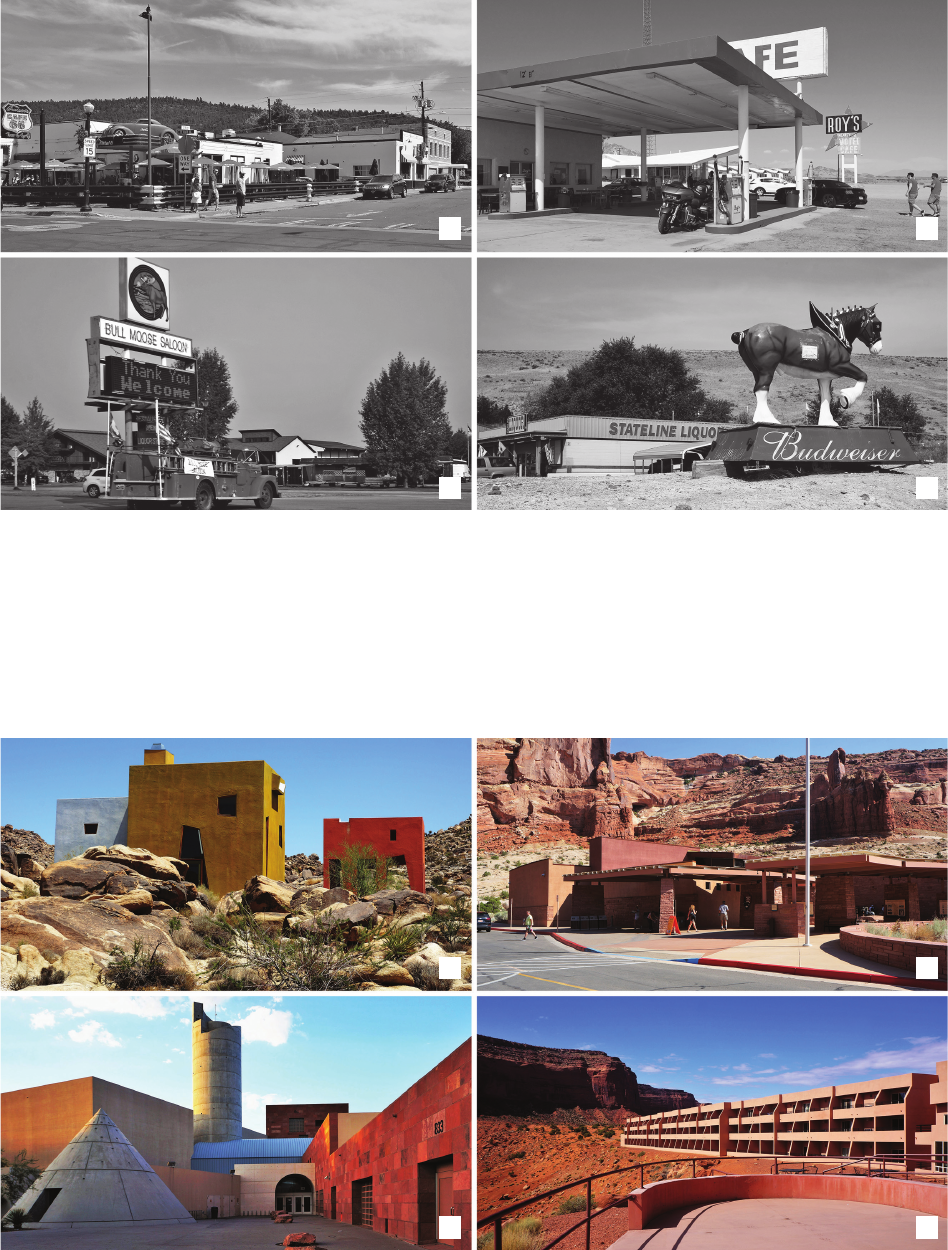

attracted small and larger businesses. The most important

change was not just economic – it went much deeper.

Symbolically and physically, the highway, together with

its accompanying commercial services for travellers, be-

came the newest and most inuential landscape in 20

th

-cen-

tury America. The automotive world: the highways, the

drivers and passengers of cars, trucks, buses and motorcy-

cles – created a new way of expressing the Ame rican life-

style – the freedom and passion to move and travel, whether

for work

or recreation (Jakle, Sculle 2004). Trains and rail-

ways, dominant in the late 19

th

and early 20

th

centuries, did

not provide the kind of independence that Americans found

in cars. From the beginning, they associated them with ev-

erything the railway was not. Private, rather than owned by

a large company, independent of a timetable, the car was

understood as a vehicle for escaping into adventure (Nye

2011, 104). Travelling by car was reminiscent of the days

of the pioneers. Jean Baudrillard (2011) also wrote about

viewing reality from the windows of a speeding car in his

famous manifesto America.

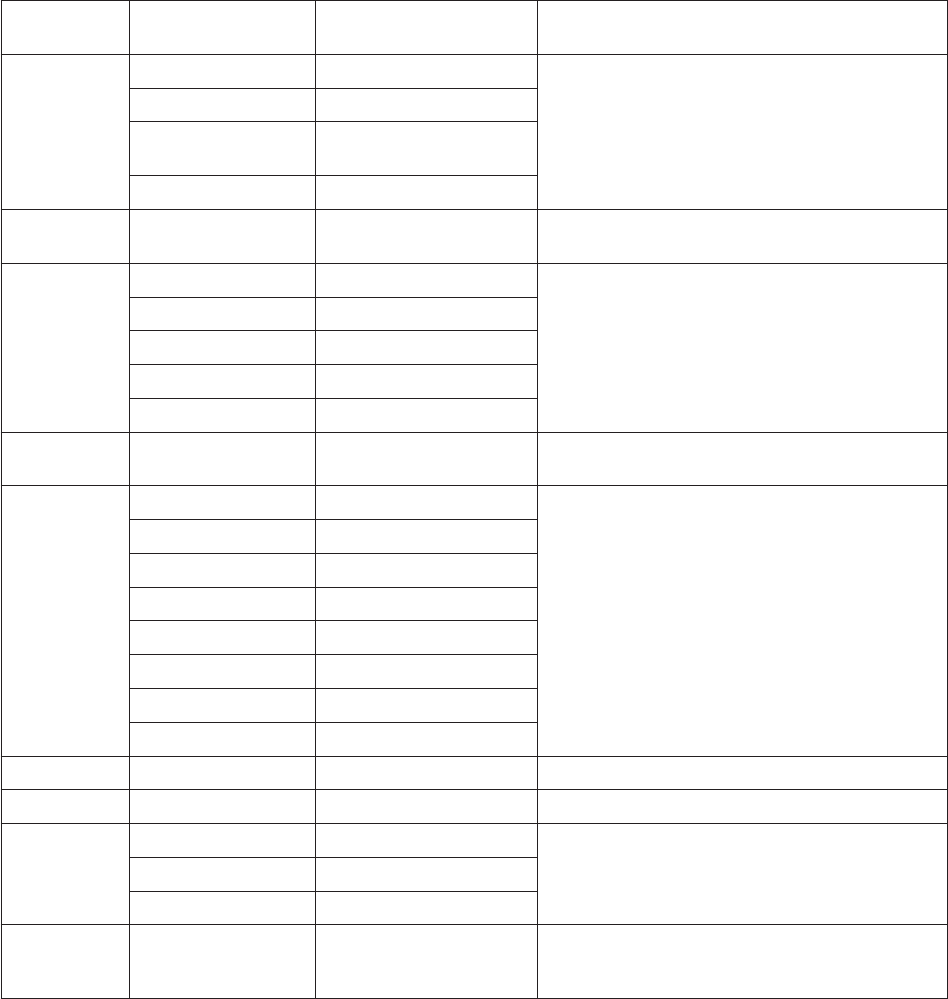

Route 66

– architectural context

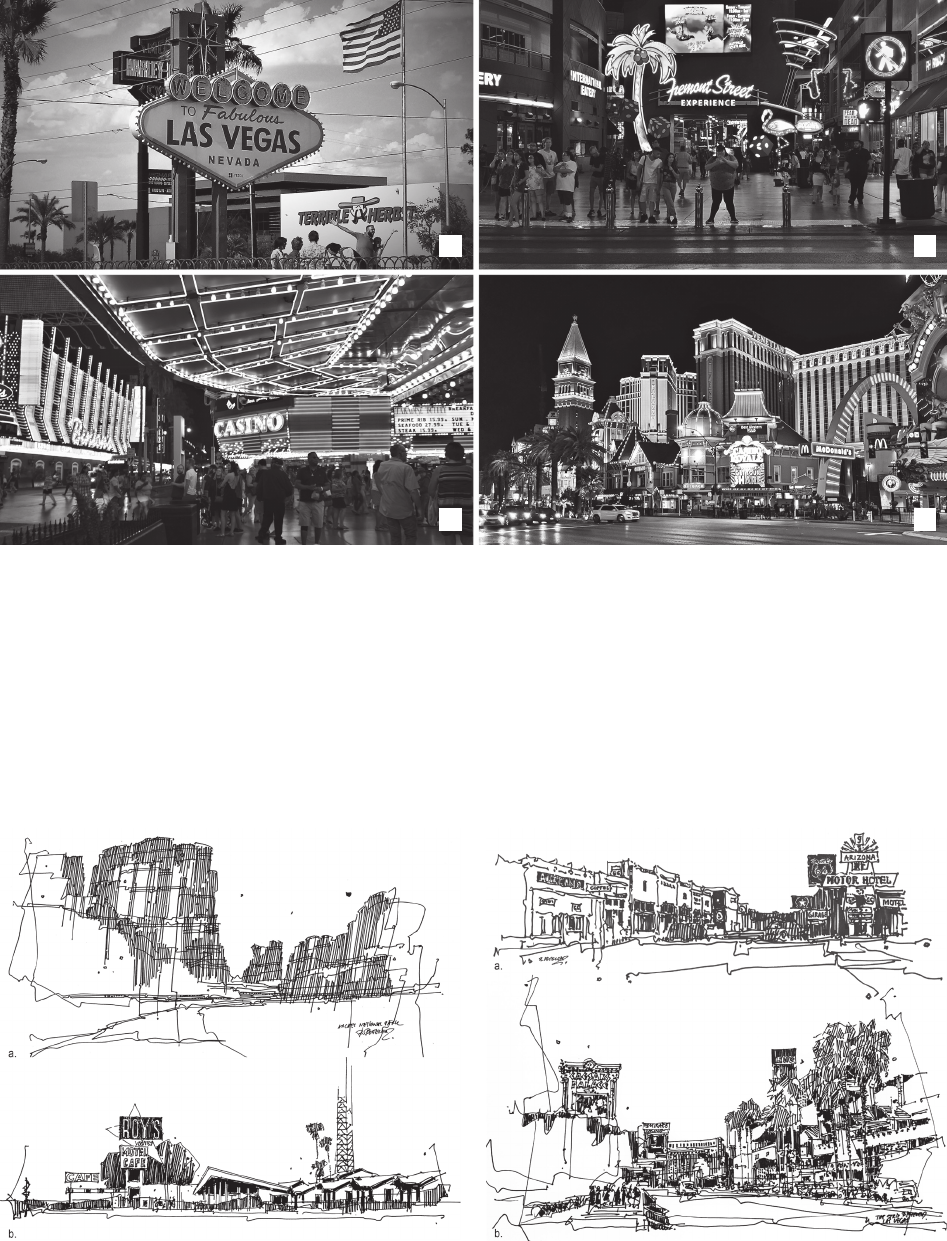

Architecture is created at the intersection of engineer-

ing, construction and technology as well as art, creativity

and sometimes fashion. It must also answer societal needs

and aspirations, and should serve the well-being of indi-

viduals and groups, which is why it always reects the so-

cial and cultural context. The dynamism of local American

architecture calls for innovative modes of research that are

open to faster interpretations and reinterpretations (Bau-

man 2006). It also requires a specic perspective – prefer-

ably one from the window of a moving car. Robert Venturi,

Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour (2013) presented

such a discussion of local architecture, and in their man-

ifesto Learning from Las Vegas oered an in-depth anal-

ysis of the titular city, which is an extreme exemplica-

tion of eclectic and functional architecture that abolishes

the rift between function and form, mass and ornament.

Marta Mroczek (2016) presented an insightful analysis of

roadside architecture – she called it auto-architecture. Its

distinctive features found in the desert or in the vicinity

of small settlements have become important landmarks.

Architecture organises space, but this is not all – its

signicance goes beyond the mere structure of organised

space (Whyte 2006). Umberto Eco (1997, 174) noted that

[…] we commonly do experience architecture as commu-

nication, even while recognising its functionality. The way

architecture is interpreted changes with the times, as well

as the dominant culture, so researchers should […] explore

how architecture is interpreted by its users and viewers

(Whyte 2006, 171). Our research on Route 66’s roadside

architecture is an exploration of the architecture itself, but

more importantly it is an analysis of the Polish viewer’s

interpretation of roadside architecture (Diener 2000).

Landscapes of everyday life, such as roadside archi-

tecture, have begun to attract the attention of cultural re-

searchers since the early 1980s (Jackson 1984), but specif-

ic roadside heritage studies are recent and still few (Ruiz,