106 Kees Christiaanse, Joanna Jabłońska

Christiaanse continues to be a Distinguished aliated

professor at TUMünchen. In 2009 he accepted the func-

tion of the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam

(IABR) curator.

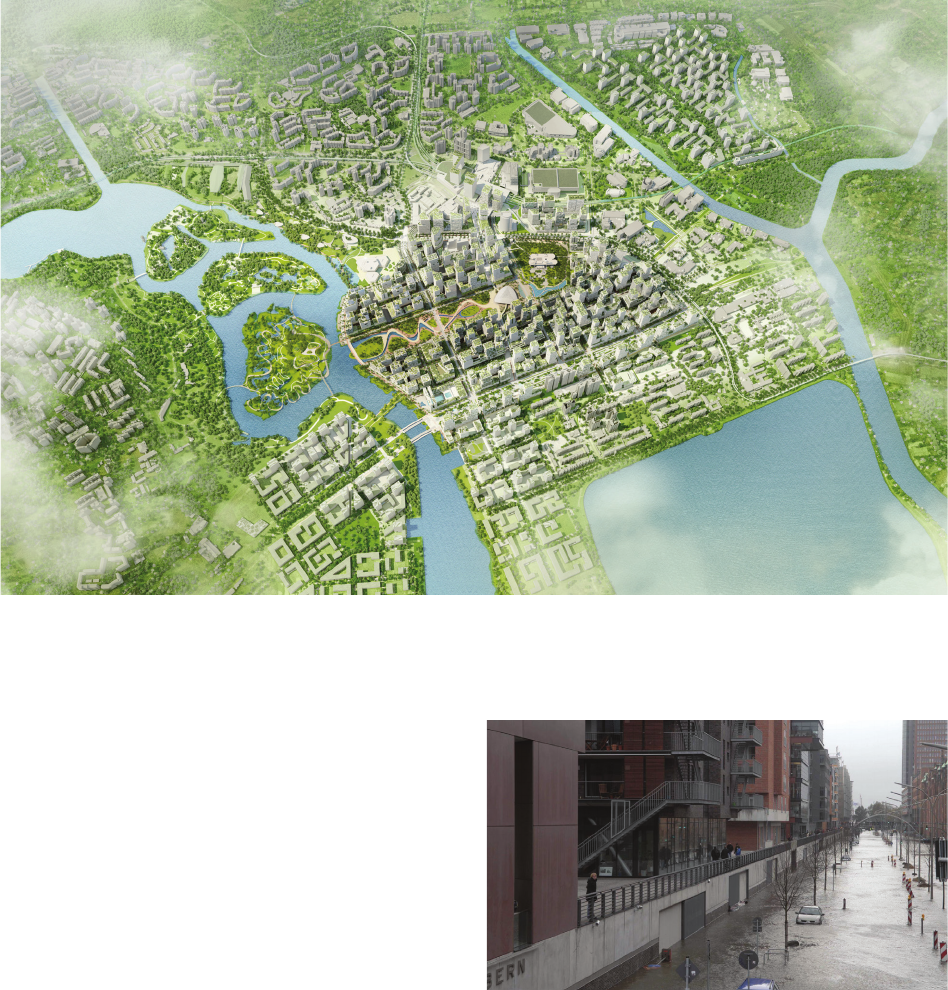

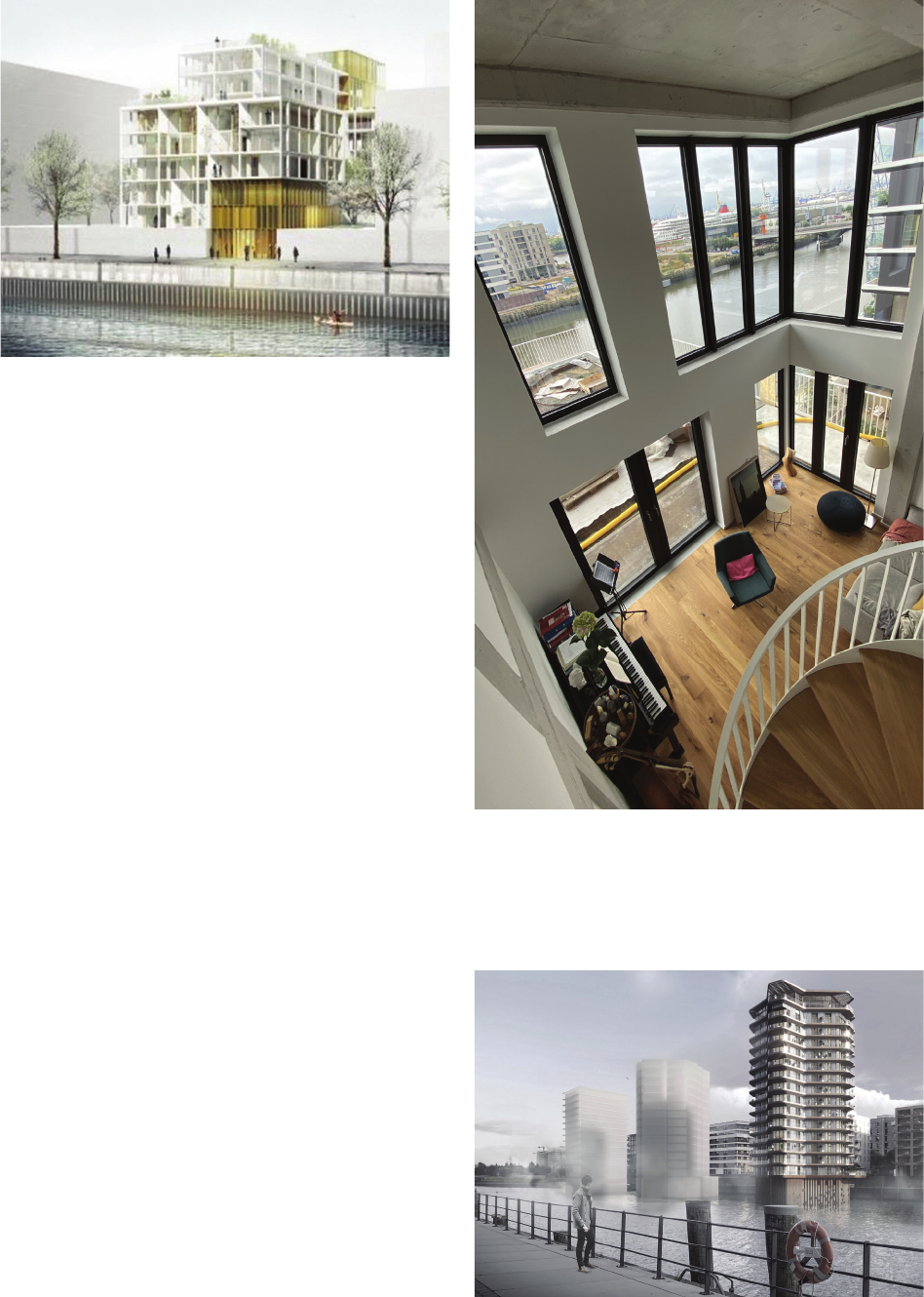

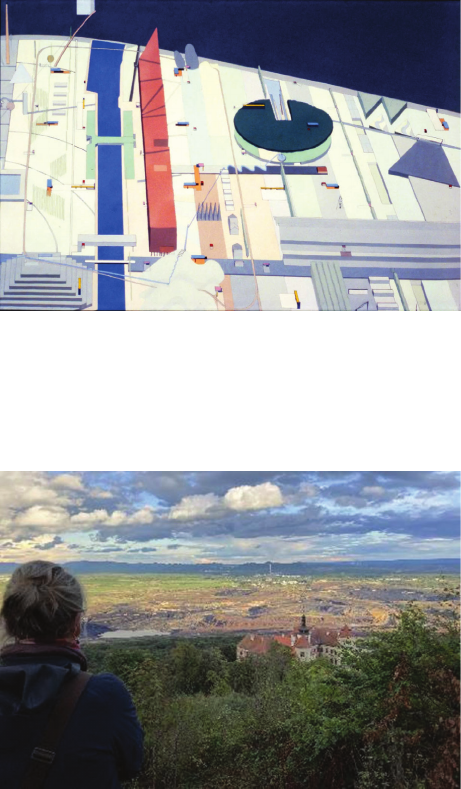

Kees Christiaanse is an author of many architectural

works, and selected examples are as follows: Housing

block K25, The Hague (1989), Housing blocks on Java Is-

land, Amsterdam (1998), Art Academy Rotterdam (1998),

Holzhafen, oces and apartments in Hamburg, Germany

1996(?), The Red Apple, residential high-rise with oces,

Rotterdam (2009), Starsh, an apartment tower in Hafen

City Hamburg, 2021. He is also an urban designer, and here

are selected works: Wijnhaven Island Rotterdam 1995,

Masterplan for housing festival, Hague (1987), Urban plan

for Lelystad South area of the Flevoland Vinex (1999),

HafenCity in Hamburg (winning proposal – 1999), 2012

Summer Olympic Legacy Masterplan [4], [5], Masterplan

for Jurong Lake District, Singapore’s new-highspeed rail-

way station quarter (2015–2018) (Figs. 1–14). Professor

is also a book author, of which examples are as listed:

Situation KCAP [6], The Potato Collection [7], Textbook

[3], The Grand Projet [8], The City as Loft [9], Open City

[10], Campus and the City [11], The Strip [12].

When asked about his inspirations, Christiaanse ex-

plains: I am both inspired by the dierent exponents of

modernism, and by the more rich predecessors and later

soft modernisms, like by Adolf Loos, Duiker, Schindler,

Neutra. In urban design Henry Sauvage, August Perret,

Berlage, Bruno Taut, Ildefonso Cerda… I have too many

idols. But I am especially inspired by people like Jane

Jacobs, Patrick Geddes… [1], [2].

The pandemic

In Professor Kees Christiaanse’s work, social interac-

tion constitutes a crucial pivot around which urban design

revolves. The recent pandemic had quite some impact on

human activities in urban spaces. The role of the home of-

ce became very important, which inuenced how people

moved around the city and related to their home environ-

ment. Since the pandemic awed and people did not com-

pletely return to their oces and schools, the discourse

of whether remote working and learning is ecient and

should partly stay is running, also taking into account the

psychological problems of lack of social encounter. We

estimate that it will remain a constant element in modern

working culture. At KCAP, his architecture rm, remote

working is planned to be max. 20–30% of regular work-

ing hours. To summarize, remote working will require

quality home-oce and co-working spaces in residential

neighbourhoods and parallel to that an increase in demand

for local daily care amenities. On the other hand, it will

change the size and organization of oces, schools and

other institutions as focused places of encounter.

Another aspect is Internet shopping, which generates

a fundamental change in the retail landscape. Large-scale

storage and distribution hubs in peripheral sites create new

centralities with outlet developments and entertainment.

These complexes inuence the position of city centres and

make them look for a viable programmatic alternative.

Meanwhile, the Internet has a far-reaching impact on

mobility systems. Innumerable apps allow access to a va-

riety of bike-and car-sharing systems, public transport and

other modes, which also oer multi-mode travel menus in

order to get as fast to a destination as possible. For exam-

ple, e-bikes bring more people on bicycles than before, es-

pecially in cities with intensely dierentiated topography.

These developments can be evaluated as positive.

However, they do not necessarily inuence the physical

urban neighbourhood in a signicant way, while peripher-

al sites, industrial compounds and shopping centres may

intensively transform by the impact of logistics and data

centres. On the contrary, the well-known concept of the

15-minutes city has become more important through the

pandemic, as people started to avoid public transporta-

tion and large centres, causing neighbourhood shops and

amenities to ourish [1], [2]. The third aspect of the pan-

demic is the consolidation of suburbanization and the use

of cars. While a part of people was able to enjoy already

existing services in their area, others started to use indi-

vidual transportation more often, avoiding personal con-

tact with larger groups. The car experienced a renaissance.

For the same reason, isolated houses in the suburbs sud-

denly became more popular. In the meantime, this phe-

nomenon has been “corrected” by the energy prices and

threatening shortage. Therefore, the trend towards more

compact and dense neighbourhoods and adequate public

transport services will hold on.

Today, social changes are often advancing faster than

politics and legislation. Until 15 years ago, mobility was

the territory of cities’ authorities, for example in construct-

ing a new tram line. Nowadays there are multiple private

and grassroots innovations in mobility systems, which

complement the public oer. The same situation can be

seen in the building regulations concerning sustainability

and zero-emission. Sustainable technology for district en-

ergy systems and self-suciency are available, but legis-

lation is lagging behind. In many countries, maybe except

Switzerland and Singapore, civil servants are underpaid

and tied up in bureaucracy, which causes a brain drain to-

wards private enterprises. This in turn has a slowing eect

on a dynamic and lean political decision-making and leg-

islation culture [1], [2].

Professional title

Before the introduction of the EU legislation, in

Switzer land and the Netherlands, the title “architect” was

not protected, meaning everybody was allowed to make

an architectural design and submit a building permit. On

the other hand, there were eective control mechanisms.

Every city had an aesthetic committee and urban design

panels that evaluated design proposals. In contrast, in

counties like Germany, Poland, England, France or Bel-

gium, the title was always protected. An architect-in-spe

needs to have a recognized diploma, 2 years of practice

and pass an additional practical exam. Interestingly, the

quality of architecture in the respective countries does not

necessarily correspond with these requirements. The ar-

chitecture produced in Switzerland and the Netherlands