126 Krzysztof Mycielski

[1] Klimczak D., Życie i przestrzeń. Grupa 5 Architekci, Grupa 5 Ar-

chitekci, Warszawa 2018.

[2] Leszczyński M., Od demiurga do twórczego koordynatora. Ewolu-

cja warsztatu architekta po 1995 r., PhD thesis, Wydział Architek-

tury Politechniki Gdańskiej, Gdańsk 2022.

[3] Piątek G., Trybuś J., Lukier i mięso, wokół architektury w Polsce po

1989 roku, 40 000 Malarzy, Warszawa 2012.

[4] Trammer H., Strumykowa, “Architektura Murator” 2002, nr 11(98),

20–23.

[5] Bielecki C., Ciągłość w architekturze, “Architektura” 1978, nr 3–4,

26–75.

[6] Stiasny G., Młodzi realistami?, “Architektura Murator” 2003,

nr 9(108), 40.

[7] Ciarkowski B., Non-modern modernity? Neomodern architecture,

“Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts” 2016, Vol. 18, 87–97.

[8] Mycielski K., Do the Bauhaus ideas t into Polish reality of the

21

st

century? The inuence of the works of Walter Gropius and Mies

van der Rohe on contemporary projects on the example of build-

ings designed by Grupa 5 Architekci, “Architectus” 2020, nr 4(64),

61–74, doi: 10.37190/arc200406.

[9] Bauman Z., Ponowoczesność jako źródło cierpień, Wydawnictwo

Sic!, Warszawa 2000.

[10] Solarek K., Współczesne koncepcje rozwoju miasta, “Kwartalnik

Architektury i Urbanistyki” 2011, nr 4(56), 51–71.

[11] Koolhaas R., Śmieciowa przestrzeń, Centrum Architektury, War-

szawa 2017.

[12]

Karta Nowej Urbanistyki, tłum. M.M. Mycielski, G. Buczek, P. Choy-

nowski,

Wydawnictwo Urbanista, Warszawa 2005.

[13] Trybuś J., Wyszpiński P., Książnica-Atlas. Plan Warszawy 1939,

Muzeum Warszawy, Warszawa 2015.

[14] Krier L., Architektura wspólnoty, Słowo/obraz terytoria, Gdańsk

2011.

[15]

Kiciński A., Lekcja romantycznego racjonalizmu Kolonii Lubeckie-

go/Staszica, “Kwartalnik Architektury i Urbanistyki” 2001, nr 2(46),

192–203.

[16] Lewicki J., Roman Feliński: architekt i urbanista, pionier nowo-

czesnej architektury, Wydawnictwo Neriton, Warszawa 2007.

[17]

Feliński R., Miasta, wsie, uzdrowiska w osiedleńczej organizacji kra -

ju z 105 rycinami, Nasza Księgarnia, Związek Nauczycielstwa Pol -

skiego, Warszawa 1935.

[18] Dybczyńska-Bułyszko A., Architektura Warszawy II Rzeczpospoli-

tej, Ocyna Wydawnicza PW, Warszawa 2010.

[19] Środoń M., Konikt wokół problemów zagospodarowania prze-

strzennego – rola internetu jako narzędzia politycznej samoorgani-

zacji społeczności lokalnej. Przypadek Starej Ochoty w Warszawie,

[in:] B. Lewenstein, J. Schindler, R. Skrzypiec (red.), Partycypacja

społeczna i aktywizacja w rozwiązywaniu problemów społeczności

lokalnych, Wydawnictwo UW, Warszawa 2010, 143–163.

References

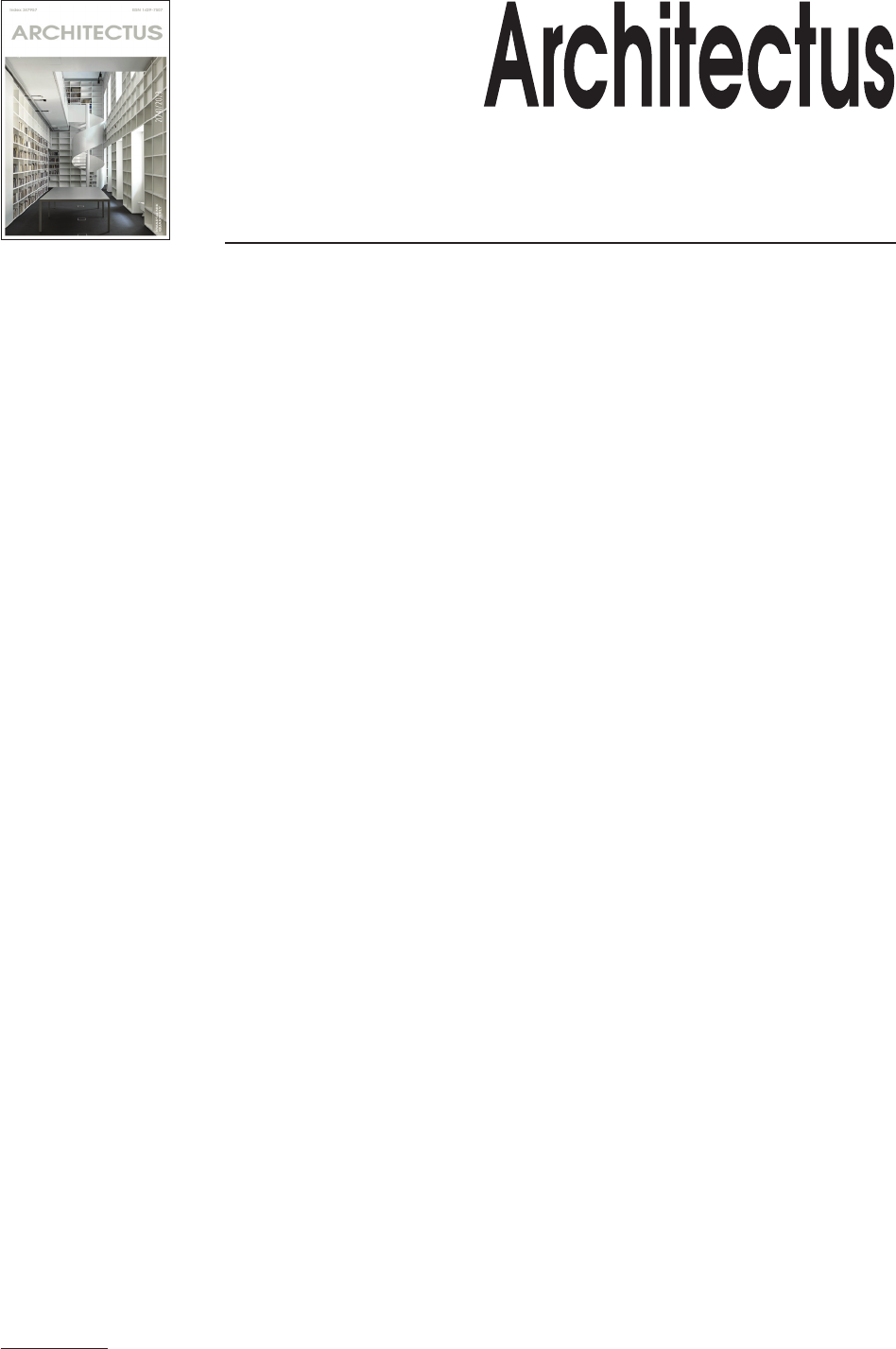

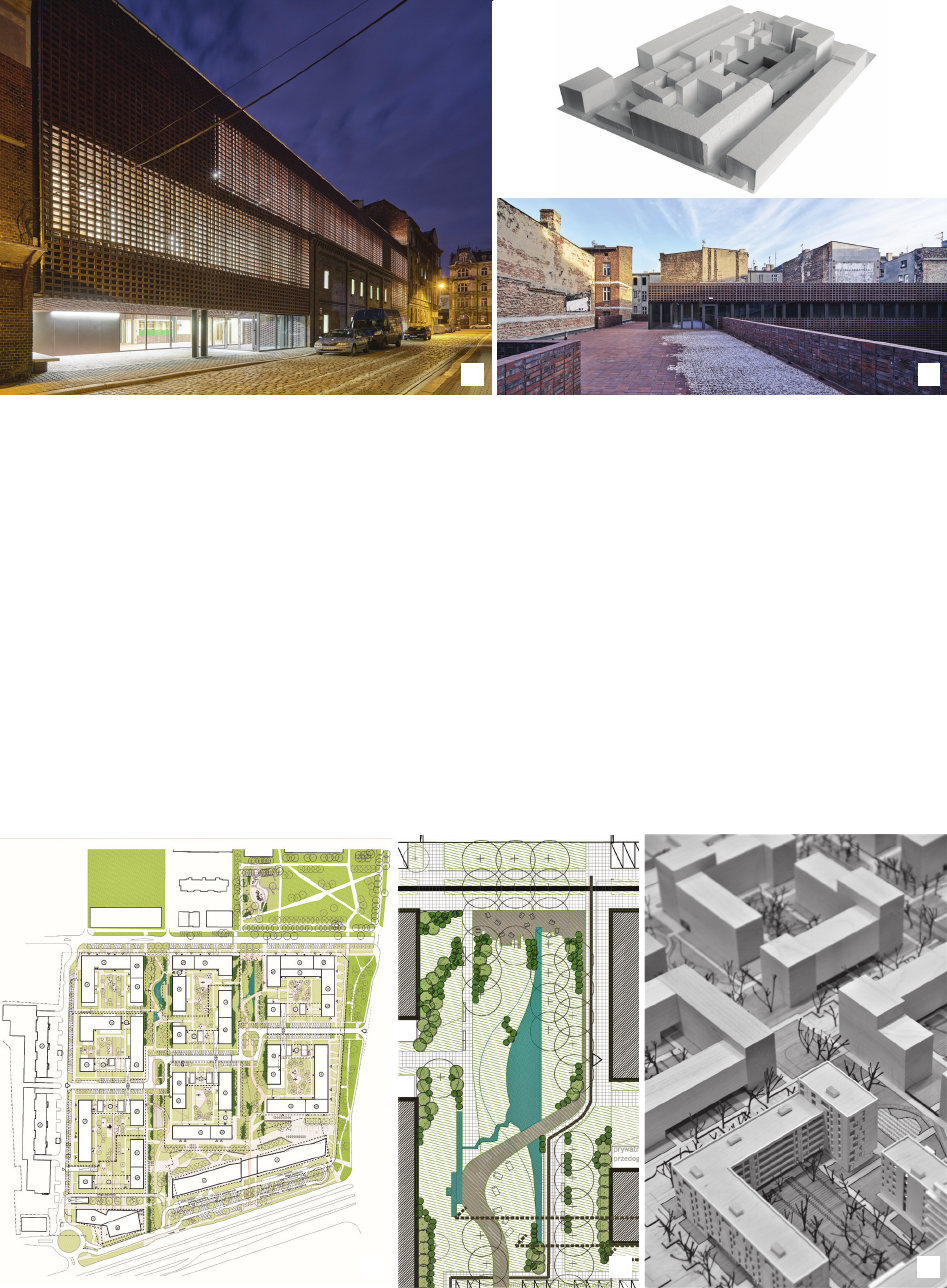

the courtyards with the landscape of public spaces. Accord-

ing to the competition description by Justyna Dzie dziej-

ko, a landscape designer cooperating with the Grupa 5

Architekci studio, […] the concept of “Śródmieś cie Leś-

ne” merges the idea of combining modern architecture and

nature. […] Linear parks have the character of landscape

gardens. […] Courtyards within quarters have a develop-

ment character dierent from linear parks and a more ur-

ban landscape style [24, pp. 14–15].

On the other hand, in the concept of the Nowe Jeziorki

housing estate, the intended advantage of the project was

the layout of the courtyards on real land, not on under-

ground garages, thanks to the location of all housing estate

parking spaces outside the quarters in separately designed

parking buildings. This allowed for the introduction of

high greenery with a park character into the space of the

courtyards.

Distinctive signs for both concepts were natural reten-

tion reservoirs in the form of ponds designed in the public

space. All the above solutions in the eld of landscape

architecture are related to the use of species biodiversi-

ty postulated in the context of climate warming and the

avoidance of the so-called heat islands by increasing the

porosity of the urban tissue.

Summary. Design philosophy

Concentrating on a fragment of our creative search,

in this case regarding the model of quarter development,

I tried to show how spatial solutions, which are most often

the result of a specic architectural task contracted, can

aect the beliefs of designers.

In autumn 2019, architects from Grupa 5 presented their

achievements at a meeting in the Zodiak architecture pa vi-

lion

in Warsaw. For the rst time, they decided to summa-

rize their shared approach to the profession in the form of

several theses, which became a pretext for discussion with

the audience. By referring to them, even in the journalistic

form in which they were written, we can arrive at a sum-

mary of this article as follows:

1. Design is a complex process involving many archi-

tects and engineers with dierent competencies. For this

reason, a modern architectural studio should be based

on perfect partnership cooperation between people. The

strength of such a model is the exchange of ideas, and

above all diversity, which is in contradiction with the star

image of the architect promoted by the media.

2. We do not die for architecture (which we emphasize

at every interview with job candidates). We do not have

to prove anything with our work, let alone be avant-gar-

de. An architect must have time for himself, time needed

to experience ordinary everyday reality, from which he

draws reection and inspiration for design.

3.

It is not our goal to design visual gadgets or spectacu-

lar spaces that look good in visualizations and photos. What

we aim at is to create a valuable environment for life – to

live, to work, to study, to spend time in the city… An envi-

ronment with which a person will identify. Equally import-

ant to us as the buildings themselves is the space between

them and what can happen between people in it [25]. It is

not a coincidence that the title of the book devoted to our

studio does not include buildings, only “life and space”.

4. When we design in the existing context, to us as im-

portant as genius loci is the user’s sense of identity with

the place.

Translated by

Bogusław Setkowicz