UrbandevelopmentinGhent / RozwójGandawy 39

tex tile sector hardest, with a lot of manual work being

moved to low-wage countries. Even the UCO (Union Co-

tonnière), once a ourishing textiles group, fell on hard

times. The decline in transit trac, in the wake of the oil

crisis, also dealt severe blows to the port in Ghent. All at

once, Ghent found itself with a surplus of industrial equip-

ment. A museum was founded in 1978 at the city archive

to collect relics of Ghent’s industrial past.

It was some time before the Museum of Industrial Ar-

chaeology and Textile (MIAT), the forerunner to today’s

Museum of Industry, found a home of its own. What does

a collection of this kind entail? And where should it be

housed? Before an answer was found to these questions,

temporary exhibitions were held in various cultural and

historic buildings in the city. A home was nally found for

the museum in 1991, in the former Desmet-Guequier cot-

ton spinning mill on the Minnemeers in Ghent, where it is

still located today. The building is on the border between

the mediaeval city centre and the 19

th

century suburbs, in

the area that forms the transition between the city and the

port area.

Given the importance of the textile industry for Ghent

and the surrounding region, the museum concentrated on

that branch of industry when it built up its collection be-

tween 1978 and 1989

3

. In the 1990s, however, its focus

widened to encompass the material culture of industrial

society in broader terms. The expansion of the collection

was focused more on the acquisition of objects than on

the development of themes. Most of these objects were

acquired passively as donations, rather than by actively

purchasing missing links. Forty years of collecting has

resulted in a rich and diverse group of sub-collections,

covering the history of textile production as well as areas

such as printing, energy services, the metal industry and

machine construction [2].

Who takes care of the big stuff?

There are two separate Flemish ministries with the au-

thority to protect heritage. The Ministry of Environment

and Planning has the authority to protect monuments and

buildings (immovable heritage). The Ministry of Culture

has the authority to protect movable and intangible herit-

age. When it comes to preserving industrial heritage, this

articial division often provokes challenging disputes.

Is a stationary steam engine movable or immovable? Is

a gantry crane on tracks in the docks movable or immova-

ble? Are massive fermentation tanks at a brewery immov-

able by application? In short, who takes care of “the big

stu”?

In Belgium and Flanders, besides private collectors and

enthusiasts, it is mainly small, local organisations that take

care of the preservation and maintenance of large-scale in-

dustrial and technical heritage. The permanent sta who

look after the collections are often supported by dedicated

3

The museum houses the oldest spinning mule still in working or-

der. This semi-automated cotton spinning machine has been on the list of

Flemish Community Masterpieces since 2010.

volunteers, many of whom are retired [3]. The latter bring

their lifetime of accumulated knowledge from an active

career related to the subject of their current passion. They

are connected to a specic museum, location, installation

or type of heritage that they know through and through.

The commercial pool of restorers interested in large tech-

nology heritage is small. Commercial restoration of large,

working industrial heritage, such as stationary steam en-

gines, is almost non-existent. The lack of a commercial

option forms an obstacle to the further preservation, or

sustainable preservation of knowledge about the preser-

vation – and ideally the restoration – of large technology

heritage. This lack also complicates the redevelopment of

de-industrialized sites that have been abandoned for some

time. Private owners and project developers hesitate to

get involved, although they do react positively to the idea

of keeping the machines or installations on site. They en-

counter diculties in nding the right expertise, whether

in terms of project and nancial planning or appropriately

skilled manpower.

Adaptive reuse, or the appreciation of large technology

heritage in public space, changes over time. It tends to

be sensitive to trends, and if it is not thought through, it

may be poorly received by the public. This specically

applies to large machines that were not initially designed

for outdoor use. Erected at important road intersections,

they are intended as monuments or landmarks, promoting

an active industry by creating a link with a nearby city

or a long and glorious industrial history. Unfortunately

this “roundabout heritage” quickly deteriorates, due to an

under-estimation of the costs of periodic and long-term

maintenance, or because of vandalism.

Large technology heritage can also prove challeng-

ing for museums. The mere size of some of these pieces

means that they may literally weigh on the storage fa-

cilities. Stripped of their context or taken out of their

original environment, they tend to be dicult to integrate

into museum exhibitions or projects. This was the case

for a crane donated to the young MIAT during the period

when industry started moving away from the 19

th

century

port. At that time, in contrast to cities like London and

Antwerp, Ghent lacked a vision for port or maritime her-

itage. Moreover, the outside world experienced the sea

port of Ghent as a remote closed-o area with no real

link to the popular, mediaeval city centre. People only

went there if they needed to. Concerned about the possi-

ble loss of important heritage, the museum accepted the

gift of a crane from La Floridienne, a company trading

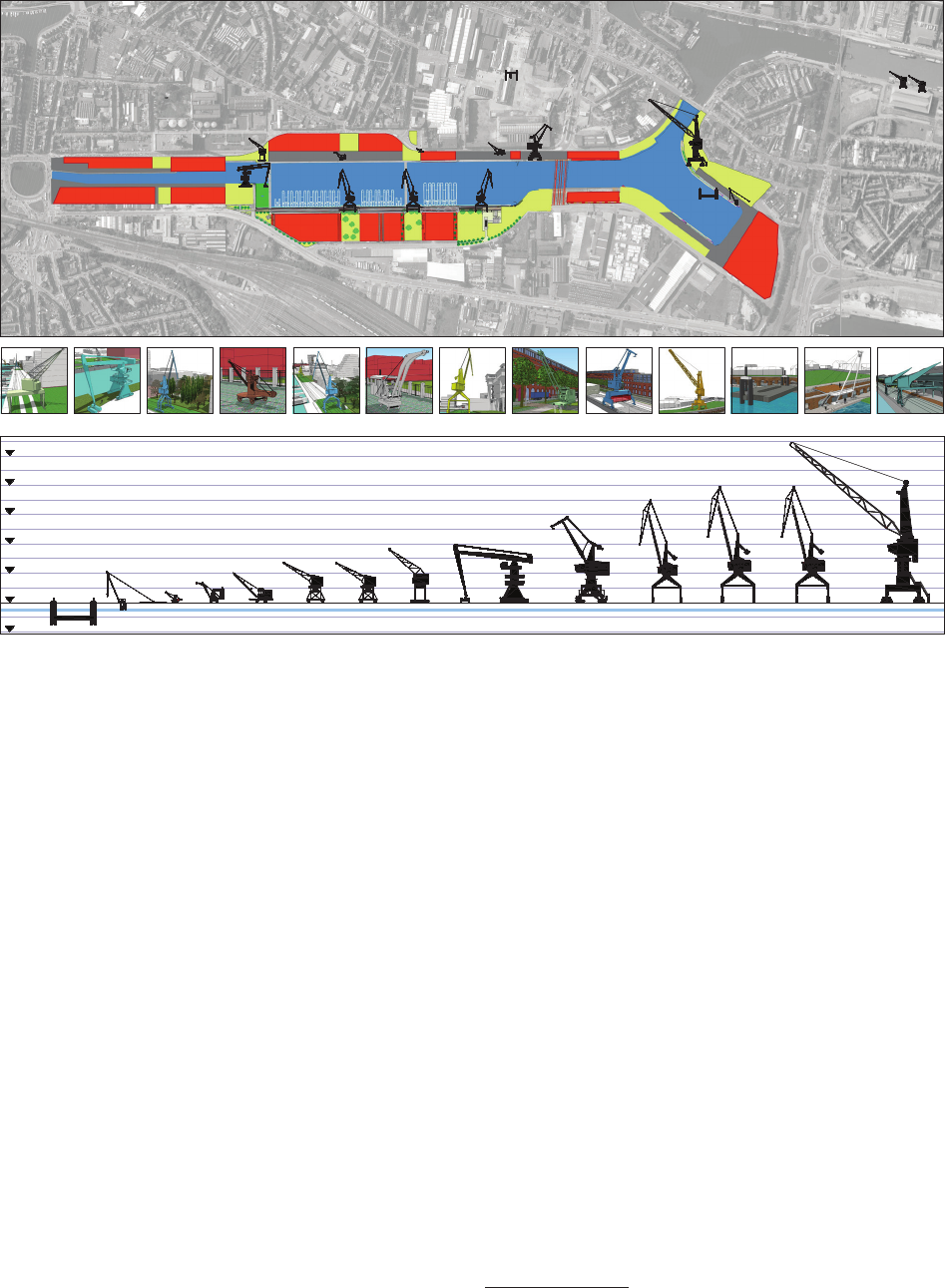

in fertilizers and chemicals. The “Titan” crane rests on

a high portal or gantry section, wide enough to allow two

railway trains to pass underneath, side by side. Origi-

nally commissioned by the city port authorities in 1925,

and constructed by the Antwerp company Titan Anver-

sois, the crane had had an active career on several quays.

However, an inspection revealed that the gantry section

had been damaged by years of exposure to corrosive fer-

tilizers. It was beyond restoration or repair, and scrapped

for safety reasons. A lack of funding and changes in pol-

icy meant that the original plans to erect the crane in the

museum garden, as an eye-catcher and a reference to