124 Krzysztof Klus

References

[1] Gyurkovich M., Mieszkać przy miejskiej przestrzeni publicznej,

“Czasopismo Techniczne” 2010, R. 107, z. 5, 2-A, 145–153.

[2] Klus K., Wpływ lokalizacji mieszkaniowych na prawidłowy rozwój

Krakowa, “Przestrzeń/Urbanistyka/Architektura” 2019, Vol. 2,

7–20, doi: 10.4467/00000000PUA.19.019.11439.

[3] Howard E., Miasta-ogrody jutra, Fundacja Centrum Architektury,

Instytut Kultury Miejskiej, Warszawa–Gdańsk 2015.

[4] Perry C., The Neighbourhood Unit, [in:] R.T. LeGates, T. Stout

(eds.), The City Reader, Routledge, London 2011, 486–498.

[5] Le Corbusier, Karta ateńska, Fundacja Centrum Architektury, War-

szawa 2017.

[6] Jeleński T., Urbanistyka i gospodarka przestrzenna, [in:] J. Kro-

nenberg, T. Bergier (red.), Wyzwania zrównoważonego rozwoju

w Polsce, Fundacja Sendzimira, Kraków 2010.

[7] Dąbrowska-Milewska G., Czy w Polsce potrzebne są krajowe stan-

dardy urbanistyczne dla terenów mieszkaniowych?, “Architecturae

et Artibus” 2010, Vol. 2, No. 1, 12–16.

[8] Dąbrowska-Milewska G., Standardy urbanistyczne dla terenów

mieszkaniowych – wybrane zagadnienia, “Architecturae et Arti-

bus” 2010, Vol. 2, No. 1, 17–31.

[9] Hennig K., #Law4Growth policy paper #5: Planowanie przestrzen-

ne, Forum Prawo dla Rozwoju #Law4Growth, Warszawa 2020.

[10] Grudziński A., Standard urbanistyczny zabudowy mieszkaniowej,

“Człowiek i Środowisko” 1998, t. 22, nr 1–2, 95–110.

[11] Klus K., Mistrzejowice-Batowice Modelowy zespół miejski wg TOD

w Krakowie, master thesis, Politechnika Krakowska, Kraków 2019.

[12] Gaczoł A., Kraków. Ochrona zabytkowego miasta. Rzeczywistość

czy kcja, WAM, Kraków 2009.

[13] Sumorok A., The idea of the socialist city. The case of Nowa Huta

“Technical Transactions” 2015, R. 112, z. 12-A, 303–340, doi:

10.4467/2353737XCT.15.384.5003.

[14] Wrzos M., Ruczaj – krakowska dzielnica przyszłości?, https://wia-

domosci.onet.pl/krakow/ruczaj-krakowska-dzielnica-przyszlosci/

wdvf0vx [accessed: 3.02.2021].

[15] Skarbek T., Powstanie kampusu. Krok po kroku, https://www.uj.

edu.pl/kampus/historia-budowy [accessed: 3.02.2021].

[16] Gurgul A., Ruczaj – sypialnia Krakowa z niewygodami. Skąd ten

chaos?, https://krakow.wyborcza.pl/krakow/1,44425,17862947,

Ruczaj___sypialnia_Krakowa_z_niewygodami__Skad_ten.html

[accessed: 3.02.2021].

[17] Komorowski W., Ochrona dziedzictwa urbanistyki i architektu-

ry Nowej Huty z lat 1949–1959, “Wiadomości Konserwatorskie”

2017, nr 49, 153–162, doi: 10.17425/WK49CONSERVATION.

[18] Gmina Miejska Kraków, Portal MSIP Obserwatorium, https://

msip.krakow.pl/ [accessed: 3.02.2021].

[19] Uchwała nr CXII/1700/14 Rady Miasta Krakowa z dnia 9 lipca

2014 r. w sprawie uchwalenia zmiany „Studium uwarunkowań

i kie runków zagospodarowania przestrzennego Miasta Krakowa”,

https://www.bip.krakow.pl/?dok_id=167&sub=uchwala&query=

id%3D20321%26typ%3Du [accessed: 24.02.2021]

[20] Statystyczne Vademecum Samorządowca 2020, miasto Kraków,

Urząd Statystyczny w Krakowie, http://krakow.stat.gov.pl/vademe-

cum/vademecum_malopolskie/portrety_miast/miasto_krakow.pdf

[accessed: 24.02.2021].

[21] Motak M., Historia rozwoju urbanistycznego Krakowa w zarysie:

podręcznik dla studentów szkół wyższych, Wydawnictwo Politech-

niki Krakowskiej, Kraków 2019.

[22] Płazik M., Przemiany funkcji handlowo-usługowych w mieście

postsocjalistycznym na przykładzie Nowej Huty, [in:] E. Kacz-

marska, P. Raźniak (red.), Społeczno-ekonomiczne i przestrzenne

przemiany struktur regionalnych, t. 1, Ocyna Wydawnicza AFM,

Kraków 2014, 85–100.

[23] Wyszukiwarka połączeń komunikacyjnych, https://jakdojade.pl

[accessed: 21.02.2021].

[24] Overstreet K., Creating a Pedestrian-Friendly Utopia Through the

Design of 15-Minute Cities, “ArchDaily” 2021, 15 January, https://

www.archdaily.com/954928/creating-a-pedestrian-friendly-utopia-

through-the-design-of-15-minute-cities [accessed: 30.01.2021].

urban design standards, understood as codied in the form

of either bill, regulation, codex or norm containing a set of

rules dening minimal standards of accessibility to various

facilities and services, primarily those of a public domain,

is considered to be crucial. The author believes that leg-

islation should apply, above all, to the local government

during the development of local zoning plans. The design

process ought to contain estimations of a target popula-

tion, which would be a basis for elaborating demand for

a given type of service. Having said that, it is important to

limit the number of investments that proceed with WZiZT

decisions, by covering the whole country with local zon-

ing plans. Arguably, a way of achieving that state would

be to put legislative, social and media pressure on local

government units. A guarantee of meeting these require-

ments should be obligatory to get an investment approval.

It must not be forgotten that provision of public services

lies in the hands of the local government. For that reason,

an expense of building such objects should not be paid

by a private real estate developer, even if he decides to

build a residential estate for several thousand residents.

Clearly building a healthcare facility or a school is an

expensive investment for a local government, however it

would reimburse the costs in taxes. Taking into consid-

eration a state-wide housing shortage and limited budget

of the local government, an optimal solution seems to be

a public-private partnership. Due to a high risk of fraud,

such solutions must be precisely monitored.

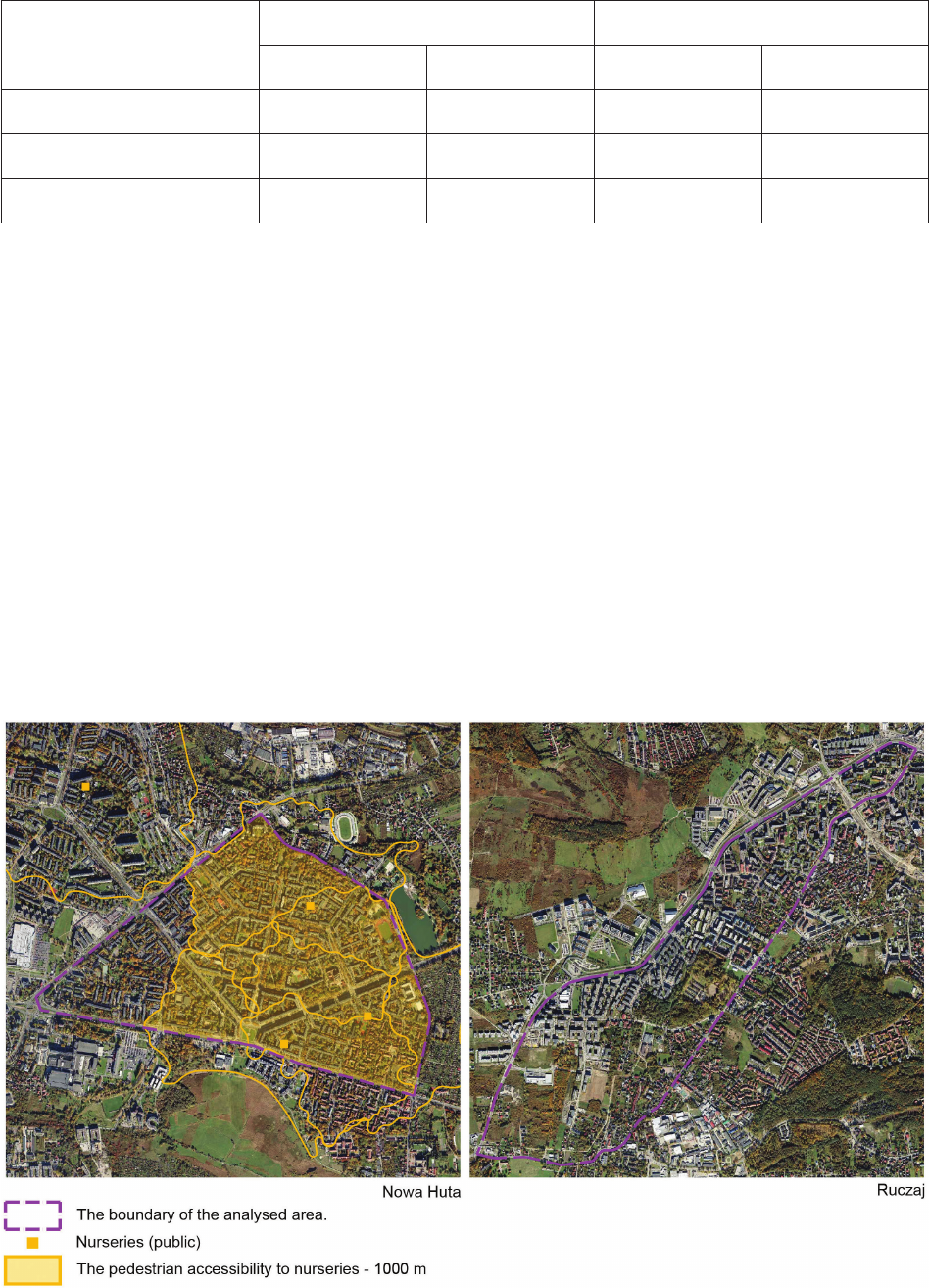

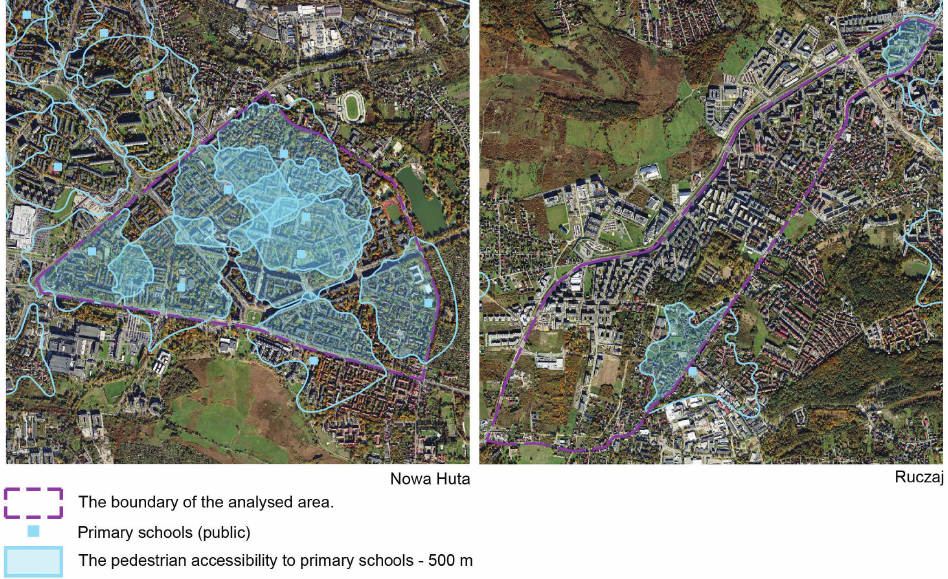

Plans that are in accordance with the idea of the neigh-

bourhood unit and the 15-minute city [24] ought to provide

all basic services within walking distance. Additionally

pedestrian infrastructure should be welcoming, safe and

attractive, so it would convince people to resign from us-

ing their cars. In that aspect, housing development density

is important. This should be achieved with the approval of

citizens, because it fosters better accessibility to various

facilities. Such a process does not have to be accompanied

by a negative, subjective feeling of “concreting” a city.

The presented cases are proof of that. In accordance with

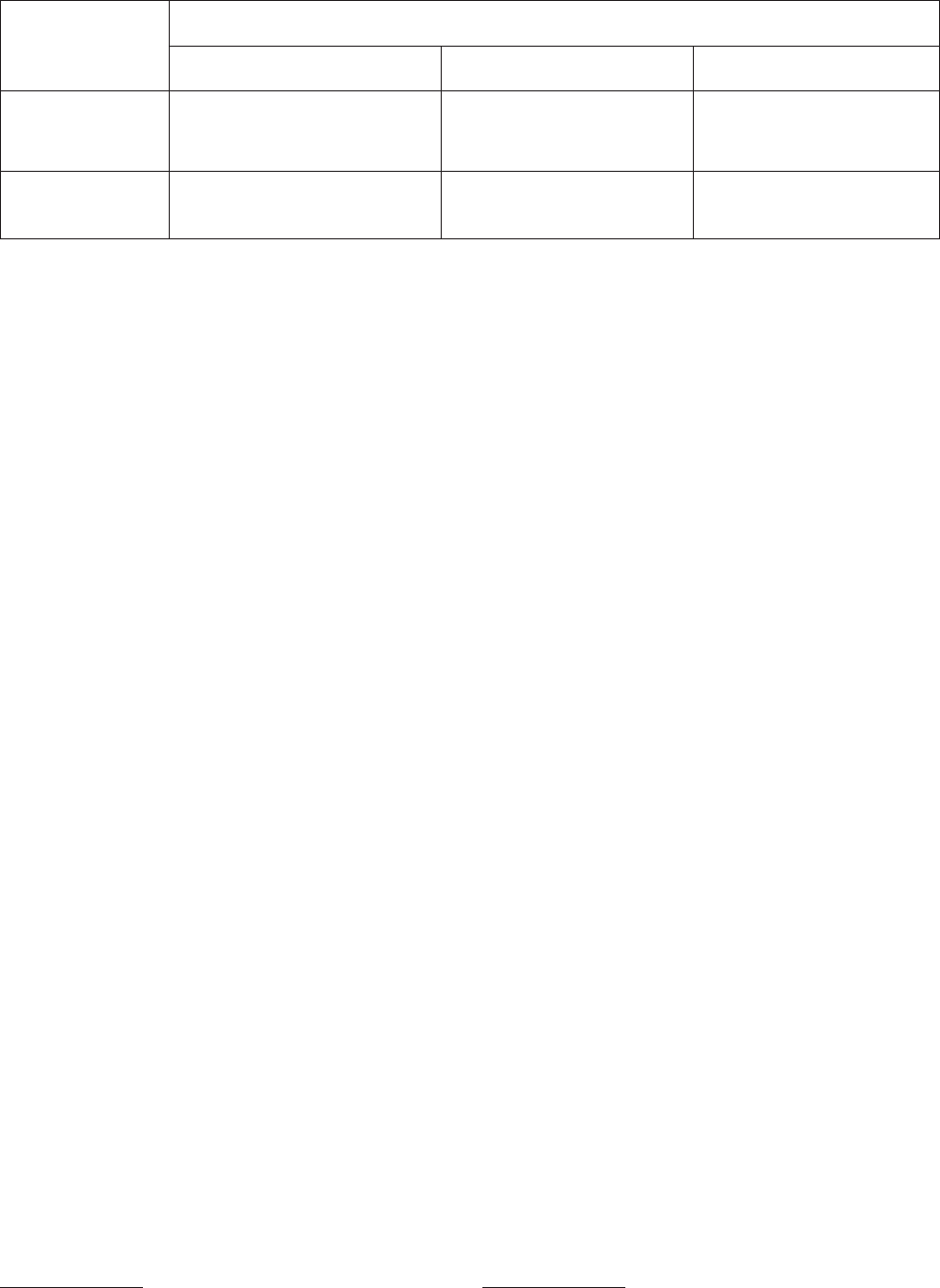

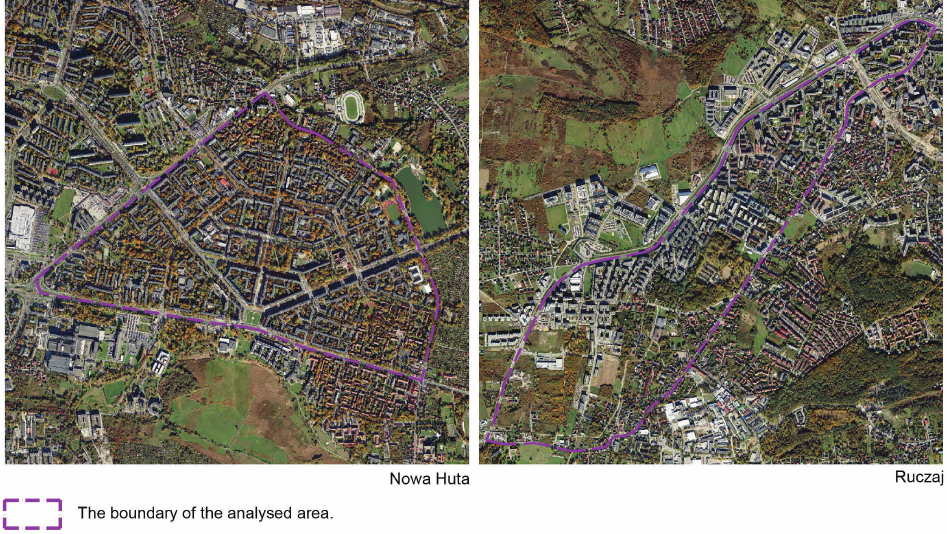

the data presented in Research part of this paper, Nowa

Huta, considered one of the greenest districts in Cracow,

has signicantly higher population density than Ruczaj,

which is perceived as a symbol of “concreting” the city.

Translated by

Michał Ogorzałek, Joanna Maliborska