78 Ewa Cisek

The concept of their selection must also be applied in the

future, which means that owners of ats cannot interfere

in the designed plant compositions, change them, or elim-

inate them. Thanks to this approach, ecosystems are sta-

ble, native, and remain in a constant balance. At the end

of this complex process, the functional and spatial sys-

tem of a building with a division into publicly available,

semi-private, and private spaces within the structure of

ats and created gardens is designed.

Similarly to the other Dutch implementations of the au-

thor of the project, apart from the oce space and apart-

ments, 30% of this layout are social ats with signicantly

reduced rents. This detail proves that pro-environmental

and social activities are combined, which brings satisfac-

tory results.

Façades, which are lled with trees and shrubs, are not

only cyclically recurring colour phenomena as an imita-

tion of the year-round vegetation cycle of plants. They

also form a design strategy to increase the share of the bio -

logically active tissue in the structure of the city. These

actions substantially improve the quality of urban air and

signicantly reduce the urban heat island eect. The trees

in the structure of towers produce an average of 41 tons

of oxygen per year, sucking carbon dioxide and capturing

ne particles of dust. They produce the amount of oxygen

equivalent to the one obtained from one hectare of forest.

The green tissue clearly cools the façade in summer and

provides full insolation in winter when plant branches

shed their leaves. Thanks to this solution, the costs con-

nected with air conditioning of buildings are reduced [21].

At the same time, the sun rays which lter through the

crowns of trees, give the eect of Nordic light in residen-

tial interiors – a phenomenon occurring on forest glades

surrounded by high trees or in Norwegian small churches

stavkirke. This quality of space was used for the rst time

in architecture by Norwegian architect Sverre Fehn when

designing Nordic Pavilion (Norwegian Nordens paviljong,

implementation in 1962) at Venice Biennale, where a key

role in the structure of the building was played by trees

– newly designed and those outside within the park [22].

This implementation from Belgium is an example of

con structing a stable ecosystem which consists of fauna

and ora species characteristic of a given location. The

building is a supporting structure for it, with a given form

which improves the plant exposure to sunlight and supplies

the plants with rainwater. This concept promotes the recon-

struction and protection of local wild ecosystems as a meth-

od of increasing the species biodiversity and eco-education.

Palazzo Verde is a vertically designed local ecosystem,

which is a kind of green acupuncture of Antwerp. Appear-

ing in the city, it plays the role of “vanguard” of changes

and sets a new direction by introducing native nature into

the structure of the built environment. This solution is an

alternative to the existing urban planning which isolates

natural systems and dehumanizes the human living envi-

ronment. The colours which nally the image of the build-

ing obtains, i.e. unique just like in nature, are cyclically

changed, which makes them harmoniously become a part

of a larger image of the organic city, and thus becoming its

unrepeatable and attractive showcase.

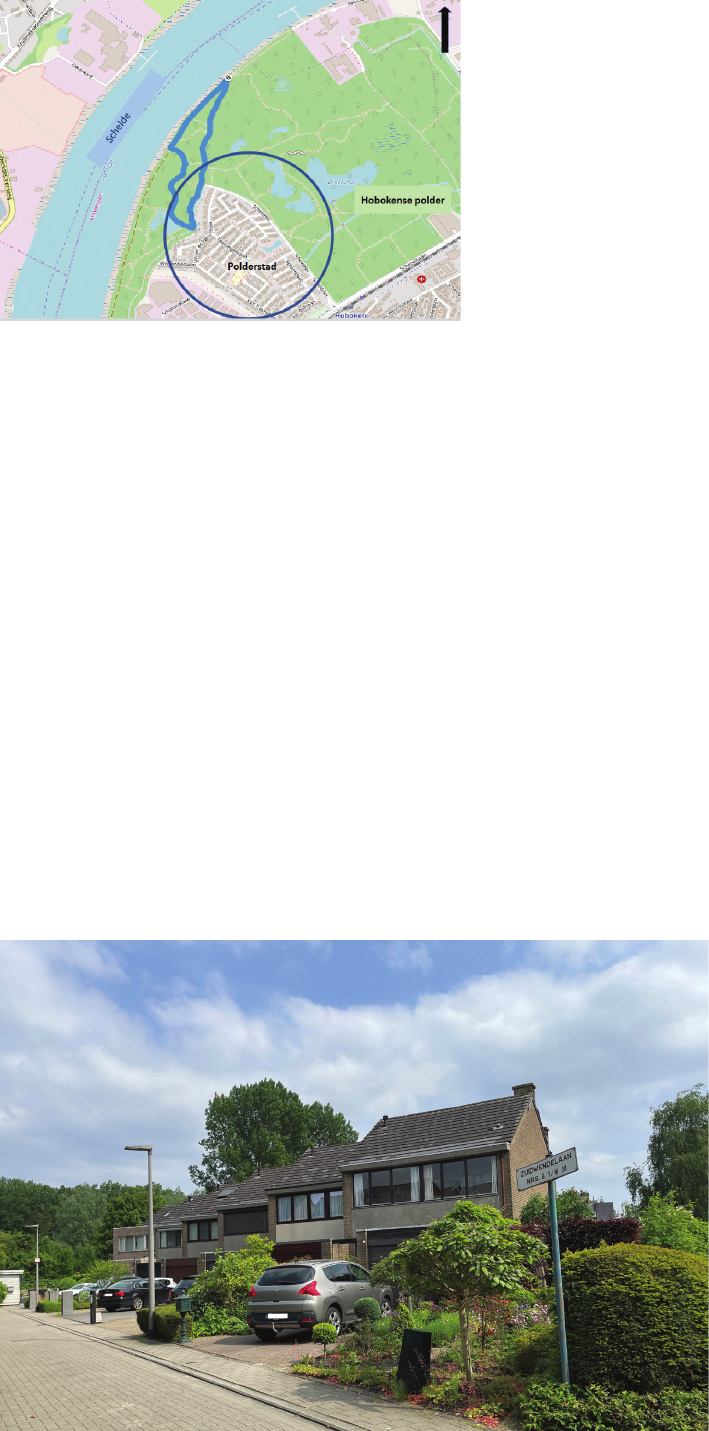

Hobokense Ecological Education Park

– an example of transforming urban brown fields

into a new urban ecosystem

Eco-friendly architecture which is integrated with Eco-

logical Education Parks constitutes another form of spatial

organization of housing architecture that is conducive to

climate neutrality in cities. These new urban ecosystems

form closed wild local ecosystems which are created on

the basis of the existing forest and park greenery centred

around watercourses and water reservoirs. They are char-

acterized by semi-natural vegetation, limited maintenance

treatments, emphasis on education, and the use of ecolog-

ical succession as the creator of the park or a part of it [1].

The environmental context seems to be crucial for orga-

nizing this type of eco-structures because development on

the basis of place is the basis of all actions. This long-term

approach supports such values as increasing biodiversity

and eco-education of inhabitants of the city. Its fundamen-

tal assumptions include friluftsliv (Norwegian) – the joy

of identication with wild nature, i.e. going out to nature,

which ensures necessary balance and empathy [22]. In

the urban context, this role is performed by new urban

ecosystems, i.e. Ecological Education Parks and related

functions such as housing, including houses for seniors

and educational – forest kindergartens and schools, ser-

vice – small gastronomy based on local products and com-

munity spaces.

The main purpose of designing these urban eco-struc-

tures is the reconstruction of local ecosystems, which leads

to an increase in biological diversity in a given area, mod-

elling of ecological succession processes, as well as the

mosaic character of plant communities. Jakubowski aptly

notes that adaptations of urban brownelds for ecologi-

cal education parks make it possible to create new mo-

dels of leisure and recreational parks, where wildness is

a form consciously protected or introduced [1, p. 2]. This

function results in another goal, which is eco-education.

Thanks to it, inhabitants acquire knowledge about natural

processes and cycles which take place in ecosystems and

integrate in connection with protective actions. The last

and most important purpose, which is closely related to

the previous ones, is the reduction of the heat island eect

in the city and the improvement of air quality.

Such activities are perfectly reected in the Hobokense

Ecological Education Park in Antwerp and two connected

housing complexes, i.e. Polderstadt and Groen Zuid (ar-

chitect Binst Architects, implementation in 2020). This

implementation is an example of restoring and recon-

struction of the local wild ecosystem in the former polder

of the Shelde River and its strict integration with housing

architecture. Numerous small water reservoirs, eco-edu-

cational thematic paths, wooden shelters – walls for ob-

serving water avifauna and bridges above the wetland

habitats were designed within the park (Figs. 3, 4). There

has also been a return to the idea of farm animals grazing

in cities, which helps protect meadow environments and

makes it possible to maintain biodiversity appropriate for

the early stages of succession and exposure of valuable

views. Quoting Jakubowski […] the presence of animals