Zegary słoneczne kościoła pw. Wniebowzięcia Najświętszej Panny Marii w Gdańsku /Sundials of St Mary’s Church in Gdańsk 9

uszkodzeń, z wyjątkiem wymienionej w tym miejscu ce

gły, lub też podobnie jak w przypadku zegara zachodniego

wskazówka zamocowana była tylko w jednym punkcie.

Lokalizacja wschodniego zegara słonecznego była nie

przypadkowa. Umieszczony został na ścianie południo

wej kościoła, gwarantującej najlepsze doświetlenie, a więc

także odczytywanie danych godzin. Dodatkowo było to

bardzo korzystne miejsce ze względów kompozycyjno

użytkowych. Znajdowało się w pobliżu wejścia do wnę

trza transeptu, w połowie odległości między oknami

(środkowym i zachodnim) oraz w połowie ich wysokości.

Zegar był stąd dla wszystkich widoczny, szczególnie dla

osób idących od strony Ratusza Głównego Miasta (siedzi

by rady miejskiej) przy ul. Długiej w stronę wejścia do

świątyni.

Wyniki badań

Z zachowanych materiałów archiwalnych przedstawiają

cych elewację południową kościoła Mariackiego z XIX w.

dowiedzieć się można głównie o pierwszym zegarze (za

chodnim), gdyż dość czytelna jest jego tarcza. Na najstar

szych rycinach elewacji południowej wykonanych przez

Petera Willera (ok. 1687) i Barthela Ranischa (1695) wi

doczny jest tylko jeden zegar (zachodni). Na obydwu od

bitkach graficznych zegar ten znajduje się po lewej stronie

(zachodniej) okna zachodniego, jednakże tylko pierwszy

z autorów umieścił go na wysokości zbliżonej do reali

stycznej. Miejsce drugiego zegara (wschodniego) zaryso

wane jest cegłami przeciętymi rynną ciągnącą się od kosza

między dachami transeptu (środkowym a zachodnim) aż

do kamiennego cokołu ściany. W dokumentacji rysunko

wej opublikowanej w 1929 r. przez Karla Grubera i Ericha

Keysera miejsce tego zegara, bez wyjaśnienia, jest ozna

czone białym prostokątem (il. 7). Naj lepsza dokumenta

cja fotograficzna pochodząca z około 1870 r. ukazuje

fragmenty tynków tarczy zegarowej przecięte rynną.

Ponieważ na fotografiach wykonanych po 1930 r. nadal

widoczne są jedynie relikty tynku, można wysnuć wnio

sek, że jego obrys przedstawiony na wspomnianej inwen

taryzacji jest rekonstrukcją jego pierwotnej wielkości.

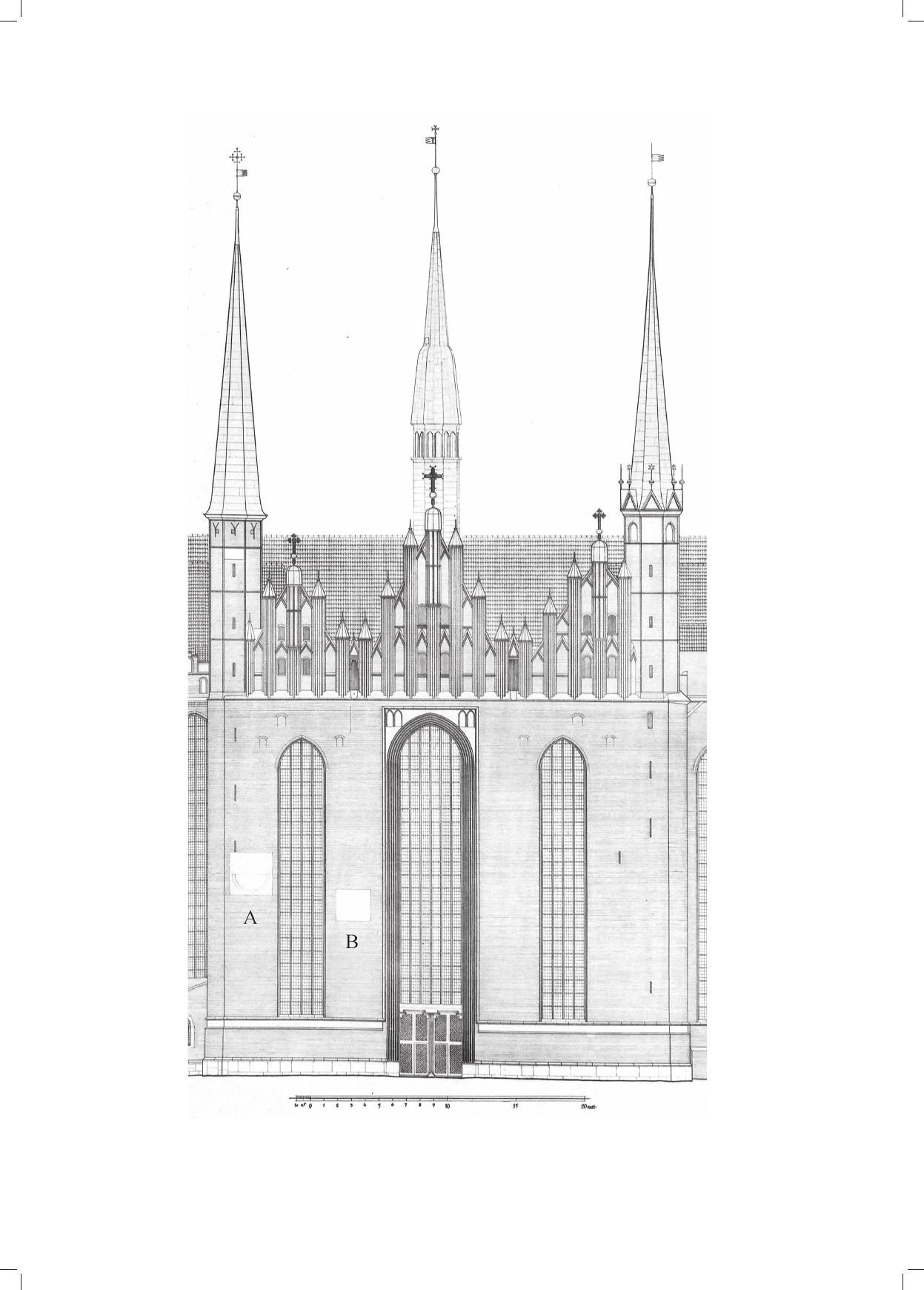

Fragmenty tynku uznane za część tarczy zegara wschod

niego zachowały się na mniej więcej 53% powierzchni.

Największe ubytki znajdują się w środkowej części oraz

przy krawędziach tarczy. Pomimo zachowania jedynie

niewielkich śladów, można ustalić część danych pewnych

i danych o znacznej pewności. Do tych pierwszych należy

plan tarczy zegarowej, miejsce osadzenia polosa i kąt jego

położenia. Z faktu braku jego zaznaczenia już na rycinie

z 1687 r. wynika, że zegar ten musiał być wcześniej zlikwi

dowany. Ona też ujawnia przyczynę tego działania. Zda

wałoby się, że wybrane miejsce dla zegara słonecznego

było wszechstronnie przemyślane. Okazało się jednak ina

czej. Miało zasadniczą wadę. Znalazło się dokładnie pod

koszem dzielącym połacie dwóch zachodnich dachów

transeptu. Woda opadowa z tych połaci dachowych była

odprowadzana do kosza, następnie za pomocą wysuniętych

rzygaczy ciskana, zwłaszcza przez wiatr, na ścianę tran sep

tową i spływała aż do gruntu. Powodowało to częste zacie

kanie i powolne niszczenie tynkowej tarczy zegarowej.

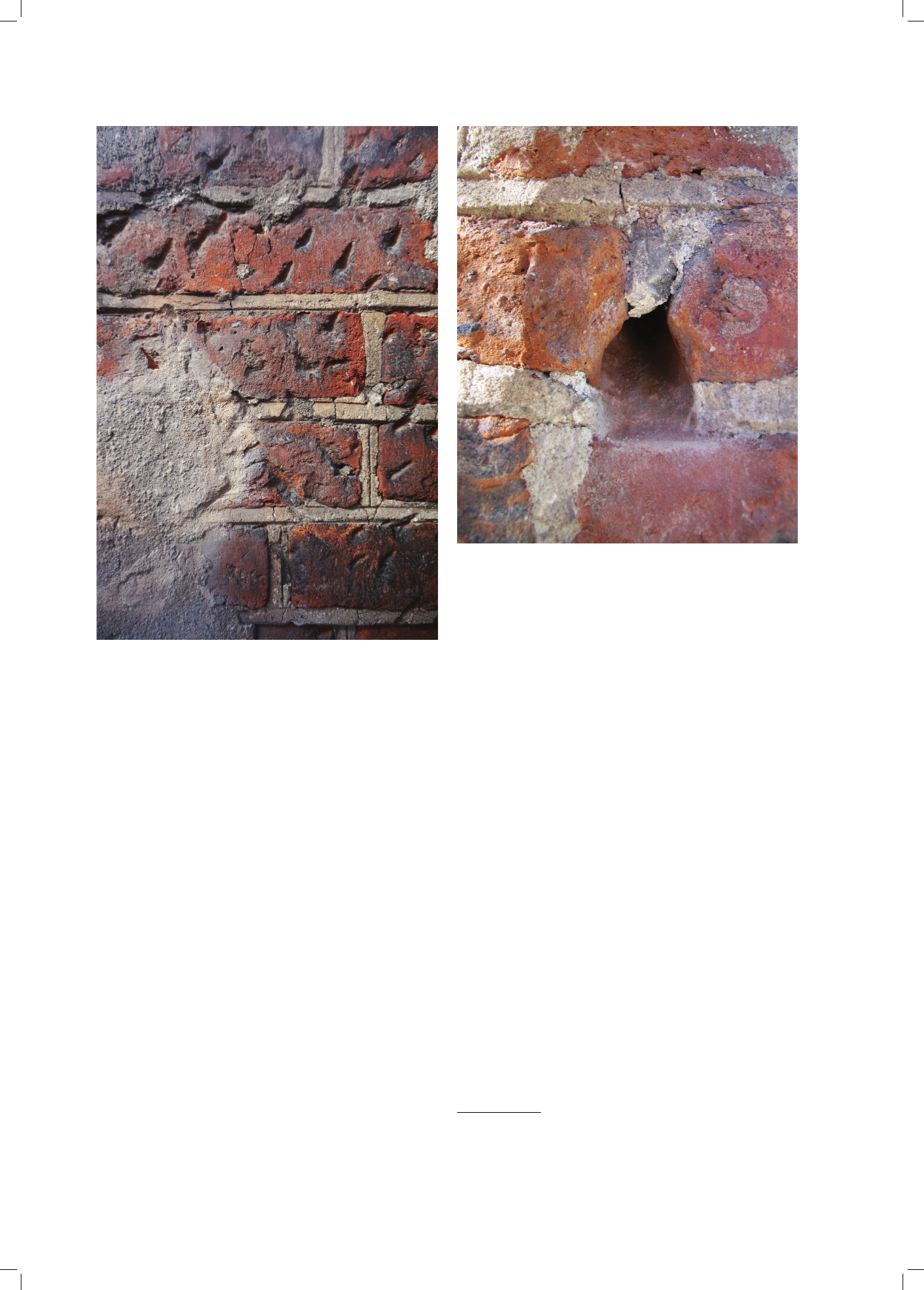

oblique course towards the wall surface rising up into the

wall was uncovered. The angle of its inclination is 35–

40º. This trace is interpreted as the place of fixing the

polos, whereas the angle of the course of the opening – its

inclination towards the plane of the face (Fig. 5, 6).

According to the principle of the sundial’s structure, its

hand must be parallel to the Earth’s axes of rotation, i.e. it

must lie in the area of the local meridian [9, p. 6]. This

feature in shown the following formula: 90º – ȹ (the

range of latitude). For St Mary’s Church in Gdańsk, the

range ȹ is 54º20'59''N, which roughly gives an angle of

inclination of the polos equal to 35º40', and thus con

tained in the data obtained empirically. In order for the

sundial hand to provide permanent and exact timing, it

should have some additional support. However, no un

equivocal traces of it could be found. This allows us to

conclude that its placement could have been located about

30 cm lower because there are no adequate damages any

where, except for the brick replaced there or similarly to

the case of the western clock where the hand was fixed

only at one point.

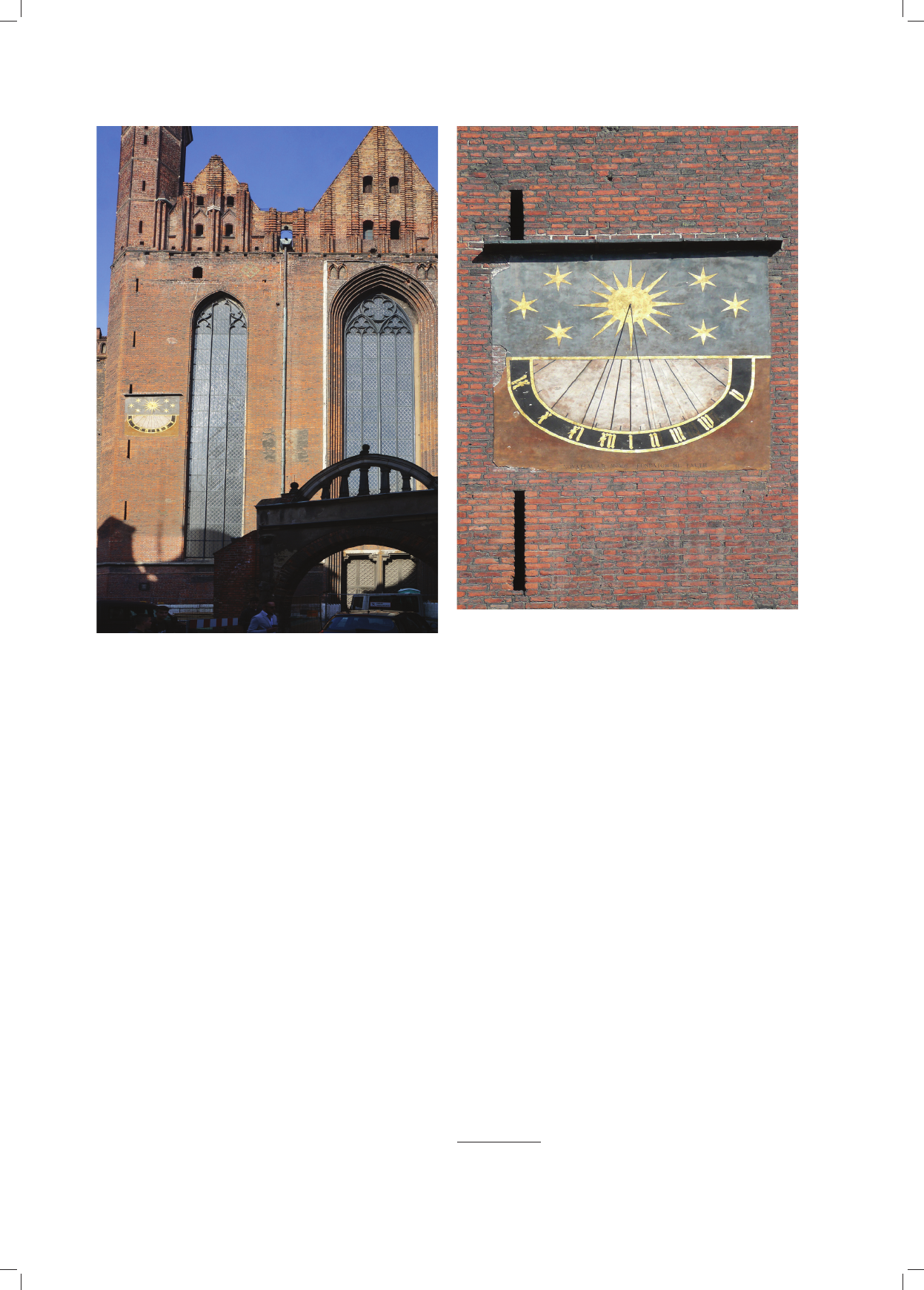

The location of the eastern sundial was not accidental.

It was placed on the southern wall of the church, which

guaranteed the best illumination and thus also reading a giv

en time. Moreover, it was a very favourable place for

compositional and utility reasons. It was near the entrance

to the interior of the transept and halfway between the

windows (middle and western) and half of their height.

The clock was visible to everyone from that place, in par

ticular for people walking from the Main City Town Hall

side (the seat of the city council) in Długa Street towards

the entrance to the temple.

Research results

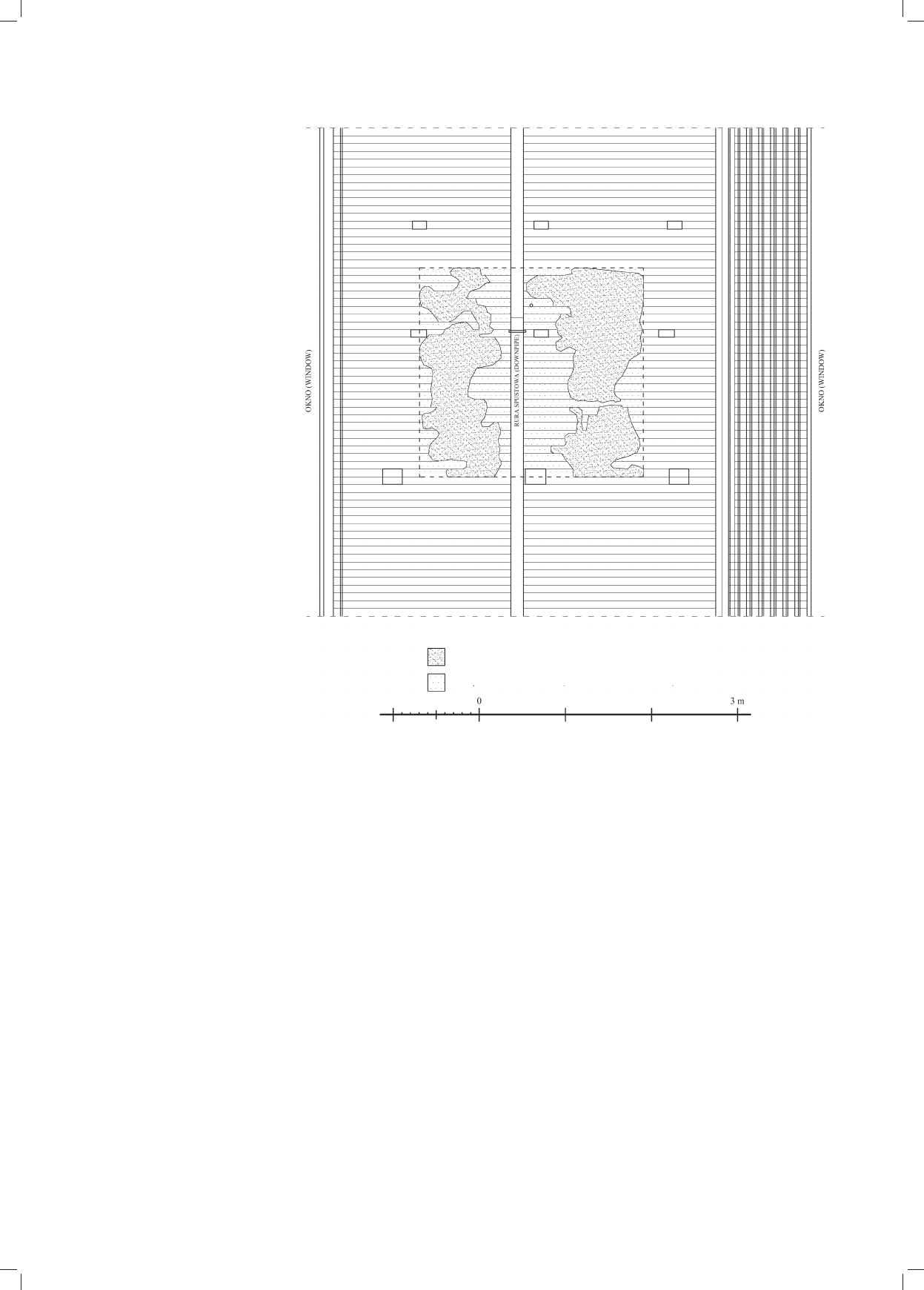

On the basis of the preserved archival materials depict

ing the southern facade of St Mary’s Church from the 19

th

century, we can learn mainly about the first (western)

clock because its face (dial) is quite clear. On the oldest

drawings of the southern facade, which were made by

Peter Willer (c. 1687) and Barthel Ranisch (1695) only

one clock (western) is visible. On both graphic prints, the

clock is located on the left side (western) of the western

window, however only the first of the authors placed it at

a level close to the realistic one. The place of the second

(eastern) clock is outlined with bricks cut by a gutter ex

tending from the basket between the roofs of the transept

(middle and western) up to the stone plinth of the wall. In

the drawing documentation, which was published by Karl

Gruber and Erich Keyser in 1929, the place of this clock

– without any explanation – is marked with a white rect

angle (Fig. 7). The best photographic documentation from

about 1870 shows parts of the plaster of the clock face cut

through by a gutter. Due to the fact that in the photographs

taken after 1930 only relics of plaster are still visible,

it can be concluded that its outline presented on the men

tioned inventory constitutes the reconstruction of its ori

ginal size.

The fragments of the plaster recognized as part of the

eastern clock face are preserved on approximately 53%