112 Aneta Biała

thorities have turned their attention to sustainable develop-

ment, emphasizing environmental protection and creating

additional green areas. In 2005, Montreal adopted its rst

Sustainable Development Strategic Plan, which represents

a collective commitment to making sustainability the foun-

dation for the city’s future development. One of the plan’s

objectives was to protect biodiversity, natural habitats, and

green spaces, including increasing the area of protected nat-

ural habitats to 8% of the total area of the island under the

city’s jurisdiction (City of Montreal 2008). With its unique

topography and diverse landscape, Montreal began to regain

its reputation as a city where urban greenery harmoniously

coexists with development. Parks, gardens, and riverside

promenades create picturesque landscapes, attracting resi-

dents to use green spaces. Currently, the City of Montreal

plays a signicant role in promoting biodiversity initiatives

internationally (City of Montreal 2008).

In the research history of cities, the analysis of urban en-

vironments often remains overshadowed (Dagenais 2008).

Most scientists focused primarily on studying natural eco-

systems rather than the human environment. Cities were

con sidered less signicant in scientic research because

re searchers were primarily focused on eorts to halt envi-

ronmental degradation and condemn the excessive exploita-

tion of natural resources in the name of market economy.

In their eyes, cities were seen as enemies of nature, places

that harmed the surrounding environment. Although today

the relationships between social and natural environments

are the subject of intensive research by environmental his-

torians, studies on cities remain relatively neglected. In re-

cent years, ideas related to how people interact with their

surrounding nature have developed and extended beyond

activist and political aspects. Research on the history of

cities from an environmental perspective now requires an

analysis of the relationships between people and natural el-

ements, taking into account the dynamic changes occurring

on both sides of this equation. As historian Geneviève Mas-

sard-Guilbaud (Dagenais 2008) explains, the environmen-

tal approach to history rejects the concept that humans are

external observers of nature, instead accepting the idea of

their integral inclusion in the biosphere, from social units to

entire ecosystems.

Scaling space through greenery modelling

in selected examples

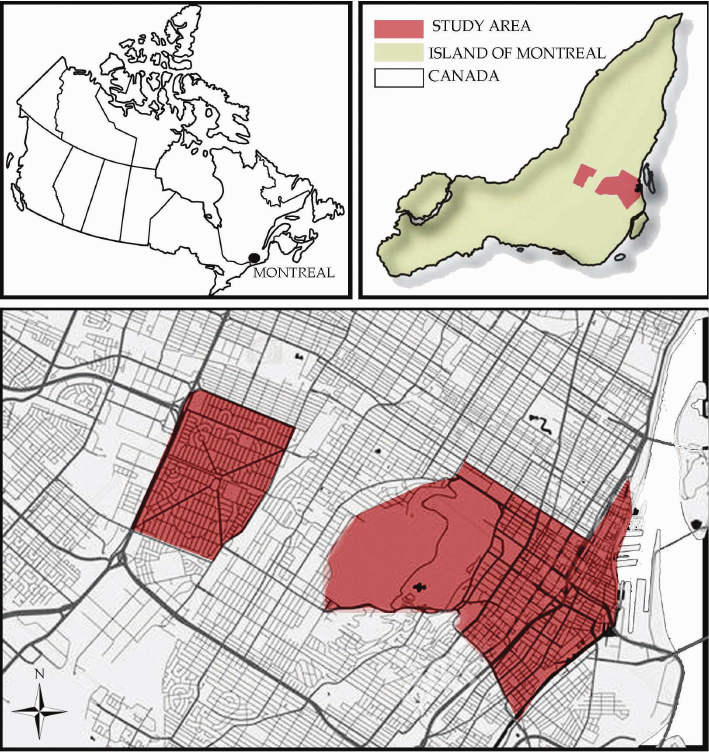

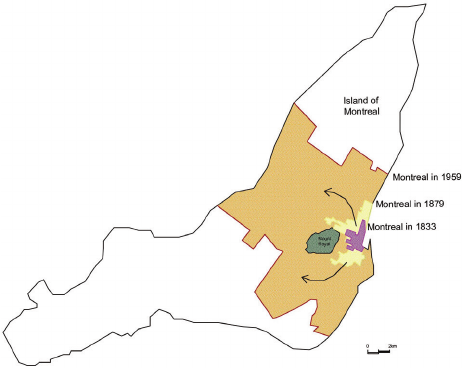

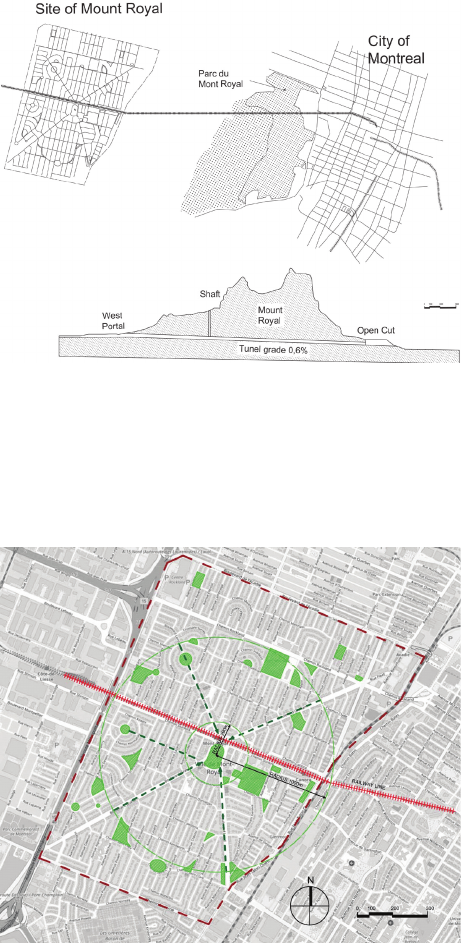

The urban layout of downtown Montreal is character-

ized by a grid of streets running perpendicular or parallel to

Mount Royal Park, creating a regular pattern with geometric

designs. This urban structure is partly inspired by the moun-

tain, located to the west of downtown, which is a dominant

feature of the city’s landscape (Fig. 3). Its presence not only

provides a picturesque backdrop but also inuences the orga-

nization of the urban space. The central area of Montreal fea-

tures a unique urban layout that has evolved over the years.

It is centered around two main axes – Rue Sainte-Catherine

and Rue Sherbrooke (Lord 2016) – serving as the commer-

cial, cultural, and business hub of the city. Rue Sainte-Cath-

erine, one of the main shopping thoroughfares, serves as the

primary east-west axis, oering numerous shops, boutiques,

such as playground equipment, picnic tables, pavilions, etc.,

emphasizing the change in perception of these green spaces

as functional recreational centres rather than merely aesthetic

natural havens (Dagenais 2008).

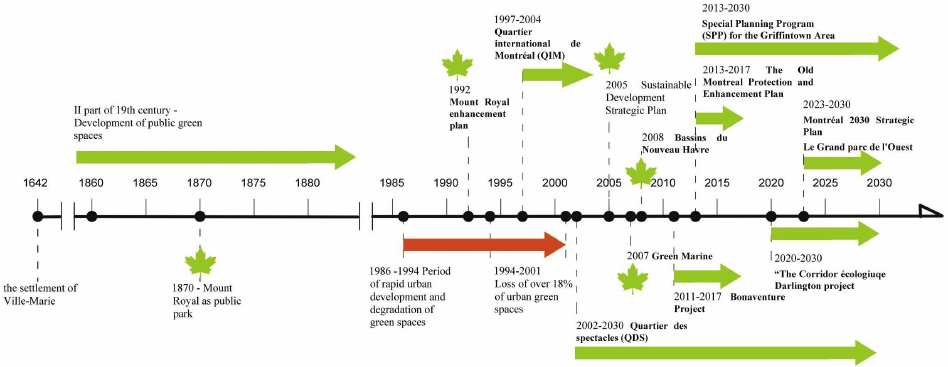

Since the establishment of the settlement, Mount Royal

has played an important role for its inhabitants, who often

went there for picnics or to enjoy the scenery (Debarbieux

1998). In the 1870s, eorts began to shape the area to meet

the social expectations of that time. It was then decided to

create two cemeteries and a public park on the mountain’s

grounds. This was aimed at preserving the natural heritage

but also providing residents with a place for rest and recre-

ation. Frederick Law Olmsted, a renowned landscape archi-

tect and the creator of Central Park in New York, was ap-

pointed to design this area (Debarbieux 1998). His creative

approach to park planning facilitated the harmonious inte-

gration of the mountain terrain into the urban fabric, while

emphasizing its uniqueness. Olmsted, staying true to his

ethical and aesthetic principles, adapted the concept of En-

glish landscape to the specics of the American context. He

introduced articial elements, while striving to make them

almost invisible in the natural environment. This rst en-

counter with diverse topography in his career prompted him

to reject the idea of a traditional park in favour of revealing

the “genius loci” – the characteristic spirit of that particular

place (Debarbieux 1998).

The increase in the city’s population necessitated the in-

cor poration of green areas into central city areas, providing

re sidents with access to parks and recreational areas. In

the post-war period, the phenomenon of suburbanization

emerged, where residents moved to the suburbs in search

of more space and tranquility. As part of this process, urban

greenery became a key element of spatial planning. The cre-

ation of new neighbourhoods involved the consideration of

green spaces, parks, and promenades to maintain a balance

between urban elements and the natural landscape. However,

due to intense and somewhat uncontrolled city development

between 1986 and 1994, half of the forests were built upon,

and between 1994 and 2001, another 750 ha of greenery

were lost (Oljemark 2002), ultimately losing 18% of green-

ery by 2005 (Pham et al. 2011). The city’s policy at the time

did not sit well with the residents, who placed more impor-

tance on maintaining existing green areas and

creating new

recreational spaces in the city. The inuence of residents on

the decision of city authorities regarding green areas can

be exerted through various mechanisms, including partic-

ipation in public consultations, petitions, actions of social

groups and non-governmental organization (NGO), and en-

gagement in electoral processes (Burstein 2003). Residents

often engage in active actions to express their opinions and

demands regarding the protection of green areas and the

development of recreational spaces in their area. This high-

lights the signicant role of society in shaping municipal

policies concerning the natural environment and recreation,

as well as the need for active dialogue between residents

and authorities in the decision-making process regarding

public spaces.

In the face of challenges related to overcrowding and

main taining quality of life, pressure from public opinion re-

pre sented by the Green Coalition on green issues, city au-