88 Ewa Cisek

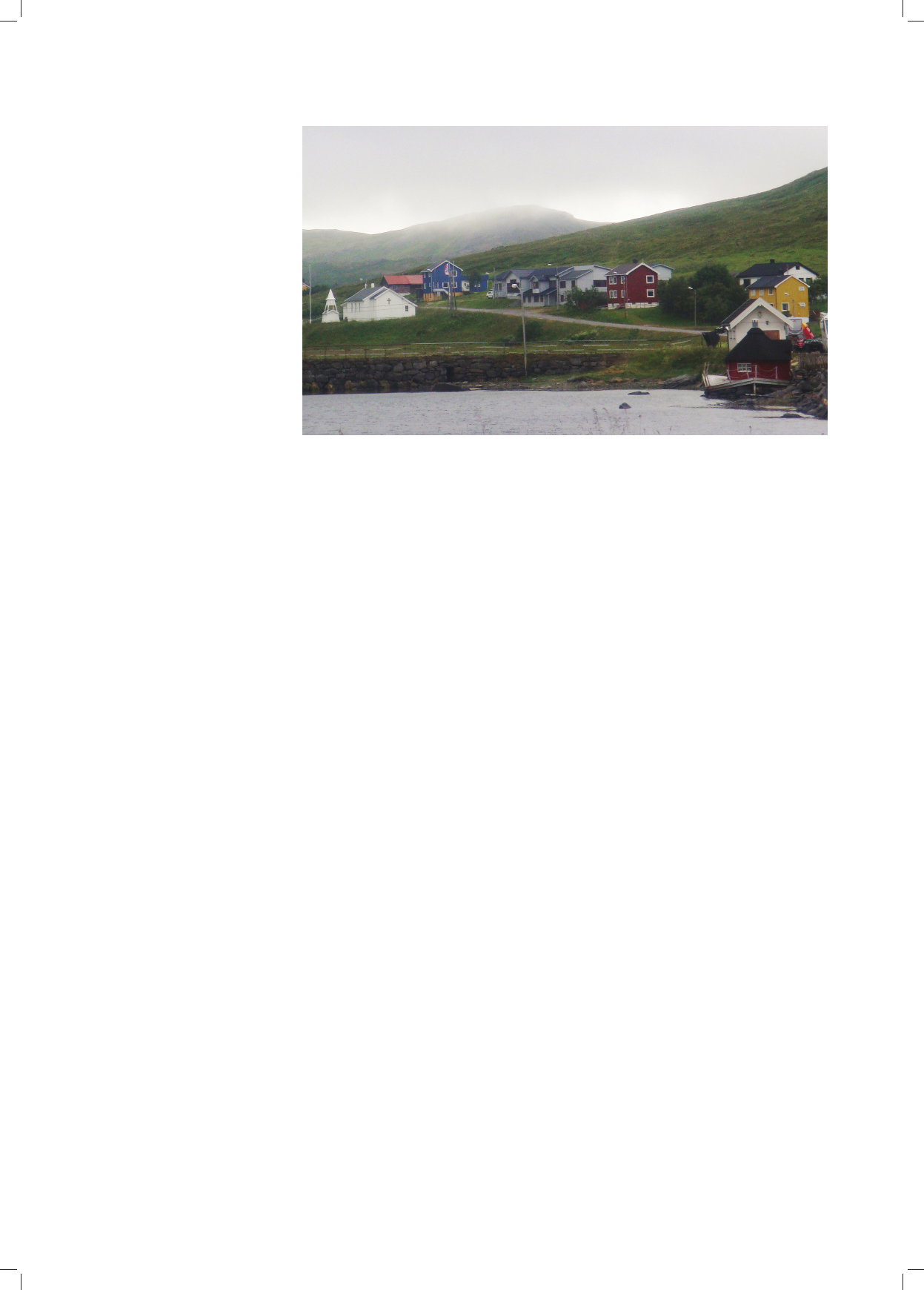

po gromem życie małych społeczności toczyło się w obrę-

bie jasno zorganizowanych przestrzeni. Proste w formie,

bielone domy o archetypowych, dwuspadowych dachach

tworzyły struktury mieszkaniowe o organizacji przes-

trzen nej klastrów. Część mieszkaniowa skupiała się zwy-

kle wokół centralnie usytuowanych funkcji: sakralnej –

kościoła/kaplicy lub użytkowej – rybackiego portu. Naj-

większym założeniem tego typu była arktyczna osada

Honnings våg położona na wyspie Magerøya. W jej bli-

skim sąsiedztwie usytuowane były również rybackie

wioski: Gjesvær, Kamøyvær i Skarsvåg, prezentujące

klastrowy układ w mniejszej skali. Wszystkie cztery zo -

stały po wojnie zrekonstruowane i odbudowane, uzysku-

jąc dodatkowe miano wiosek kulturowych i ekomuzeów.

Najbardziej spektakularnym z wymienionych przykładów

jest Honningsvåg. Gdy mieszkańcy osady powrócili do

niej po zakończeniu działań wojennych latem 1945 r.,

zastali morze gruzu z jedynym ocalałym, nietkniętym

obiektem, którym okazał się miejscowy kościół. Z nie-

znanych do dziś pobudek okupanci oszczędzili świątynię,

co w dużej mierze przyczyniło się do szybkiej reaktywa-

cji lokalnej społeczności. Świadomość, że zabytkowy,

pochodzący z 1885 r. drewniany obiekt ocalał, wystarczy-

ła, aby dać ludziom nadzieję na odbudowę doszczętnie

zniszczonej osady. Biały kościółek stał się miejscem

zakwaterowania dla pierwszych przybyłych do Honnings-

våg dawnych jego mieszkańców. Zorganizowano tu rów-

nież tymczasową kuchnię i piekarnię, które mogły wyży-

wić nawet 100 osób dziennie. Wokół kościoła z czasem

zaczęły powstawać drewniane baraki mieszkalne, w efek-

cie czego w Wigilię Bożego Narodzenia 1945 r. świątynia

mogła już być użytkowana wyłą

cznie do celów liturgicz-

nych i jako miejsce modlitwy. Fakt, że budynek ten ode-

grał ważną rolę latem 1945 r., pełniąc funkcję sypial ni,

magazynu żywności i kuchni dla małej społeczności, spra-

wił, że w późniejszym czasie uczyniono go głównym koś-

ciołem parafii Nordkapp, liczącej dziś ponad 3000 mie-

szkańców. Obecnie stanowi on symbol odwagi, na dziei

i jedności powracających po wojnie osadników. Współ-

cześni mieszkańcy Honningsvåg wyrazili również ostry

sprzeciw wobec planów gminy zastąpienia zabytkowego

obiektu większą formą architektoniczną. W rezultacie

tych protestów kościół pozostał, wybudowano natomiast

mo gące pomieścić znaczną liczbę wiernych nowe cen-

trum parafialne.

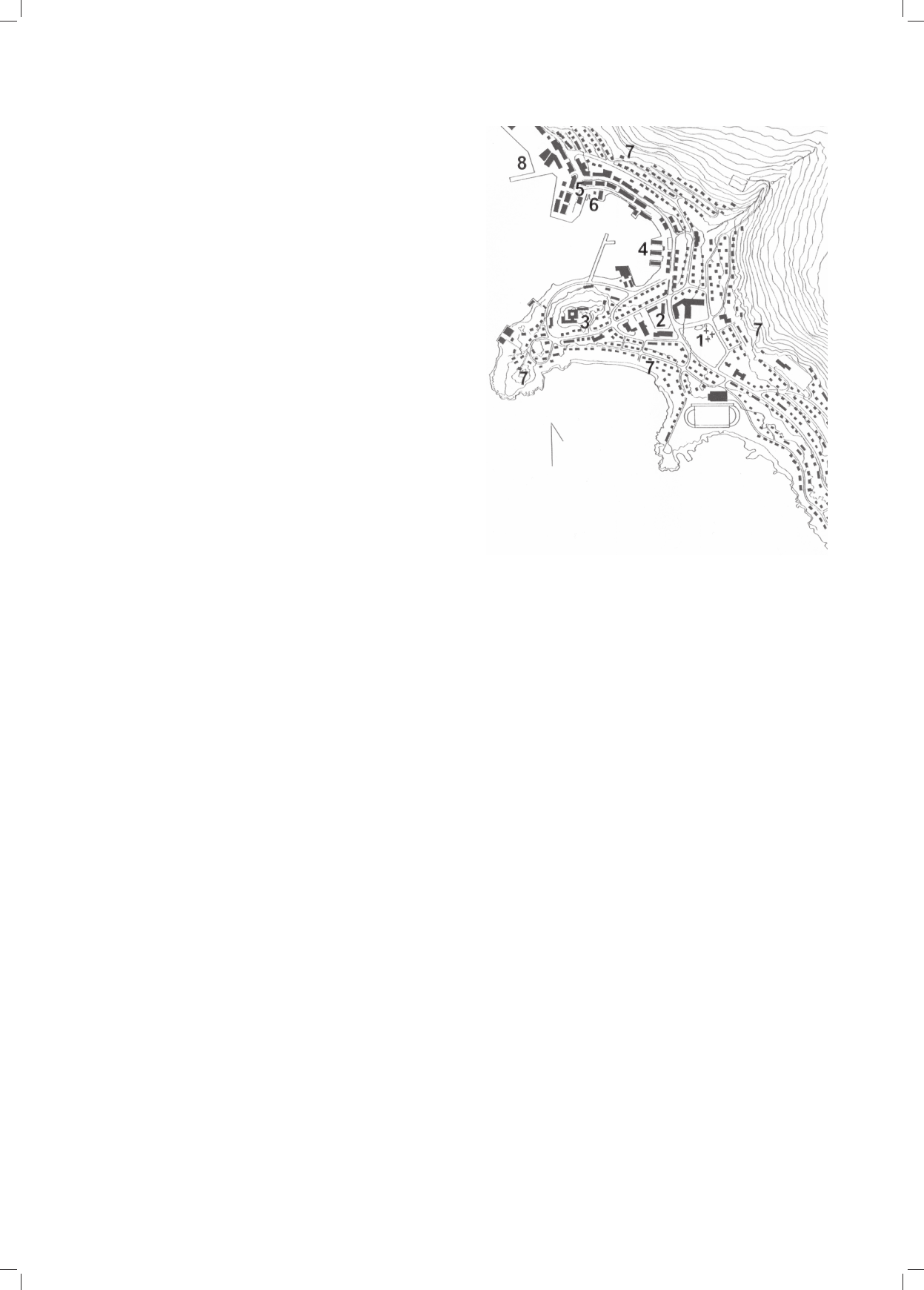

W 1947 r. rozpoczął się proces rekonstrukcji i odbudo-

wy Honningsvåg oraz innych zniszczonych miejscowo-

ści, który trwał nieprzerwanie do 1960 r. Inicjatorem tych

działań była specjalnie do tego celu powołana Organizacja

Rewitalizacji Obszarów Zniszczonych Wskutek Pożaru

(norw. Brente Steders Regulering – BSR), zaś głównym

architektem projektu został Per Lingaas. Znaczna część

obecnej struktury miasta powstała właśnie w tamtym

ok resie. Zasady planu odbudowy z lat 1947–1960 zostały

wykorzystane także w kolejnych etapach rozbudowy ca -

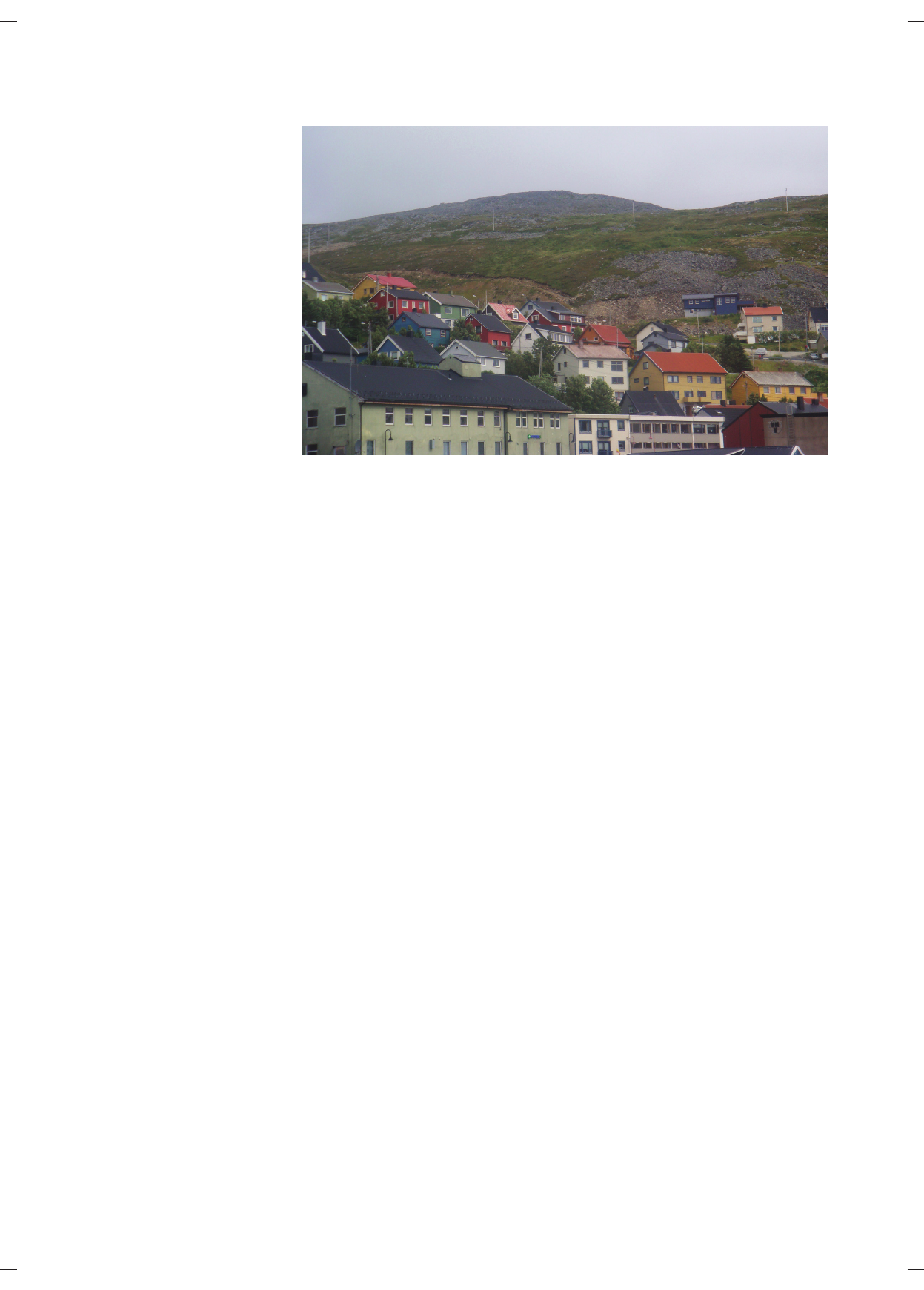

łego założenia. W efekcie tych działań ukształtowało się

obecne Honningsvåg, będące w znacznej części wierną

rekonstrukcją pierwotnej kompozycji: z dominującym na

wzgórzu drewnianym, bielonym kościółkiem i zorgani-

zowaną w klastrach zabudową mieszkaniową, skupiającą

trally located functions: ecclesiastical – church/chapel, or

services – fishing harbor. The biggest arctic settlement of

that type was that of Honningsvåg located on Magerøya

island. Other fishing villages: Gjesvær, Kamøyvær, and

Skarsvåg with cluster layouts on a smaller scale were lo -

cated nearby. After the war, all four settlements were

reconstructed and rebuilt as cultural villages and ecomu-

seums. Honningsvåg is the most spectacular of them.

When in the summer of 1945 the inhabitants of the settle-

ment returned after the war, all they found was a sea of

debris and only one original, untouched building – the

local church. For unknown reasons the occupiers spared

the church, which to a large extent contributed to quick

reactivation of the local community. The mere knowledge

that the historical, wooden building from 1885 survived

was enough to give people hope for the rebuilding of the

whole settlement. That little, white church was the place

where the first of Honningsvåg’s original inhabitants

stayed. A makeshift kitchen and a bakery were also orga-

nized there to feed as many as 100 people daily. In time,

some wooden dwelling barracks were constructed around

the church, and in fact on Christmas Eve 1945 the church

could be used only for religious purposes such as liturgy

and prayer. As this building played an important role in

the summer of 1945, when it was used as a sleeping place,

food storage, and a kitchen for the small community, later

it became the main church in Nordkapp parish, which

today has more than 3000 inhabitants. At present it is

a symbol of courage, hope, and brotherhood of the settlers

returning to this place after the war. The present inhabit-

ants of Honningsvåg expressed their strong objection to

the county’s plans to replace the historical building with

a larger architectural structure. As a result of these protests

the church remained untouched, and instead a new parish

center was built with room for many more congregants.

The process of reconstruction and rebuilding of

Honnings

våg

and other destroyed towns started in 1947

and continued until 1960. These activities were initiated

by the Organization for Revitalization of the Areas De -

stro yed by Fire (Brente Steders Regulering – BSR) which

was established especially for this purpose, and Per Lin-

gaas was the chief architect of the project. A large part of

the current structure of the town was developed at that

time. The principles of the rebuilding plan in 1947–1960

were applied also in following stages of the extension of

the whole development. In effect, those activities resulted

in the present time Honningsvåg which is to a large extent

a faithful reconstruction of its original composition: with

a wooden, little, whitewashed church dominating on the

top of a hill and residential buildings organized in clusters

around Vågen bay. Its uniformity, resulting from the tra-

ditional form of the houses – their sizes, plans, and roofs,

later painted in varied colors – was supposed to express

the integrated living conditions and their structure.

The reconstruction works in the area of Finnmark were

perfectly summarized in the text by Elisabeth Seip –

director of the Museum of Architecture in Oslo [1]. The

work by Ingrid Sætherø is a thorough study of the project

of the reconstruction and rebuilding of Honningsvåg and

nearby villages [2]. The process of developing the zone