Mural jako forma plastyczna /Mural as a visual form 43

The possibility to watch murals depended on their lo-

cation. Interiors and courtyards were available to the

elites. Pictures on outer walls could be viewed depending

on the character of a given space on a daily basis or on

holi days (sacred, ceremonial, representative spaces). How-

ever, most of the murals were in restricted access com-

plexes [1, p. 8].

One way or the other, on the one hand paintings had

specific compositional structures, while on the other – they

used simple methods of projecting space. These pro-

perties influenced compositional and artistic relations in

architectural or urban surroundings. The simplifications

and geometrization of the painted forms (ignoring aes-

thetic canons here) and a large share of frames organizing

compositions and divisions within pictures could have

resulted from spatial conditions, but at the same time it

influenced the compositional order in the environment.

The effect of this peculiar compositional unity was sup-

ported by other artistic forms which were located on the

planes of buildings because apart from murals-paintings,

many painted linear elements in the form of pedestals,

friezes, decorated pillars and in the form of ornamental

planes also appeared on walls.

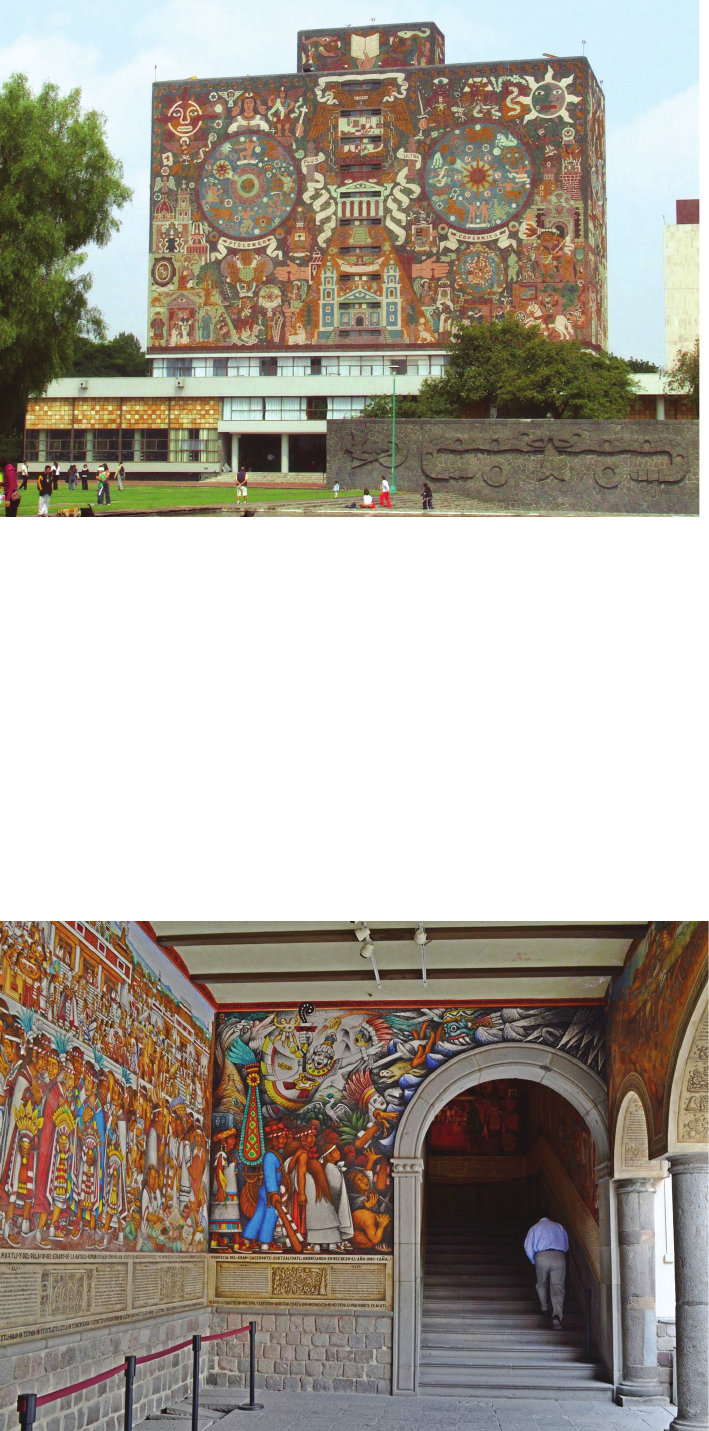

Examples of painting from this period are murals in the

Cacaxtla archaeological centre (state of Tlaxcala) which

belongs to olmeca-xicallanca culture (around the 5

th

–10

th

century AD). It was a religious, ceremonial and defensive

settlement. The main part of the town consisted of a raised

platform – Gran Basamento. The complex, which was

surrounded by walls, consisted of two small pyramids and

residences for the city’s elite. Many buildings had porti-

cos and decorations in the form of reliefs made of clay

and then polychrome. There were also numerous murals

outside and inside buildings [3].

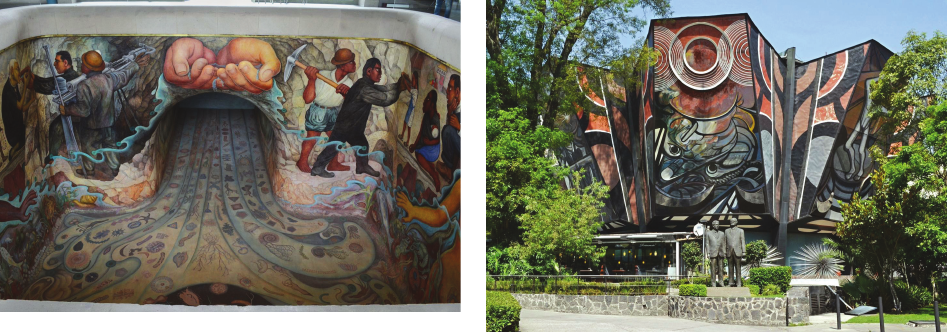

Similarly to other urban centres from this period, mu-

rals and other artistic forms created a significant compo-

nent of the spatial structure of Cacaxtli. In many places,

murals inside and outside buildings were preserved and

were connected compositionally with, for example, door

openings. Painting elements frame the passage on both

sides and decorative elements cover the jamb surfaces

(Fig. 1). In the so-called Red Temple (Templo Rojo)

a mural on the side wall of the stairs with a picture of

animals, plants and man at work was preserved. The com-

position, which is surrounded by an ornamental strip,

blends in with the geometry of the staircase space.

Among the preserved paintings there is a monumental

panorama of the battle depicted in two parts on a sloping

belt (talud) at the base of the temple. The mural is divided

into two halves by stairs. The horizontal composition of

battle scenes at the base of the temple cuts off the mass of

the building from the terrain. At the same time, the dy-

namic form of the pictures remains in opposition to the

static architectural structure (layout and proportions).

The flat scenes on the murals do not have any devel-

oped spatial plans (no depth illusion). However, the nar-

rative character of the performances and strong colour of

the images (battle scenes, figures of deities and fragments

of the environment) create a strong impression of spatial-

ity in painting categories. These artistic qualities are

Obrazy tego typu miały za zadanie zapisywać infor-

macje o fundamentach danej kultury. Służyły kapłanom

i władcom do utrwalania pryncypiów religii i historii pań-

stwa. Wiedza zapisana w formie obrazów była jednak zrozu-

miała dla wtajemniczonych elit. Pozostali mieszkańcy miast

odczytywali tylko najbardziej podstawowe informacje.

Możliwość oglądania murali uzależniona była od ich

lokalizacji. Wnętrza i dziedzińce dostępne były dla elit.

Obrazy na zewnętrznych ścianach mogły być oglądane

w zależności od charakteru przestrzeni na co dzień lub od

święta (przestrzenie sakralne, ceremonialne, reprezenta-

cyjne). Większość murali znajdowała się jednak w zespo-

łach o ograniczonym dostępie [1, s. 8].

Tak czy inaczej dzieła malarskie z jednej strony miały

określone struktury kompozycyjne, z drugiej – posługi-

wały się prostymi metodami projekcji przestrzeni. Te wła-

ściwości wpływały na relacje kompozycyjno-plastyczne

w architektonicznym lub urbanistycznym otoczeniu.

Uproszczenia i geometryzacja obrazowanych form (po-

mijając w tym miejscu kanony estetyczne) oraz duży

udział porządkujących kompozycje ram i podziałów we-

wnątrz obrazów mógł wynikać z uwarunkowań prze-

strzennych, ale jednocześnie wpływał na kompozycyjny

ład w otoczeniu. Efekt tej swoistej jedności kompozycyj-

nej wspomagały jeszcze inne formy plastyczne umieszcza-

ne na płaszczyznach budowli, albowiem op rócz murali-

-obrazów na ścianach pojawiało się wiele malowanych

elementów linearnych w postaci cokołów, fryzów, zdobio-

nych filarów oraz w formie ornamentalnych płaszczyzn.

Przykładem malarstwa z tego okresu są murale w oś-

rodku archeologicznym Cacaxtla (stan Tlaxcala) należą-

cym do kultury olmeca-xicallanca (ok. V–X w. n.e.). Była

to osada o charakterze religijnym, ceremonialnym i ob-

ronnym. Główną część miasta stanowiła wyniesiona plat-

forma – Gran Basamento. Otoczony murami zespół skła-

dał się z dwóch niewielkich piramid i rezydencji dla elity

miasta. Wiele budynków miało portyki oraz dekoracje

w postaci płaskorzeźb wykonanych z gliny, a następnie

po li chromowanych. Występowały też liczne murale na

zewnątrz i wewnątrz budynków [3].

Podobnie jak w innych ośrodkach miejskich z tego

okresu murale i inne formy plastyczne tworzyły znaczący

składnik struktury przestrzennej Cacaxtli. W wielu miej-

scach zachowały się murale wewnątrz i na zewnątrz bu-

dowli powiązane kompozycyjnie np. z otworami drzwi.

Elementy malarskie dwustronnie obramowują przejście,

a elementy dekoracyjne pokrywają powierzchnie ościeży

(il. 1). W tzw. Czerwonej Świątyni (Templo Rojo) zacho-

wał się mural na bocznej ścianie schodów z obrazem

zwierząt, roślin i człowieka przy pracy. Kompozycja oto-

czona ornamentalnym pasem wpisuje się w geometrię

prze strzeni klatki schodowej.

Wśród zachowanych malowideł wyróżnia się monu-

mentalna panorama bitwy zobrazowana w dwóch częś-

ciach na pochyłym pasie (talud) w podstawie świątyni.

Mural jest podzielony na dwie połowy schodami. Hory-

zon talna kompozycja scen bitewnych odcina masę bu-

dowli od terenu. Jednocześnie dyna

miczna forma obrazów

pozostaje w opozycji do statycznej

struktury architekto-

nicznej (układ i proporcje).