34 Daria Bręczewska-Kulesza

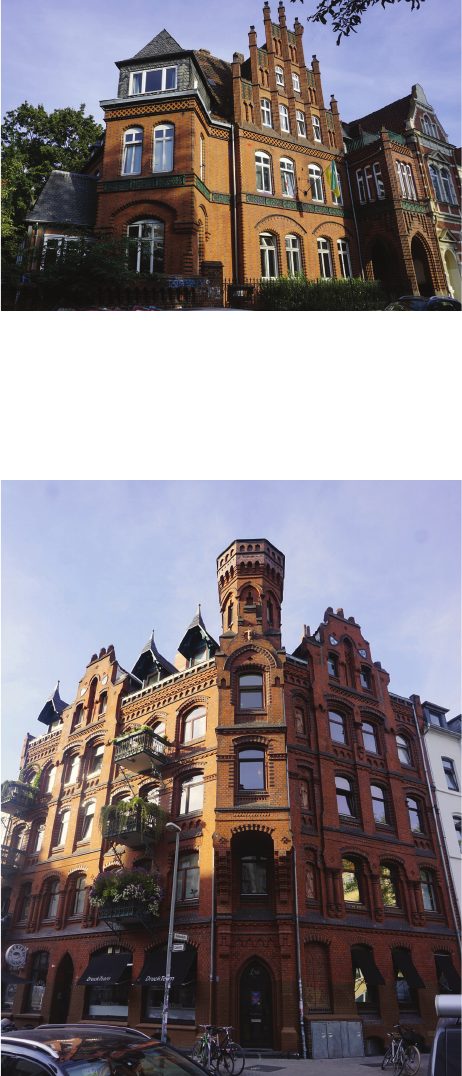

The second group of buildings, featuring elements rem-

iniscent of Gothic architecture, reected the contemporary

fashion for “picturesqueness”. The design of the building

at the intersection of Warszawska and Kazimierz Jagiel-

lończyk Streets was created by Berlin architects Hermann

Solf and Franz Wichards, who also designed almost the

entire western frontage of Kazimierz Jagiellończyk Street.

This type of solution can be found in the work of other

leading Berlin architects, such as Alfred Messel (Berlin und

seine Bauten, 1896, 216–217).

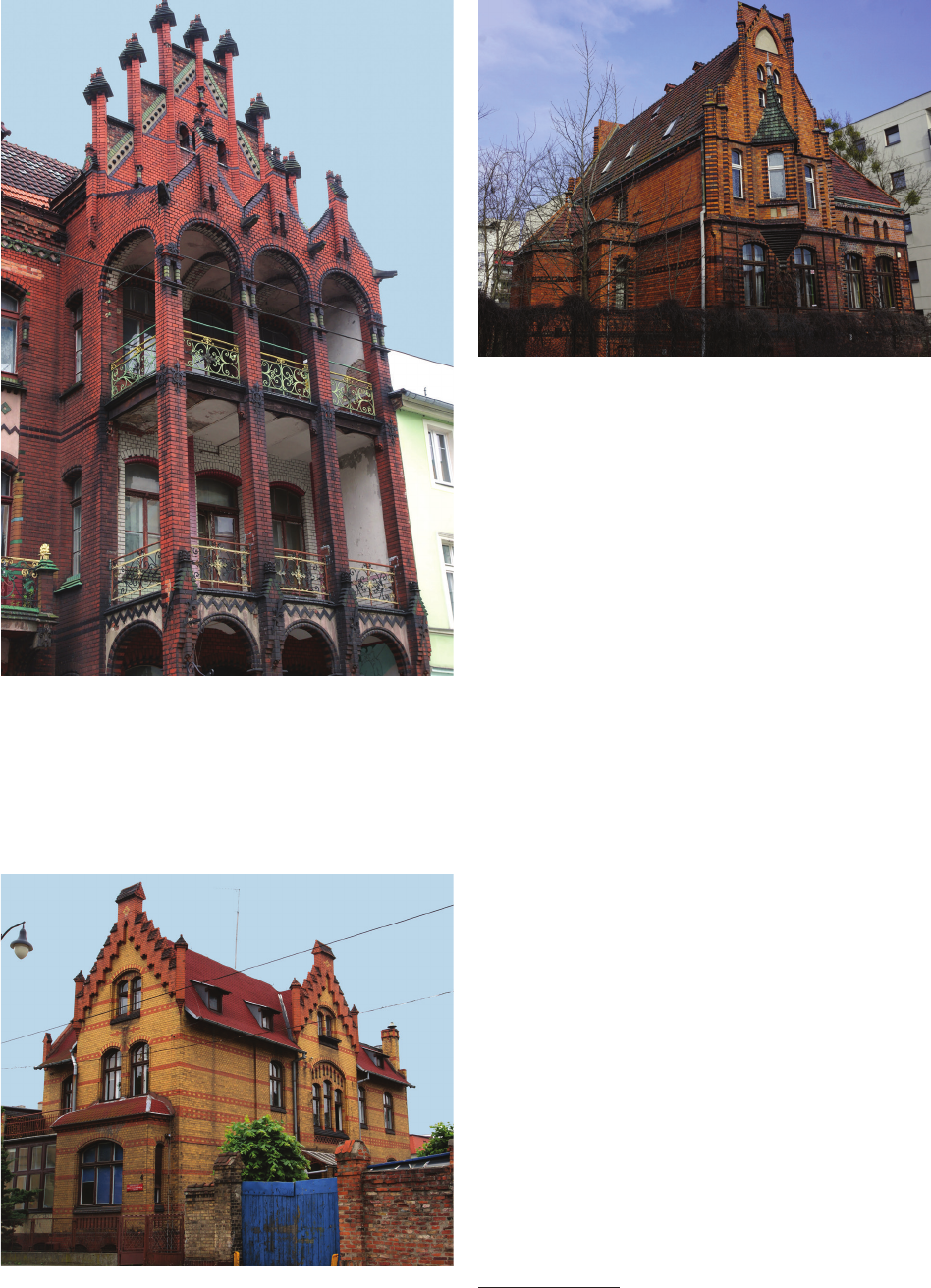

Other forms were used in the tenements on Sukienni-

cza and Szczytna Streets. The division into vertical panels

may have referred to burgher houses in Toruń, where it oc-

curred, but from the second storey onwards. However, the

“donkey’s back” or curtain arch nials used here are not

known from Toruń. Whether this is a deliberate reference

to late Gothic architecture or merely a coincidental stylisa-

tion is dicult to determine at present. This is a subject for

a separate, detailed study.

The third group comprises buildings with modest and

unremarkable designs, which can be found in many cities.

Such designs were often recommended to less auent cli-

ents in pattern books and architecture textbooks.

Analysing the historical context has enabled us to

study how the importance of Gothic tenements changed

in Toruń’s residential development in the 19

th

century. The

city was a large, prosperous centre in the Middle Ages,

wealthy enough for independent local housing trends to

emerge, as research has shown. Wealthy merchants built

residences here to demonstrate their wealth and the reliabil-

ity of their businesses. Subsequent eras have left their mark

on Toruń’s Gothic tenements, with many of them being

rebuilt. In the 16

th

century, the upper storeys were no lon-

ger used for storage and the façade decoration was altered.

During the Baroque period, Toruń’s tenement façades were

enriched with stucco decorations featuring oral motifs and

Italian stylistic elements.

In the 19

th

century, Toruń was a medium-sized provincial

town. Although it developed slowly, demographic growth

continued to create an increased demand for housing. Fur-

thermore, the city was enclosed by fortications for a long

time, which hindered urban development. Many dilapidat-

ed buildings were demolished. New, larger houses were

then built on connected plots of land in their place. A lack

of legal protection for townhouses, coupled with economic

factors, led to the conversion of numerous buildings with

Gothic origins. The demand for rental housing and com-

mercial premises led to conversions and alterations. Of the

few surviving tenements, some made distant references

to their medieval predecessors (Prarat, Zimna-Kawecka

2020, 19–21). According to Rymaszew ski (1966, 112),

several dozen historic tenements were signicantly rebuilt

at this time. In terms of functionality, the Gothic tenements

were not suitable for conversion into comfortable, modern

dwellings that met 19

th

-century standards. Consequently,

the historic bourgeois tenement houses in Toruń were not

valued by the city’s residents at the time. They were not

particularly suited to modernisation, and most were in poor

condition. Unsurprisingly, Neo-Gothic was not popular in

the town that is now considered a centre of Gothic archi-

tecture. In the eyes of its 19

th

-century inhabitants, it can

be assumed that the rebuilt and dilapidated townhouses

were not attractive models to follow, unlike the works of

the Hanoverian school. Today, after years of research and

ongoing restoration work, the town presents a very dier-

ent image.

The following questions remain: what were the reasons

behind investors choosing Neo-Gothic stylisations and

where did these patterns come from? As previously men-

tioned, original Neo-Gothic designs among Toruń’s resi-

dential buildings were few and far between. Both Gothic

and 19

th

-century buildings served a representative function,

but other stylistic forms were considered more represen-

tative in both periods, hence the Neo-Gothic inspirations.

The investor who opted for this style probably wanted to

make his house stand out from the surrounding buildings.

This was successful, as evidenced by the reaction of the

local press (Pszczółkowski 2021, 274, 275).

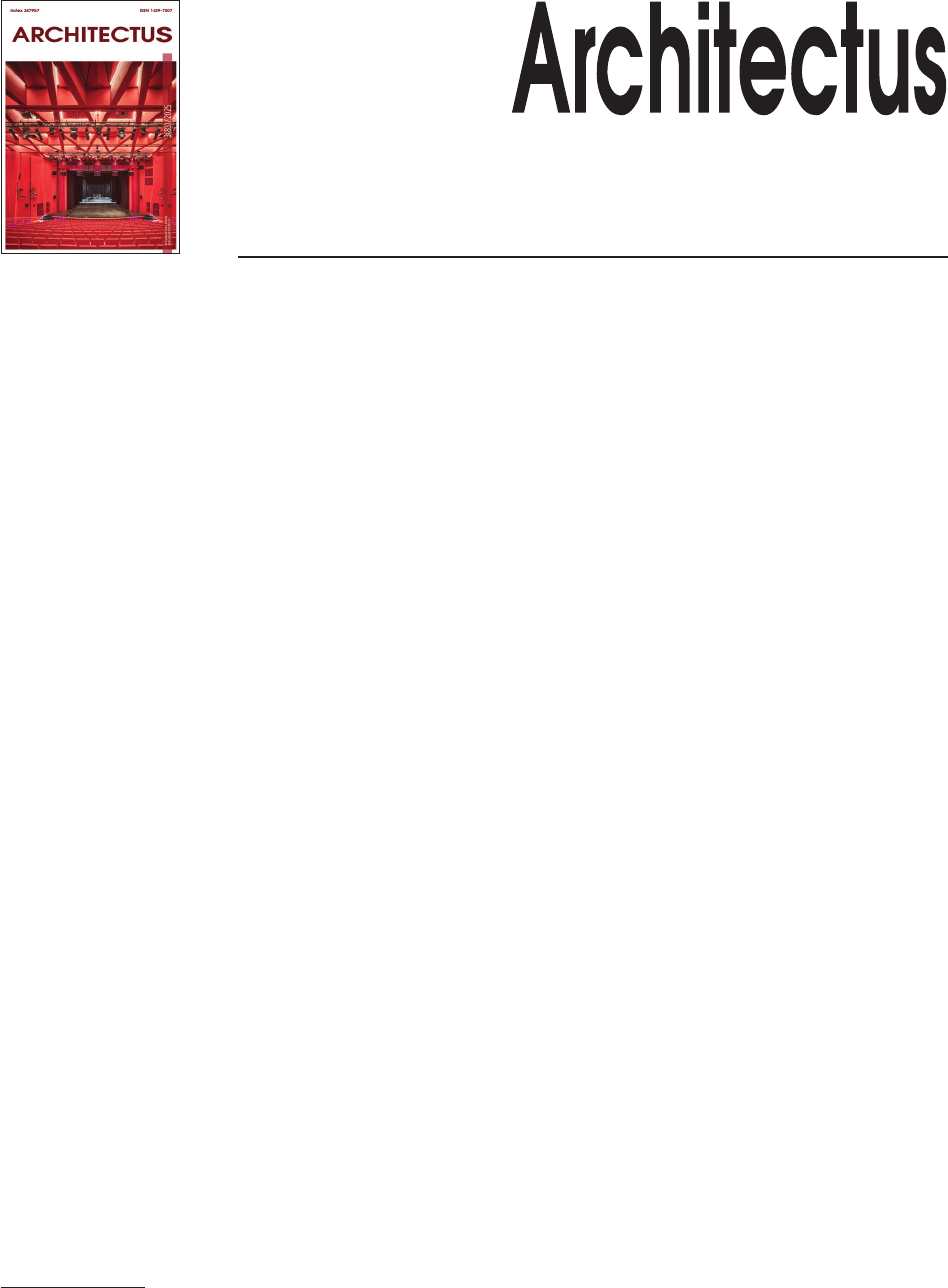

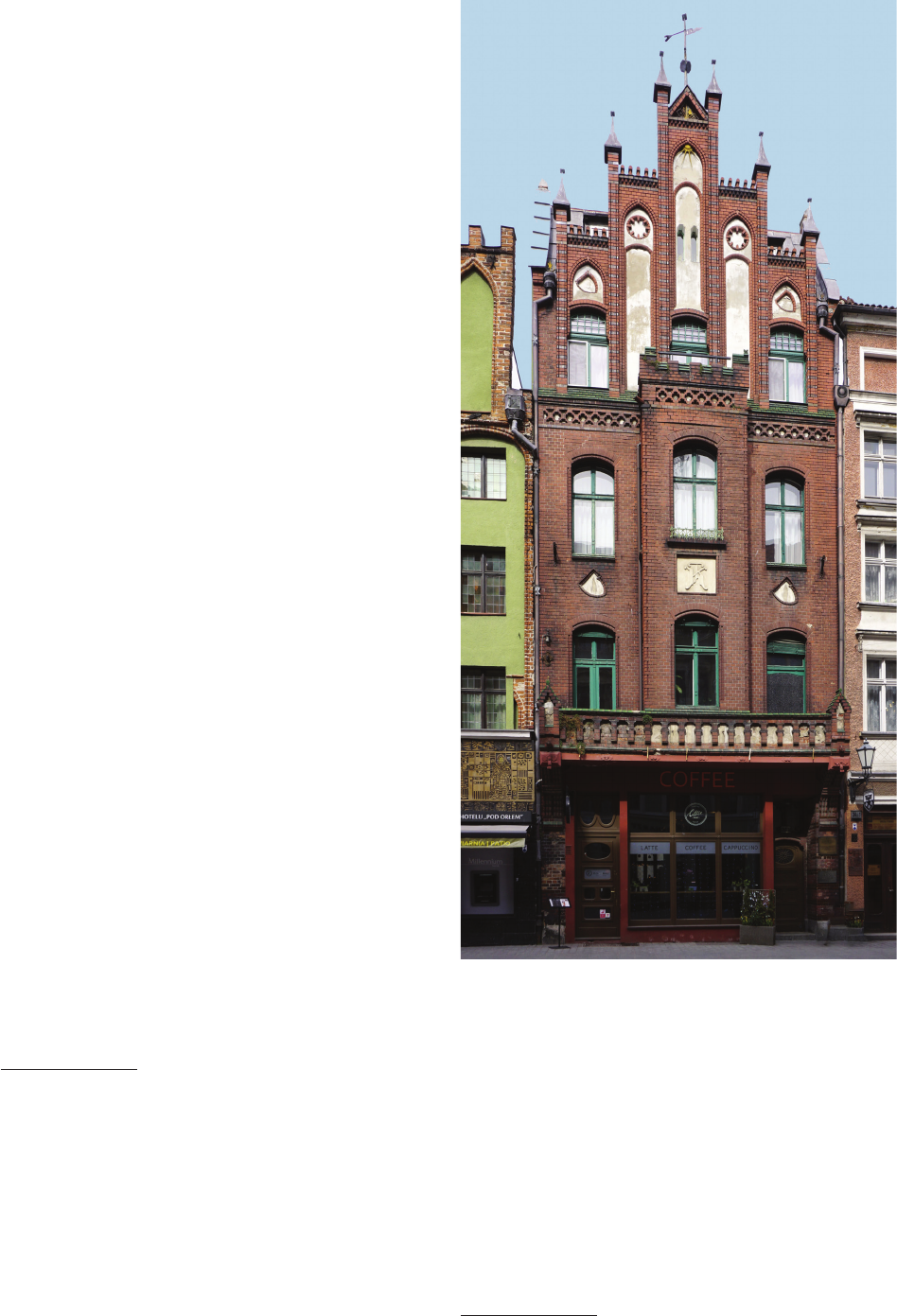

Who were the investors? The tenement house at 15 Sien-

kiewicz Street belonged to Georg Soppart, a master mason

and construction entrepreneur who was active in Toruń.

It undoubtedly served as a showcase for his company.

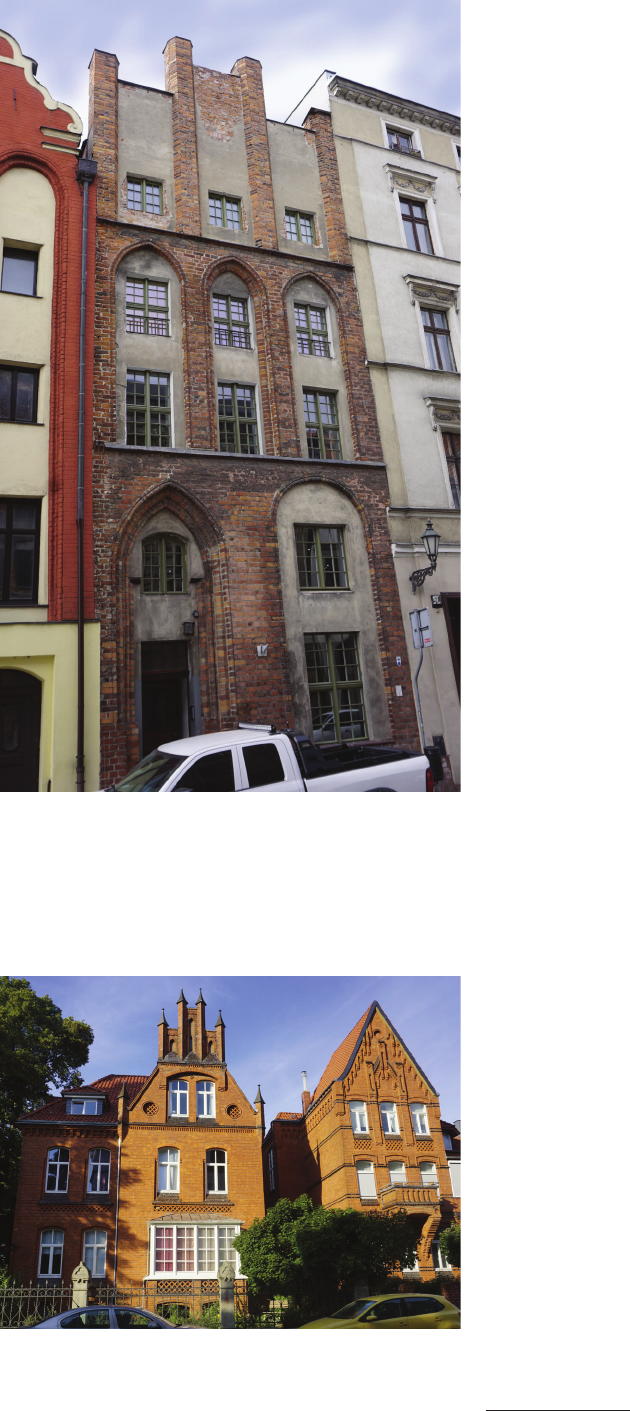

Georg Plehwe, also a master mason, owned the villa at 85

Krasiński Street. The building’s original form showcased

the contractor’s skills. The most subdued of the described

properties, the villa at 4 Sienkiewicz Street, belonged to

Emil Dietrich, a town councillor and owner of a large

family trading company. The last property was owned by

Daniel Sternberg, a merchant. The building, with its exten-

sive shop and warehouse spanning the entire ground oor,

was a striking feature of the Szeroka Street development,

attracting customers with its unusual façade. All of the in-

dividuals mentioned were active participants in public life,

embracing a broad-minded approach, and were likely to

have recognised attractive architectural trends. Residents

of Toruń maintained close ties with Berlin, which, as the

capital at the time and a thriving architectural centre, was

a place where emerging trends intersected and compet-

ed. They probably travelled there “on business”, viewing

buildings and occasionally commissioning projects. Local

architects and builders were also members of nationwide

associations of engineers, architects, and builders. This al-

lowed them to follow the works of their colleagues in other

cities and regions.

In addition, the new Toruń post oce building was con-

structed in the early 1880s, on the market frontage. The

building’s design was created by Johannes Otzen, an ar-

chitect who was already working in Berlin at the time. He

was a graduate of the Hanoverian School and a pupil of

Hase (Kucharzewska 2002, 90). The post oce building

aroused great interest and could have inspired Neo-Gothic

designs. One such unrealised project was a tenement house

commissioned from Otzen by winemaker Johann Schwartz

and planned for Chełmińska Street (Pszczółkowski 2021,

275; Kucharzewska 2002, 89). As the architect wrote in the

Deutsche Bauzeitung (Otzen 1881, 580), the tenement’s

layout was designed in the Hanoverian style, analogous to

the forms of the post oce building.

The other most common route of pattern penetration

was through the professional press and building hand-