98 Jerzy Uścinowicz

is sacrilege directed at Heavenly Jerusalem, of which it is

a preguration.

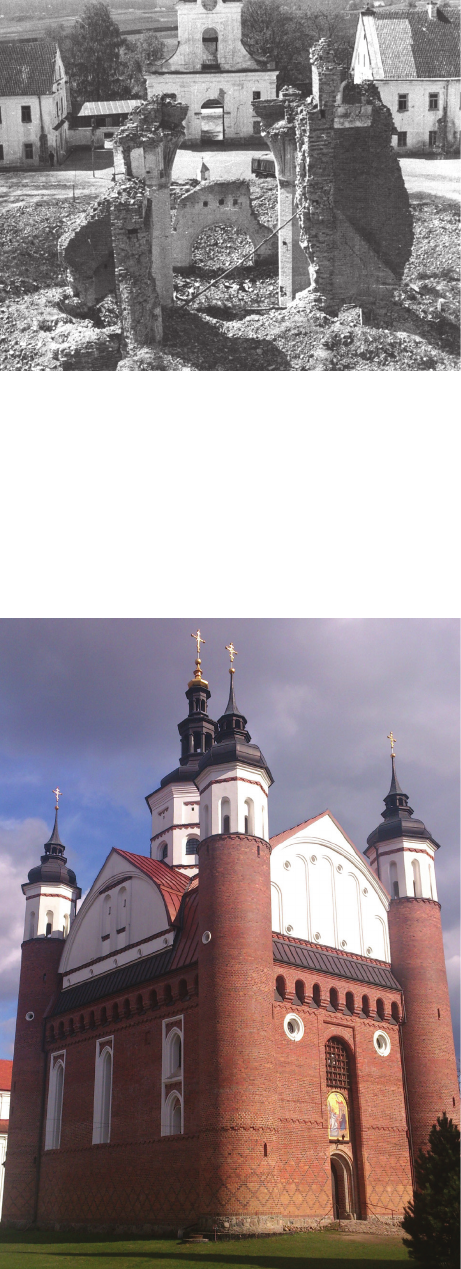

Ruined temples are an ethical, religious and social prob

-

lem. It is also an age-old problem of architecture. After ev-

ery war, hundreds of them remain. War tears away part of

their substance – it must be integrated, given new life, and

sometimes reconstructed from scratch. Evidence of their

original forms is often lacking. However, the spirit of the

place remains in them. There are several dozen such temple

ruins in Poland. In Ukraine, Syria, Turkey, Iraq, Egypt and

the Balkans, there are hundreds, perhaps even thousands.

Much has changed today in the spiritual values of reli

-

gious people. In Africa and the Middle East, temples are

being demolished or converted into places of worship for

other religions, as in the past, but this is also happening

in the West

1

, which is closer to us. Aggression towards

sacredness is escalating, ranging from complete denial of

spirituality and secularisation to religious proselytism and

religious war. The forecasts are alarming. The magazine

Observatoire du Patrimoine Religieux reports that of the

approximately 100,000 churches in France today, including

45,000 parish churches, 5,000 to 10,000 temples managed

by municipalities, i.e., 5–10% of all temples, will be demol

-

ished by 2030. The situation will be similar in Germany,

the Netherlands, Great Britain, Ireland, Austria and even in

very religious Italy. The Archbishop of Utrecht, Cardinal

Willem Eijk, has publicly announced the closure of a thou

-

sand churches in the Netherlands. In Western European

countries – as was the case not so long ago in the USSR,

where 70,000 temples

2

were demolished during the com-

munist era – churches are being systematically demolished

or converted into restaurants, discos, warehouses, hotels

and shops, or even brothels and toilets.

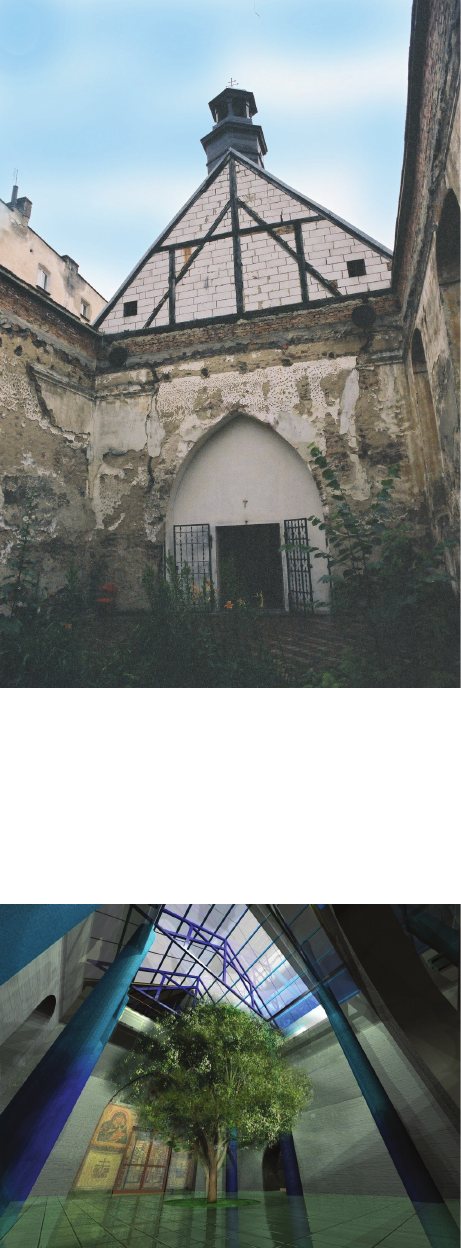

This is the case today in the West, and it was and still is

the case in Poland. We have lost dozens of temples forev

-

er, many have been desecrated and lie in ruins. A bizarre

event, showing a lack of respect for “other” sanctity, was

the establishment of the “Rink Weis” disco in the beautiful

Neo-Gothic Evangelical temple in Wieldządz in the 1990s.

A drink bar was set up in place of the altar, and a toilet was

installed directly below it, in the crypt under the altar. In

the middle of the nave, a huge stage with a pool for sex

(less perverse here, but more so in a separate room above

the porch)

3

was installed. The new sanctuary was even con-

secrated by a priest, who was probably unaware of what

was going on. A similar fate befell the beautiful Orthodox

church in Sokołowsko, located in a spa park, which was

converted into a dacha after World War II. Its dome, sym

-

bolising Jesus Christ, along with the cross, was cruelly cut

1

A notorious example of this was the desecrated and ultimately

demolished 19

th

-century Neo-Gothic church of Saint-Jacques d’Abbe-

ville in France in 2013. During its demolition, sacrilege took place – the

destruction of sacred sculptures and paintings. The cross of Christ was

thrown away with the rubble into a rubbish bin.

2

In 1914, there were 54,174 Orthodox churches, 25,593 chapels

and 1,025 monasteries in the Russian Empire. By 1987, only 6,893 chur-

ches (12%) and 15 monasteries (1.5%) remained in the USSR (Kesler

2021).

3

The information comes from the author’s site visit to Wieldządz

and interviews with witnesses to the events.

o so as not to arouse unnecessary associations. Inside,

an apartment was built, complete with a toilet. This is not

a unique case. The same thing happened on Holy Mountain

Jawor, where the Lemko religious sanctuary was converted

into a toilet for Border Guard soldiers. Is this right?

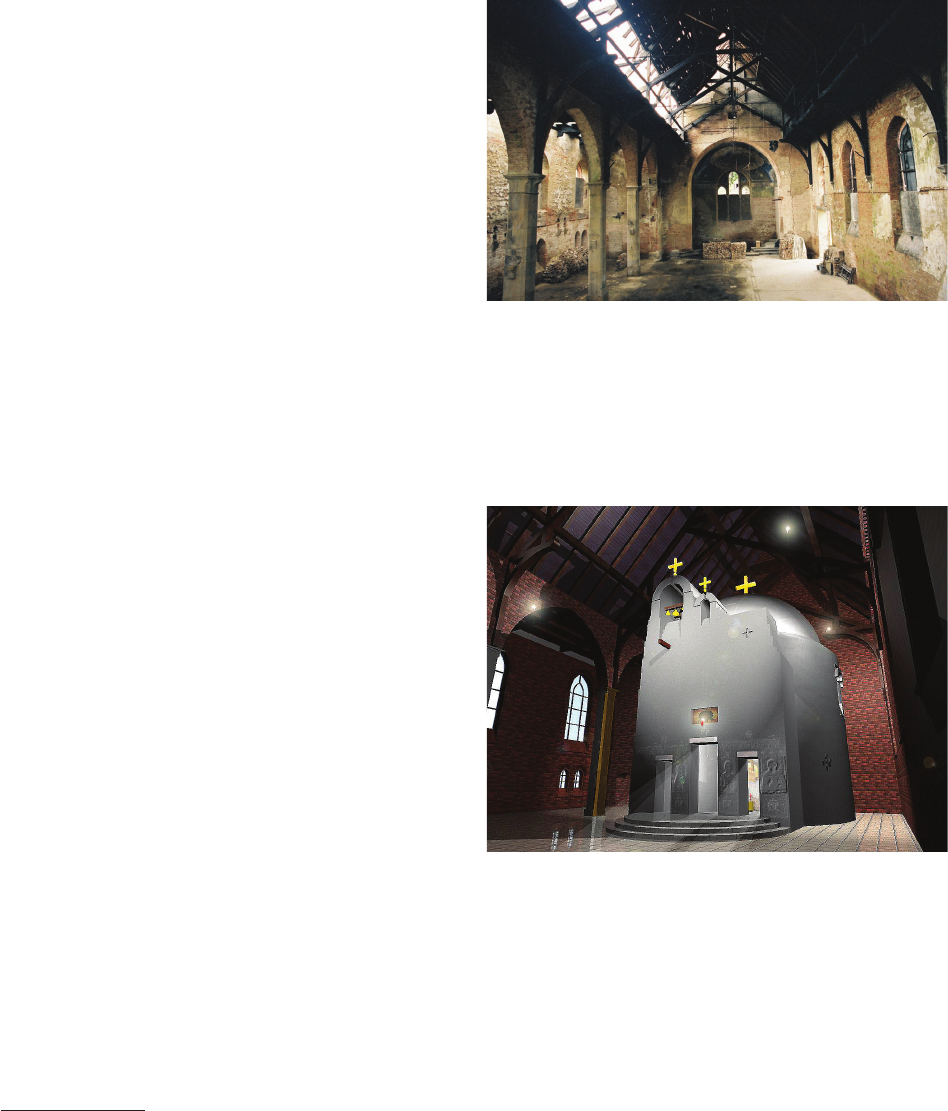

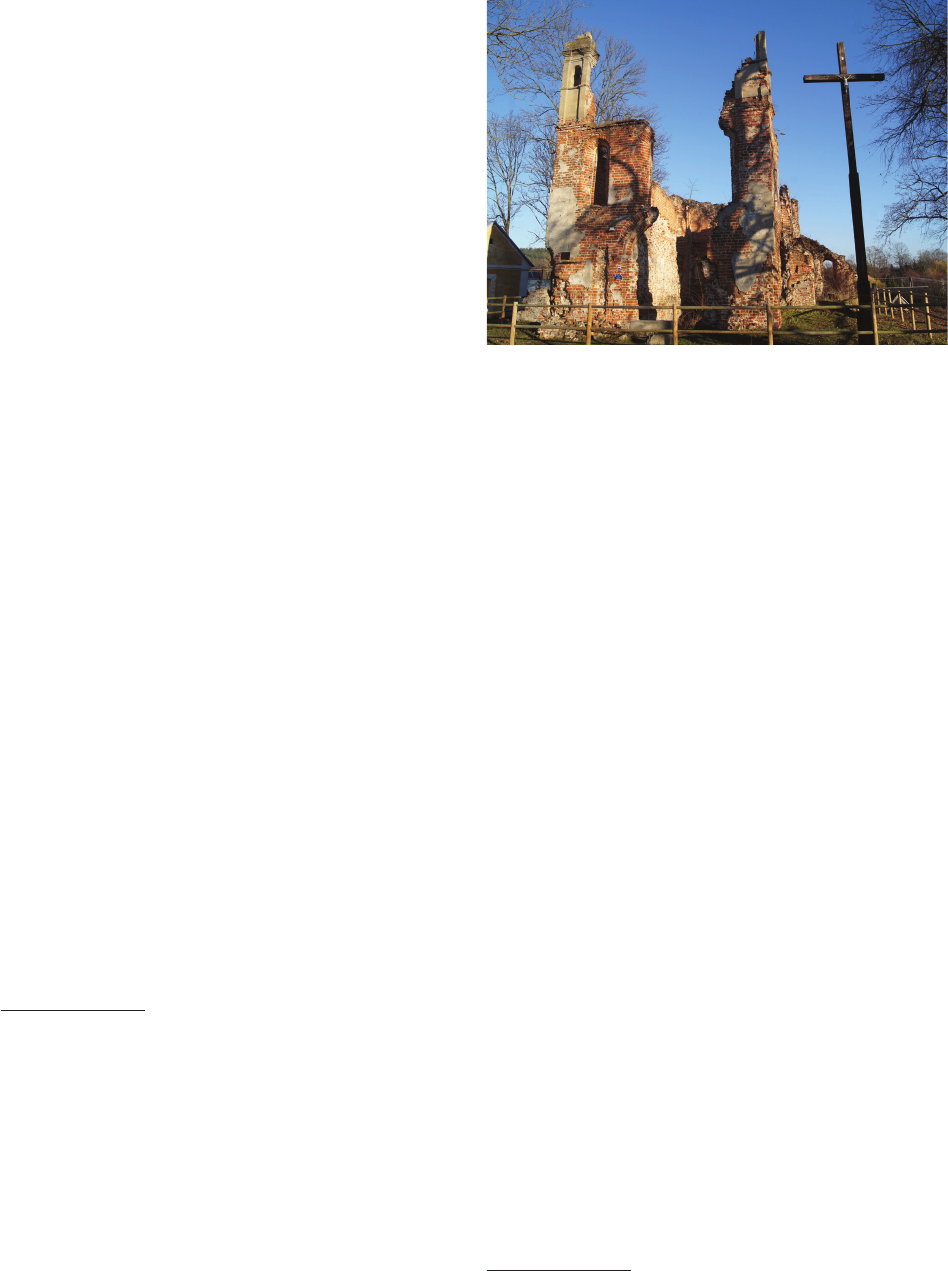

There are still dozens of such mutilated, desecrated tem-

ples, “silent witnesses”. Among them are former Roman

Catholic and Evangelical churches in Chodel, Jałówka, Miel

-

nik, Pisarzowice, Rumia, Wałbrzych, Wojnowice, Żeliszów,

Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches in Babice, Berezka,

Huta Różaniecka, Kniaziach, Krywe, Miękisz stand in in

-

creasingly less “permanent ruin”. They are waiting for better

times. Will they come?

Spirit and matter

Conicts between the profane and the sacred have always

existed, inscribed in the genetic code of this world. They in

-

tensied in the face of proselytism, religious wars and revo-

lutions. Today, they are rationally explained by the progress

of civilisation, especially the secularisation of life and its

subordination to the laws of economics, the glori cation of

material values and the dictates of money. But this conict

is also evident in culture. It manifests itself in art history

and in the protection and conservation of monuments.

One of the postulates of the 1964 Venice Charter is to aban-

don restoration. This reinforces the rather strict ban on recon-

struction. Article 15 states that […] all reconstruction work

should however be ruled out “a priori”. Only anastylosis,

that is to say, the reassembling of existing but dismembered

parts can be permitted (Karta Wenecka 1964). The document

recommends respecting the original substance of the struc

-

ture and material of the historic building, and all newly added

elements should be distinguishable from the original

ones.

Where it is impossible to use traditional technologies corre

-

sponding to the object, the use of new technologies that have

been tested in modern times is permitted. It also calls for the

protection of fragments of the building from all stages of its

construction, categorically prohibiting the replacement of

original building elements with faithful copies.

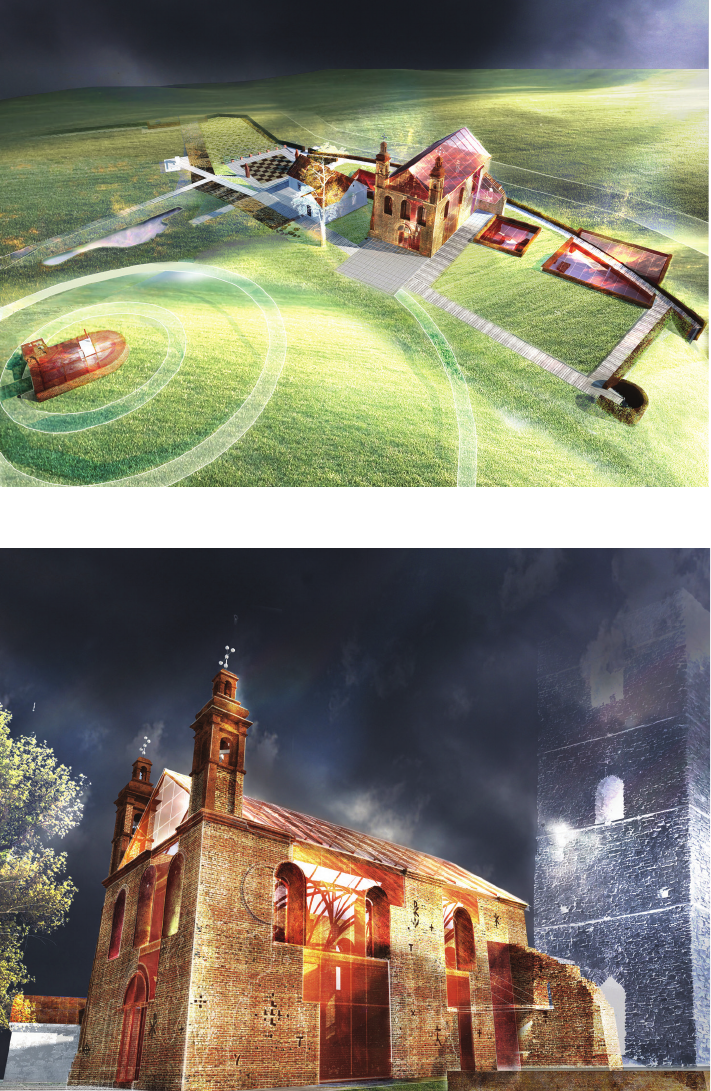

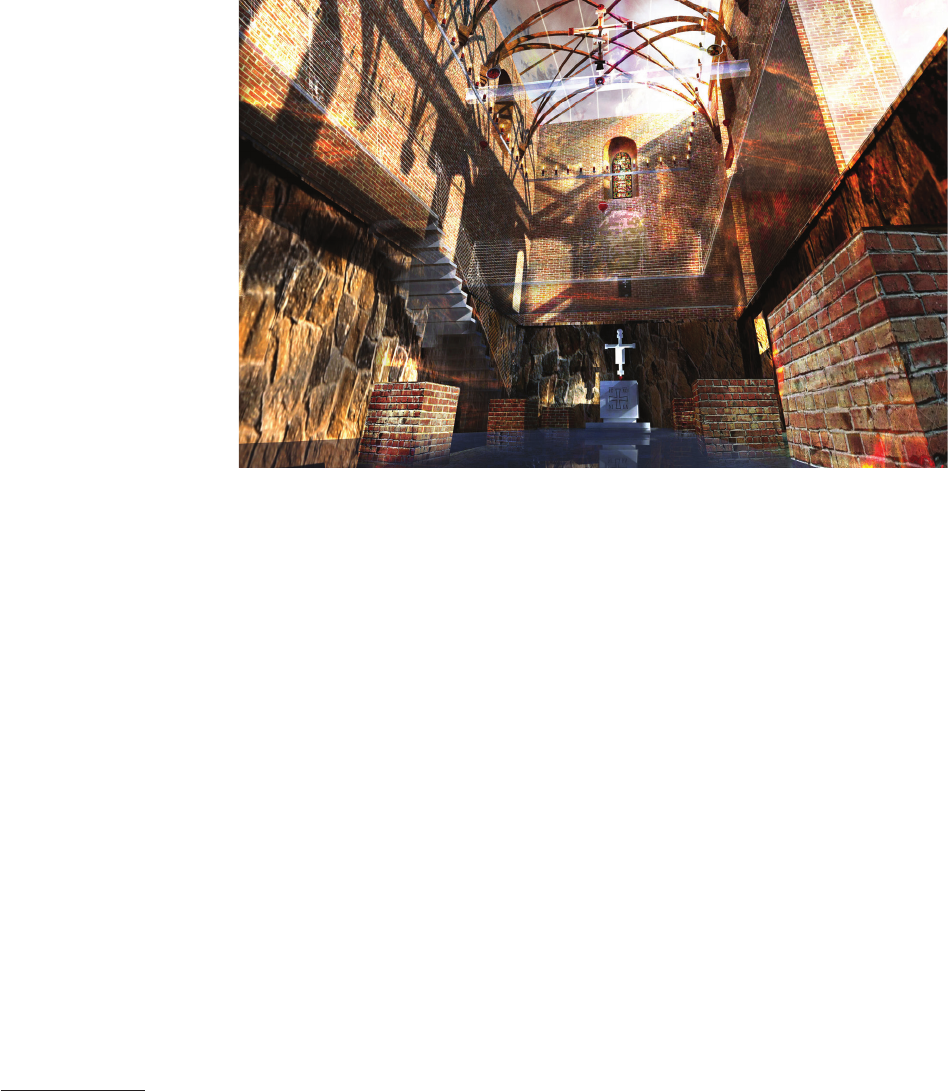

The 2012 Charter for the Protection of Historical Ruins

clearly states that ruins should be recognised as fully- edged

monuments (Karta Ochrony… 2012). But is recognising ruins

as fully-edg ed monuments (even though they will never be

fully so) and providing ad hoc assistance in legal protection

and conservation sucient? Is this all that is needed in view

of the possibilities that arise with the development of civil

-

isation? New methods of creation, contemporary materials,

techniques and technologies, especially virtual ones, oer the

possibility of moving to a dierent level of artistic activity and

visual reception, variable in time and space. Doctrinal provi-

sions are important; they serve to legally protect historic sub-

stances that are our heritage, defend the authenticity of forms

and historical truth, and counteract their falsication. But

does the sacredness of a monument exclude it from the pro

-

cedures applied in all other categories? Does it not require ac-

tions appropriate to its status and value? Can we act dierent-

ly than before in the creation of “sacred” ruins from the dead?

In some architectural monuments, material values play

a secondary role. They merely serve as intermediaries in