6 Krystyna Sulkowska-Tuszyńska

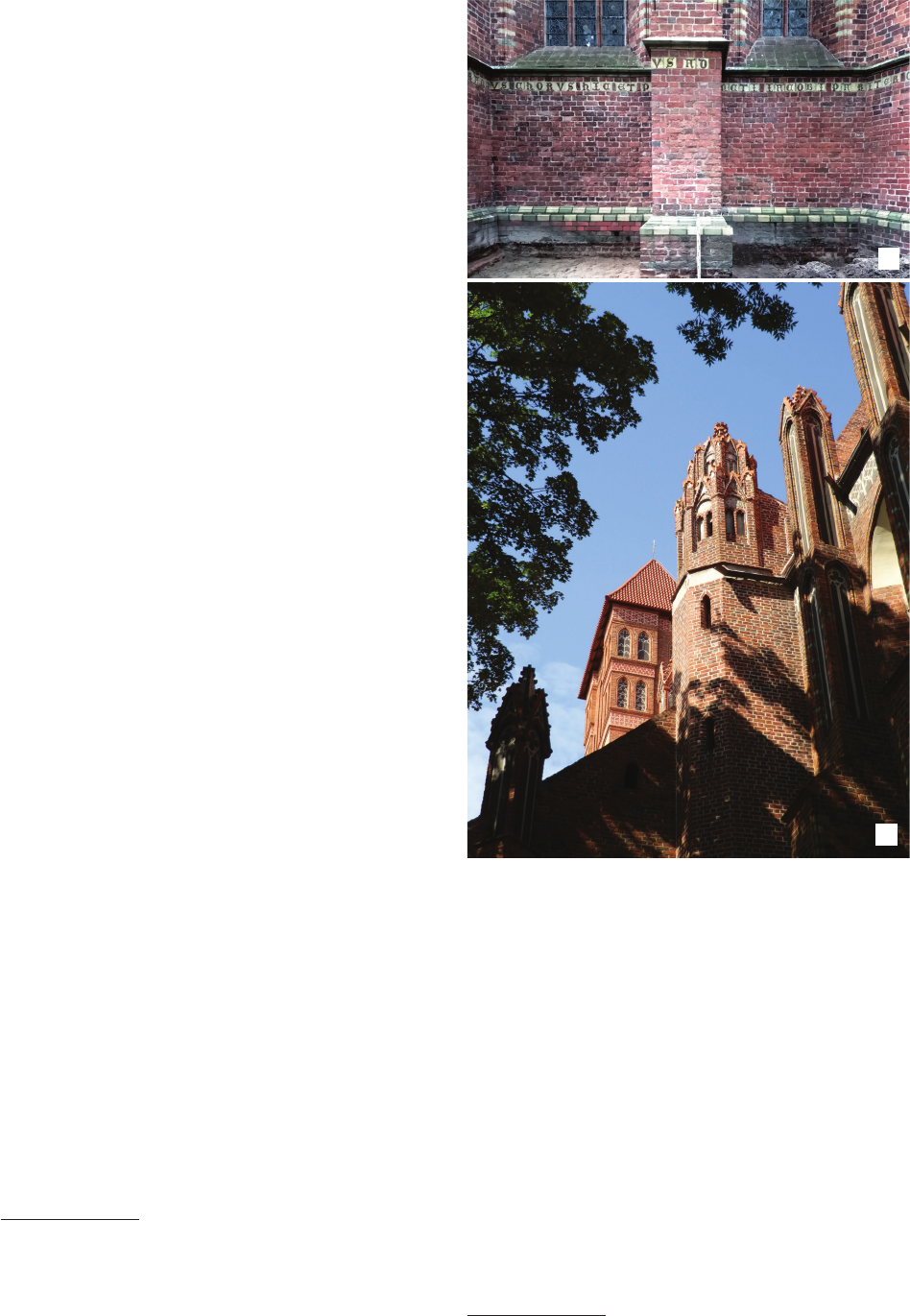

on a quadrangular plan with a cut corner – while also being

a pillar of the supporting arch stretching over the sacristy

(Figs. 3B, 1A)

6

. To the north and south, the naves are

anked by shallow chapels nestled between buttresses. The

smallest and newest chapel, adjoining the western wall of

the nave, is located next to the main portal (Figs. 1A on the

right, 1B, 2B). Soaring over the entire complex and the

city, the massive tower, on the axis of the complex, was

built into the western bay of the nave. It is anked on the

north and south by two rooms that extend the side naves.

Here is the main portal of the church. Near the tower, on

the north side, is a Renaissance plastered porch with two

portals leading into the interior (Fig. 2B).

The history of St. James’s Church is crucial for consider-

ing the circumstances of architectural alterations. It was

founded by the Teutonic Knights rather than the townspeo-

ple, a fact that has been and continues to be a subject of de-

bate (Błażejewska 2013), in the mid-14

th

century, the

church, together with the hospital and school, was handed

over by the Teutonic Knights to the Cistercian nuns of Toruń

under the patronage of the Teutonic Knights (Błażejewska

2022, 86–98). Until the mid-16

th

century, Catholics prayed

in this church; from 1557, for 110 years, it was occupied by

Protestants. Since 1667, it has been Catholic again.

With the advent of the Reformation, already in the 1520s

and 1530s, new religious trends reached Toruń, leading to

the Lutheranization of the townspeople and the city in the

middle of the century (Cackowski et al. 1994)

7

. Protestants

took over St. James’s Church, removing many furnishings,

rearranging the interior and whitewashing the walls to cov-

er the polychromes. Over time, the side altars were likely

taken apart and perhaps the ooring was replaced

8

. The

abandoned monastery was converted into a warehouse and

granary. During the, so-called, Swedish Deluge, the church

suered shelling and robbery of the bells. Only in 1667

were the nuns allowed to return to the reclaimed church

and old monastery

9

. The Protestant city authorities distrust-

ed the monastic orders and were hostile towards Catholics,

so it became necessary to create a cloistered area near St.

James’s Church through construction of a corridor to en-

sure safe passage between the church and the monastery

for the nuns. In the 18

th

century, the chancel was surround-

ed by new monastery buildings

10

.

In 1833, the Prussian occupying authorities forced the

Cistercian-Benedictine nuns to abandon their church and

6

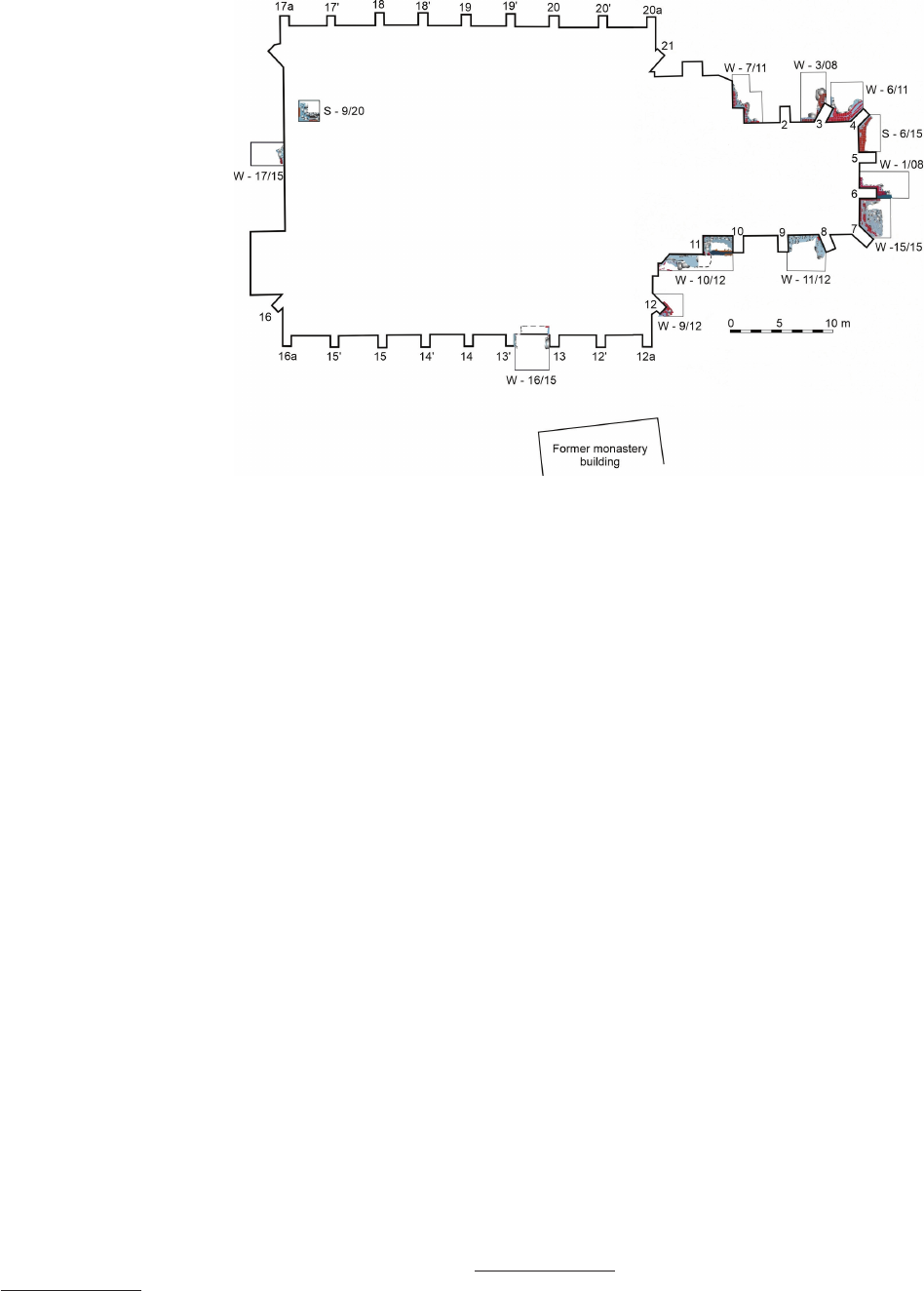

The nave and sacristy were surrounded by supporting arches ex -

tending from the main walls to the buttresses. As a result of the con struc-

tion of chapels and the raising of the roof, these arches were obscured.

The arch extending onto the sacristy’s turret is the only visible element

of this structure today.

7

The privilege of King Sigismund Augustus of December 12, 1558,

allowing the preaching of the Gospel according to the Augsburg De no-

mination (Cackowski et al. 1994).

8

This is merely a supposition. Inside, two fragments of such tiles

were found in two of the surveys.

9

At the same time, the nuns lost their convent on the Vistula

River, which was destroyed by the Swedes.

10

This is indicated by preserved iconographic sources – plans of

Toruń from the 18

th

century and the results of archaeological research at

the contact point with the old monastery building (Cicha 2010; Sul kow -

ska-Tuszyńska, Cicha, 2010).

convent, thus beginning the dissolution of the monastery.

Several years later (1837), the Prussian authorities informed

the parishioners of their intention to close down the ceme-

tery, prohibiting burials in there. To this day, St. James’s

Church serves as the parish for the former Nowe Miasto

Toruń and the surrounding neighborhoods (Sulkowska-

Tuszyńska 2022a, 330, 331).

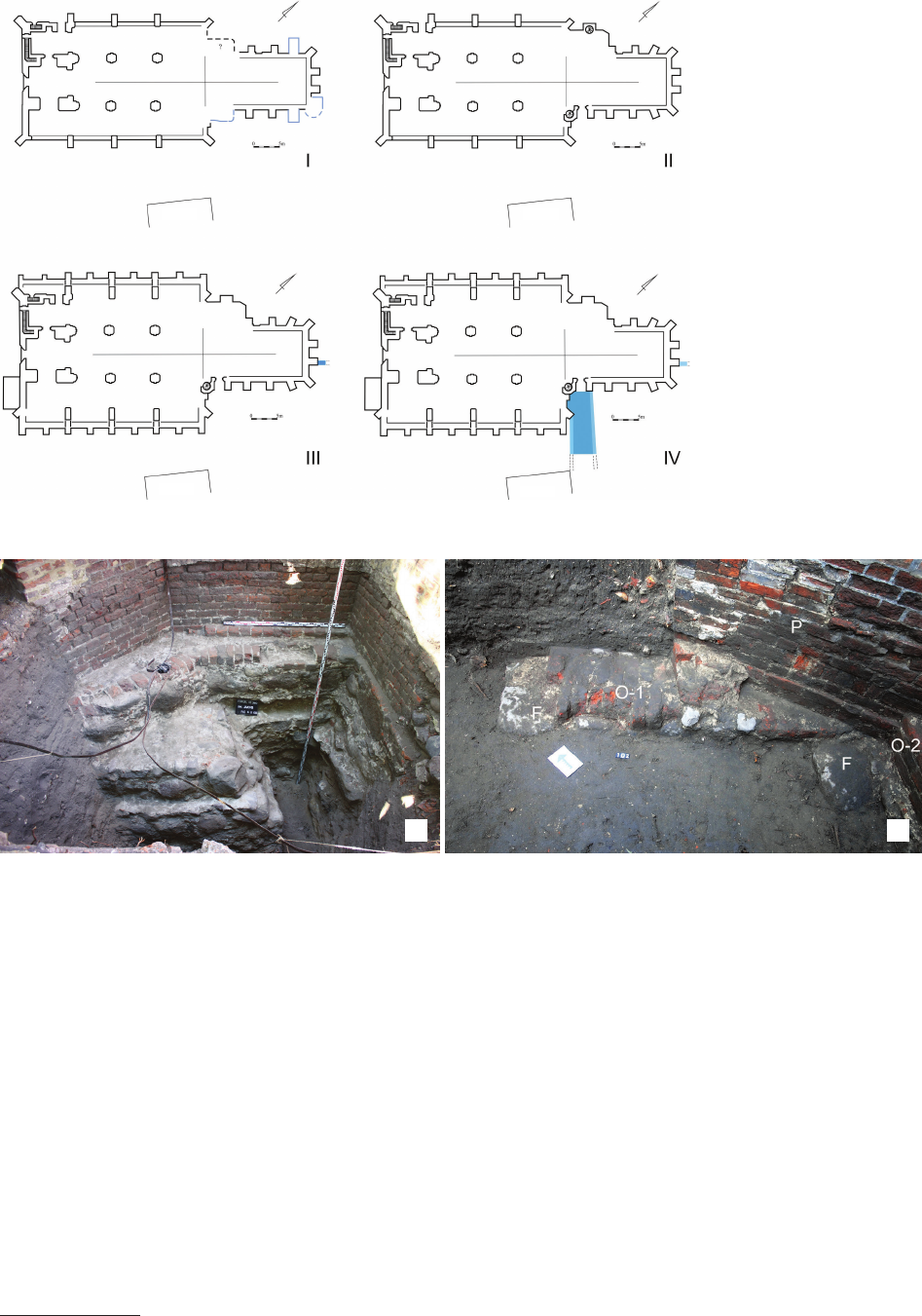

Of the many publications, two are particularly important

for the archaeologist studying architecture. The rst were

the research of Mroczko (1980), who demonstrated that St.

James’s Church was not a homogenous structure, but was

rather modied during its construction. Based on the “ab-

normal” arrangement of the corner, doubled buttresses of

the chancel, she suggested that the original concept of the

church had already been altered during construction

(Fig. 2B, 3A). She assumed that the chancel was extended

by a single bay, added from the east, over which a pseudo-

polygonal vault was installed. Due to the homogeneity of

the chancel with brick facing (a Polish bond), Mroczko be-

lieved that the hypothesis of the chancel’s extension could

only be veried in the foundation section. In conclusion,

she assumeded that the construction of the chancel began

in the 4

th

quarter of the 13

th

century, and subsequent con-

struction phases lasted from 1309 to approximately 1349

(Mroczko 1980, 167, 168). The second researcher, Frey-

muth (1981)

11

, was also doubteful that the year 1309 could

be the starting point of construction work on the church

and rightly believed that this date could be connected with

the reconstruction of the chancel. He suggested also, that

the entire structure was built by at least two masters and

that older forms are found in the naves, so the chancel is

younger than the naves (!). He stated that the master of

1309 must have taken into account remnants of an older

building, which may have had a polygonally closed chan-

cel, converted to a square one after 1309. According to

Freymuth, the new chancel was built on old foundations

the length and width of the old choir (1981, 14, 28, 30,

56–66, 72, 73); ultimately, he concluded that by the begin-

ning of the 14

th

century, nothing remained of the original

chancel, but the naves had survived in their original form.

He believed that around 1253 (before the city foundation)

the construction of the rst church with a three-sided clo-

sure began, from 1309 a new chancel was built, and al-

ready in 1349 the construction of the rst of the side cha-

pels between the buttresses of the naves began (Freymuth

1981, 83, 98) (Fig. 2B).

Liliana Krantz-Domasłowska expressed the opposite

opinion, claiming that […] thepresbyteryhadthesame

formasithastodayfromtheverybeginning (Krantz-Do -

ma słow ska, Domasłowski 2001, 47). Jakub Adamski was

convinced of the perfect compositional uniformity of all the

presbytery elements (2010, 19), and Adam Soćko conclud-

ed that the dierent arrangement of the diagonal buttresses

11

Freymuth was associated with Toruń until the end of World War II.

He died in Goslar in 1953. Only a year after Mroczko’s publication did

his work on the stages of construction of St. James’s Church appear.

What is signicant here is that many of the conclusions reached by both

researchers, undoubtedly formed independently, are convergent, and that

several of them have been positively veried.