68 Barbara Świt-Jankowska

attractiveness of the museum. It should be noted at this

point that usually the elements of an exhibition are digi-

tized: individual artifacts, documents, etc. – less frequently

the places where they are exhibited. An intermediate ver-

sion can be created by the so-called virtual tour, based on

the technology of combining 360-degree panoramas – an

example of such a solution is, among others, the Louvre

(Musée du Louvre “Virtual tour”), the Vatican Museum

(Musei Vaticani “Virtual tours”), but a similar possibility is

also provided by the National Museum in Poznań, branch

in Śmiełów (National Museum in Poznań, Śmiełów “Vir-

tual tour”). The above solution allows to get acquainted

with the structure of the building only to a limited extent

– depending on the number of photos and the intentions of

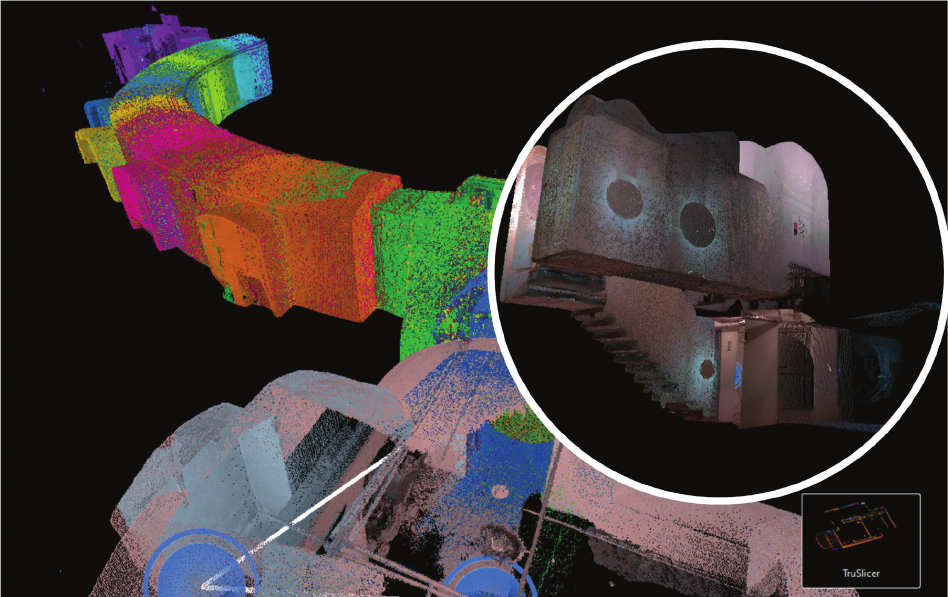

the creator. Making a full digital model (point cloud, pho-

togrammetry, etc.) is denitely more labour – and cost-in-

tensive, but its advantage is full freedom in exploring the

object. This type of work is usually performed for a histor-

ic building, often requiring virtual reconstruction (Götz

et al. 2023). In the case of museum objects, we usually deal

with buildings in relatively good technical condition, but

the possibility of combining a digital model with gaming

software opens up entirely new possibilities of exploration

(Campanaro, Landeschi 2022). The combination of a digi-

tal model (in this case a Roman villa) with eye-tracking

technology (VR) allowed to record the body position, head

and eyeballs movements of virtual “guests” which can be

useful in a museum facility, for example, when planning

a new exhibition. Considering that 3D scanning technolo-

gies, photogrammetry and LIDAR are becoming more and

more common and available, it can be expected that the use

of digital twin for this type of application will increase. In

view of the above, WA PP started cooperation with the Na-

tional Museum in Poznań, aimed at creating a digital model

of the Adam Mickiewicz Museum in Śmiełów (a branch of

the National Museum in Poznań) and exploring the possi-

bilities and potential of various inventory methods, as well

as determining their potential for planning further expan-

sion of the museum and the virtual tour path.

Adam Mickiewicz Museum, Palace in Śmiełów

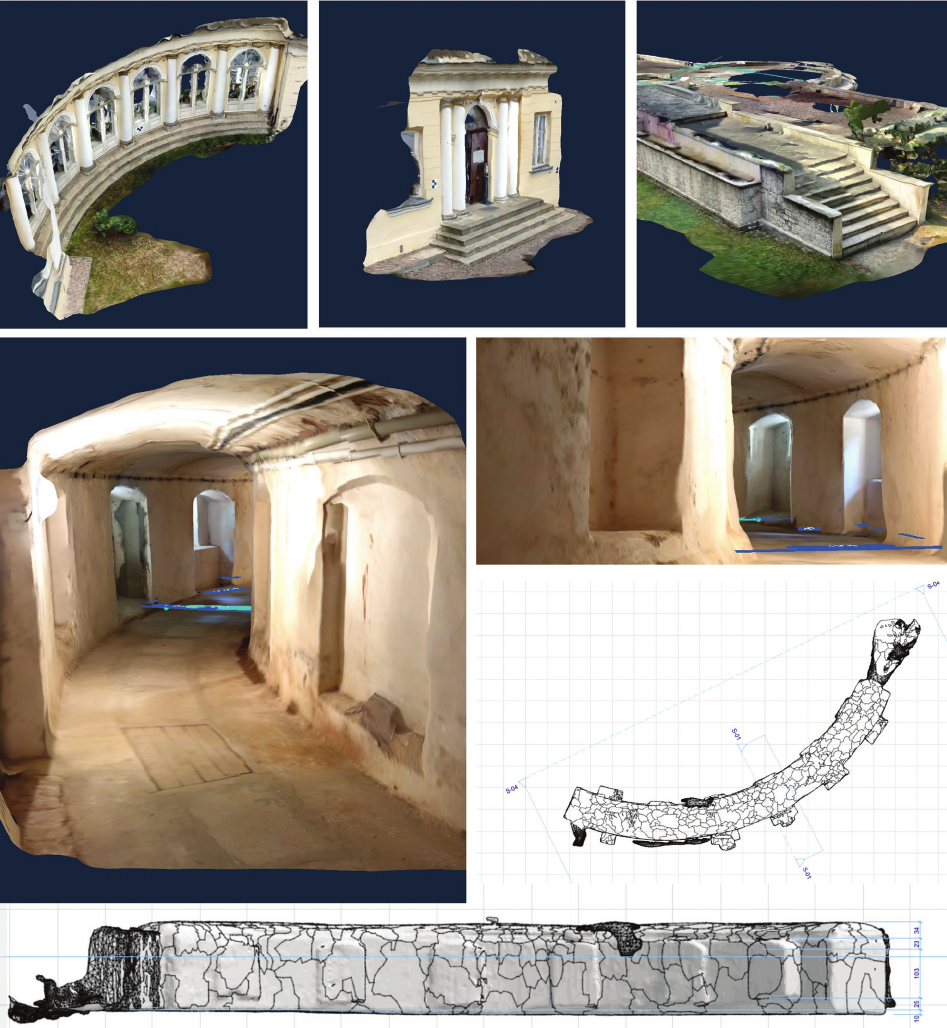

The palace in Śmiełów was built around 1797 on the

order of Andrzej Gorzeński, regent of Poznań municipal

government. He commissioned the construction to a well-

known Warsaw architect, Stanisław Zawadzki, who cre-

ated a classicist palace with two quarter-circular galleries

connected to the side in the Palladian style – a motif char-

acteristic of the residential architecture of Greater Poland

(Wielkopolska region) at that time (Fig. 1). The residence

in Śmiełów, surrounded by a picturesque landscape park,

forms a viewing axis with the complex of the classicist

church in Brzóstków. The stucco work in the palace inte-

riors was done by Michał Ceptowski, and the wall paint-

ings by two brothers: Antoni and Franciszek Smuglewicz.

Despite visible stylistic references to other realizations of

this type, e.g., in Racot or Sierniki, the palace in Śmiełów

is distinguished by original solutions in the decoration of

the façade of the main body of the palace, as well as in

the interior design – the lack of connection of the living

aspects of philosophical nature and conceptual foresight

(Leshchenko 2020). An increasing number of institutions

are establishing departments responsible for digital asset

management, and the rapid development of this eld is be-

ing discussed at conferences and in scientic publications,

covering a wide range of activities: from multimedia ele-

ments complementing traditional exhibitions, to mobile

tours and virtual exhibitions on websites, as well as meth-

ods of collecting information on collections and their dis-

semination (tablets, 3D prints, digital narratives). More

and more often, articial intelligence algorithms are being

used to present the collections, allowing for an increasing-

ly individualized visitor’s program, as well as augmented

reality, mobile applications, and social media interactions.

It allows for the creation of a platform on which a dialogue

between the museum and its guests is possible. In addition,

the sense of belonging and the ability to participate in dig-

ital narratives, interact with original artifacts in augmented

reality or communicate via mobile devices and digital plat-

forms creates a new dimension of the museum – a parallel

world in which digital twin technology, applied to its

premises, can be particularly helpful, especially if we are

dealing with a historic monument. In 2015, Danuta Fol-

ga-Januszewska wrote: The nature of the collections does

notdeterminepopularityandisnotafactorinuencingthe

interest of recipients. The way of interpreting the collec-

tions, creating an appropriate narrative, is of fundamental

importance (Folga-Januszewska 2015, 135). It shows the

importance of the way of presenting collections and the

ability to hit the users’ needs with the message

3

. In this

context, the museum becomes a setting for individual ex-

perience of visitors, who, supported by technology, can

customize the experience to their individual needs – and

the place where it happens begins to play a signicant

role

4

. The trend can be observed primarily during the cre-

ation of new facilities, in which the space closely interacts

with the exhibition and becomes its part, increasing its at-

tractiveness (e.g. the Warsaw Uprising Museum, the Mu-

seum of the Second World War in Gdańsk or the Silesian

Museum in Katowice). However, this approach is inher-

ently almost impossible if we are dealing with an existing

building – often a monument per se. In such a situation, the

possibility of creating a parallel, virtual model of the mu-

seum can, on the one hand, allow to change the way of

display in augmented reality, and, on the other hand, can

help to nd an optimal solution that does not negatively

aect the historic fabric of the building and harmonizes

with the needs of artifacts. Combining the needs of both

approaches allows for greater integration of the collections

with the place where they are presented and enhances the

3

An excellent example of this approach is the series on the history

of the servant Stefcia, carried out by the Zamoyski Museum on their so-

cial media. The series was created to bring the realities of servant life in

the 19

th

and 20

th

centuries closer. Joanna Adamek is responsible for the

script and direction; the actors are: Aneta Ćmiek and Michał Rudnicki

(Muzeum Zamoyskich “A series of short lms…”).

4

An example of this approach is the Groninger Museum in the

Netherlands – created by Frans Haks and Alessandro and Francesco

Mendini, opened in 1986.