$UHDVVHVVPHQWDQGHPRWLRQVFRQQHFWHGZLWKDEXLOGLQJFRQGLWLRQHGE\LWVH[WHUQDODSSHDUDQFH" 85

Contemporary cognitive psychologists tend to agree

that perception is not merely a sum (or a simple com-

bination) of sensory impressions. Human observations

do not exclusively result from physical external stimu-

lation, i.e. observations such as Dom Handlowy ‘Sol-

SRO¶LQ:URFáDZµ*DOHULD&HQWUXP¶VKRSSLQJDUFDGHV

%DVLOLFD µ/LFKHĔ¶ DUH QRW RQO\ OLWHUDO WHFKQLFDO UHÀHF-

tions of physical properties of these objects. Perception

involves individually built cognitive representations –

mental equivalents of real objects. It is full of additional

information which is not directly observed in the stimuli,

IRUH[DPSOHLQDEXLOGLQJ:KDWVRUWRILQIRUPDWLRQH[-

DFWO\":HGRQ¶WNQRZWKLVLVZKDWZHDUHWU\LQJWRJHW

to know from people and it is one of the most important

FKDOOHQJHV IRU SV\FKRORJ\ WRGD\ :KDW ZH GR NQRZ LV

that each object in each of our minds is something more

than an image produced by our brain through light waves

comparable, for instance, with a photograph.

Certainly, the perceived reality has relatively objective

properties but from the viewpoint of a psychologist, ZKDW

a particular man perceives LV PRUH VLJQL¿FDQW WKDQ DQ\-

thing else. The mental representation, i.e. an individually

FRQVWUXFWHG DQG UHÀHFWHG IUDJPHQW RI WKH REMHFWLYH UHDO-

ity, is one of the key notions in cognitive psychology [16,

p. 27]. Everybody ‘carries’ in their minds their own and

unique representation of the world but every man still cre-

ates new representations of various situations in which he

LVDQGREMHFWVWKDWKHREVHUYHV:HFDQVHHWKDWWKHPLQG

consists of ‘numerous and mutually connected cognitive

UHSUHVHQWDWLRQV¶>S@:HPDQLSXODWHWKHVHUHSUHVHQ-

tations so that the perceived world makes sense and it can

effectively function. The surrounding objects – sources of

stimuli, for example architectural ones, emanate the energy

of optical waves. Each man transforms this energy in an

LQGLYLGXDOZD\, the energy that carries some objective in-

formation for sensory receptors (wavelength, etc.). In this

way, perception is created, namely: an individual, unique

representation of reality, for example, architectural one.

This is a relatively well documented hypothesis in psychol-

ogy concerning the cognitive functioning of man [16].

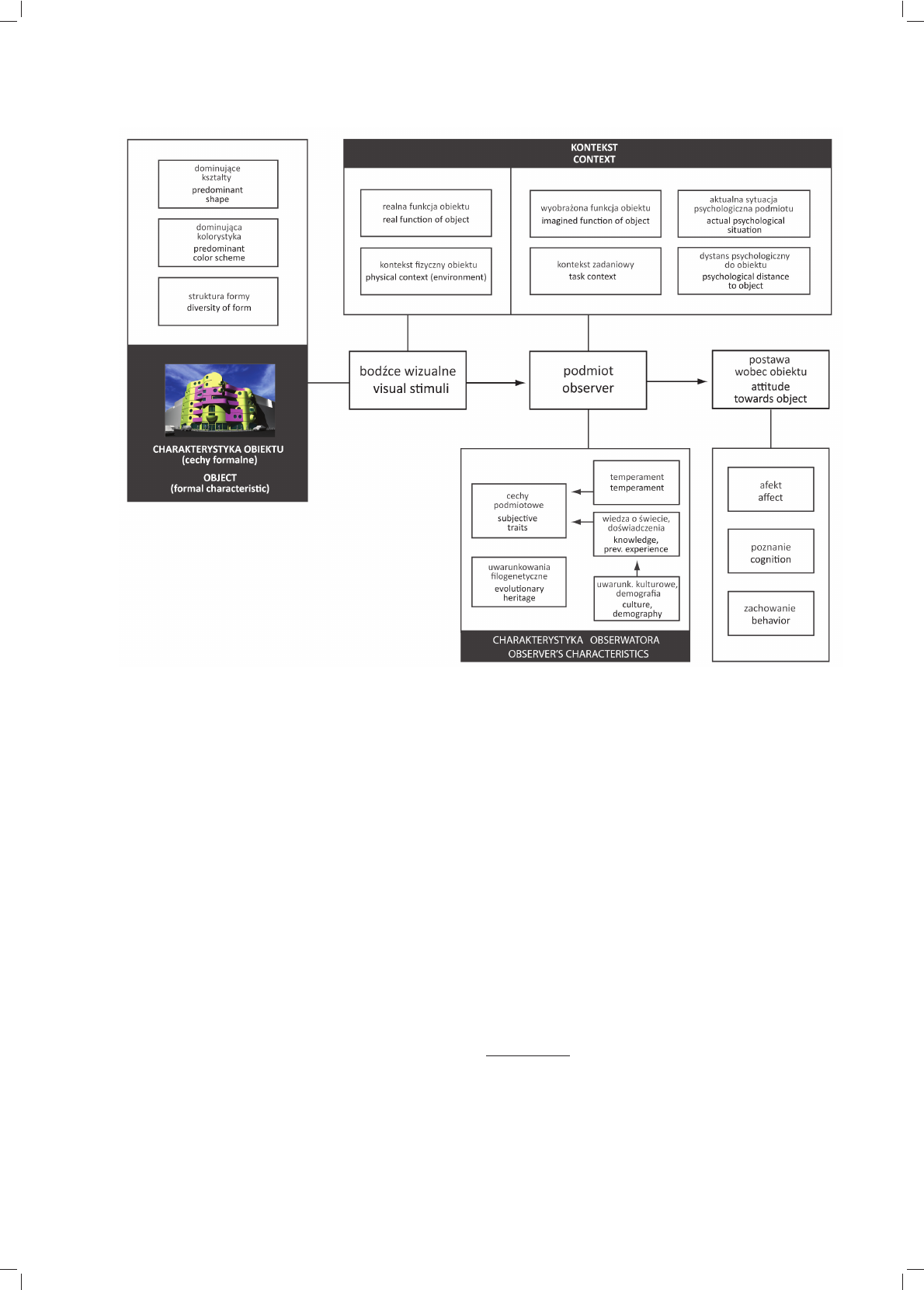

Thus, perception is most probably a creative process

which requires a certain kind of activity from man. It is

conditioned by a kind of a stimuli and its objective prop-

erties, physical context in which the observer found the

stimuli, subjective properties of the observer, culture and

many other factors which shall be discussed later along

ZLWK WKH GLVFXVVLRQ RI DWWLWXGHV ,W LV UHDOO\ GLI¿FXOW WR

describe this process itself – what it looks like and what

its physical course is – it takes place in the mind though.

However, we can observe the effects of the perception

process, which can be the observer’s declarations con-

cerning an object, the observer’s attitude to an object or

actually observed behaviours connected with an object

HJDSSURDFKLQJZDONLQJDZD\SXUFKDVHRIDÀDWDU-

chitectural design acceptance, etc.).

Measurement of attitudes which are observable and

enable us to make a direct comparison of perception

effects is often used in such diagnoses which examine

man’s relations with the environment. In environmental

psychology, research on attitudes, for instance, towards

various sceneries or objects is often aimed at examining

‘satisfaction with a particular place’ which is always dif-

ferent or simply: evaluation of a particular environment

[3], [4], [21].

:KDWLVWKHHVVHQFHRIDWWLWXGHVWRZDUGVDUFKLWHFWXUDOREMHFWV"

An attitude, i.e. the information we try to get from the

subjects is always ‘somebody’s’ [20, pp. 180–181] and

FDQEHGH¿QHGDVDSHUPDQHQWDVVHVVPHQW±SRVLWLYHRU

QHJDWLYH ± RI SHRSOH REMHFWV DQG LGHDV […] $WWLWXGHV

FRQVWLWXWHDQDVVHVVPHQWZKLFKPHDQVWKDWWKH\DUHSRVL-

tive or negative reactions to something [...] [1, p. 313].

A certain kind of emanation of individual (differenti-

ated) attitudes towards objects can be, for example, vari-

ous persons’ comments on a certain building. Krystian

%LHVLHNLHUVNL DQ DUFKLWHFW ZKR LV FULWLFDO RI :URFáDZ

Dom Handlowy ‘Solpol’ (shopping mall) and actively

opts for its demolition, says: [Solpol] 7KLV LV D JOLWWHU

7KH GHVLJQHU ZDV FHUWDLQO\ IDVFLQDWHG E\ WKH VSLULW RI

the époque but he forgot that architecture is supposed to

serve generations for centuries>@ZKHUHDV.DWDU]\QD

+DZU\ODN%HUH]RZVNDDFLW\UHVWRUHUVD\V,DGPLWWKDW

,DPQRWSOHDVHGZLWKWKHLGHDRIGHPROLVKLQJµ6ROSRO¶

, WKLQN WKDW WKH EXLOGLQJ LV D V\PERO RI LWV pSRTXH [6].

3LRWU)RNF]\ĔVNL:URFáDZFLW\DUFKLWHFWDQGDµ6ROSRO¶

defender refers to the building as follows: 7KLVLVWKH¿UVW

WLPHWKDWLQ:URFáDZLQWKHFKXUFKQHLJKERXUKRRGDQGLQ

the strong historical context a building has been erected

ZKLFKJHWVRXWRIOLQH [12] and This is one of the brav-

HVW DQG PRVW LQWHUHVWLQJ GHVLJQV LQ DIWHUZDU :URFáDZ

,W VKRZV WKDW ZH DUH QRW DIUDLG RI QHZ VROXWLRQV [19].

=ELJQLHZ 0DüNyZ DQ DUFKLWHFW IURP :URFáDZ ZKR

DOVRRSSRVHVWKHGHPROLWLRQRI6ROSROVDLGIRU³*D]HWD

:URFáDZVND´,ILWGHSHQGHGRQPH,ZRXOGUDWKHUWU\WR

UHQRYDWHWKHEXLOGLQJ6ROSROLVDQLQWHUHVWLQJH[DPSOHRI

post-modernism [19].

0DáJRU]DWD 2PLODQRZVND DQ DUW KLVWRULDQ ZKLOH

GLVFXVVLQJ DQRWKHU REMHFW ± %DVLOLFD LQ /LFKHĔ ± VD\V

+RWHOVDQGH[FOXVLYHUHVLGHQFHVOLQHGZLWKPDUEOHJOLW-

WHULQJZLWKJROGDQGFU\VWDOFKDQGHOLHUVOLNHIURPµ'DO-

ODV¶RUµ'HQYHU¶¿OPVHULHVPDNH/LFKHĔD&DWKROLF/DV

9HJDV DOWKRXJKLW FDQ DOVREH DVVRFLDWHG ZLWKWKH 5R-

PDQLDQVRFLDOLVWUHDOLVPDUFKLWHFWXUHRIODWH&HDXúHVFX

>S@DQGVKHGH¿QHVWKHZKROHWKLQJDVRQHRI>@

WKHPRVWLQFUHGLEOHZRUNVRIPHJDNLWVFKLQ(XURSH [13,

p. 39].

Attitudes may refer not only to buildings, but also to

objects of street furniture or widely understood organi-

sation of space (e.g. public space). For instance, a dis-

cussion about the city dwarfs which in fact are already

DWRXULVWODQGPDUNRI:URFáDZKDVEHHQUHFHQWO\LQLWLDWHG

,Q³*D]HWD:\ERUF]D´SURIHVVRU.ODXV%DFKPDQQZURWH