36 Wojciech Niebrzydowski

ed by their large scale, sculptural form and raw concrete

texture. Researcher Atilla Yücel points to the inuence of

many dierent architects on other buildings [27, p. 140],

which contributed ultimately to the heterogeneous archi-

tecture of the METU Campus.

Conclusions

Brutalism made its way from the West to Islamic coun-

tries at the same time as it did to other parts of the world.

It was brought to this region by the Western masters – Le

Corbusier, Louis I. Kahn, and Minoru Yamasaki. However,

it should be emphasized that brutalist architecture was

developed and transformed in Islamic countries by local

architects. Some of them rst collaborated with foreign

architects. An example was Mohammad Reza Moghtad-

er who worked with Minoru Yamasaki. Native architects

used solutions characteristic of the brutalist trend, but

also introduced their individual concepts and elements.

They often drew inspiration from vernacular architecture.

Therefore, a very interesting feature of brutalist architec-

ture in Islamic countries is its duality. On the one hand, it

is characterized by consistency – specic aesthetic eects,

most commonly used materials, or repetition of certain

solutions and formal elements. On the other hand, many

dierent tendencies developed in it, caused not only by

the individuality of the architects but also by the referenc-

es to local conditions. Among the most important archi-

tects of this trend are Abdeslem Faraoui, Kamran Diba,

Houshang Seyhoun, Muzharul Islam, Günay Çilingiroğlu,

Muhlis Tunca, Behruz and Altuğ Çinici.

Buildings with various functions, especially prestigious

buildings, were erected in a brutalist style in Islamic coun-

tries. However, compared to other parts of the world, there

are few religious buildings. There are not many multi-fam-

ily buildings and housing estates either. It should be noted

that earlier buildings erected in Islamic countries generally

had simpler forms. However, the forms of buildings con-

structed in the last phase of brutalism were very expressive

and dramatized.

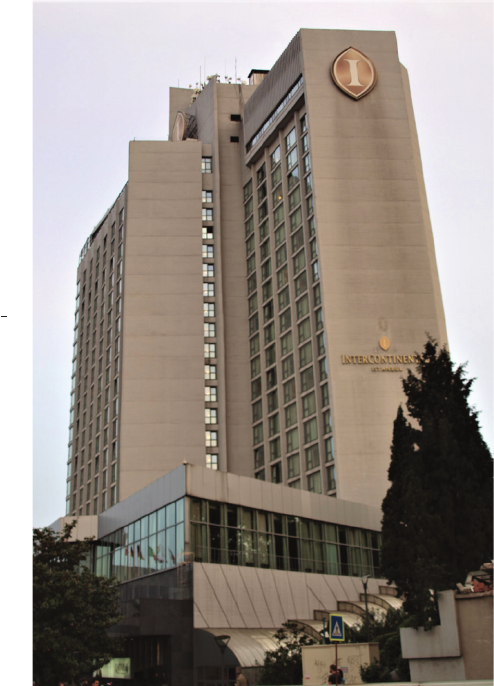

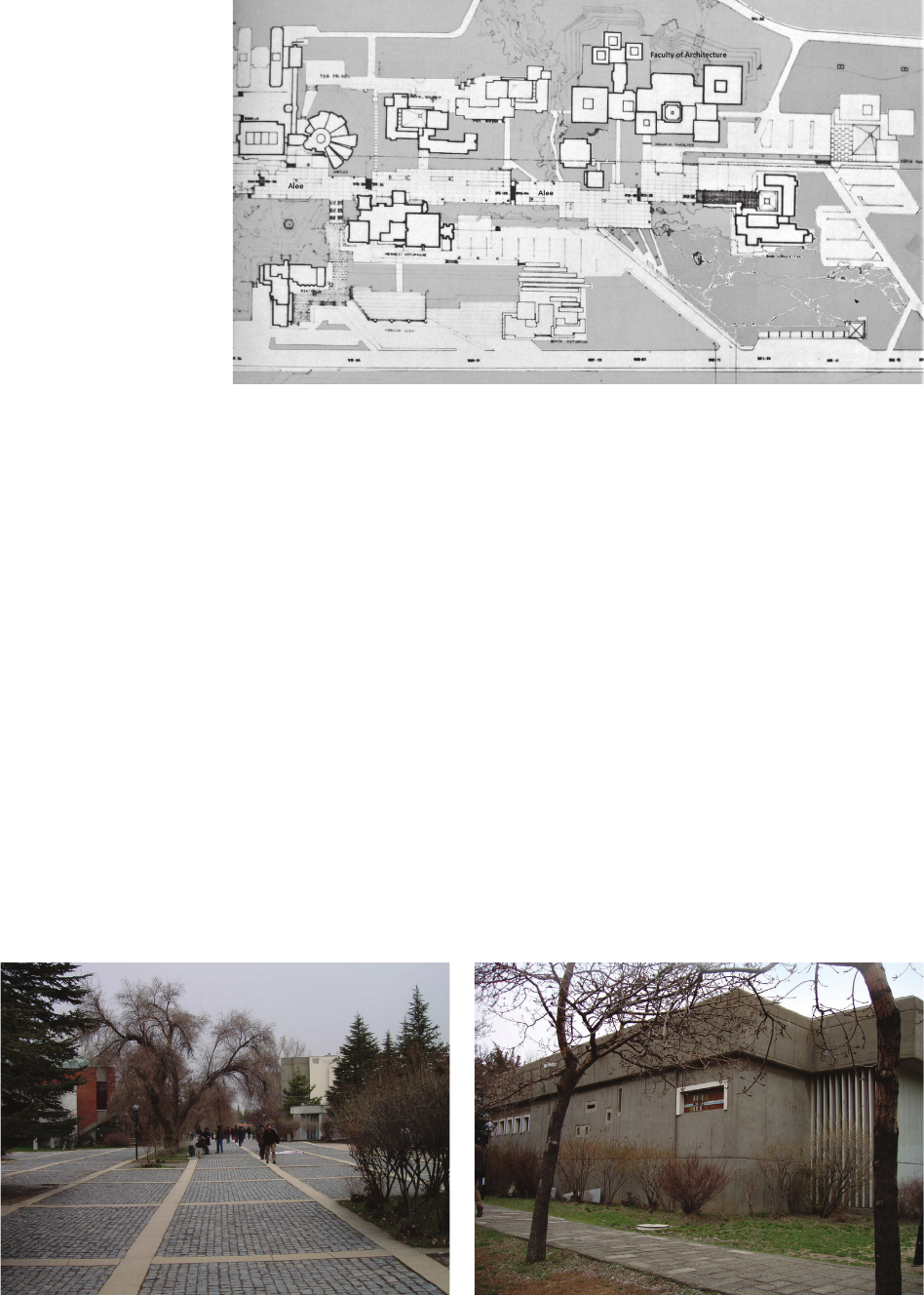

One of the most signicant works of brutalism in Islam-

ic countries is the METU Campus in Ankara. 60 years

since its foundation, the campus is a group of stylistical-

ly diverse buildings. However, it remains a unique com-

plex with the largest number of brutalist buildings erected

in one place in Turkey. In this respect, the campus also

stands out in comparison with all other Islamic countries.

Although it was built rst, the Faculty of Architecture

Building presents the highest architectural value among

the METU buildings. The design ideas of architects Altuğ

and Behruz Çinici were very avant-garde at that time and,

fortunately, were consistently implemented.

The form and spatial arrangement of the METU Facul-

ty of Architecture Building reect the most important fea-

tures and elements of the brutalist trend: massiveness and

heaviness, sincerity of materials, articulation of solids and

elements forming a building, exposing internal functions

in an architectural form, emphasizing the importance of

movement and elements of pedestrian circulation, domi-

nance of concrete. There are also individual solutions in

the building, usually less common in brutalist architec-

ture. The building has a calm, balanced formal expression,

while other works of this trend were often very strong and

dominant. The building continues its perpendicular geom-

etry without any oblique elements or curvatures. There are

no cantilevers or service towers in the form. The Çinicis

drew on the vernacular architecture of Anatolia, some-

times in a very direct way. It should be emphasized that

the building is one of the few in the world where the inu-

ence of the New Brutalism is clearly visible. The Çinicis

undoubtedly shared the ideas propagated by the Smith-

sons, including As Found, objectivity to reality, and apo-

theosis of ordinariness.

Translated by

Wojciech Niebrzydowski

References

[1] Banham R., The New Brutalism, “The Architectural Review” 1955,

No. 12, 354–361.

[2] Banham R., The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic?, Reinhold Pub-

lishing Corporation, New York 1966.

[3] Smithson A., Smithson P., House in Soho, London, “Architectural

Design” 1955, No. 12, 342.

[4] Boesiger W., Le Corbusier, Le Corbusier: Oeuvre Complete 1952–

1957, Vol. 6, Les Editions D’architecture, Zürich 1966.

[5] Boesiger W., Le Corbusier, Le Corbusier: Oeuvre Complete 1957–

1965, Vol. 7, Les Editions D’architecture, Zürich 1966.

[6] Atlas of Brutalist Architecture, V. McLeod (ed.), Phaidon, New York

2018.

[7] SOS Brutalism: A Global Survey, O. Elser, Ph. Kurz, P. Cachola

Schmal (eds.), Park Books, Zürich 2017.

[8] Bozdoğan S., Akcan E., Turkey: Modern Architectures in History,

Reaktion Books, London 2012.

[9] Hassanpour N., Soltanzadeh H., Tradition and Modernity in Con-

temporary Architecture of Turkey (Comparative Study Referring to

Traditional and International Architecture in 1940–1980), “The

Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication” 2016,

Vol. 6, 1167–1183, doi: 10.7456/1060AGSE/002.

[10] Vidler A., Troubles in Theory V: The Brutalist Moment(s), “The

Architectural Review” 2014, No. 235, 96–102.

[11] Iranian Architecture and Monuments: Houshang Seyhoun, http://

www.iranchamber.com/architecture/hseyhoun/houshang_seyhoun.

php [accessed: 13.11.2021].

[12] Henri Tastemain 1922–2012 / Eliane Castelnau 1923–, https://mam-

magroup.org/henri-tastemain-eliane-castelnau [accessed: 27.10.2021].

Acknowledgements

The research was carried out as part of work WZ/WA-IA/4/2020 at the

Białystok University of Technology and nanced from a research subsidy

provided by the Ministry of Education and Science.