Ogrody cysterskie – mit a rzeczywistość /Cistercian gardens – myth and reality 61

Streszczenie

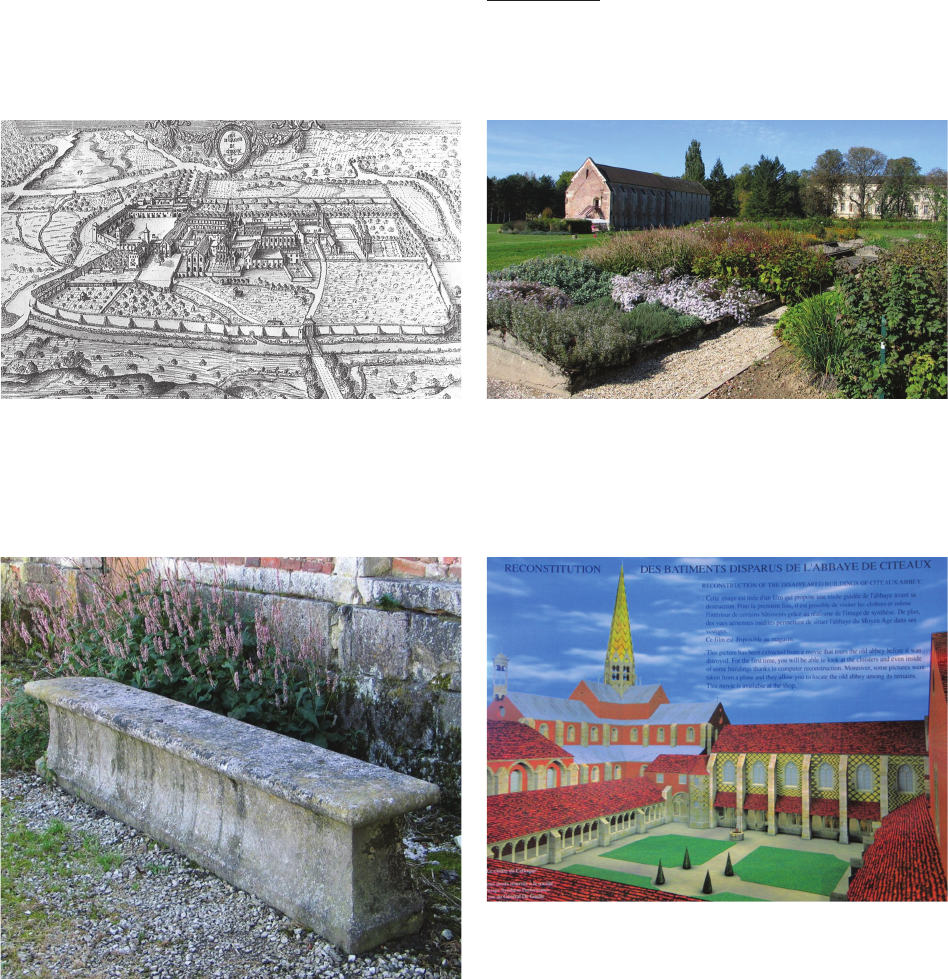

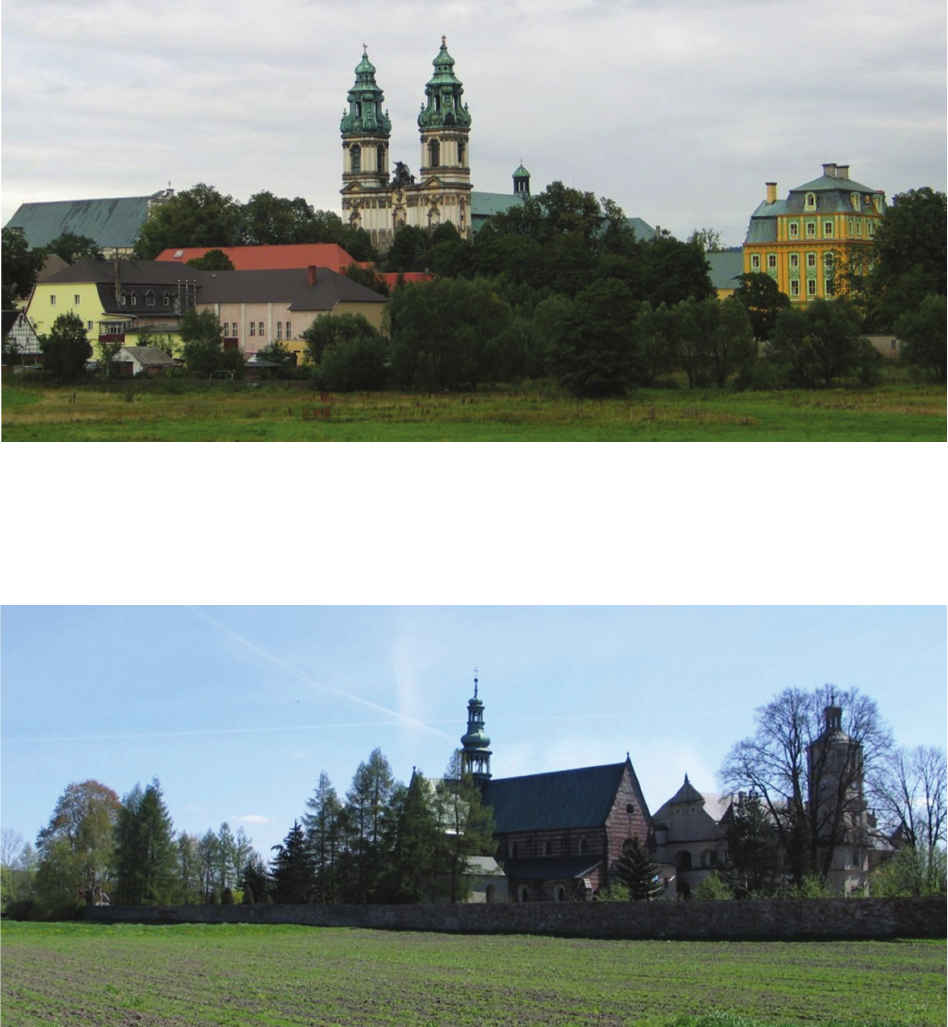

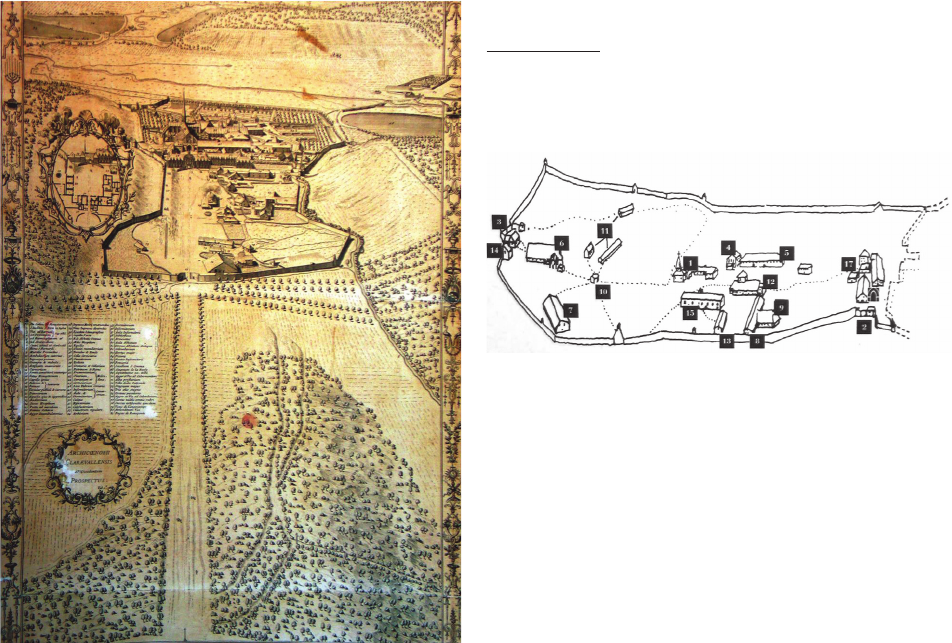

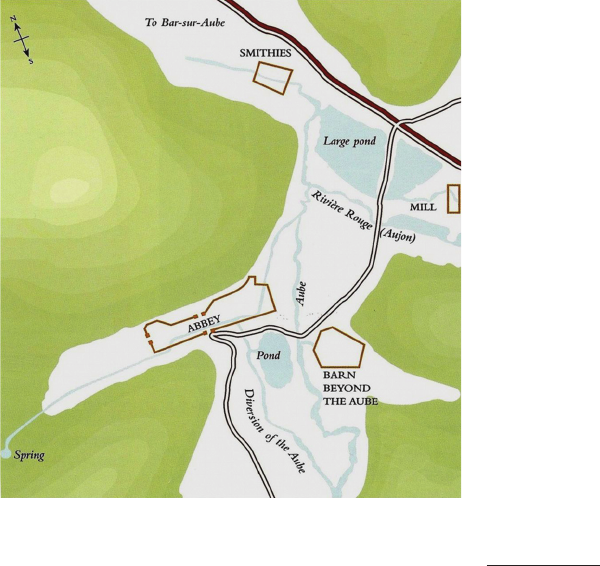

Program użytkowy cysterskiego klasztoru jest swoistym, przestrzennym wyrazem reguły zakonu. Biali, czy też jak nazywano ich szarzy mnisi,

realizowali go, wybierając na budowę swego opactwa miejsce nad rzeką, w otoczeniu lasów i mokradeł, ale o korzystnych warunkach środowisko-

wych i potencjalnych możliwościach rozwoju gospodarczego. W sposób konsekwentny wkomponowywali w nie swoją zabudowę, którą z czasem

w miarę potrzeb rozbudowywali, a otaczające ją środowisko przekształcali. Istotnym elementem cysterskiego zespołu zabudowy klasztornej były

dopełniające ją programowo, a pod względem przestrzennym przenikające struktury budowlane – ogrody. Struktura przestrzeni ogrodowych

była wynikiem realizacji reguły i choć funkcje podstawowych typów ogrodów aż do czasów kasat utrzymały się, to ich kompozycje, jak też i lokali-

zacje w obrębie zespołów klasztornych ulegały zmianom, co ściśle wiązało się z wykorzystaniem przestrzeni całego zespołu i poszczegól nych

obiektów budowlanych, a te niekiedy zmieniały swoje funkcje i formy. W niniejszym artykule przestawiono podstawowe zasady kompozycji

ogrodowych, prezentując pokrótce typy ogrodów, jakie istniały w klasztorach cysterskich. Odniesiono się tak

że do obowiązującej nadal literatury

dotyczącej średniowiecznego dziedzictwa ogrodowego w cysterskich klasztorach i poruszono problem ochrony autentyku związanego z działalnością

stricte cysterską. Nie można zapominać, że ewolucja opisywanych zespołów trwa, a istniejące domy klasztorne cystersów i innych zgromadzeń

w miarę swoich potrzeb tworzą na bazie dawnych zespołów ogrody współczesne, które to często nie mają wiele wspólnego z dawnymi kompozy-

cjami. Dziś przeważnie są to po prostu tereny wypoczynku, nierzadko z wkomponowanymi w układy zieleni obiektami sportu i rekreacji, ale także

elementami dekoracyjnymi całkowicie obcymi cysterskiej tradycji. Niezwykle ważne jest, aby przy całej atrakcyjności tych „nowości” założenia

klasztorne, w których obrębie istnieją relikty ogrodów, przenosiły do przyszłości dawną tradycję ogrodu klasztornego, który co prawda pod względem

funkcjonalno-kompozycyjnym wciąż ewoluował, ale przez wieki był ważnym nośnikiem treści symbolicznych i przekazu religijnego, a ponadto

istotnym dokumentem poziomu życia, wiedzy, a przede wszystkim stosunku człowieka do przyrody.

Słowa kluczowe: opactwo, cystersi, ogrody klasztorne, krajobraz

Abstract

A usable plan of the Cistercian monastery constitutes a specific spatial expression of the Rule of the Order. The White or the so called grey monks

carried out this plan by choosing a place to build their abbeys by a river, surrounded by forests and wetlands, but characterised by good environmen-

tal conditions and potential possibilities of economic development. They consequently built their development into nature, which they extended

as necessary and thus transformed the surrounding environment. A significant element of a Cistercian monastery development complex was consti-

tuted by gardens – building structures that complemented the development as regards its program and simultaneously permeated its space. The

structure of garden spaces was an effect of implementing the Rule and although functions of the basic types of gardens were maintained until the times

of dissolution of orders, their arrangements and locations within the monastery complexes underwent changes which was strictly connected with the

usage of the entire complex space and its particular buildings and these, in turn, at times changed their functions and forms. This article was aimed at

presenting the basic principles of garden arrangements and specifying briefly types of gardens that existed in Cistercian monasteries. It also included

references to the still vital literature of the mediaeval garden heritage of Cistercian monasteries and a discussion of the problem of protecting

the original connected with strictly Cistercian activities. We must bear in mind the fact that the evolution of the discussed complexes takes places

all the time and the existing Cistercian and other orders monastery houses create modern gardens on the base of the former complexes, in accordance

with their present needs, which frequently have little in common with the old arrangements. Today these places are quite often simply relaxation areas

with numerous sport and recreation facilities built into green arrangements and other decorative components that are totally alien to the Cistercian

tradition. With all the attractiveness of these ‘novelties’, it is extremely important that the monastery complexes within which the garden relics

are preserved could transfer into the future the old traditions of the monastery garden that underwent a constant evolution as regards its functions

and arrangement, but nonetheless throughout centuries was an important medium of symbolic content and religious aspects of life and moreover

it constituted a significant record documenting the level of life, knowledge and first of all an attitude of man towards nature.

Key words: abbey, Cistercians, monastery gardens, landscape

[9] Augustyniak J., Rozwój przestrzenny cysterskiego założenia klasz-

tornego w Sulejowie do końca XVI wieku w świetle badań archeo-

logicznych, [w:] A.M. Wyrwa, J. Dobosz (red.), Cystersi w spo łe-

czeństwie Europy Środkowej, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, Poznań

2000, 436–464.

[10] Augustyniak J., Cysterskie opactwo w Sulejowie. Rozwój przes-

trzen ny do końca XVI wieku w świetle badań archeologiczno-archi-

tektonicznych w latach 1989–2003, Muzeum Archeologiczne

i Et no graficzne w Łodzi, Łódź 2005.

[11] Kajzer L., Kogo deptali Cystersi w Rudach koło Raciborza?, [w:]

J. Olczak (red.), Archaeologia Historica Polona, t. 5, Wydawnictwo

UMK, Toruń 1997, 97–107.

[12] Piwek A.,

Architektura kościoła pocysterskiego w Oliwie od XII

do XX wieku. Świątynia zakonna białych mnichów, Wydawnictwo

Bernardinum, Pelplin 2006.

[13] Świechowski Z., Opactwo cysterskie w Sulejowie, PWN, Poznań 1954.

[14] Wyrwa A.M., Strzelczyk J., Kaczmarek K. (red.), Monasticon Cis ter-

ciense Poloniae, Dzieje i kultura męskich klasztorów cys terskich na

ziemiach polskich i dawnej Rzeczypospolitej od śred nio wiecza do cza-

sów współczesnych, t. 1 i 2, Wydawnictwo Poznańs kie, Poznań 1999.

[15] Milecka M., Ogrody cystersów w krajobrazie małopolskich opactw

filii Morimondu, Wydawnictwo KUL, Lublin 2009.

[16] Milecka M., Średniowieczne dziedzictwo sztuki ogrodowej klasz-

torów europejskich, „Hereditas Monasteriorum” 2012, vol. 1, 31–56.

[17] Opsomer-Halleux C., The medieval garden and Its Role in Medi-

cine, [w:] E.B. Macdougall (red.), Medieval gardens, Dumbarton

Oaks Research Library and Collection Trustees for Harvard Uni-

versity, Washington 1986, 93–113.

[18] Milecka M., Zarządzanie wodą w opactwach cysterskich, [w:]

K. Gerlic (red.), Architektura i technika a zdrowie, Zakład Graficz-

ny Politechniki Śląskiej, Gliwice 2008, 143–154.

[19] Milecka M., Doliny cysterskie – historia i współczesność, [w:]

D. Chylińska, J. Łach (red.), Studia krajobrazowe a ginące krajobrazy,

Zakład Geografii Regionalnej i Turystyki, UWr, Wrocław 2010, 63–72.

[20] Stoffler H.D., Kräuter aus dem Klostergarten, Jan Thorbecke

Verlag, Stuttgart 2005.

[21] Kinder T.N., Cistercian Europe. Architecture of Contemplation,

Grand Rapids, Michigan/Cambridge 2002.

[22] Milecka M., Krajobraz opactwa sulejowskiego – historia prze-

kształceń, [w:] J. Janecki, Z. Borkowski (red.), Krajobraz i ogród

wiejski. Zmienność krajobrazów otwartych, t. 5, Wydawnictwo

KUL, Lublin 2008, 187–206.

[23] Kłoczowski J., Cystersi w Europie Środkowowschodniej wieków śred-

nich, [w:] A.M. Wyrwa, J. Dobosz (red.), Cystersi w społe czeństwie

Europy Środkowej, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, Poznań 2000, 27–53.

[24] Kłoczowski J., Dzieje chrześcijaństwa polskiego, Świat Książki,

Warszawa 2007.

[25] Machowski M., Architektura kluniacka i cysterska, [w:] J. Mrozek

i in. (red.), Sztuka świata, t. 4, Arkady, Warszawa 2004, 7–29.

[26] Haushild S., Das Paradies auf Erden. Die Gärten der Zisterzienser,

Thorbecke, Stuttgart 2007.

[27] Holeczko A., Dyskusja, [w:] E. Chojecka (red.), Sztuka a natura.

Materiały XXXVIII Sesji Naukowej Stowarzyszenia Historyków

Sztuki prowadzonej 23–25 listopada 1989 roku w Katowicach,

Oddział Górnośląski Stowarzyszenia Historyków Sztuki, Katowice

1991, 448–466.