84 Dominika Kuśnierz-Krupa, Kazimierz Kuśnierz, Małgorzata Hryniewicz, Julia Ivashko, Dorota Bober

the standpoint of changes to a town’s urban layout and

its historical monuments. The fth and nal stage of the

procedure utilizes synthesis to determine the state of pres-

ervation of a historical urban layout and the legibility of

the model based on which it had been delineated. For this

study, the procedure was enhanced with a sixth stage,

which analyzes the current state of statutory conservation

of the urban layouts under investigation [3].

Polish Renaissance towns were previously studied by,

among others, Wojciech Kalinowski [4], [5], Jerzy Ko wal-

czyk [6], Mieczysław Książek [7], [8], Kazimierz Kuś nierz

[9]–[12], Tadeusz Tołwiński [13], Tadeusz Wróbel [14],

Danuta Kłosek-Kozłowska [15], Teresa Zarębska [16], and

Dominika Kuśnierz-Krupa and Michał Krupa [17]. H

ow-

ever, these studies were mostly conned to the analysis

of the urban structure and architectural heritage of Re-

naissance towns and cities. The statutory conservation of

Renaissance urban layouts has thus far been explored only

marginally in academic studies.

Renaissance urban layouts in Poland

In Polish urban planning history, the Renaissance is con -

sidered to have coincided with the period between the

mid-16

th

and the 17

th

centuries [8, p. 7]. Many changes in

urban planning took place in this period. They were dic-

tated by, among others, an evolution of conducting war-

fare, which necessitated change in defensive systems, new

planning ideas (la città ideale), which came to Poland

from Western European countries, and the socio-politi-

cal situation in the country [13]. This caused Polish cities

planned during the Renaissance to be, in most cases, dif-

ferent from cities founded in the Middle Ages in terms of

urban construction.

It should be noted that Polish Renaissance urban lay-

outs can be divided into two essential groups: urban and

residential settlements and commercial settlements. Irre-

spective of this, it should be mentioned that, apart from

cities and towns that deliberately referenced “ideal” de-

signs by Italian theorists in their urban structure, fortress

cities were also built during this period, erected predom-

inantly by wealthy landowners in borderland territories,

in addition to spatial plans of so-called new cities that

formed annexes to already existing urban structures, such

as squares, streets, and engineering and sanitary construc-

tions [12, pp. 99–106, 17].

During the Renaissance, magnate families (e.g., the Lu -

bomirski, Krasicki, Zamoyski, Sieniawski, Czartoryski,

Jor dan, Sienieński and Cieszanowski families) had a sig-

nicant inuence on urbanization as, due to constantly

expanding their estates, they required local administrative

and commercial centers that mostly served as markets for

the products of their latifundia.

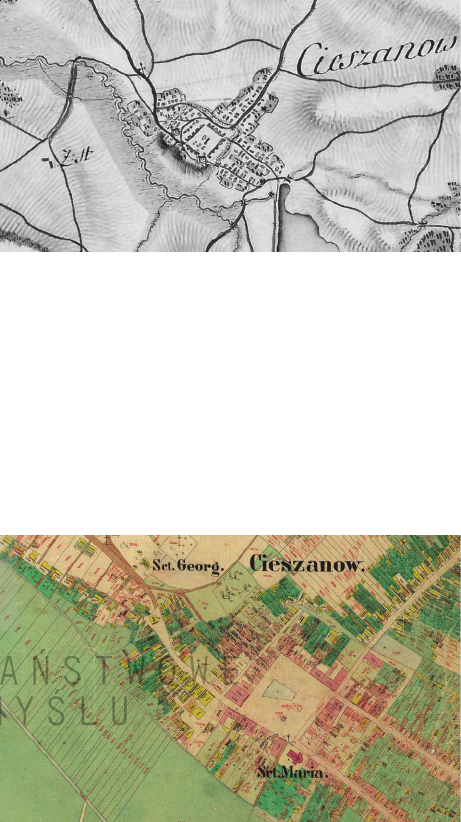

This study analyzed the urban layouts of three Renais-

sance towns founded in the territory of contemporaneous

Lesser Poland and that represented the commercial settle-

ment type and are currently located in three dierent voi-

vodeships: Zakliczyn (Lesser Poland Voivodeship), Cie sza -

nów (Subcarpathian Voivodeship) and Raków (Holy Cross

Voivodeship).

Zakliczyn

Zakliczyn is located in the Rożnów Upland, on the right

bank of the Dunajec River. In terms of administration, it

is located in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship, in Tarnów

County, and is the seat of an urban-rural municipality.

The town was founded in 1558 close to Melsztyn Cas-

tle, by Spytko Wawrzyniec Jordan [18, p. 296], [19], based

on the Magdeburg law [20, p. 182]. Previously, the town’s

territory had been occupied by the village of Opatkowice,

which belonged to the Benedictine monastery in Tyniec.

The Jordan family received this land from the monks by

means of property exchange.

The town had a favorable location along a trade route

that ran along the Dunajec and along the route that con-

nected Biecz and Cracow, which is why it developed well

and relatively quickly. Around 20 years after its founding,

the town already featured a bath house, two grain mills

and a fulling mill. Shortly afterwards, a town hall was also

erected on its market square [20, pp. 180, 181].

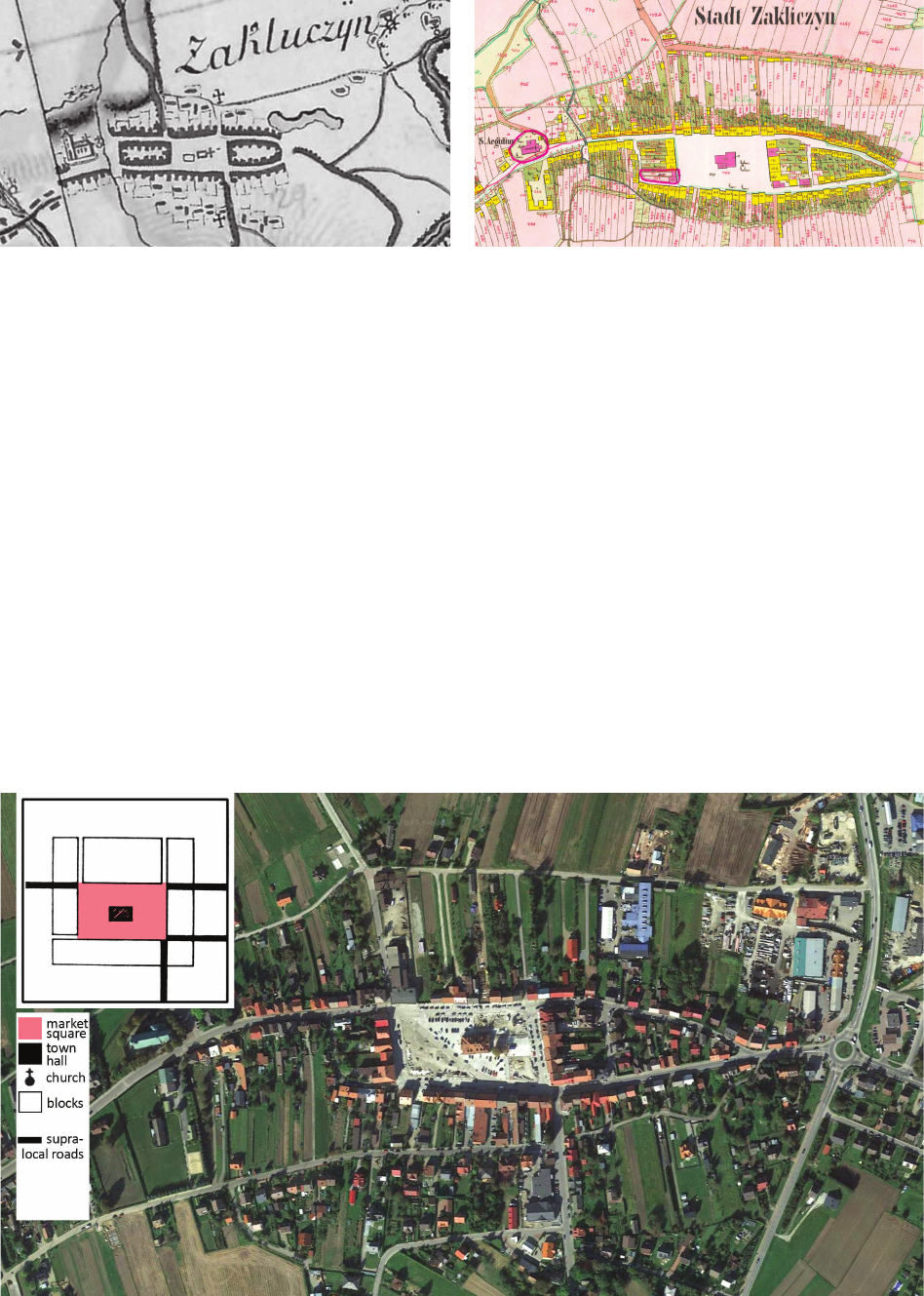

Zakliczyn’s urban layout was probably delineated based

on the short schnur unit of measurement, which was 37 m

long. At the center of the town, a rectangular market

square was delineated, measuring ca. 170 × 100 m. Sin-

gular town blocks were demarcated around the market

square. The northern block was markedly deeper than the

others, as here the settlement plots transitioned into elds

used by the settlers. This clearly indicates an agrarian use,

which, apart from commerce and crafts, was signicant

in Zakliczyn.

Circulation trails in Zakliczyn’s urban layout were based

on seven streets that extended from the market square, of

which three had primary signicance, while the others

were merely local streets (see Figs. 1–3).

The (originally wooden) parish church of St. Giles was

located outside of the urban layout as founded, which was

associated with its pre-founding age.

Zakliczyn changed owners several times. After the Jor-

dan family, it belonged to the Zborowski, Sobek, and Tarło

families. The latter were the founders of a monastery of

the Reformed Congregation of Friars Minor, which was

erected in 1622 [19].

The town, considering the previously discussed typology

of Renaissance towns established in historical Lesser Po-

land, represents the commercial type that acted as a mar-

ket for the region and surrounding villages that belonged to

the Jordan family. It should also be noted that Zakliczyn’s

plan allows us to classify it as a settlement delineated using

a traditional, medieval form of urban space organization.

A review of archival maps that feature Zakliczyn (the

First Military Survey – Map of Galicia and Lodomeria of

1769–1783, the Galician Cadaster of 1848, the Second Mil-

itary Survey – Map of Galicia and Bukovina from 1861–

1864) and up-to-date survey documentation of the town

indicated that its original urban layout, which emerged

during the period of its founding in the mid-16

th

century,

has mostly survived into the present. Its inarguable values

are evident in the fact that its urban layout is listed in the

register of monuments of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship

(entry no. A-21) based on a decision issued in 1976 [21].