56 Joanna Jadwiga Białkiewicz

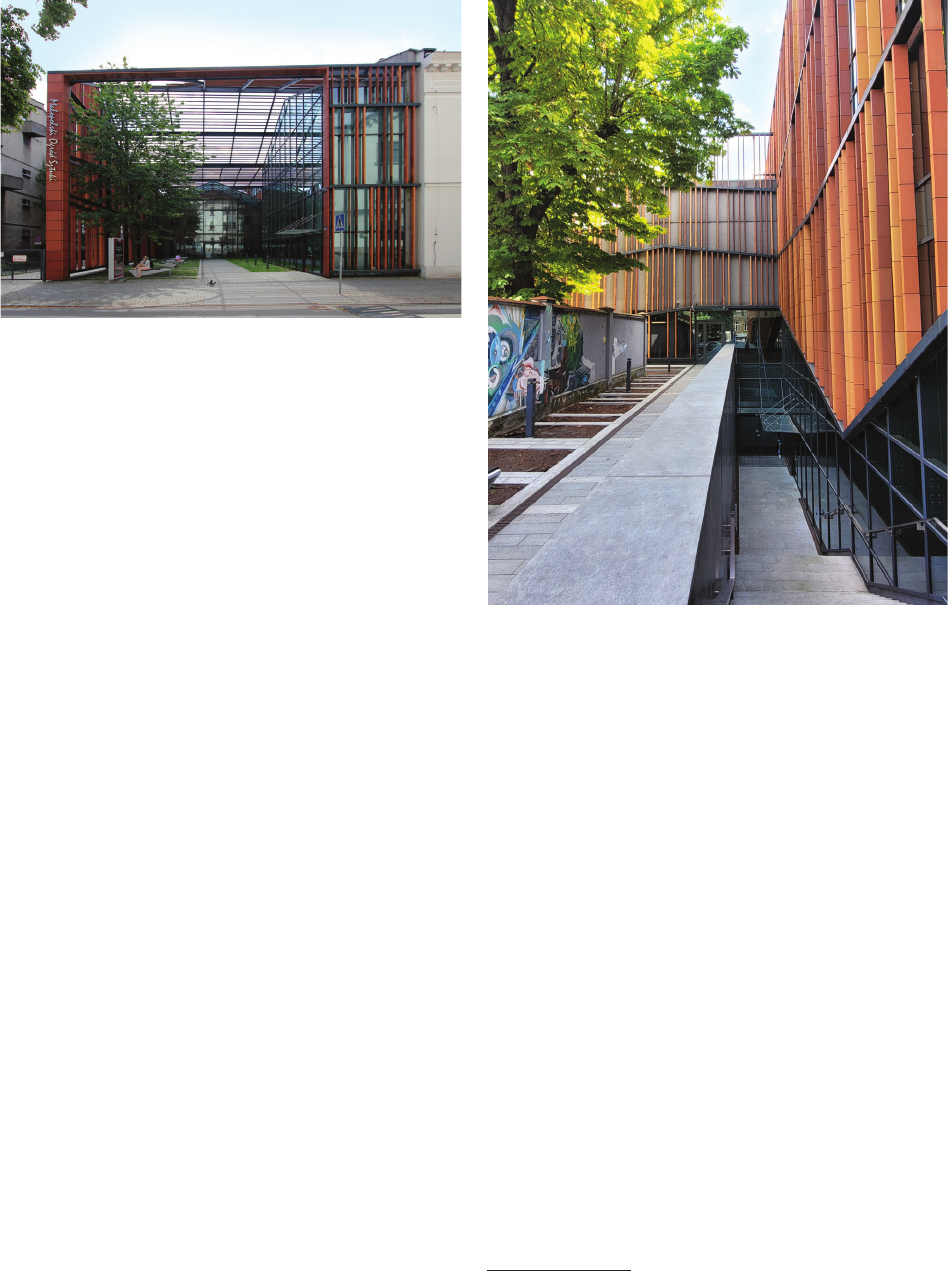

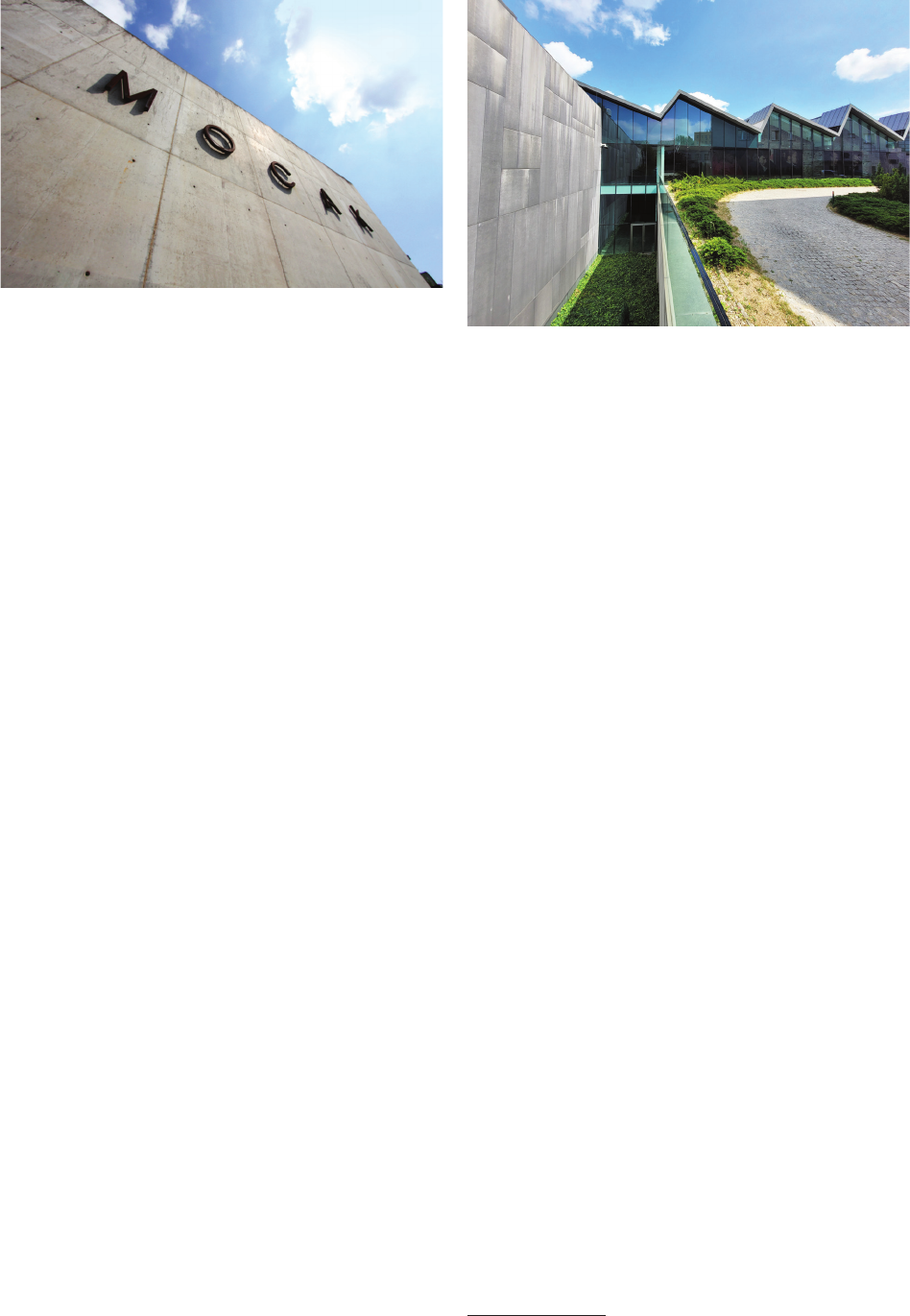

architects also use material references (brick in the MOS

project). Moving on to increasingly metaphorical refer-

ences, another method of establishing a connection with

the environment is to take a particular motif from the ex-

isting architecture, which is creatively introduced into the

new building. An example is the shed roof in the MOCAK

project. All of the aforementioned projects are also linked

by the use of glass as a means of linking new buildings

to the context of the site. Glazing not only adds visual

lightness to the buildings, but above all acts as a kind of

connector with what is outside, fostering the blurring of

boundaries between the new edices and their surround-

ings. To some extent, contemporary buildings become

“transparent” both literally and metaphorically. Architects

symbolically allow history to be reected in the glass

panes of modernity, proving that a modern block does not

have to alienate itself, but can blend harmoniously with its

surroundings. The most non-literal and “abstract”, and at

the same time the most advanced reference to the context

is the symbolic charge of the form of the new objects. At

this stage, the creative process has already gone far be-

yond simply adapting to the site as it is seen in the concept

of optimization. In order to encode symbolic content in

architecture, an idea in the designer’s mind is necessary.

At the same time, this metaphorical charge enhances the

quality, and thus the iconic potential, of the work. Sym-

bolic references can be made on various levels. In the case

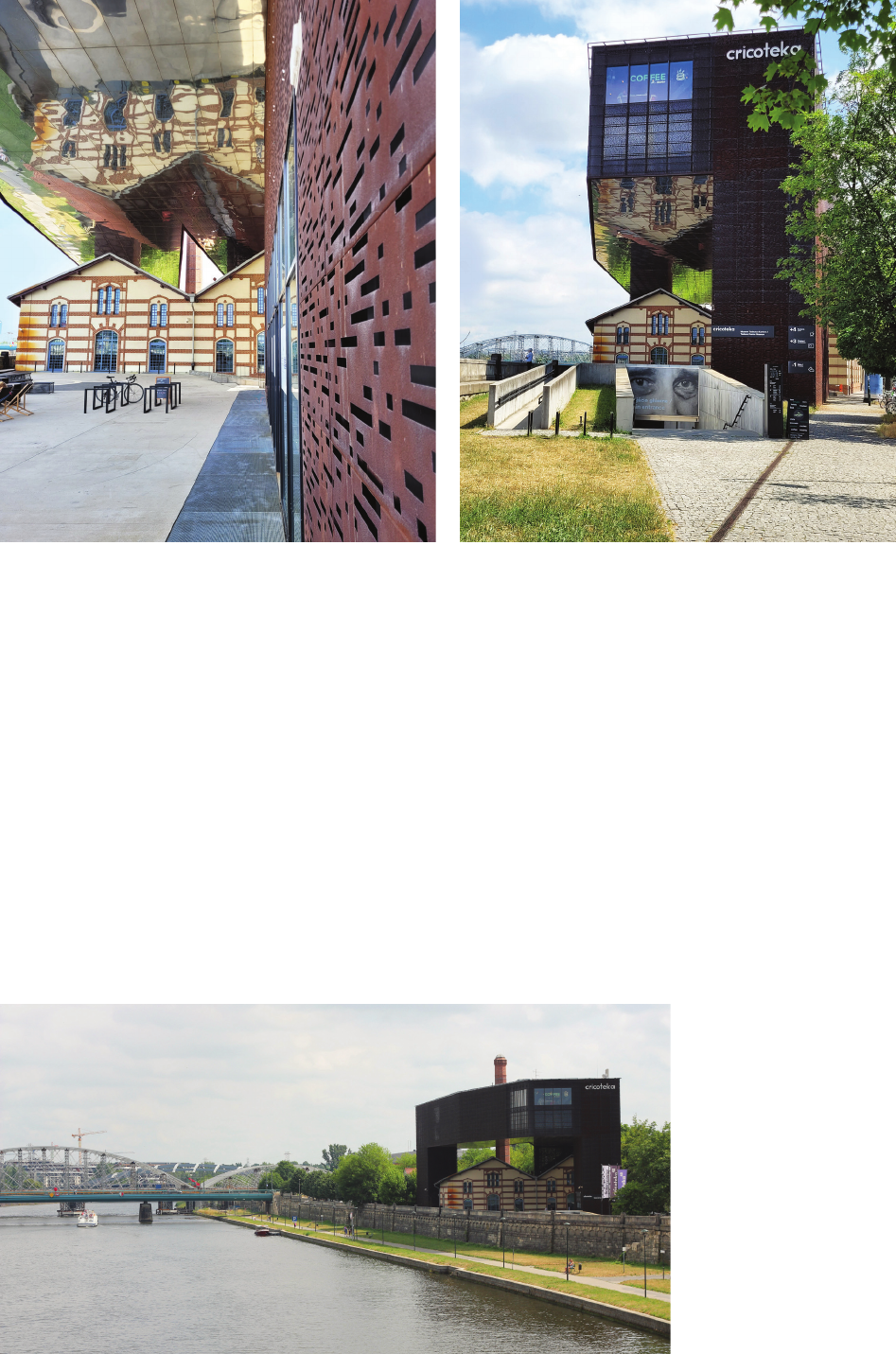

of Cricoteka, we are dealing, among other things, with the

form of the building evoking associations with the works

of Kantor and with a reference to the idea of ambalage

(the new edice “wraps”, as it were, the historic buildings

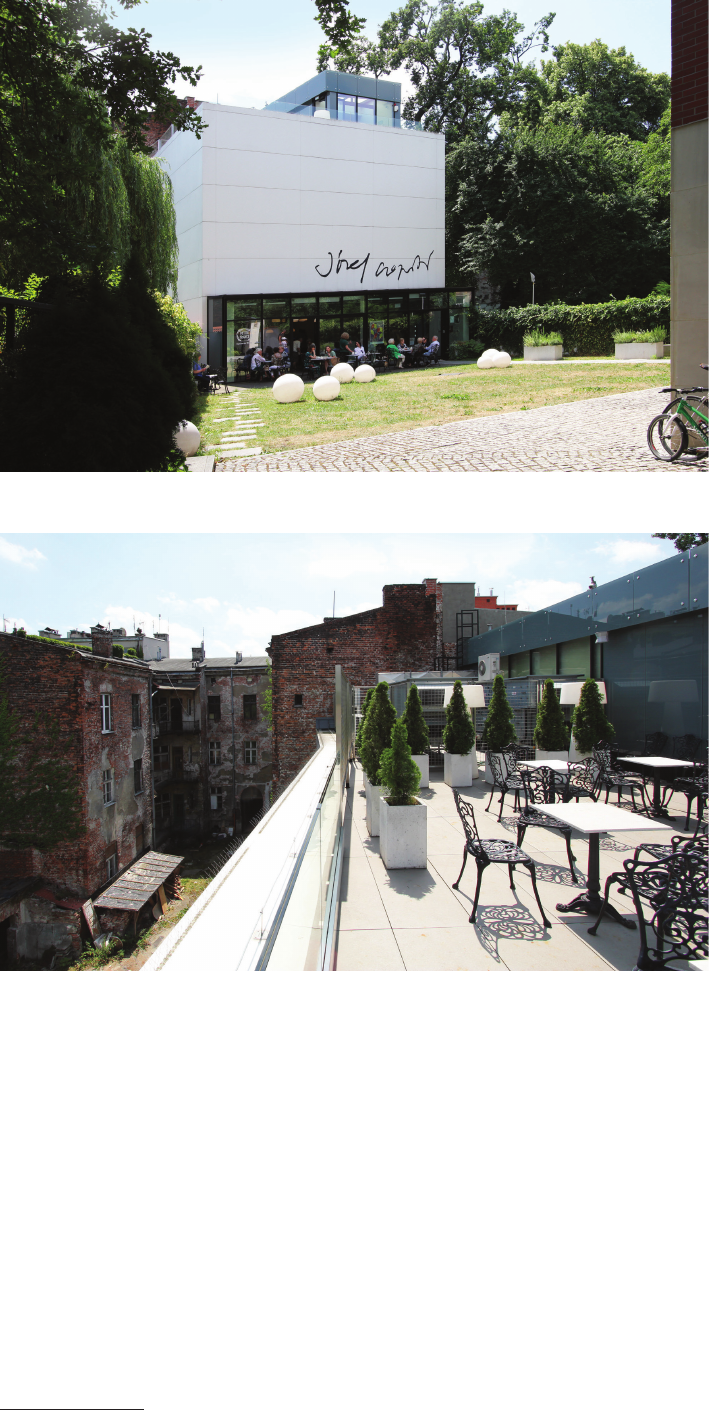

of the Podgórze power plant). In the Czapski Pavilion, the

white façade-screen can be interpreted as a blank canvas,

symbolically open to any kind of art, transferred to it by

means of modern technologies. The Aviation Museum

contains references to the idea of ying in its body. What

is appropriate for symbols, all these references are ambig-

uous and open to interpretation, leaving the viewer a great

deal of freedom in their individual search and reading.

As Ingarden writes, contextualism is neither a design

method nor an architectural style, it is a denition of the

relationship between the designed structure and its local

background [11, p. 320]. The aim of contextual architec-

ture in urban space is to inscribe itself in the continuity of

its history. The new building must “speak” in the language

of forms and meanings understood locally, as the architect

of the Małopolska Garden of Art emphasizes, the task is to

avoid semantic chaos and maintain the cultural continuity

of the place by adding and marking the presence of con-

temporary forms. Ingarden refers to this as “abstract con-

textualism” and links it to Kenneth Frampton’s “critical

regionalism”

5

. Adopting such a design philosophy makes

it possible to create objects that are globally modern in ex-

5

The denition of “critical regionalism” was developed by

K. Framp ton in the 1970s–1980s. According to Frampton, the most

interesting buildings are created at the intersection of local and global

architecture, so they are open to technological advances and at the same

time rooted in local traditions, creating a space that is understood and

approved by local communities.

pression and at the same time rooted in local tradition, and

thus acceptable in historical space. Urbańska uses the term

“sitespecic architecture” [22] or “the architecture of dia-

logue” [23] to describe the same phenomenon. Regardless

of the nomenclature adopted, the key is the attitude to the

context of the place, which is neither a passive imitation

nor an arrogant rejection of the surroundings. Contextual

architecture in the case of the above-mentioned buildings

is the architecture of interpretation, combining respect for

the genius loci and the ambition to create a valuable con-

temporary form on this basis.

Contextual philosophy – conclusions

The contextual creative philosophy in the case of the

listed public buildings is based on combining the idea of

revitalizing a place with giving the new building its icon-

ic potential. Revitalization takes place both literally by

modernizing the historic building and by giving the place

a new meaningful content and quality. The context of the

place and the associated conditions for the architect are

both the framework and the matter of the creative pro-

cess. The goal is to combine the concepts of continuation

and modication so that a completely new quality is cre-

ated. The essence of the creative method here is to treat

the site context and its accompanying formal constraints

in terms of inspiration for the liberation of an original

idea. In a context treated with respect, the architects in-

troduce modern forms, technologies and materials, giving

the whole a highly original character. In all the projects

described, the past and the present interact, with the past

becoming inspiration and material, and modernity giv-

ing history a new life and meaning. Despite being rmly

rooted in the historical context, all the projects mentioned

are characterized by originality and modernity of form.

It manifests itself in the atypical shape and layout of the

mass (especially Cricoteka, MOCAK, Aviation Museum),

the use of modern materials and technologies, or the orig-

inal treatment of traditional materials (MOS elevations).

Each time we are dealing with a modern architectural

form, which does not compete and does not dominate the

historical buildings, but ts harmoniously into it, creating

a distinctive whole. It is this combination, which is both

coherent and creates a new quality, and therefore incor-

porates both the concept of optimization and the idea of

iconic architecture, that should be considered the main

achievement of the designers of the listed edices. Con-

textualism in this sense becomes an answer to the question

of the meaning of the architect’s work in modern times,

in a situation of intensive development of technology and

articial intelligence, as well as his role in the complex

system of architectural conditions, which consists of le-

gal, nancial, environmental or social considerations. The

architectural profession is evolving away from engineer-

ing and towards concept creation. This is particularly no-

ticeable in the case of public buildings, which are required

to be noticeable and present a high quality of form. At the

same time, the form in this case cannot be freely generat-

ed by the imagination of the designer, but must take into

account a whole range of conditions. Thus, the rst task