4 Ewa Cisek

przestrzenne, nie przesłania jednak uroku architektury

norweskich Saamów (sam. sápmi). Reprezentuje ona

znacznie mniejszą skalę, jest skromna w swej prostocie,

bliska naturze i aż do lat 80. XX w. pozostawała prawie

niezauważalna. Sytuacja ta wiązała się z niechlubną prze

szłością kraju, kiedy ta rdzenna ludność zamieszkująca

jego północne rejony poddawana była przez ówczesny

norweski rząd procesowi długofalowej norwegizacji.

Efektem tych działań było nieuchronne niszczenie rodzi

mej mowy, religii, tradycji i zwyczajów, a ostatecznie na

rodowej tożsamości. Szkody takiej polityki wydawały się

nieodwracalne. Dopiero wiele akcji przeprowadzonych

przez saamskich patriotów

2

, w tym ostry protest Saamów

i norweskich ekologów z ekolozofem Arne Næssem

na czele przeciwko utworzeniu tamy na rzece Altaelva

(sam. Álttáeatnu) koło miasta Alta (w latach 1979–1981),

grożącemu zalaniem cennych pastwisk dla reniferów

3

,

zwróciły oczy całego świata na wyjątkowy lud, który za

cięcie walczył o prawo do ochrony swojego terytorium

i żyjących na nim zwierząt. Duże znaczenie dla kultury

ludu Saam miało rozwinięcie w niej ustnej tradycji lite

rackiej, na którą składały się legendy, baśnie

4

i poezja

recytowana w formie tradycyjnych pieśni. Znaczący

wkład w propagowanie tych ostatnich wniosła świato

wej sławy saam ska wokalistka Mari Boine, dzięki której

tradycyjny śpiew joik

5

, należący do najstarszych w Euro

pie, mógł być usłyszany poza granicami Norwegii. Istot

ne dla utrzymania i odradzania się kultury regionu były

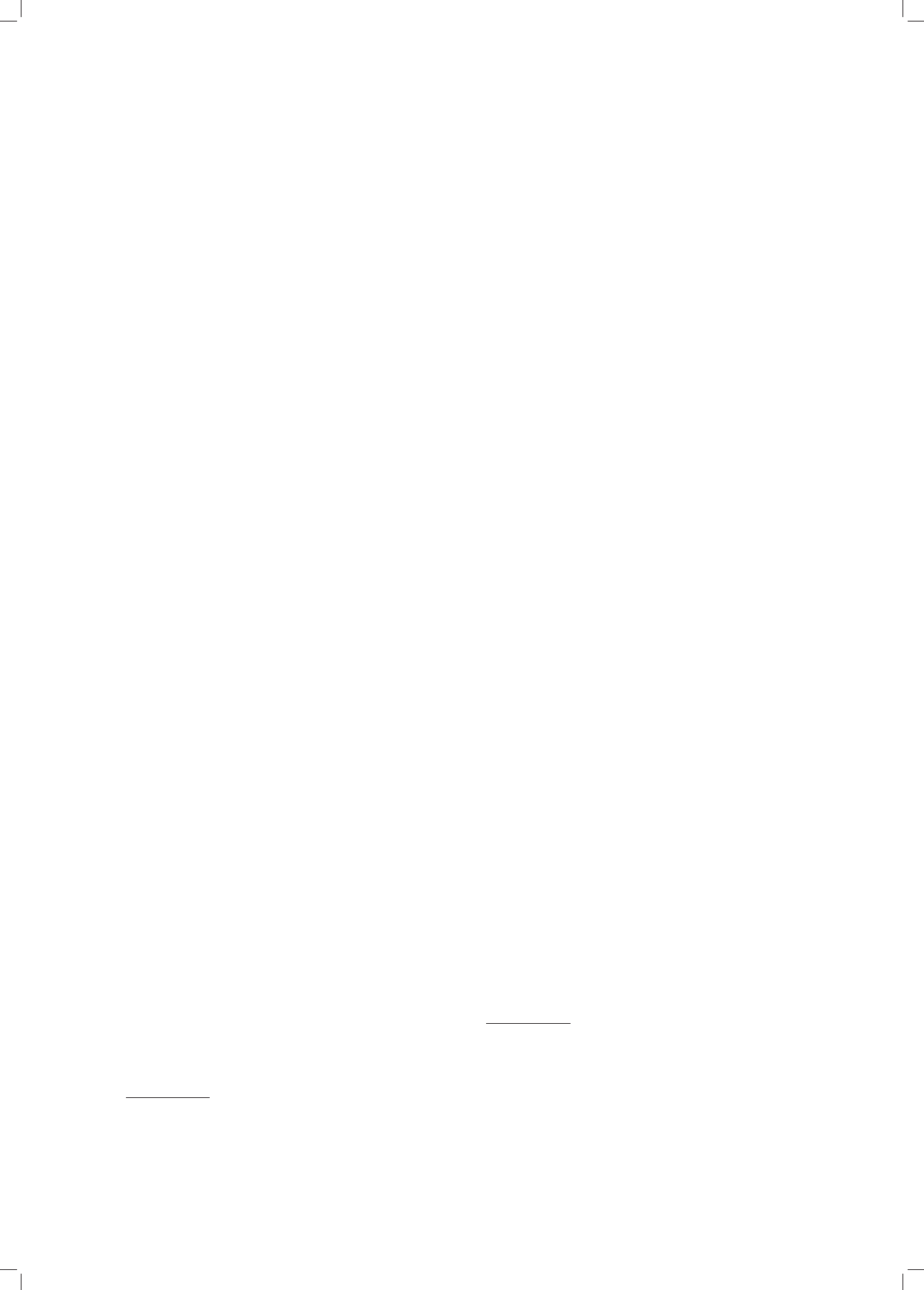

także materialne pozostałości tradycyjnych konstrukcji

mieszkaniowych lavvo i drewnianoziemnych, krytych

darnią turf hut. To głównie dzięki nim kultura ta przetrwa

ła i mogła się na nowo odbudować, czerpiąc z pierwot

nych wzorców inspiracje do współcześnie powstających

obiektów.

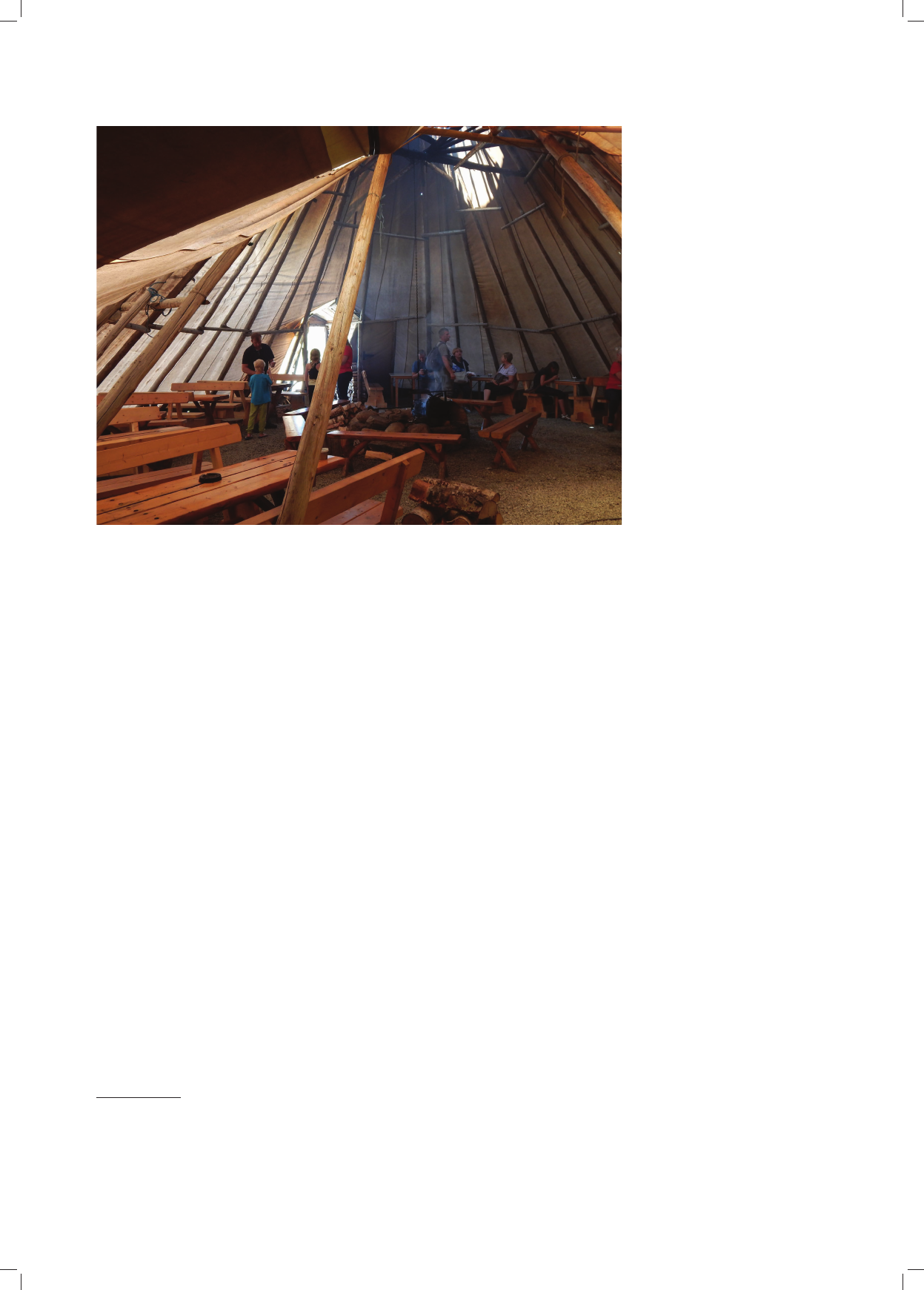

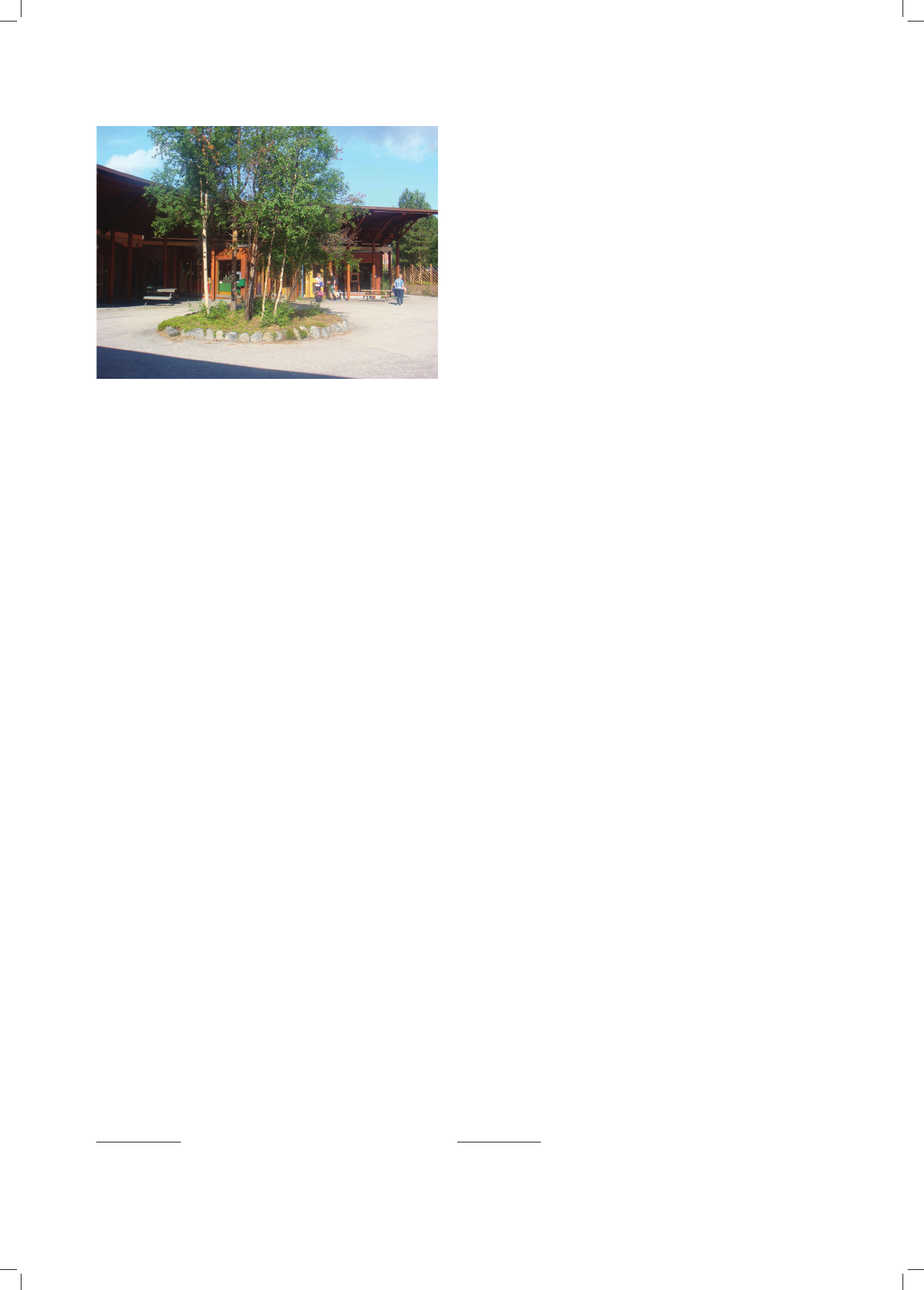

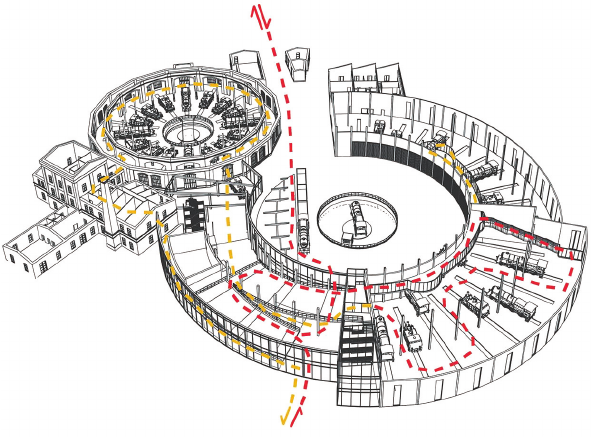

Począwszy od lat 60. XX w. zrealizowano wiele sa

amskich budowli z przeznaczeniem na centra kulturalne,

muzea, warsztaty rękodzielnicze, szkoły, hotele i lokale

gastronomiczne. Architektura tych współcześnie kreowa

nych obiektów, chociaż odznacza się wykorzystaniem

wysoko zaawansowanych technologii, zdaje się wyrastać

z tradycyjnego sposobu organizowania miejsca zamiesz

kania Saamów zarówno co do jego planu, jak i archetypo

wych, spiczasto zwieńczonych lub pokrytych darnią form

obiektów. Realizacje te wyraźnie nawiązują do wątków

2

Przełomowym wydarzeniem był dzień buntu Saamów przeciwko

dyskryminacyjnej polityce miejscowych przedstawicieli władzy w Kau

to keino (8.10.1852). Mimo że został on krwawo stłumiony, kolejne lata

przyniosły czas większej akceptacji Saamów w Norwegii [2, s. 2].

3

Chodziło o obszary rozciągające się wokół wioski Masi (sam.

Máze) pomiędzy Guovdageaidnu a Altą. Teren zamieszkany jest przez

kilkaset osób i kilkadziesiąt tysięcy reniferów. W wyniku presji opinii

publicznej i protestu ekologów (występuje tam, jako w jedynym miejscu

na świecie, rzadka, chroniona roślina z gatunku masimjelt) plany bu dowy

zapory zmodyfikowano i rejon ten nie został zatopiony [3, s. 97, 100].

4

Legendy i baśnie Saamów zostały spisane na początku XX w.

przez J.K. Ovigstada. Wątki te pojawiają się również we współczesnej

literaturze np. saamskich pisarzy: Mario Aikio i Ailo Gaupa oraz poe

tów: Nilsa Aslaka Valkeapää i Rauniego Magga Lukkariego [4, s. 89].

5

Sam. joik – oznaczał tyle, co wyrażenie śpiewem kogoś lub cze

goś, z wyłączeniem imienia lub nazwy tego, do kogo był kierowany.

Śpiew ten wykonywany był a cappella [3, s. 113].

modest in its simplicity, close to nature, and until the

1980s it remained almost unnoticed. This situation was

connected with the disgraceful past of the country when

this native population living in its northern areas was sub

jected to the longterm Norwegisation process by the Nor

wegian government. The effect of these actions was the

inevitable destruction of the native speech, religion, tradi

tions and customs, and eventually the national identity.

Harmful effects of this policy seemed irreversible. Only

a lot of actions which were carried out by the Saami pa

triots

2

, including the violent protest of the Saami people

and Norwegian ecologists along with ecologist and phi

losopher Arne Næss against the construction of a dam on

the Altaelva River (sam. Álttáeatnu) near the city of Alta

(1979–1981), which could flood valuable reindeer pas

tures

3

, drew the world’s attention to those unique people

who fought for the right to protect their territory and ani

mals living within it. The development of oral literary tra

dition in it, which included legends, fairy tales

4

, and poet

ry recited in the form of traditional songs was of great

importance. The worldfamous Saami singer Mari Boine,

thanks to whom traditional singing joik

5

which is the old

est in Europe could be heard beyond the borders of Nor

way, contributed significantly to the promotion of

the latter. Material remnants of traditional housing struc

tures lavvo and woodendirt turf hut dwellings were also

significant for the preservation and revival of the region’s

culture. It was mainly thanks to them that this culture

survived and could be rebuilt deriving an inspiration

for building contemporary objects from original patterns.

Since the 1960s, many Saami buildings have been con

structed to be used as cultural centres, museums, handi

craft workshops, schools, hotels, and restaurants. The

architecture of these modern objects, although it is cha

racterised by the use of highly advanced technologies,

seems to stem from the traditional way of organising the

Saami place of residence both in terms of its plan and its

archetypal, spiked, or turfcovered forms of objects.

These realisations explicitly refer to cosmological ele

ments that are also visible in the detail colour in which

additionally animalistic motifs appear. In 2000 a new seat

of the Saami Parliament (in Norwegian Sametinget) was

erected in Karasjok, which constitutes an advisory body

2

The breakthrough event was the day of the Saami people revolt

against the discriminatory policy of the local authorities in Kautokeino

(8.10.1852). Although it was bloody suppressed, the subsequent years

brought more acceptance of the Saami people in Norway [2, p. 2].

3

It referred to the areas around the village of Masi (Máze) between

Guovdageaidnu and Alta. The area is inhabited by several hundred peo

ple and tens of thousands of reindeer. As a result of the public opinion

pressure and ecologists’ protest (the only place all over the world where

a rare, protected plant of the species masimjelt grows), the dam construc

tion plans were modified and the area was not flooded [3, pp. 97, 100].

4

The Saami legends and fairy tales were written down in the early

20

th

century by J.K. Ovigstad. These plots also appear in contemporary

literature, for example, by Saami writers such as Mario Aikio and Ailo

Gaup, as well as by poets Nils Aslak Valkeapää and Rauni Magga Lukati

[4, p. 89].

5

In Saami joik – meant expressing somebody or something by sing

ing, excluding the name of the thing or person to whom it was dire cted.

This singing was performed in the form of a cappella [3, p. 113].