ExploringŁódź’scitycentre–fromtheoriginstomoderntimes 77

of the peripheries, where the poorer population was con-

centrated. Over half a century of inactivity by the tsarist

authorities transformed Łódź into a city characterized by

urban chaos. It was only between 1906 and 1915 that the

suburban areas were incorporated into the city (Stawi

szyńska 2019). The pursuit of creating an integrated and

functional centre continued to challenge urban planners

and decision-makers in the following years. As a result,

Łódź developed into a city with a seemingly organized ur-

ban structure, reecting its dynamic historical evolution.

Pre-war/post-war visions of city centre

Compared to other Polish cities, Łódź experienced re

la tively minimal destruction during World War II. Conse-

quently, Łódź was designated as the temporary capital of

Poland during the reconstruction of Warsaw, which had

been devastated by the war. Despite the tragic circum-

stances, this period was pivotal in the city’s history, of-

fering an opportunity to transform the down-town area

into a modern centre after more than 500 years since its

founding. The Nazis sought to integrate new composition-

al axes into the existing urban layout of Litzmannstadt.

Their vision included the development of wide boule-

vards and squares along what is now the Łódź W–Z route

(Eng. Łódź east–west route). This planned axis was to be

adorned with monumental buildings designed to symbolize

the power and inuence of the Third Reich. The new town

hall, the monument to General Litzmann on Manifestation

Avenue, Art Avenue, and the Welcome Square near Łódź

Kaliska Railway Station were intended to signify a shift in

the prevailing urban aesthetics. The plan also included the

creation of Manifestation Square, designed to host mass

gatherings and propaganda events. However, most of these

ambitious projects were never realized due to the defeat of

the Third Reich in the war (Bolanowski 2013).

After the Nazi occupation, the Communist authorities

took over Łódź and aimed to implement their own urban

planning vision. A key component of their strategy for

the city centre was to establish a clear central axis along

Stalin Avenue (now Piłsudski Street). This approach par-

tially continued the Nazis’ scheme to extend the urban

development from Łódź Kaliska Train Station) to Ry-

nek Wodny (Eng. Water Market). Surrounding the axis,

it was envisioned that monumental party buildings, cul-

tural institutions, and other structures would emerge to

symbolize the power of the working class. In the central

part of the parade square, a building comparable to Pałac

Kultury i Nauki (Eng. the Palace of Culture and Science)

in Warsaw was planned, whose dominance in the space

was intended to be prominent in the city’s skyline. The

functions of the urban space were aligned with the prin-

ciples promoting more or less enforced social integration.

This concept can be described as coherent but also as im-

posing a direction for the further development of urban

structures. Among other things, it included a redenition

of the city’s image, which undermined the signicance of

the historical core (Sumorok 2010).

Despite this, Łódź’s most pressing issue during this

period was the inadequate housing conditions, the short-

age of public utility buildings, and the lack of technical

infrastructure. In the 1940s, the city’s administrators pro-

posed a development plan for the Bałuty district, located

near the city centre. The Bałuty concept was reminiscent

of the Kraków district of Nowa Huta, known as a garden

city, based on the idea of Ebenezer Howard (Motak 2016).

Each of the ve neighbourhoods, designed as green ur-

ban blocks, was intended to include its own local com-

munity centre to address the needs of the residents. How-

ever, during this period, most residential developments

occurred outside the city centre. This was evidenced by

the newly developed neighbourhoods in New Rokicie and

Doły. Moreover, the redevelopment of the railway con-

necting the peripheral districts with the city centre, along

with the integration of the ring railway and the planned

radial tunnel, was intended to enhance both intra- and in-

tercity connections (GralińskaToborek 2016). Despite

signicant needs, only a few of these plans were realized,

as Łódź was not considered a priority area by the central

authorities at that time. A turning point came in the 1970s

when Edward Gierek’s initiative for national moderniza-

tion allowed for a spatial redenition of the downtown.

During this period, several key structures were built, in-

cluding the oceservice complex along Piłsudski Street,

Dom Handlowy Central (Eng. Central Department Store),

or Szpital Ministerstwa Spraw Zagranicznych i Adminis-

tracji (Eng. the Ministry of Internal Aairs and Adminis-

tration Hospital). The development of the city was also

signicantly inuenced by the conceptualization and par

tial realization of university campus plans, which contri-

buted to shaping Łódź’s prole as an academic centre.

Du ring that time, the housing sector experienced signi

cant growth. Zespół Śródmiejskiej Zabudowy Mieszka

niowej (Eng. the Down-town Residential Complex) was

constructed there. This development features high-rise

apartment buildings whose architectural style and urban

character distinctly contrast with the city’s traditional

architecture. This was intended to project a modern and

dynamic image for Łódź. Over time, it was recognized

that high-rise residential buildings were not the optimal

solution, inuencing subsequent urban development di-

rections. Nevertheless, the complex remains a signicant

part of Łódź’s urban landscape, reecting the city’s ambi-

tions for high-rise construction (Ciarkowski 2016).

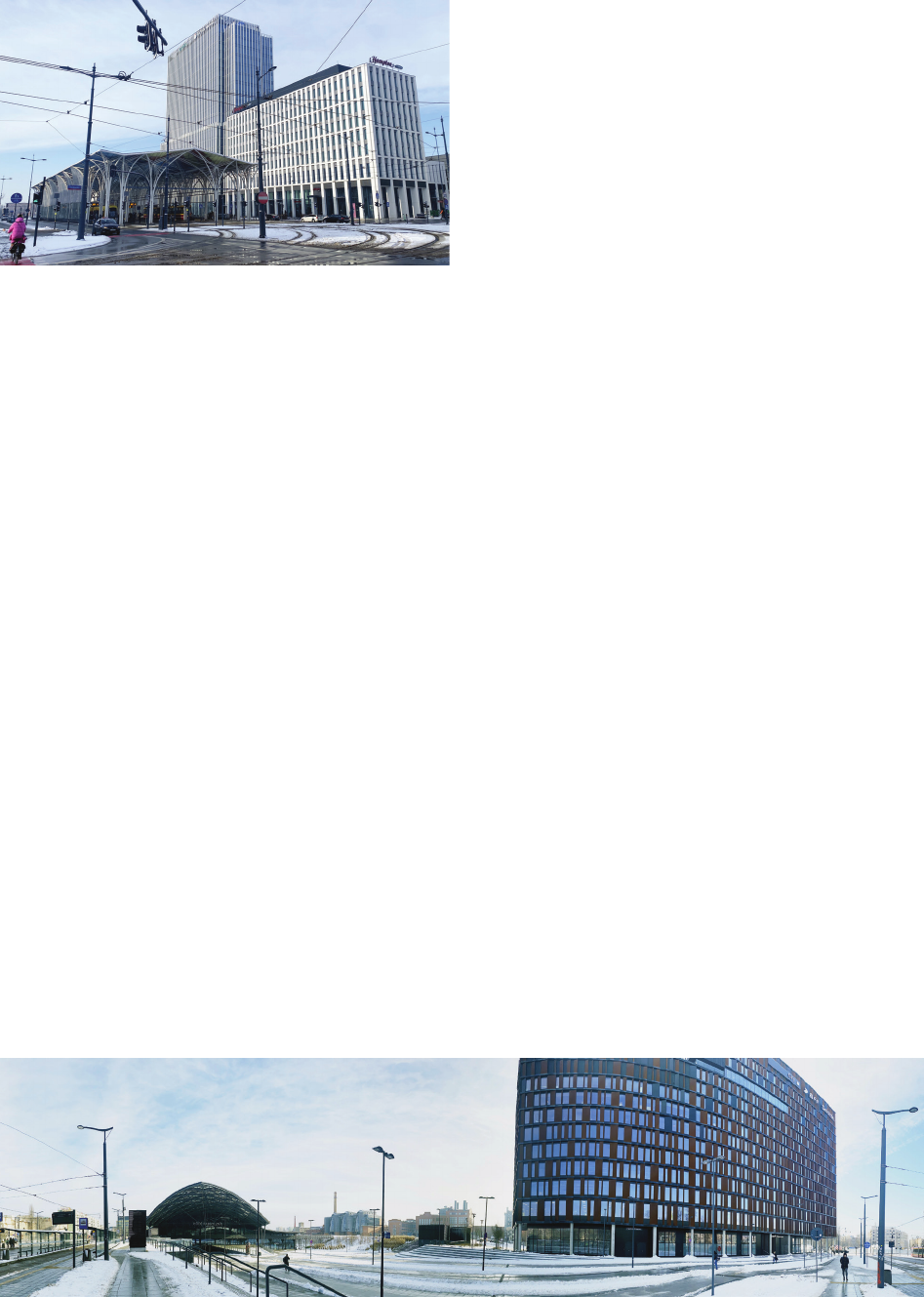

The communist period of Poland’s history is often crit-

icized for disregarding the value of existing urban struc-

tures, but the ideological heritage of that era is currently

undergoing processes of modernization and adaptation to

contemporary needs. The area once designated as Stalin

Avenue now functions as a primary transportation artery of

the city. A high-rise complex designed for residential and

oce purposes have been developed along this avenue.

The site of the Sovietproposed skyscraper is now oc-

cupied by a public transit hub, similar in its shape to Lis-

bon’s train station – Gare de Oriente (Majewski 2016).

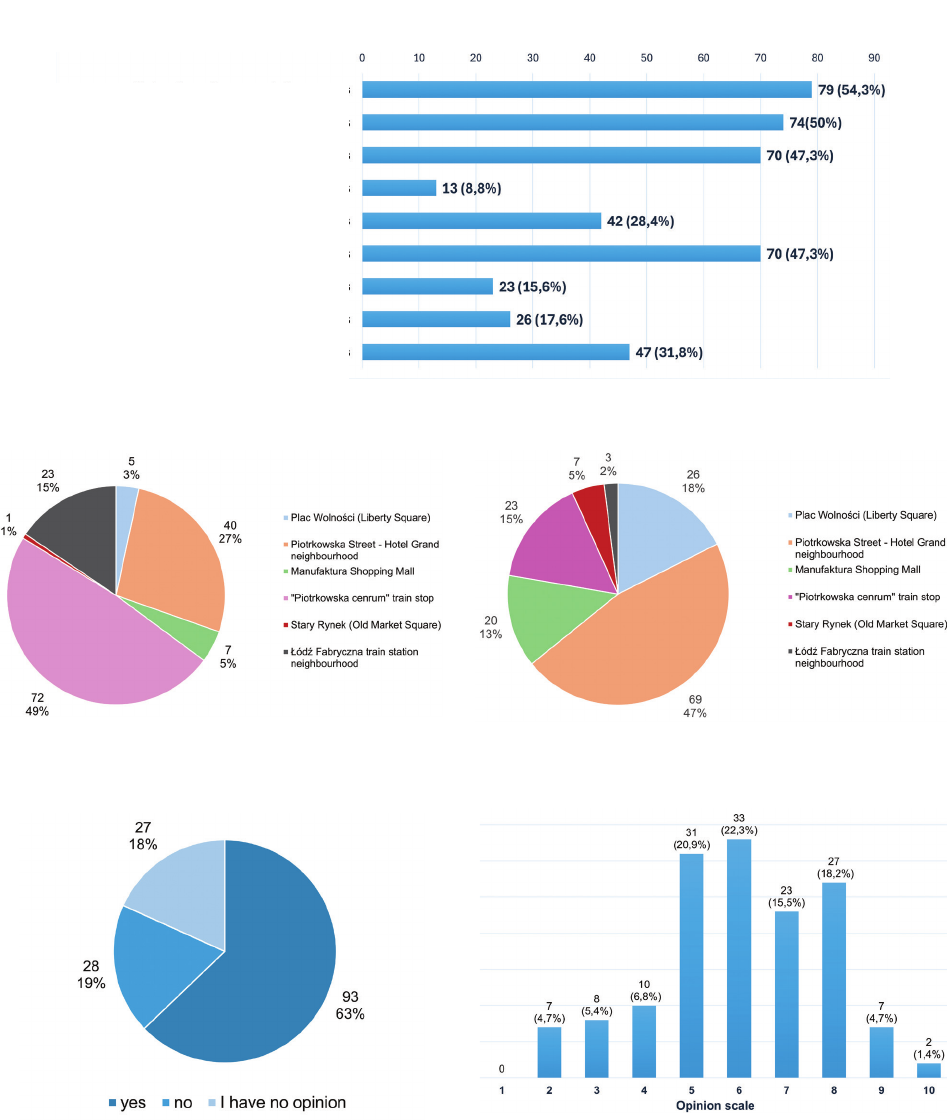

The area around the “Piotrkowska Centrum” train stop

(see Fig. 2) is characterized by signicant service, retail,

and entertainment establishments, primarily developed in

the 2

nd

half of the 20

th

century and in the 21

st

century. The

concept of a vibrant space has been preserved, but it now