Relief perspektywiczny w architekturze baroku/Illusionistic relief in Baroque architecture 31

S. Croce (ukończonym w 1685 r.) stosowano na fasadach

przeładowaną dekoracyjność wywodzącą się jeszcze

z projektów manierystycznych tego regionu, silnie zwią

zanych z wzorami romańskimi i gotyckimi.

Recepcja i interpretacje włoskiej metody

kompozycji fasad w Europie

W kolejnym pokoleniu dekorację fasad kościelnych

aranżowali tą metodą prawie wszyscy architekci europej

scy czerpiący z włoskich wzorów. Zwykle przy zachowa

niu dwukondygnacyjnej struktury dokonywano podziału

elewacji zgodnie z układem naw na trzy pola i wprowadza

no najprostsze pojedyncze, nieznacznie wysuwane przed

lico ściany pilastry (rzadko półkolumny czy kolumny),

podkreślane przez zwielokrotnienia. Projektowano tak nie

tylko skromne kościoły zgromadzeń zakonnych czy para

fialnych niewielkich miast, ale także budowle ka

tedralne

3

.

Jeszcze częściej niż pojedyncze czy perspek ty wicznie

zwie lokrotnione pilastry wykorzystywano zdwo jone podpo

ry, wywodzące się z kompozycji fasady ko ś cioła Il Gesù

4

.

W ewolucji tego układu doszło do wyraźnego wycofania

środkowej części fasady z głównym portalem i wielkim

oknem doświetlającym nawę główną lub jeszcze częściej

do silnego wysunięcia przed lico ściany bocz

nych ryzali

tów artykułujących środkową część fasady. Op tycznie two

rzyło to wrażenie rozerwania dwukondygna cyjnych porty

ków i pozostawienia ich re lik tów – zdwo

jonych podpór

flankujących główną oś fasady. Najwyraźniej ten efekt

uwidaczniał się przy zastosowaniu pełnoplastycznych

form – silnie wysuniętego belkowania na kolumnach,

nadającego fasadom nową brutalną ekspresję przez dopeł

nianie trójwymiarowych form silnie kontrastowym świa

tłocieniem

5

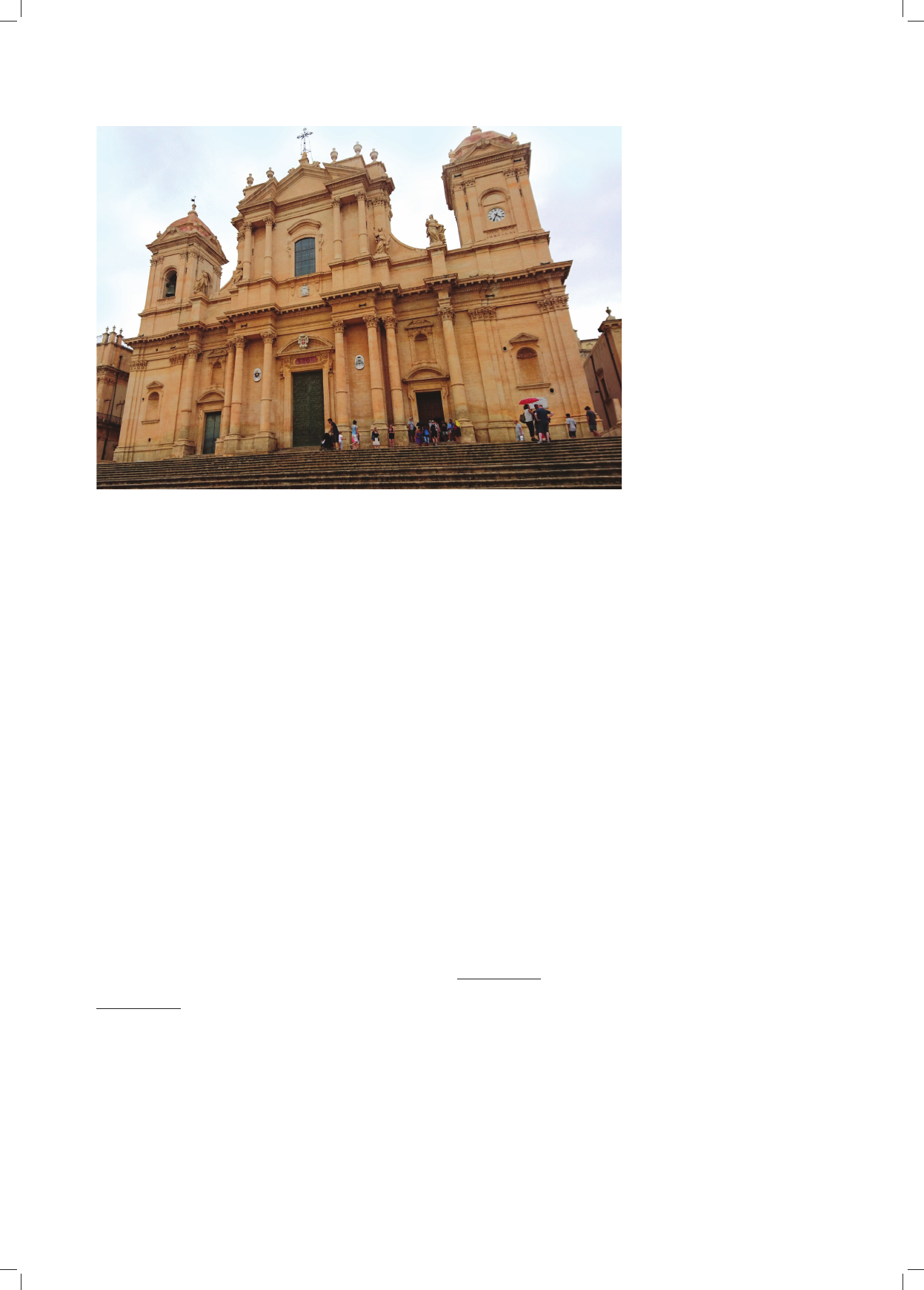

. Po raz pierwszy takie rozwiązanie pojawiło

się w wersji trójkondyg nacyjnej we Francji w projekcie

Salomona de Brosse’a dla

fasady kościoła

SaintGervais

etSaintProtais z 1616–1621

6

. W bardziej klasycznym,

3

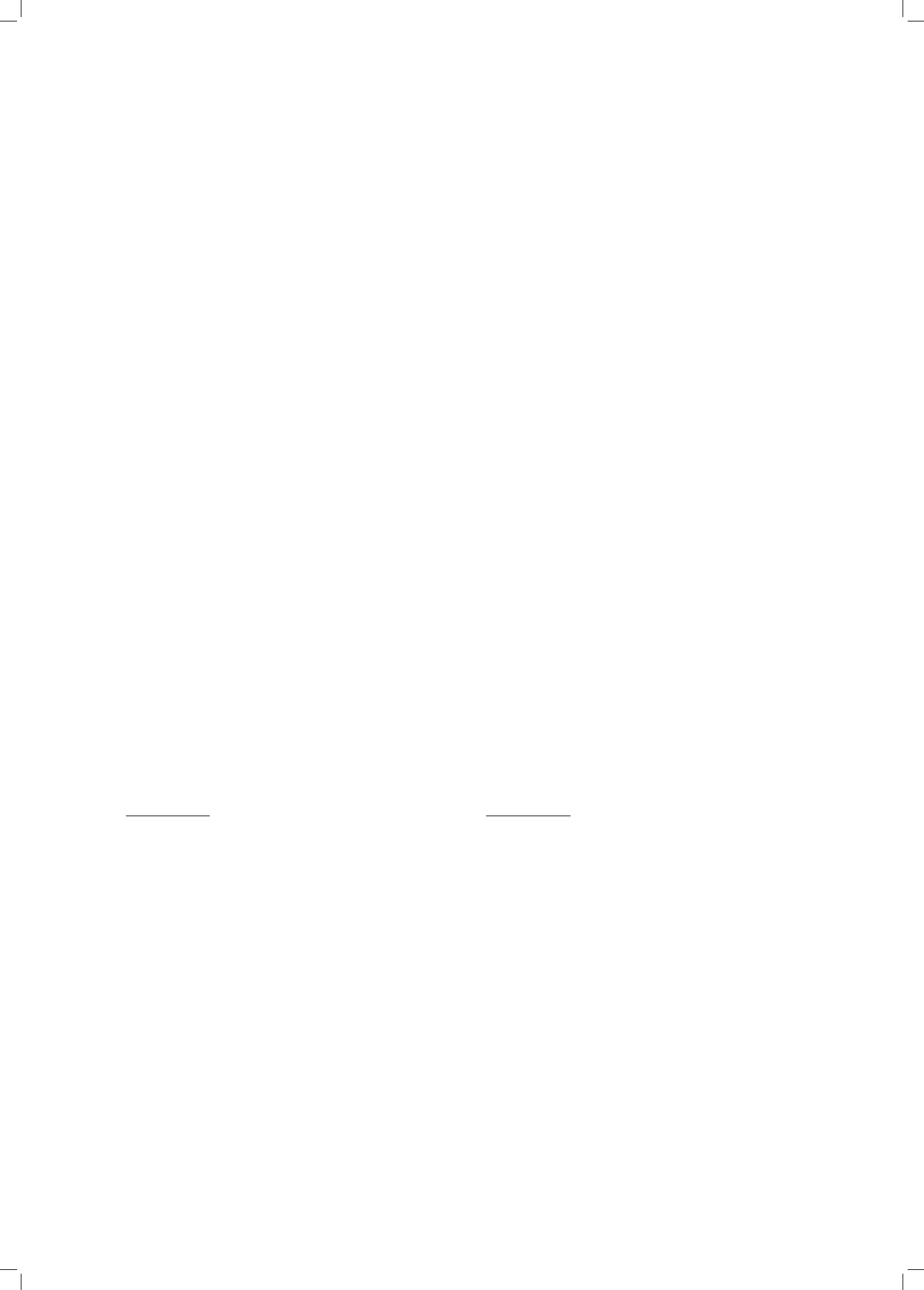

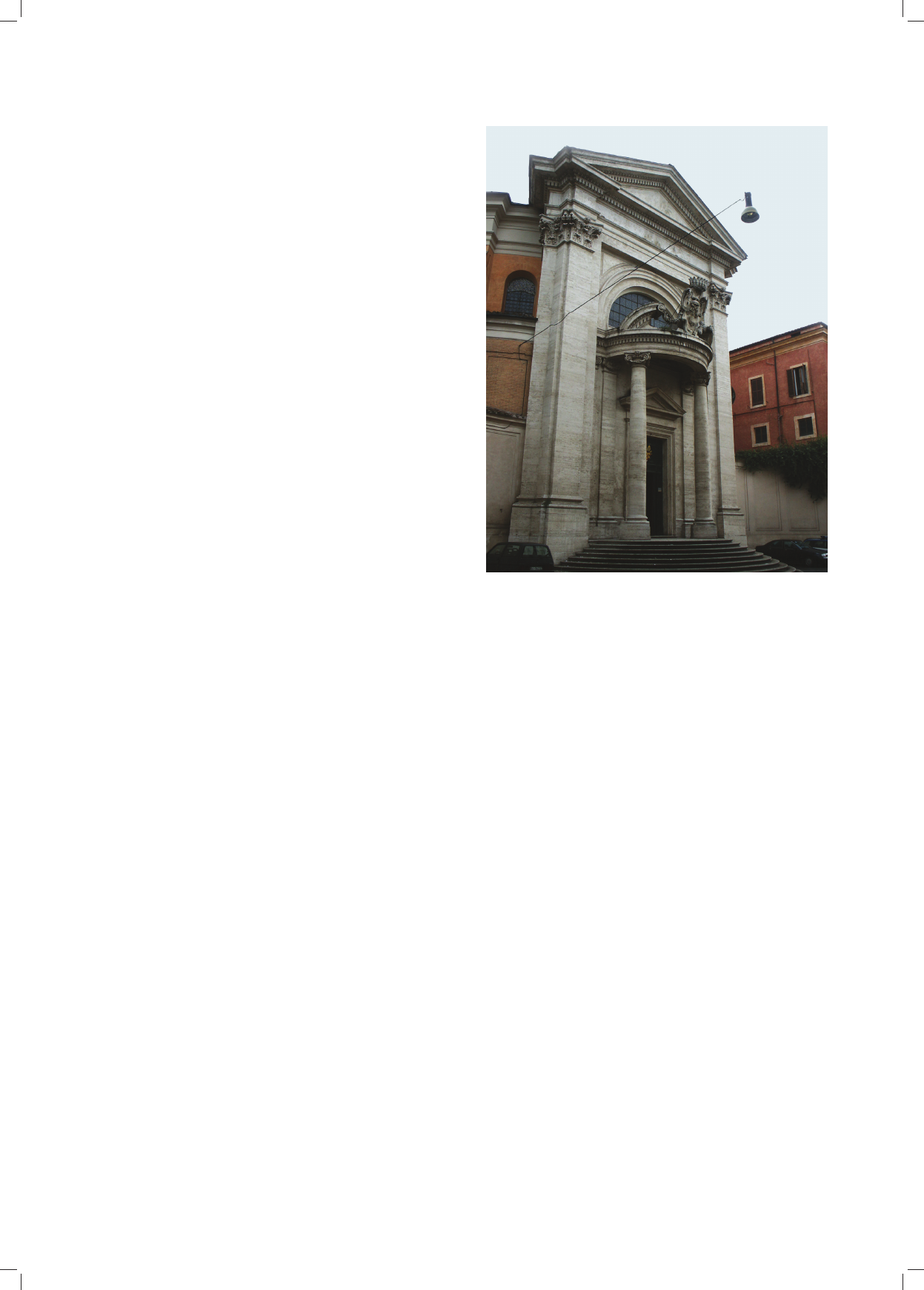

Wystarczy wymienić najważniejsze fasady – we Włoszech: np.

kościołów S. Francesco Saverio, S. Ignazio all’Olivella w Palermo, ka

tedry w Modice, kościołów S. Maurizio, S. Domenico w Martina Fran

ca, S. Irena w Lecce, S. Ferdinando i S. Carlo alle Mortelle w Neapolu,

katedry S. Agata w Galipoli, w Cervo, kościoła jezuickiego w Wenecji;

w Portugalii: w Coimbrze katedry Portalegre; w Austrii: kościoła Barm

herzigen Brüder w Linzu, franciszkanów w St Poelten, Mariahilf i do

minikanów w Wiedniu; w Czechach: kościoła w Klatovych, w Usti nad

Łabą, praskiej Lorety; w Rzeczpospolitej: fary w Poznaniu; na Litwie

i Uk rainie: kościoła jezuitów w Nieświeży; na północy Europy: kościo

ła je zuickiego StFrançoisXavier w Brugii, St Walburgi w Brugii,

a nawet protestanckiej katedry w Kalmarze i analogicznego Kościoła

Fryderyka w Karlskronie, czy dalej w Ameryce Łacińskiej: katedry

w Meksyku, Hawanie, kościoła franciszkańskiego i jezuickiego w Quito,

jezuickiego w Arequipie.

4

Jako przykład mogą posłużyć: katedra w Marsali oraz kościoły

je zuitów – w Scicli, Mediolanie, Trapani, Awinionie, Antwerpii, Lou vain,

w Pradze (św. Ignacego), Jihlavie, Lucernie, Heidelbergu, Wro cła wiu,

Krakowie (św. św. Piotra i Pawła), Wilnie (św. Teresy), Łucku i Lwo wie.

5

Wyraźnie wzorowanych na znanych przede wszystkim z traktatu

Serlia antycznych rozwiązaniach takich jak tempio w Tivoli, łuki:

Wespazjana, Sewera, Nerwy, Gawiuszy [10].

6

Stosował je także w architekturze świeckiej (dwie elewacje Pa

łacu Luksemburskiego, 1618–1631, fasada Pałacu Parlamentu Bre tanii

w Rennes, 1618).

in 1685) the overloaded decorativeness was used on the

facades, which originated from the Mannerist projects of

this region and was strongly connected with Romanesque

and Gothic patterns.

Reception and interpretations of the Italian method

of facade compositions in Europe

In the next generation, almost all European architects,

who drew from Italian models, arranged decorations of

church facades by means of this method. Usually, while

maintaining a twostorey structure, the facade was divid

ed according to the layout of naves into three fields and

the simplest single pilasters, slightly projecting from the

wall face were introduced (rarely engaged columns or

columns) and emphasized by multiplications. Not only

simple churches of monk orders or parish congregations

in small towns were designed in this way, but also cathe

dral buildings

3

. Doubled supports which derived from the

composition of the church facade Il Gesù were used even

more often than single or perspective multiplied pilas

ters

4

. The evolution of this layout resulted in a clear with

drawal of the central part of the facade with the main por

tal and a large window illuminating the nave or even more

often a strong projection of lateral avantcorpses from the

wall face, which articulated the central part of the facade.

Optically it created the impression of breaking twostorey

porticos and leaving their relics – doubled supports flank

ing the main axis of the facade. Apparently this effect was

manifested by using full artistic forms – strongly projecting

beams on the columns, which gave the facade a new brutal

expression by complementing threedimensional forms

with strongly contrasting chiaroscuro

5

. For the first time

such a solution appeared in a threestorey version in France

in the design by Salomon de Brosse for the facade of Saint

GervaisetSaintProtais Church from 1616–1621

6

.

Fran

çois Mansart used it in a more classic twostorey layout of

3

It is enough to mention the most important – facades – in Italy,

for example, of S. Francesco Saverio, S. Ignazio all’Olivella Churches

in Palermo, the cathedral in Modica, S. Maurizio, S. Domenico in Mar

tina Franca, S. Irena in Lecce, S. Ferdinando and S. Carlo alle Mo r telle

Churches in Naples, S. Agata Cathedral in Galipoli, in Cervo, the Jesuit

church in Venice and in Portugal: Portalegre Cathedral in Coimbra, in

Austria: Barmherzigen Brüder Church in Linz, the Franciscans in

St Poelten, Mariahilf and the Dominicans in Vienna, in the Czech: the

church in Klatovy, in Usti nad Labem, Prague Loreta, in Poland: parish

churches in Poznan, in Lithuania and Ukraine: Jesuit Church in Nie

śwież in northern Europe: Jesuit StFrançoisXavier Church in Bruges,

St Walburga Church in Bruges, and even the Protestant cathedral in

Kalmar and the analogous Fryderyk Church in Karlskrona, or further in

Latin America: the cathedrals in Mexico, Havana, the Fran ciscan and

Jesuit churches in Quito, the Jesuit church in Arequipa.

4

The examples include the Marsala cathedral and Jesuit churches

– in Scicli, Milan, Trapani, Avignon, Antwerp, Louvain, Prague (Saint

Ignatius), Jihlava, Lucerne, Heidelberg, Wrocław, Cracow (St Peter’s

and Paul’s), Vilnius (St Teresa), Lutsk and Lviv.

5

Clearly modelled on the ancient solutions such as tempio in Ti

voli, arches: Vespasian’s, Severus’, Nerva’s, Gavi, which are known

primarily from the treatise of Serlia [10].

6

He also used them in secular architecture (two facades of the

Luxembourg Palace, 1618–1631, the facade of the Brittany Parliament

Palace in Rennes, 1618).