138 Jadwiga Urbanik

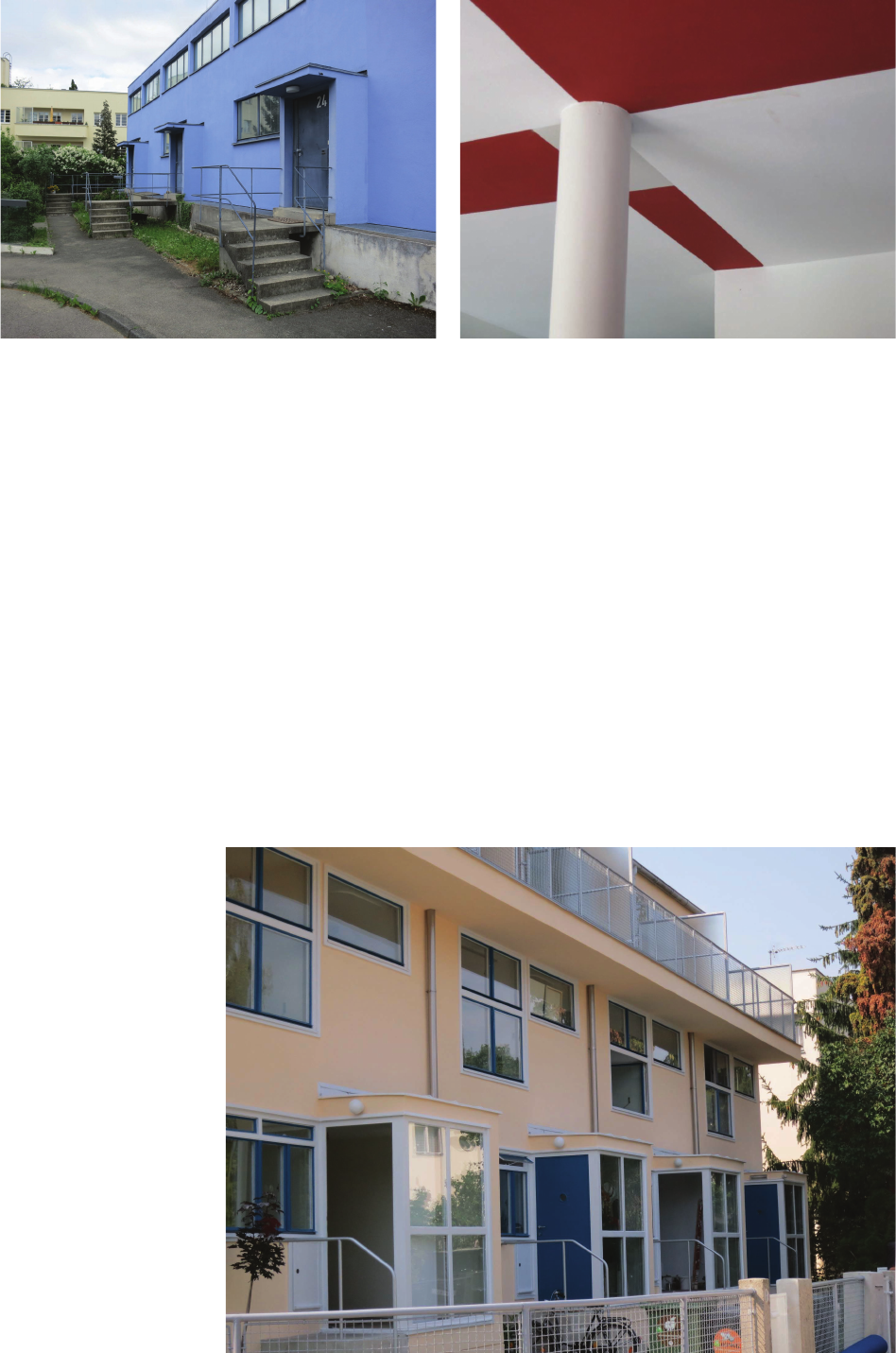

concept even during the execution phase. The façades of

the Ledigenheim building were painted in ochre light (“lu-

minous”) color (Fig. 11). All elements of railings, external

balustrades, window, and door frames were painted in grey

(“mouse grey”). Only the balcony doors of the right wing of

the building were in the color of the elevation – light grey.

The reinforced concrete structure of the trellis on the roof

of the left wing was orange-red concrete (Fig. 12), while

the elements of the building foundation and the retaining

walls were left in their natural color (concrete color).

The general use interiors (lobby and restaurant) fea-

tured strong and vibrant colors. The lobby was a deep blue

color, against which shiny armchairs made of steel pipes

cast silver reections, while the restaurant was dominated

by many shades of red [39, p. 410]. In the saturated colors

of the lobby and restaurant of Hans Scharoun’s house and

in the way they were combined, the spirit of expression-

ism can be sensed. The use of intense colors and simple

geometric patterns (blue and pink stripes on the gable wall

of the restaurant, a blue stripe repeating the shape of the

room on the ceiling of the lobby) is close both to the ex-

pressive shaping of space and to the color tendencies of

the late twenties associated with the German campaign for

color in the city (Fig. 13).

In the residential sections, Scharoun proposed two

color versions in pastel tones (ivory, light ochre, olive

green, ash or ivory, beige, brick red, ash in the right wing

sections), enhanced by wooden or chrome-plated furnish-

ings [27] (Figs. 14, 15).

Hans Scharoun’s house for singles was one of the pro-

jects included in the 1925–1930 nationwide campaign of

the “colorful city” (Die farbige Stadt). In Breslau Hans

Scharoun, Theo Eenberger, Moritz Hadda (architects

of the WuWA exhibition housing estate), and Hermann

Wahlich functioned as heads of departments of the Build-

ing Police responsible for the city’s color scheme [33].

2

nd

half of 1920s was a period of a real “cry for color”,

still originating in expressionism, for which color was

also a means of architectural expression. More than one

million buildings in Germany at that time received a new

coat of color.

It is interesting that the color scheme of the interior of

Le Corbusier’s semi-detached house from the Weissen-

hof estate is almost identical to Scharoun’s proposal from

Wrocław. Although these architects shared a completely

dierent approach to shaping architectural form, their

taste for color was similar. Le Corbusier’s house, white

on the outside, presents a real “cosmos of colors” on the

inside. The colors were saturated, yet fractured, so char-

acteristic of the mineral pigments that were used at the

time (Fig. 16).

Summary

The examples described above show that regardless of

whether they are model houses in the Werkbund housing

estates or houses built as part of the city construction pro-

gram, their colors fall within the trends of “white architec-

ture” or of the “colorful city”. The color scheme clearly

reected the very individual tastes of its architects.

Today, knowledge of the color scheme is essential to

the proper revalorization of interwar architecture, thus

portraying original character is the duty of both historians

and conservators.

Translated by

Jan Urbanik,

proofreading by Katarzyna Jaroch

References

[1] Brenne W., Creating a cosmos of colours. Bruno Taut’s housing

estates in Berlin, [in:] M. Kuipers, E. Claessens, M. Polman, L. Ver-

poest (eds.), Modern Colour Technology. Ideals and Conservation,

Tripiti, Rotterdam 2002, 22–25.

[2] Werkbund Ausstellung “Die Wohnung” 1927, Der Ausstellung-

leitung (Hrsg.), Industrie Verlags- und Druckerei i Werbehilfe,

Stuttgart 1927.

[3] Výstava moderního bydlení Nový Dům Brno 1928, Z. Rossmann,

B. Václavek (red.), Brno 1928.

[4] Werkbund Ausstellung. Wohnung und Werkraum. Breslau 1929. 15.

Juni bis 15. September. Ausstellungs Führer, Ausstellungsleitung

(Hrsg.), Breslau 1929.

[5] Výstava bydlení – stavba osady Baba Praha 1932, P. Janák, L. Sut-

nar (red.), Svaz československého díla, Praha 1932.

[6] Die internationale Werkbundsiedlung Wien 1932, J. Frank (Hrsg.),

Anton Schroll & Co, Wien 1932.

[7] Joedicke J., Weissenhof Siedlung Stuttgart, Karl Krämer Verlag,

Stuttgart 1989.

[8] Kirsch K., Die Weißenhofsiedlung, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stutt -

gart 1999.

[9] Marbach U., Rüegg A., Werkbundsiedlung Neubühl in Zürich-

Wollish ofen 1928–1932, Ihre Entstehung und Erneuerung, Doku-

mente zur Schweizer Architektur, GTA Verlag, Zürich 1990.

[10] Šlapeta V., Urlich P., Křížková A., Great Villas of Prague 6, Baba

Housing Estate 1932–1936, Foibos, Praha 2013.

[11] Urbanik J., WUWA 1929–2019. Wrocławska wystawa Werkbundu,

Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław 2019.

[12] Šenberger T., Šlapeta V., Urlich P., Osada Baba. Plány a modely /

Baba Housing Estate. Plans and Models, Czech Technical Univer-

sity in Prague, Faculty of Architecture, Prague 2000.

[13] Werkbundsiedlung Wien 1932. Ein Manifest des Neuen Wohnens,

A. Nierhaus, E.M. Orosz (Hrsg.), Müry Salzmann Verlags, Wien

2012.

[14] A Way to Modernity. The Werkbund Estates 1927–1932, J. Urbanik

(ed.), Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław 2016.

[15] Brenne W., Bruno Taut. Meister des farbigen Bauens in Berlin,

Verlagshaus Braun, Berlin 2005.

[16] Brenne W., Farbe bei Fassaden des Neues Bauens und der Mo -

der ne, [in:] K. Guttmejer (red.), Kolorystyka zabytkowych elewacji

od średniowiecza do współczesności. Historia i konserwacja, Kra-

jowy Ośrodek Badań i Dokumentacji Zabytków, Warszawa 2010,

225–244.

[17] De Jonge W., Colour and Modern Movement architecture, [in:]

M. Kuipers, E. Claessens, M. Polman, L. Verpoest (eds.), Modern

Colour Technology. Ideals and Conservation, Tripiti, Rotterdam

2002, 8–11.

[18] Hammer I., Lime Cannot be Substituted! Remarks on the History

of the Methods and Materials of Painting and Repairing Historical

Architectural Surfaces, [in:] K. Guttmejer (red.), Kolorystyka za-

bytkowych elewacji od średniowiecza do współczesności. Historia