36 Ewa Węcławowicz-Gyurkovich

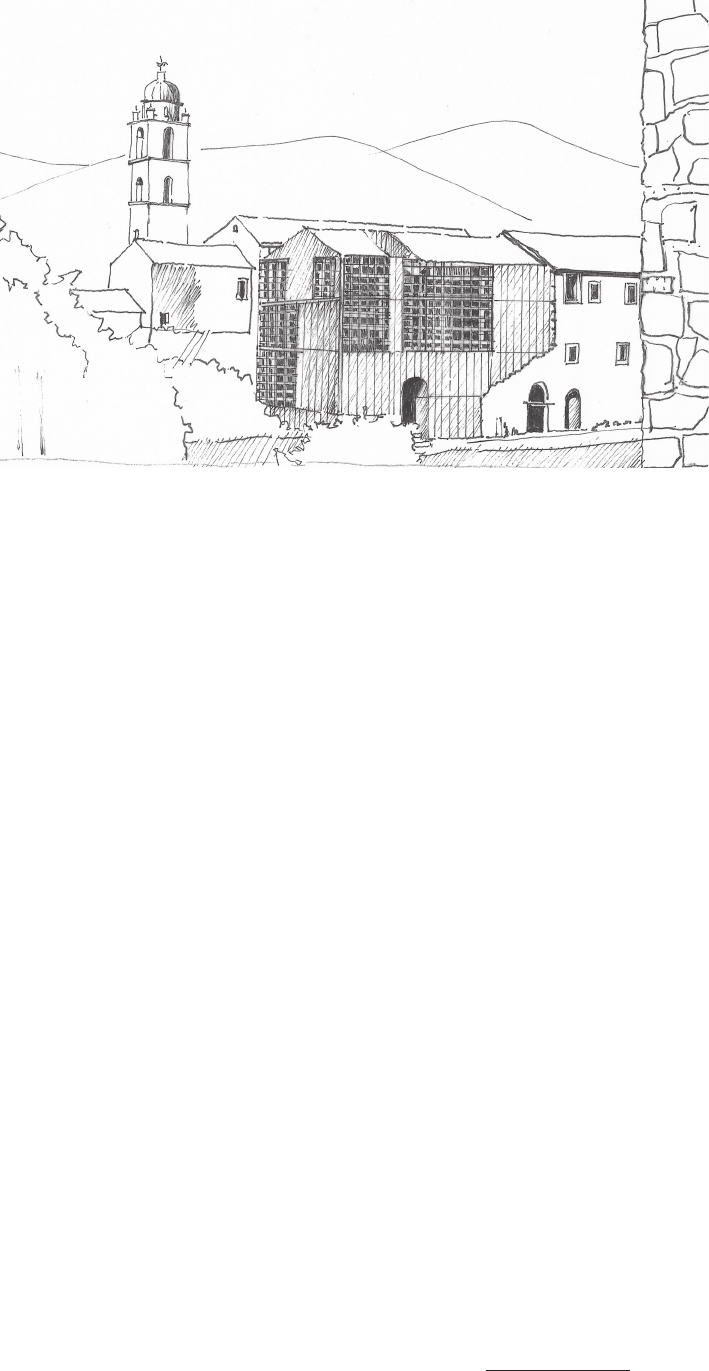

research, which has been carried out for several decades,

is aligned with a trend associated with contemporary ar-

chitectural and urban design in the historical context of

European cities. The coexistence of heritage elements

with new urban, architectural and landscape layouts is

a phe nomenon that is characteristic of early-21

st

-century

European cities. Public buildings with cultural uses and

a scale consistent with the surrounding urban fabric, built

in Madrid, Barcelona, Sainte-Lucie-de-Tallano (Corsica),

Cottbus, Hamburg, Marseilles and Budapest were select-

ed for analysis. These buildings, both new constructions

and adaptive reuse projects targeting historic buildings,

despite their apparent separateness of scale and character,

which depend on their context, are linked by the design

of the aesthetics of their forms and architectural atmo-

spheres, characteristic of New Decorationism, through the

use of external building envelopes with textures created

from clear, repetitive patterns. The selection criteria were

the territorial connement to Western Europe, the period

of construction as the 21

st

century, and the distinctiveness

and diversity of materials used to create the buildings’

decorative envelopes.

About the meanders of thought

In architecture, philosophical and aesthetic concepts

change constantly. Aesthetic concepts are not xed and

unchangeable. In each era, new value criteria and slightly

dierent aesthetics emerge. The concept of beauty has also

changed over the years. Scottish philosopher and historian

David Hume, who lived in the 18

th

century, pointed out in

his works that many people cannot have a proper view of

the concept of beauty because they are incapable of ex-

periencing sophisticated emotions (Eco 2005). Years ago,

a similar question of whether Minimalism makes us hap-

pier than Decorativism was asked by Alain de Botton in

his bestselling book The architecture of happiness (2006).

Artists create their own worlds, which sometimes have

little to do with current reality. Today’s world of aesthetic

exploration in the eld of forms and textures uses other

elds of science such as mathematics, physics, biology,

botany, as well as the latest industrial technologies. Many

contemporary thinkers are of the opinion that the world

of new art, from which architecture stems, is subjected to

a constant process of clashing avant-garde concepts with

the real world, and is dependent on mass media messag-

ing and advertising. Piotr Dehnel is convinced that the ob-

served apparent shallowness and superciality of popular

culture is related to the spread of access to it and is a de-

rivative of the costs we have paid for […] freedom and

justice in civil society. And it is – let us admit it – a price

not too exorbitant compared to the price of human exis-

tence (Dehnel 2006, 292). On the other hand, Gianni Vat-

timo, another Italian philosopher who explored the crisis

and death of art already in the 1980s, warned against the

end of modernity and proposed his own interpretation of

culture, which he called late modernity. He saw evil in

mass culture and the culture widely disseminated by the

mass media, which should be opposed in order not to lead

to the demise of high art. He wrote that aesthetic experi-

ence arises only as the negation of all its traditional and

canonical characteristics, starting with the pleasure of the

beatiful itself (Vattimo 2007). We have known for a long

time that contemporary architecture is tied with painting

and sculpture in the concept of the so-called great reality,

which is based on three principles: rst – every manifes-

tation of reality is worth presenting as per Ruskin’s belief

in “selecting northing, rejecting nothing”; second – every

form of creativity is allowed, and art is to fully reect the

“anarchy of life”; and third – in all external manifestations

of reality we can nd indications of the most internal lay-

ers of nature (Krakowski 1981).

New trends in 21

st

-century architecture

An analysis of recent European projects shows that we

are now seeing a multidirectionality of aesthetic postures.

The rst two decades of the 21

st

century have shown that

new trends and currents in architecture have begun to

emerge. Most of those that emerged in the 20

th

century

have remained, but we can also observe the emergence of

new ones, which are not numerous but are becoming no-

ticeable by their distinctiveness (Węcławowicz-Gyurko-

vich 2014).

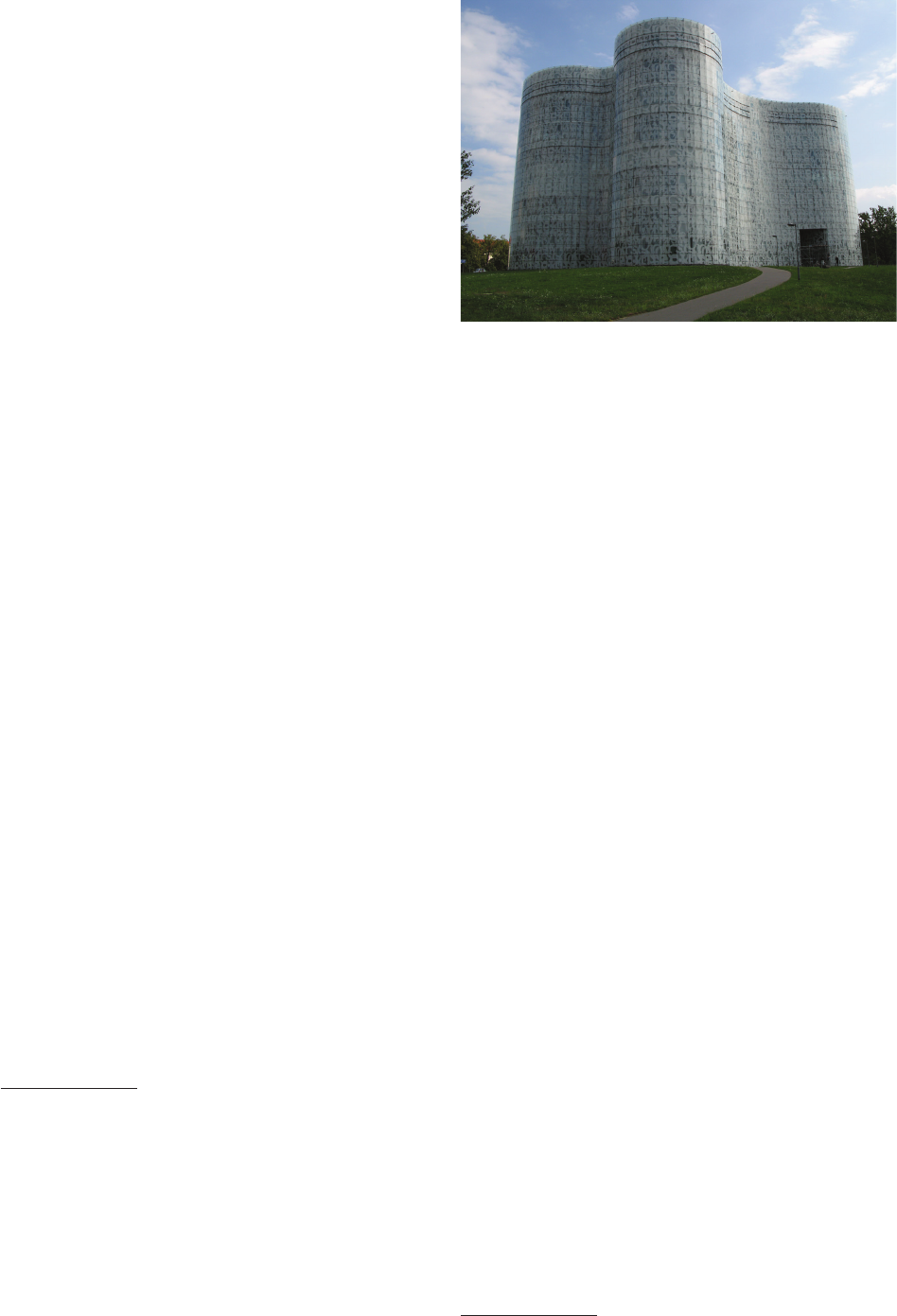

One of the rst to appear was Biomorphism, which ori-

ginated from a virtual architecture that was initially built

only in the digital realm. Biomorphism proposed soft,

rounded forms, often inspired by nature, biology, botany

and even anatomy (Zellner 2000).

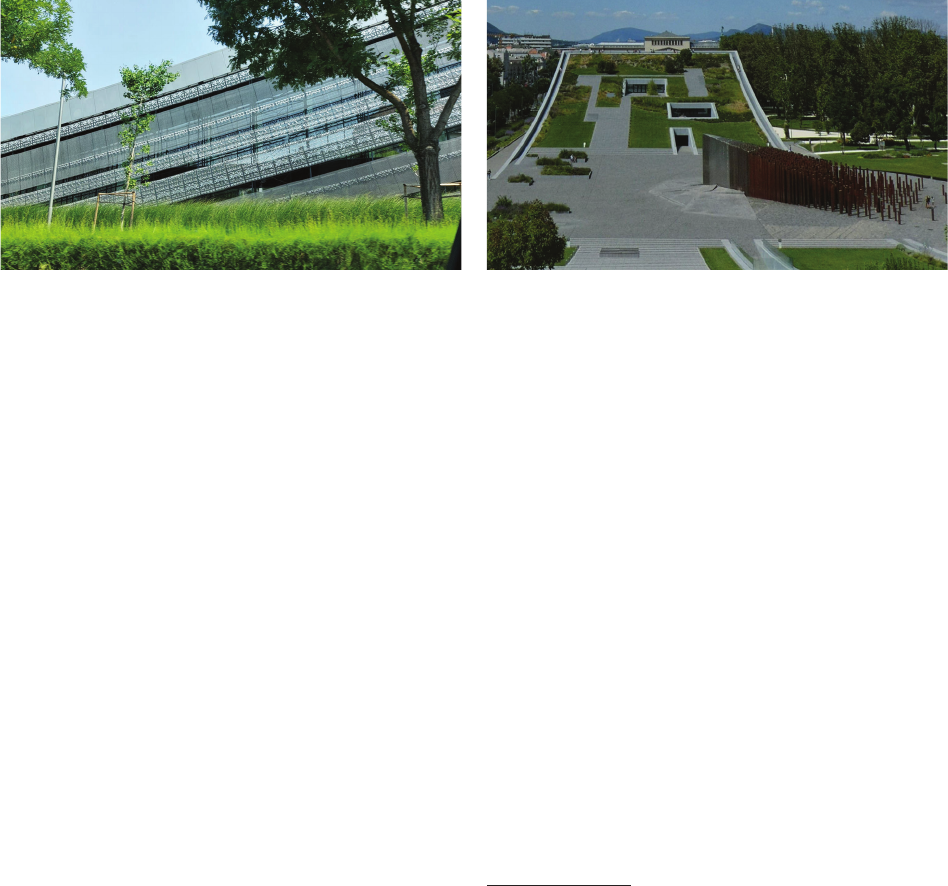

Then we have New Topography, which protects the na-

tural landscape and the uidity of the terrain. Topographic

architecture displays changing events, the motion of pass-

ers-by, and the ow of media images (Nyka 2006). During

the 9

th

Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2004, with the

permission of exhibition commissioner Kurt W. Forster,

this trend was represented by numerous designs and

projects which, by imitating the forces of nature – earth-

quakes, soil delamination, landslides caused by wind and

water – show a landscape that, in its end result, looks as

though it had never been developed by humanity (Meta-

morph 2004).

Another direction is New Expressionism, reminis-

cent of the work of early 20

th

-century architects. In re-

cent years we have also encountered new buildings that

are characterised by dynamism, which achieve an eect

of slenderness, and which depict motion and uidity in

architecture. We encounter buildings with bold, elongated

straight or undulating lines that suddenly become jagged

or are twisted, bent, building forms that are – seemingly

– alien, dierent from those found in the surrounding en-

vironment (Węcławowicz-Gyurkovich 2018).

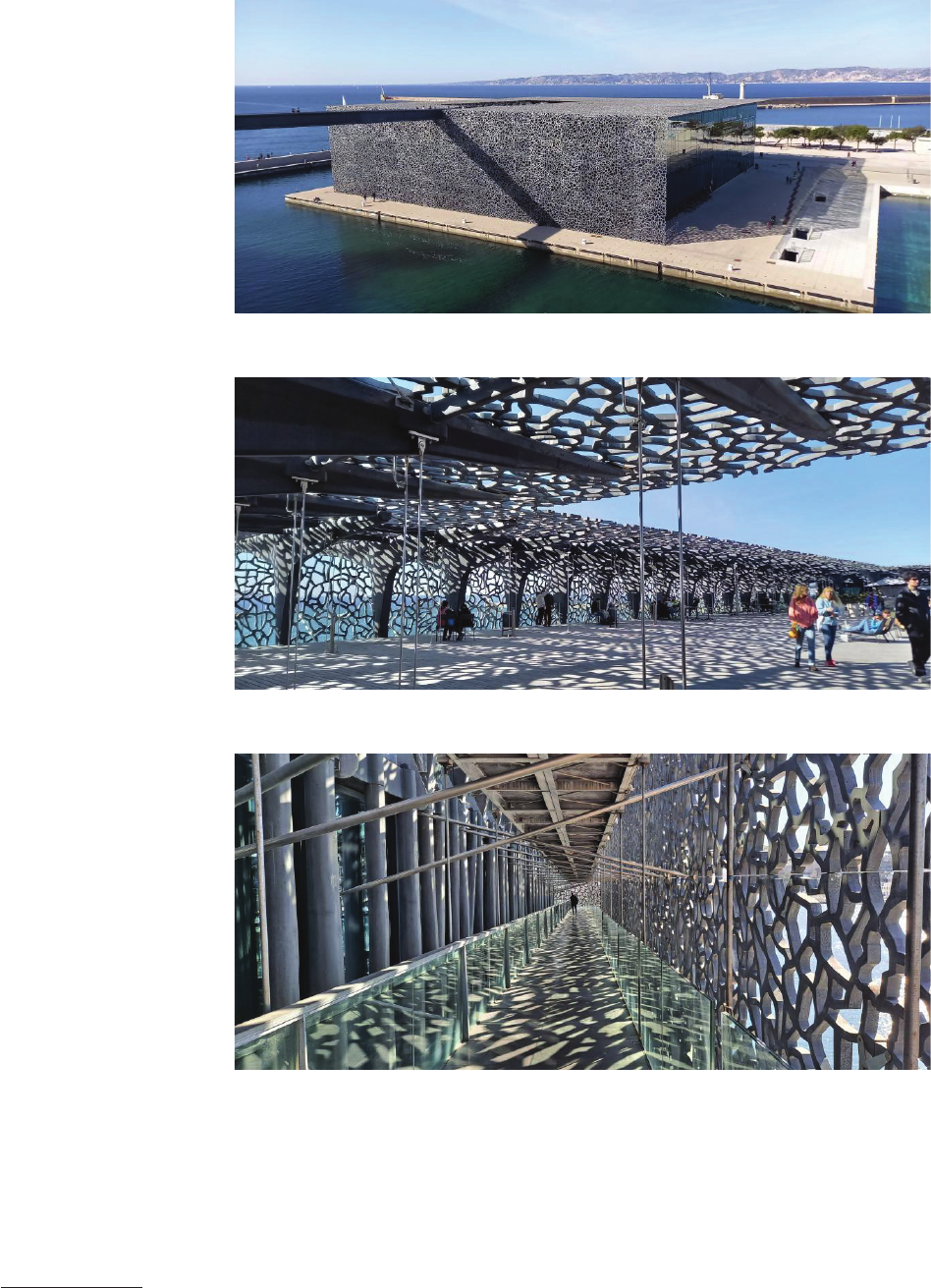

In contrast, one of the most recent trends is New Decora-

tionism. It appears that since the beginning of the 21

st

cen-

tury we have been observing a loss of interest in Minimal-

ism and Reductionalism in architecture, which appeared

in Europe in the 1980s and 90s. This style is understood

as the introduction of decoration and ornamentation into

the external envelopes of new buildings constructed us-

ing various construction materials: metal, glass, concrete,

ceramics, stone or wood. This is most commonly seen in