142 Agnieszka Mańkowska, Artur Zaguła

conrmed by the words of internationally known art, ar-

chitecture and design critic and writer Aaron Betsky, who

in 2016 noticed: Architecture is going pop. It is nally

sloughing o its ridiculous obsession with eternity, and

learning to live in and for the moment. Pop-up architec-

ture, temporary structures, and other ephemeral frame-

works for equally evanescent events have become all the

rage, especially in Europe [5]. In addition, the words of

writer and historian of architecture and design Tom Dyck -

ho, from 2018 also accurately reect contemporary re-

ality: In the twentieth century, […] architecture became

just another form of media, the building “a mechanism of

representation”

1

. The postmodern battle of architectural

styles has been won by the architecture best able to com-

municate in this age of instantaneous global communica-

tion, the one that is the most visible, the most thrilling, the

most protable. Welcome to the Wowhaus [6]. These words

can be an introduction to further research. On a few exam-

ples of temporary architectural structures, the contempo-

rary temporary architecture will be veried in terms of the

possibility of responding to (postmodern) social needs.

Methodology

For the purpose of this article, the authors adopted mul-

tiple case studies as the main research method. Scientic

works assume the recognition of contemporary temporary

architecture in relation to the liquid modernity diagnosed

by Bauman and then an attempt to organize and systema-

tize the selected types of objects in order to collect them

into a typology of postmodern temporary architecture in

terms of the aforementioned philosophy. Hence, in the con-

ducted research, the term “postmodern” in “postmodern

temporary architecture” refers to postmodernity as a uid

modernity, not “postmodernism” as an architectural style.

While the topic of temporary architecture is still a new

and not fully explored issue, there have been attempts to

catalog temporary architecture and the like. It took place,

inter alia, in Rebecca Roke’s book Nanotecture. Tiny Built

Things [7], where the smallest architectural forms have

been divided into the micro, mini, midi, macro and maxi

structures. On the other hand, The New Pavilions [8] by

Philip Jodidio divides dierent kinds of pavilions into

objects for gathering, d’art, learning, displaying, seeing /

listening, living / working / play or shelter. Other works

usually come down to the presentation of selected tempo-

rary objects, which we can see, for instance, in Temporary

Architecture [9] by Lisa Baker or Temporary Architec-

ture Now! [10] by Philip Jodidio. As it was mentioned,

this article’s aim is to formulate a sketch of typology of

all contemporary objects of temporary architecture and

distinguish among them a new category of postmodern

temporary architecture. Due to editorial limitations, the

considerations and conclusions presented in this article

constitute only a fragment of the conducted research. Work

on this topic will be continued in further scientic studies.

1

Colomina B., Privacy and publicity: modern architecture as mass

media, MIT Press, Cambridge 1996 [footnote by T. Dyckho].

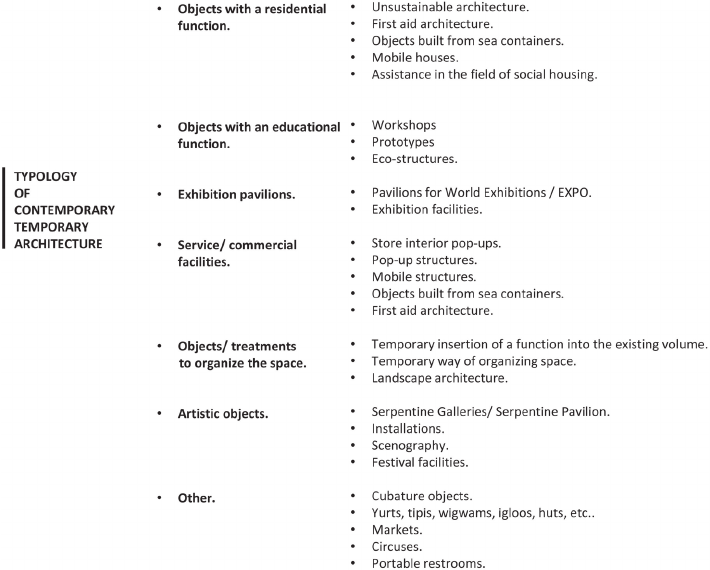

Typology of contemporary temporary architecture

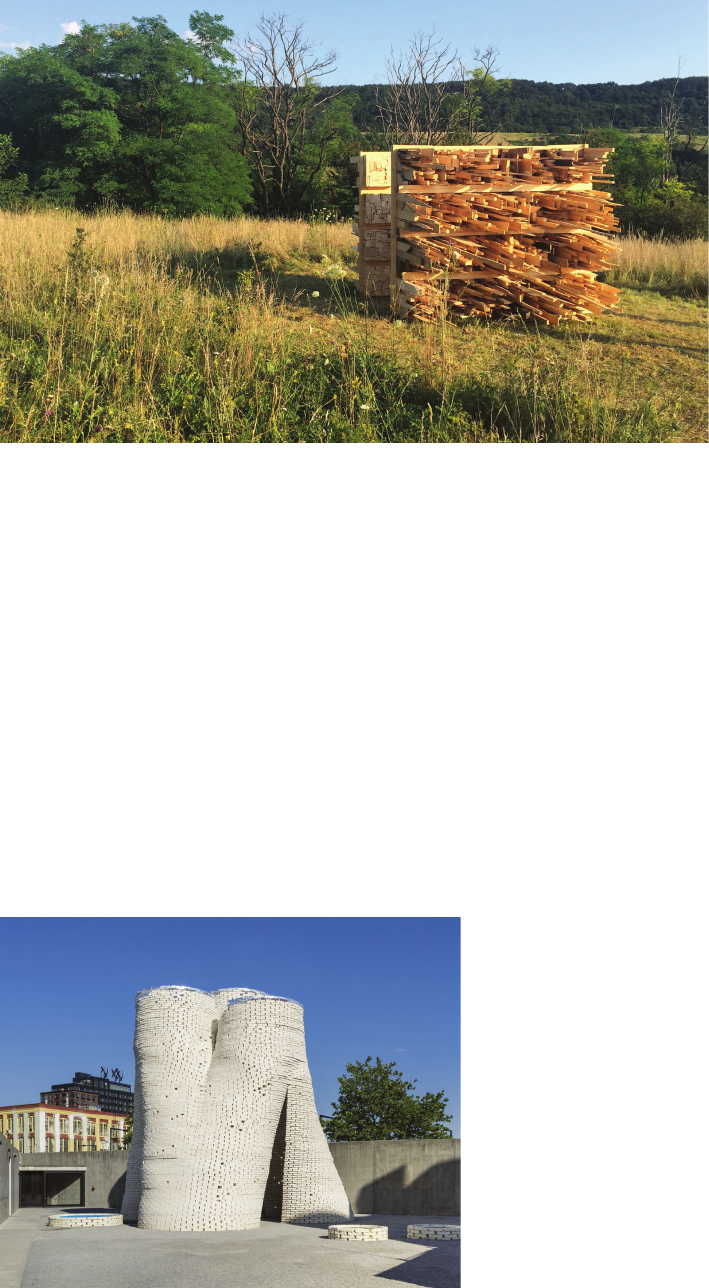

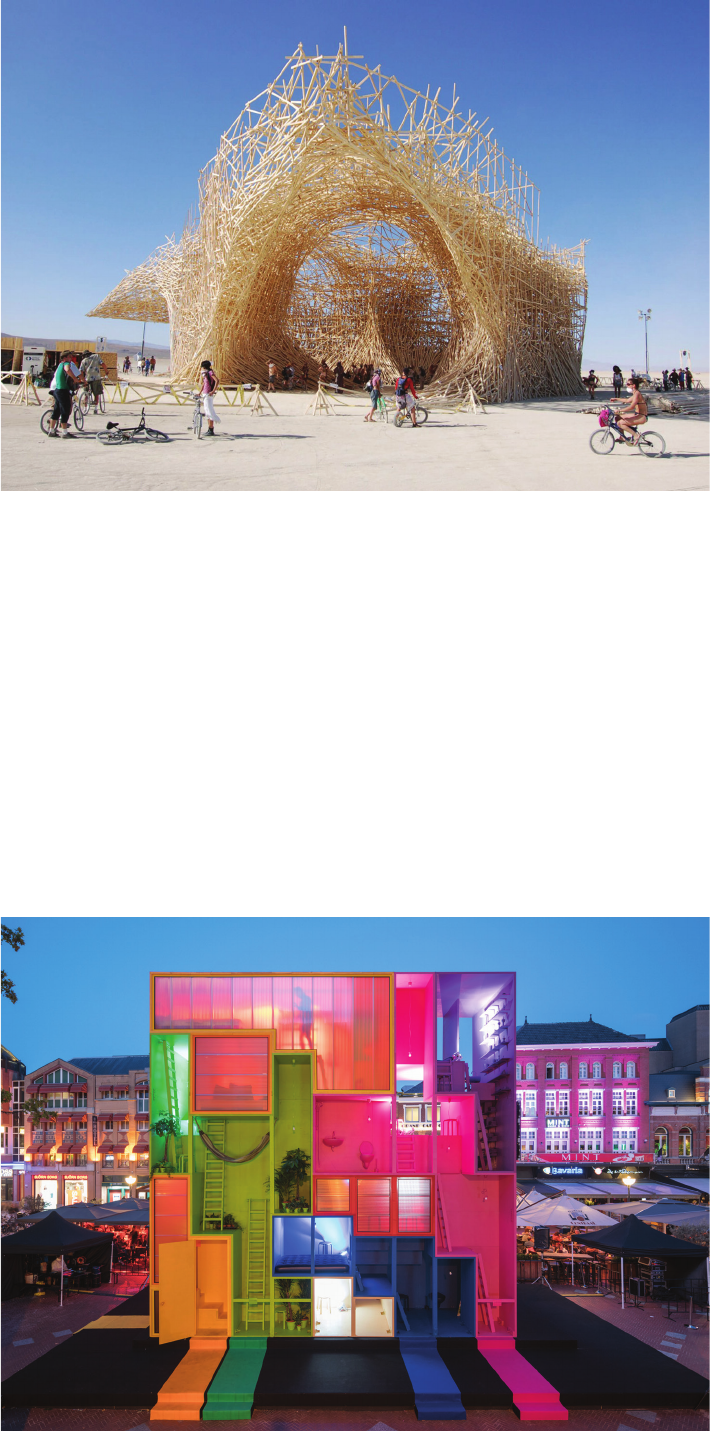

Contemporary temporary architecture is a collection of

objects of dierent nature, function and structure. As they

are architectural objects, they include buildings, struc-

tures and small architecture objects. Their temporary na-

ture is evidenced by the materials used with, for instance,

a limited lifespan; the mobility of elements or the entire

structure; as well as the creator’s conscious assumptions

related to, for instance, obtaining a specic temporary ef-

fect. From a legal point of view, a […] temporary building

structure is a structure intended for temporary use in a pe-

riod shorter than its technical durability, intended to be

moved to another place or demolished, as well as a build-

ing structure not permanently connected to the ground,

such as shooting ranges, street kiosks, pavilions street and

exhibition sales, tent covers and pneumatic coatings, en-

tertainment devices, barracks, container facilities, port -

able free-standing antenna masts

2

[11, p. 3]. On the oth-

er hand, we could even divide temporality in relation to

temporal use, following the work of Ali Cheshmehzan-

gi, who, based on his own considerations also supported

by the research of Tom Mels, William J.V. Neill, Florian

Hayden and Robert Temel, formulated four main types,

including ephemeral, provisional (or interim), temporary

and regular (or regular temporary) [12]. The research of

the authors of this article focused on an attempt to system-

atize contemporary temporary objects due to the function

introduced into them or what function they perform. For

this reason, among all objects of contemporary temporary

architecture, we can nd examples of objects in the fol-

lowing types: objects with a residential function, objects

with educational function, exhibition pavilions, service

and/or commercial facilities, objects and/or treatments to

organize the space, artistic objects and nally other tem-

porary cubatures. Each group will be briey presented and

discussed on the basis of selected examples.

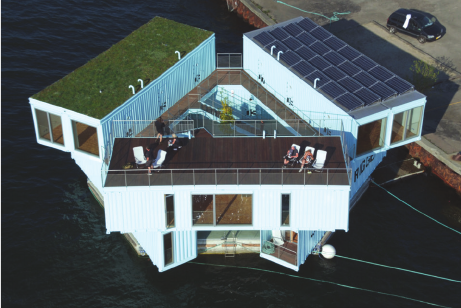

The rst of the above-mentioned types will be the group

of “objects with a residential function” which is a diverse

group, represented both by spontaneously created objects

and well-thought-out constructions, and sometimes even

prototypes. All of the examples show the variety of de-

scribed type, in which we can distinguish, for instance,

objects from unsustainable architecture, structures which

we can dene as “rst aid architecture”, objects built from

sea containers, mobile houses (which, despite possible

controversies, the authors of the article would like to in-

clude as an example of mobile architecture) or assistance

in the eld of social housing.

Starting with favela (favella), as an example of unsus-

tainable architecture, it is a name for Brazilian slums lo-

cated generally in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, as well

as within or outside the country’s other major cities. This

type of development usually arises when wild tenants oc-

cupy empty land on the outskirts of large cities, building

2

The authors emphasize that the quoted record refers to the Polish

Construction Law, in other countries these regulations may appear dif-

ferently or may be unregulated at all.