The architecture of absence. The phenomenon that became a standard 61

References

[1] Ellmann R., James Joyce, Oxford University Press, New York

1982 [Letter to Lucia Joyce (May 29, 1935)].

[2]

Znikanie. Instrukcja obsługi, K. Chmielewska, M. Kwaterko, K. Szre-

der,

B. Świątkowska (red.), Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Warszawa 2009.

[3] Kuczyńska A., Nieobecność jako forma obecności, “Sztuka i Filo-

zoa / Art and Philosophy” 1990, t. 2, 45–56.

[4] Derrida J., Różnia, J. Skoczylas (przekł.), [in:] M.J. Siemek (red.),

Drogi współczesnej lozoi, Czytelnik, Warszawa 1978, 374–411.

[5] Air Architecture. Yves Klein, P. Noever, F. Perrin (eds.), Hatje

Cantz, Los Angeles 2004.

[6] Betsky A., Landscraper. Building with the Land, Thames & Hud-

son, London 2002.

[7] Wines J., Zielona architektura, Taschen, Kolonia 2008.

[8] Sudjic D., Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, James Stirling. New di-

rections in British architecture, Thames & Hudson, London 1988.

[9] Lewis H., Fox S., The Architecture of Philip Johnson, Bulnch,

Boston 2002.

[10] Cecilia F.M., Levene R., El Croquis 104. Dominique Perrault

(1990–2001). The Violence of Neutral, El Croquis, Madrid 2001.

[11] Stefan Müller. Wynurzenia, czyli nic, J. Gromadzka (red.), Muzeum

Architektury, Wrocław 2009.

[12] Głowacki T., Amor vacui. Kilka uwag o architekturze współczes

nej,

“Autoportret. Pismo o Dobrej Przestrzeni” 2007, nr 1 (18), 12–15.

[13]

Landform Building: Architecture’s New Terrain, S. Allen, M. McQuade

(eds.), Lars Müller, Baden 2011.

[14] Ruby I., Ruby A., Groundscapes, Gustavo Gili, Barcelona 2006.

[15] Blasi I., European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture:

Mies van der Rohe Award 2015, Fundació Mies van der Rohe, Bar-

celona 2015.

[16] Cecilia F.M., Levene R., El Croquis 115/116. Foreign Oce Ar-

chitects (1996–2003). Complexity and Consistency, El Croquis,

Madrid 2003.

[17] Folding in Architecture, G. Lynn (ed.), “Ad Prole 102” 1993,

Vol. 63, No. 3–4.

[18] Głowacki T., Szkło w architekturze, „Architektura-Murator” 2014,

nr 02, 94–98.

[19] Translucent Materials. Glass, Plastic, Metals, F. Kaltenbach (ed.),

DETAIL, Munich 2004.

[20] Sarniewicz M., Quantum Glass, czyli szyby produkujące prąd. Pol-

ska rma uruchomiła ich produkcję, “MuratorPlus” 2021, Decem-

ber 20, https://www.muratorplus.pl/technika/instalacje-elektryczne/

quantum-glass-czyli-szyby-produkujace-prad-od-polskiej-firmy

-ml-system-aa-mdSG-iXA7-Fxwp.html [accessed: 22.06.2022].

[21] Bell M., Kim J., Engineered Transparency – The Technical, Visual,

and Spatial Eects of Glass, Princeton Architectural Press, New

York 2009.

[22] Buck P., Pojęcie zmienności w architekturze, PhD Thesis, Wydział

Architektury, Politechnika Wrocławska, Wrocław 2011.

[23] Galindo M., Klanten R., Ehmann S., The New Nomads: Temporary

Spaces and a Life on the Move, Die Gestalten Verlag, EU 2015.

[24] Topham S., Blowup. Inantable Art, Architecture and Design, Pres-

tel, London 2002.

[25] Ruby A., Dusty Relief, [in:] I. Hwang (ed.), Verb Natures, ACTAR,

Barcelona 2006, 148–153.

[26] Rahm P., Philippe Rahm Architectes: Architectural Climates, Lars

Müller, Baden 2019.

[27] Fuery P., The Theory of Absence: Subjectivity, Signication, and

Desire, Greenwood Press, Westport 1995.

[28] Białoszewski M., Rozkurz, PIW, Warszawa 1980.

[29] Baudrillard J., Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?, Sea-

gul Books, London 2009.

[30] Baudrillard J., Towards the Vanishing Point of Art, [in:] S. Lotrin-

ger (ed.), The Conspiracy of Art. Jean Baudrillard, Manifestos, In-

terviews, Essays, Semiotexte, New York 2005, 98–110.

[31] Kitaro N., Last Writings: Nothingness and the Religious World-

view, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1993.

[32]

Kozyra A., Filozoa nicości Nishidy Kitaro, NOZOMI, Warszawa 2007.

[33] Boyarsky N., Metropolis: Institute of Contemporary Arts, London;

4 August–1 October 1988, “AA Files” 1989, No. 18, 80–87.

[34] Szmidt B., Ład przestrzeni, PIW, Warszawa 1981.

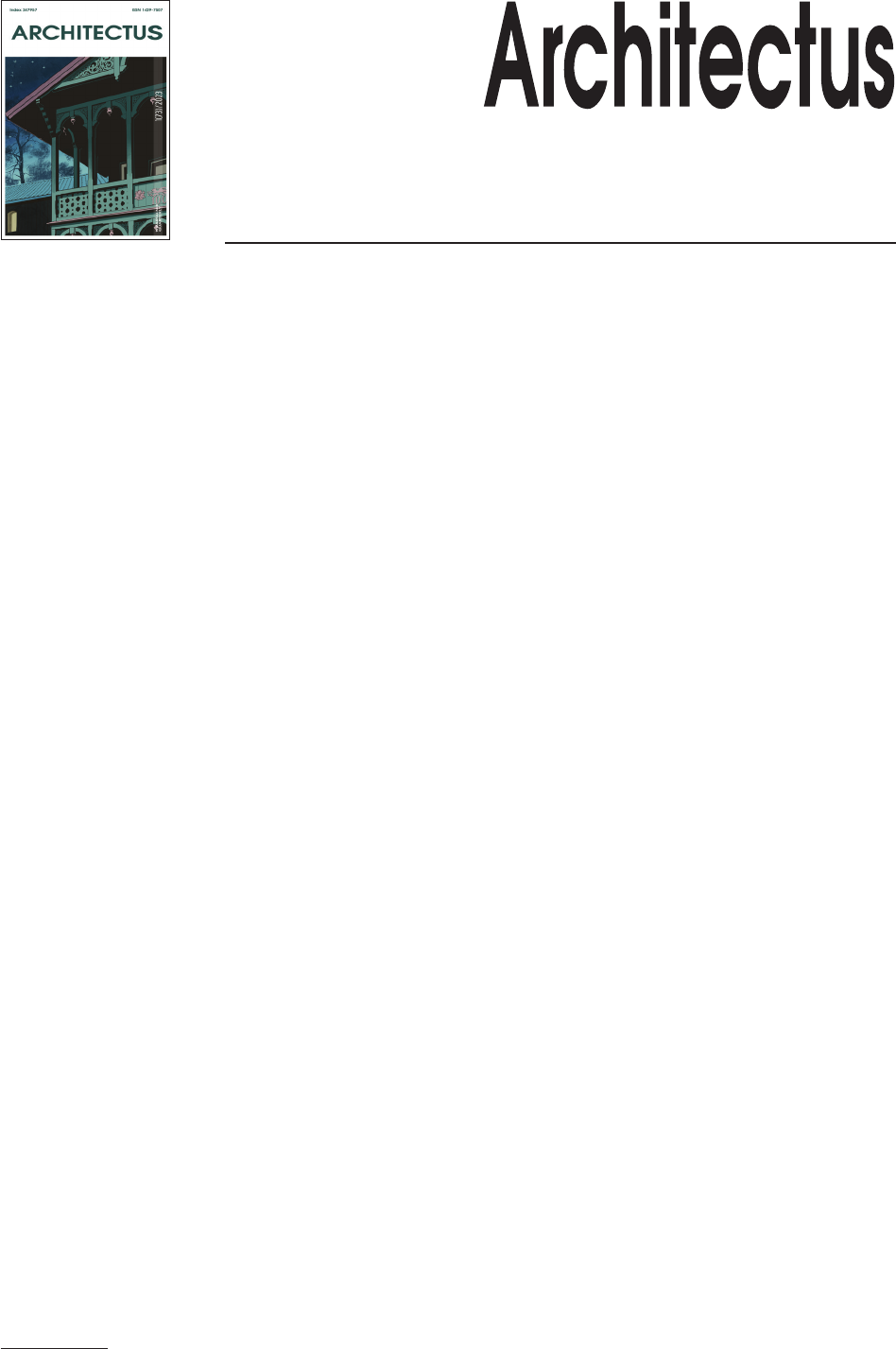

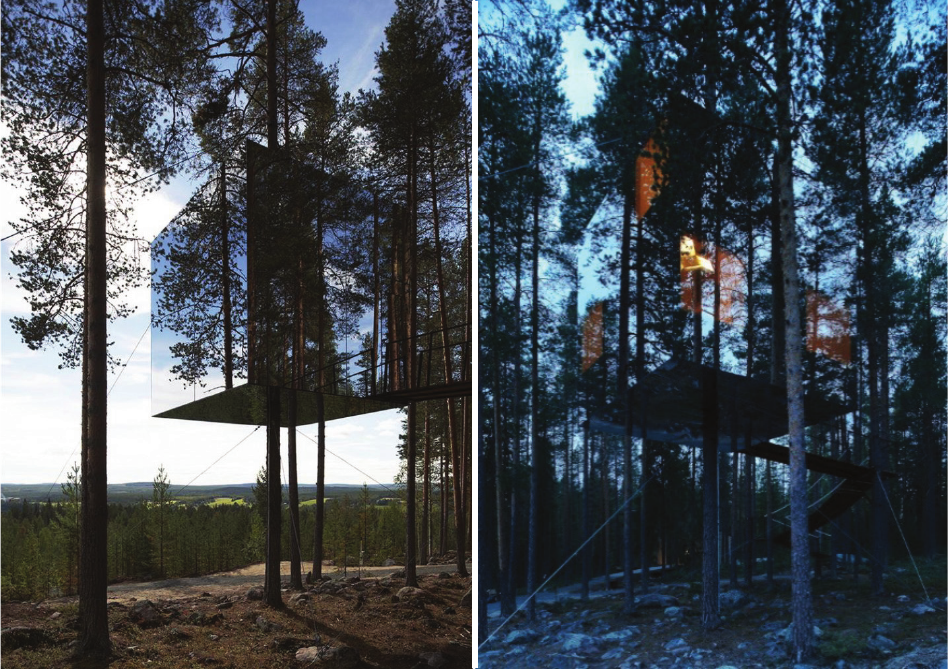

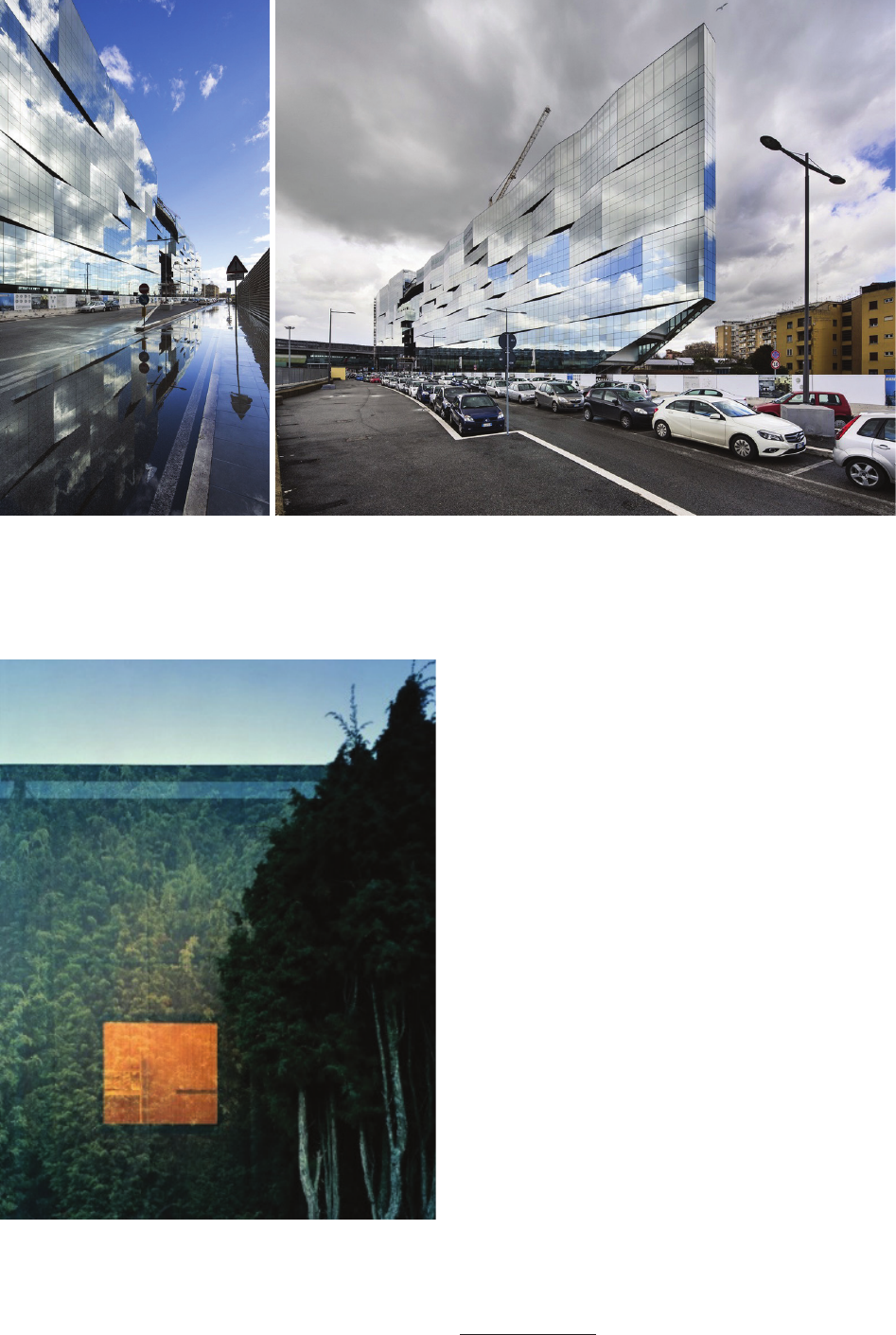

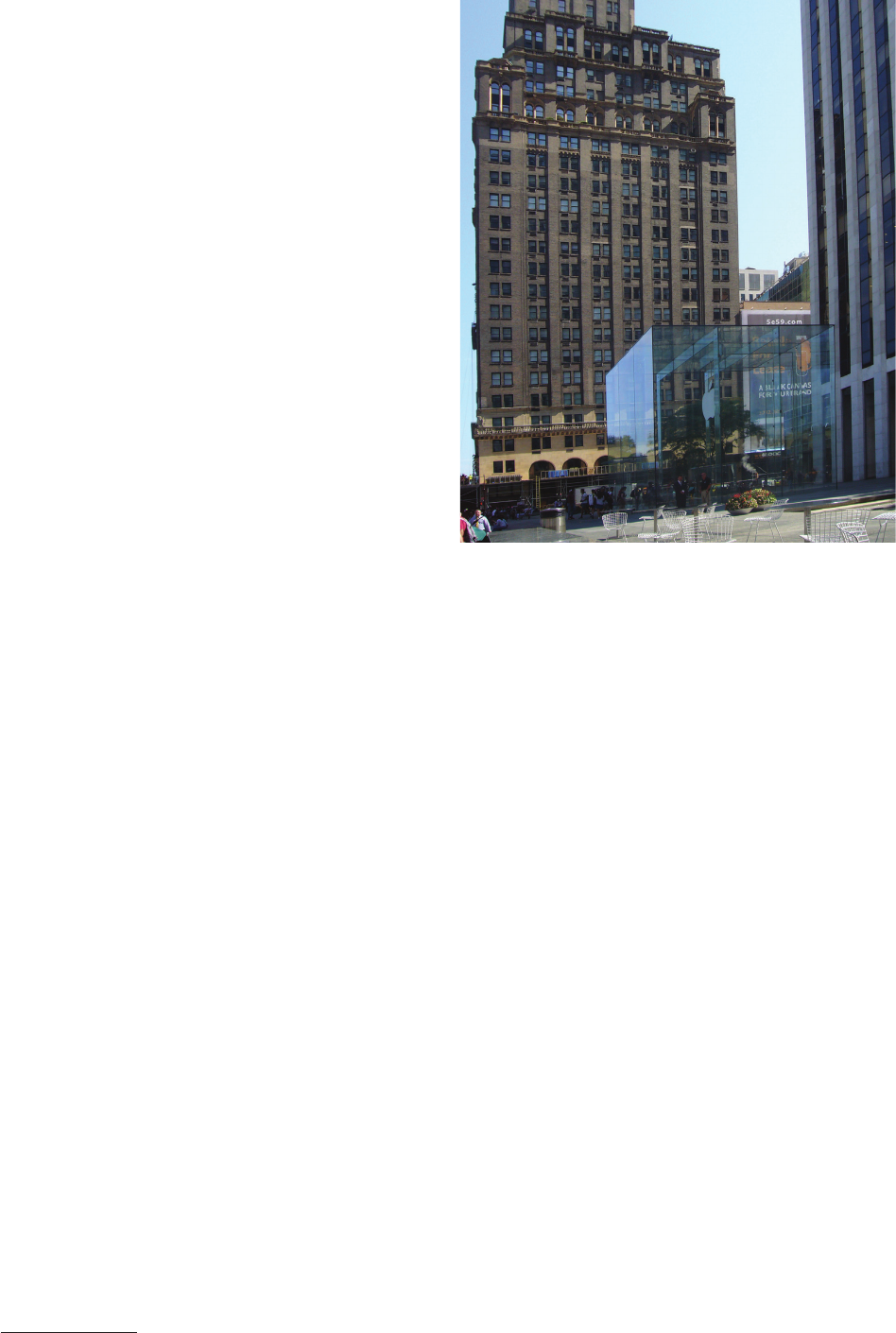

What is important for the studied phenomenon of ab-

sence architecture is the fact that all categories concern

a change in the perception of an object in relation to its

surroundings and context. Architecture ceases to be the

most important element and the protagonist of design ac -

tivities, giving way to space and greenery, the historic con-

text or/and the natural environment. Inextricably linked

with the history of civilization and buildings representing

its development, the need for the building to stand out in

space recedes into the background. Dominance and dis-

tinctiveness in the landscape, characteristic for architec-

ture, the need to exist and to symbolically spin a tale about

the greatness of the investor, architect, god or deity lose

their raison d’être. The undisturbed context and the freed

landscape are becoming the protagonist.

The architecture of absence is a response to the change

in the relationship between the built and undeveloped

environment that is currently taking place. With the ex-

ponential growth of the world’s population, urbanization

and environmental pollution, our planet is being adverse-

ly transformed. From urban centers of civilization amidst

vast wilderness and chemical-free elds, we have trans-

formed the Earth into a densely built-up, concreted and

degraded landscape with only a few islands of natural

greenery. Big industry, agriculture, commerce, urbaniza-

tion and transport have annexed vast areas of land where

nature has been relegated to nature reserves. In such a sit-

uation, when there are fewer and fewer places in the world

undeveloped and devoid of the crowding artefacts of

civilization, the space-releasing architecture of absence,

becomes a psychological and physical need or even, to

quote John Pawson and Claudio Silvestrin, “an absolutely

anthropological necessity” (after: [33, p. 84]).

The architecture of absence emphasizes the role of sur-

roundings and context, its importance and signicance in

maintaining a cubic balance in the designed environment.

It reveals the inseparable relationship between built and

undeveloped areas, and thus between man and nature. It

shows how by withdrawing one’s dominance in space, one

can respect the natural and cultural environment. It tries to

reduce visual interference in the surroundings and nature

to a minimum. It is an answer to the decreasing amount

of space in cities and architectural disorder. It represents

a new way of bringing balance to the built-up world, in

which, as Bolesław Szmidt notes, we have […] fewer and

fewer […] such places on earth, when there is a chance to

see the horizon undisturbed by man [34, p. 252].

Translated by

Anna Zadrożna