18 Ewa Węcławowicz-Gyurkovich

to him and based on Derrida’s philosophy, they laid the

theoretical foundations of deconstruction in architecture.

In the Polish literature, Cezary Wąs [4], Tomasz Ko-

złowski [5] and Anna Krajewska have commented on this

issue: We can therefore say that Deconstruction (whatever it

is – a method, an attitude, a worldview) refers to the notion

of movement. The beauty of Deconstruction certainly does

not lie in stability and normality, but in changeability, mo-

mentariness, unsteadiness of connections [6, pp. 20, 21].

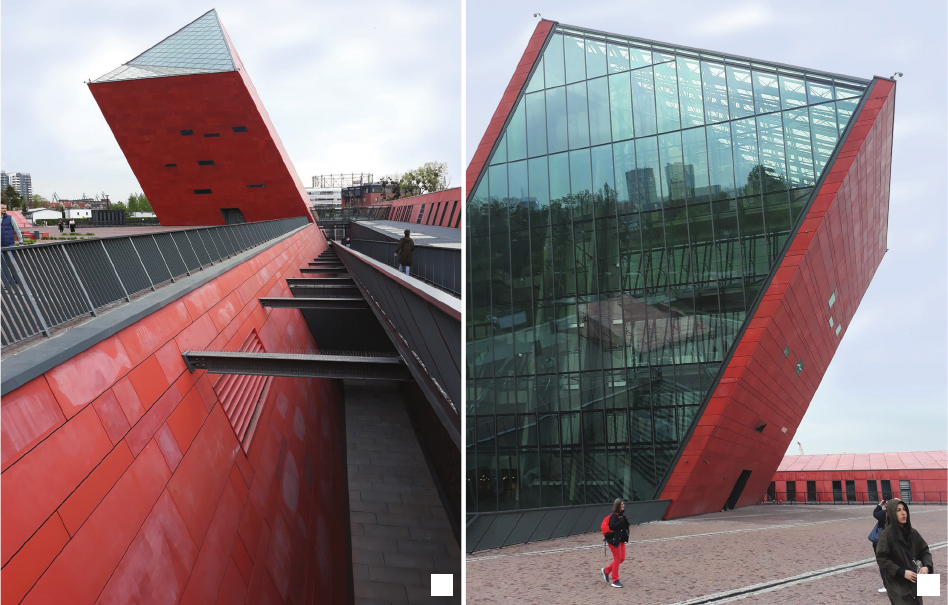

Very often, the nal forms challenged commonly known

principles. In completed architecture, the solids lose their

stability, sometimes giving the impression as if they were

detaching from the ground and ying into space. An im-

portant common element is fragmentation and the intro-

duction of movement, represented by kinetic art, but also

the introduction of the element of time, which occurs in

Futurism – it proclaimed the “beauty of speed”. Curvature,

dislocation, collapse, fracture or squashing, breaking into

parts, explosions, collisions, separations, cutting through

matter and areas evoke shock and amazement. The separa-

tion of function and form became important. This is what

Eisenman wrote in Representations of The Limit; Writing

a “non-architecture”

1

, about the theoretical works and vi-

sual installations of the late 1970s by Daniel Libeskind:

This was the beginning of an attempt to free elements

from their function in both their tectonic and formal sense

– from the causal relationship of function and form (after:

[7, pp. 66, 67]). The provocative confusion and interpene-

tration of forms, which are very often rotated, transformed,

juxtaposed with each other as part of a pre-planned jumble,

do not repeat the familiar compositions of the past. They

are fresh, dramatic, surprising, never seen before. The indi-

vidual buildings are dierent, as they result from each art-

ist’s dierent vision and perception of the world around us.

American architect Mark Wigley’s doctoral thesis

Jacques Derrida and Architecture: the Deconstructive

Possi bilities of Architectural Discourse [8], which was

presented at the University of Auckland in 1986, became

a challenge to organise an exhibition of designs and com-

pleted buildings by seven representatives of this trend at

the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1988. This

exhibition was organised by Philip Johnson and Mark

Wigley. It showcased the designs and buildings of Zaha

Hadid [9, pp. 101–119], Frank Gehry, Bernard Tschumi,

Rem Koolhaas, the Coop Himmelb(l)au team, Peter Eise-

man, Daniel Libeskind. The event reverberated through-

out the world and was followed by numerous magazine

articles. Meanwhile, the book summarising the exhibi-

tion portrayed architecture as a philosophical concept

[10]. Wąs, analysing Wigley’s philosophy, points out that

Deconstruction in architecture is mainly about breaking

down and destroying the structure of forms from within:

This results in the breaking down of the composition, a se-

ries of dislocations, deviations or disruptions […] there

is a discovery of the imperfection consuming the work

1

Eisenman P., Representations of The Limit; Writing a “non-archi-

tecture”, [in:] D. Libeskind, Chamber Works. Architectural Meditations

on themes from Heraclitus, Architectural Association, London 1983.

and bringing the composition to the limits of stability, but

without nally crossing them [4, p. 23].

Published in 1984, Eisenman’s essay The End of the

Classical: The End of the Beginning, the End of the End

criticises the paradigms of value and time in the percep-

tion of architecture. This author writes: […] Architecture

in the present is seen as a process of inventing an articial

past and a present without a future. It remembers a future

that no longer exists (after: [11]). Deconstruction has also

become a language emphasising symbolism and prepar-

ing the viewer to read meanings, even more strongly than

postmodernism. It seems to be more important to inu-

ence the viewer with shape and extravagant massing than

to t into an existing context. The deliberate introduction

of provocation, the creation and search for dierence and,

above all, the freedom to shape forms, emotions and cour-

age against the hitherto existing boredom and schematism

– these are the basic features of the trend.

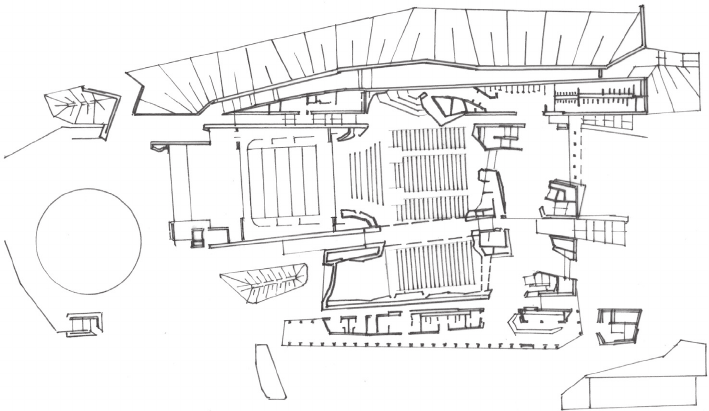

Deconstruction in Poland

In our country, the architecture of Deconstructivism

emerged with a long delay. This was related to the politi-

cal and economic isolation of Central European countries

in the 1970s and 1980s. Economic considerations also

played a major role in delaying the completion of archi-

tecture of this trend here. The inuence of the public level

of preparation for the perception of avant-garde art should

also be emphasised, including the degree of aesthetic ed-

ucation of Polish society, for which the aesthetics of the

late 19

th

century was a model in many cases. Thus, De-

constructivist architecture initially appeared in Poland at

the turn of the 1980s in the form of small-scale structures.

It was not until the second decade of the 21

st

century that

important buildings for culture were created in this style.

Poland in the 1980s was experiencing a social, econom-

ic and political crisis. It seems that during these dicult

years, the inhabitants of our country were preoccupied

with satisfying their subsistence needs rather than intro-

ducing avant-garde aesthetics. This delay was mainly due

to the economic situation of the country and the investors,

as well as the lack of access to the latest technologies and

building materials that the Deconstructivist realisations re-

quired. It is a very elitist movement, with very few build-

ings completed in Europe and around the world. In Poland,

experimental examples of this trend began to appear in the

late 1980s and early 1990s in interiors, mainly of public

buildings. At that time, it did not require large nancial

outlays. Today, many of these interiors no longer exist. In

2001, a multi-family, four-storey residential building was

completed in Krakow at 32 Wybickiego Street [12, p. 179].

In this case only a twisting of the front wall on the side of

Józefa Wybickiego Street was applied. In the architect’s

opinion, this building cannot be qualied in its entirety as

a realisation in the Deconstructivist trend

2

. Such delicate

2

The building was designed by Elżbieta Kierska-Łukaszewska,

and in researching Krakow’s late 20

th

and early 21

st

-century architecture,

Maciej Motak classied the building as deconstruction [12, p. 179].