The Modern Movement in the sacred architecture of Wrocław between 1912 and 1933 27

occasions proved to be the driving force behind changes

in the perception of architecture as an elementary part of

celebration, where by its very nature the liturgy in ceremo-

nial form was not the starting point, contrary to the Cath-

olic milieu [24, pp. 119–127]. Protestant churches showed

a somewhat greater openness to modern forms of expres-

sion; nevertheless, as in the Catholic milieu, attachment

to tradition still halted for a long-time radical changes in

the shaping of the form of modern sacred architecture in

dialogue with the modernizing world. Both Catholics and

Protestants, in attempting to redene the place and charac-

ter of the Church in the modern world, consequently also

had to face the question of what character the building ex-

pressing this place would take on. In this context, many

young architects seized the opportunity to experiment with

modern forms also in sacred architecture, even if the only

form of expression were to be conceptual designs. Rudolf

Schwarz, Dominikus Böhm and Otto Bartning belonged to

this group. Their innovative concepts balancing between

minimalism, functionalism, and expressionist tendencies

aimed to construct a modern form that on the one hand tran-

scended tradition and on the other hand was appropriate to

the mystical character of the church as a place of worship.

Against this backdrop, Wrocław presents itself as a re -

ligiously heterogeneous city, a lively cultural center, which

in the 1

st

decade of the 20

th

century found itself on the

threshold of its greatest historical development – also on

the artistic level. The decline of the empire, the Great War,

the forcoming of the Weimar Republic and thus the new

political order, as well as the overpopulation crisis, placed

the city in a completely new reality.

Max Berg’s designs from 1912–1922

Among the many consequences of Wrocław’s radical de-

mographic development was the need for adequate burial

space and cemetery infrastructure. From Wrocław’s ne-

cropolises, the Grabiszyński and Osobowicki Cemeteries

were the fastest growing, so it was there that new invest-

ments were sought. The rst of these is the concept, or

rather a series of designs for a crematorium for the Gra-

biszyn Cemetery by Max Berg.

The history of the plans for a crematorium for Wrocław

begins as early as 1911, when the Wrocław City Council

de cided to build a new burial complex in the Grabiszyń-

ski Cemetery, consisting of a crematorium with facilities,

a chapel, and an extensive columbarium [25, p. 1], [8, p. 408].

Max Berg, being the acting Municipal Building Coun-

cillor, did not take the opportunity to commission a specic

architect, nor did he launch a competition, but personal-

ly undertook the work on the disposition of the Municipal

Council. As a result, over the course of a decade, sever-

al concepts emerged, illustrating the evolution of Berg’s

style and artistic preferences [26, p. 442]. Amongst the

most original versions dating back to as early as 1912,

strong inuences from Byzantine architecture are discern-

ible (which is particularly evident in the idea of a central

composition of a single or multi-dome building, together

with its variants), as well as ancient architecture of the

East – especially the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and the

spiral minaret of the great mosque in Samarra, fragments

of which were discovered in 1911. These motifs can be

seen both in sketches from the Deutsches Museum in Mu

-

nich and in later designs. Berg returns to them repeatedly,

constantly modifying them. This can be seen both in the

cross-sections of a design that Berg made in collabora-

tion with Albert Kempter in October 1912, preserved in

the collection of the Institut für Regionalentwicklung und

Strukturplanung in Erkner, near Berlin, under the invento-

ry number N193/68 [8, p. 420] as well as one of the last,

which he also executed in collaboration with Kempter be-

tween 1920 and 1921. From the point of view of the gene-

sis of Berg’s style, it is interesting to compare his concept

with the crematorium in Dresden, discovered a few months

earlier, by Fritz Schumacher. The inuence of the so-called

“Zyklopenstil” – a term coined by Karl Scheer for the

synthesis of monumental Wilhelminian German architec-

ture of the 1

st

decade of the 20

th

century [27, p. 100] – is

evident in Berg’s concepts, as well as in the Schumacher

crematorium mentioned above.

The creative use of historical forms, while at the same

time searching for an adequate contemporary form is a fre-

quent phenomenon in the period of nascent modernism

– as Matthias Schirren points out [28] – it is one of the fun-

damental features of the work of Hans Poelzig, who drew

extensively on the formal and structural resources of Goth-

ic or the motifs of indigenous architecture, including tim-

bered construction. As it turns out, this phenomenon was

also not foreign to Schumacher (mentioned above) and

above all, Berg. Berg modied the design many times, but

it can be said that in general, all versions share a common

ideological direction – a centrally located chapel – clear-

ly dominating the cemetery space – topped with a dome

and surrounded by a cloistered columbarium, composed

in a variety of dierent variants. Even a cursory review of

crematorium buildings built in the German-speaking area

around 1910 reveals certain analogies. In addition to the

already mentioned Dresden crematorium, a central struc-

ture with a chapel or conagration hall topped by a dome

and surrounded by cloistered columbariums, the Sihlfeld

crematorium in Zürich, designed by Albert Froelich, is an

intriguing structure.

Berg’s concept for the crematorium, as envisaged in the

original design of 1912, was to consist of a tall, but some-

what squat chapel, designed on a square ground plan, with

much lower, oblong columbariums added on the sides.

The chapel was to be crowned by a stepped dome with

a lantern. As the troublesome part of the complex, the cre-

matorium was placed in the basement, while the chimney

was situated at the back of the building, invisible from the

front, where it was to be dominated by a column portico

with a monumental staircase.

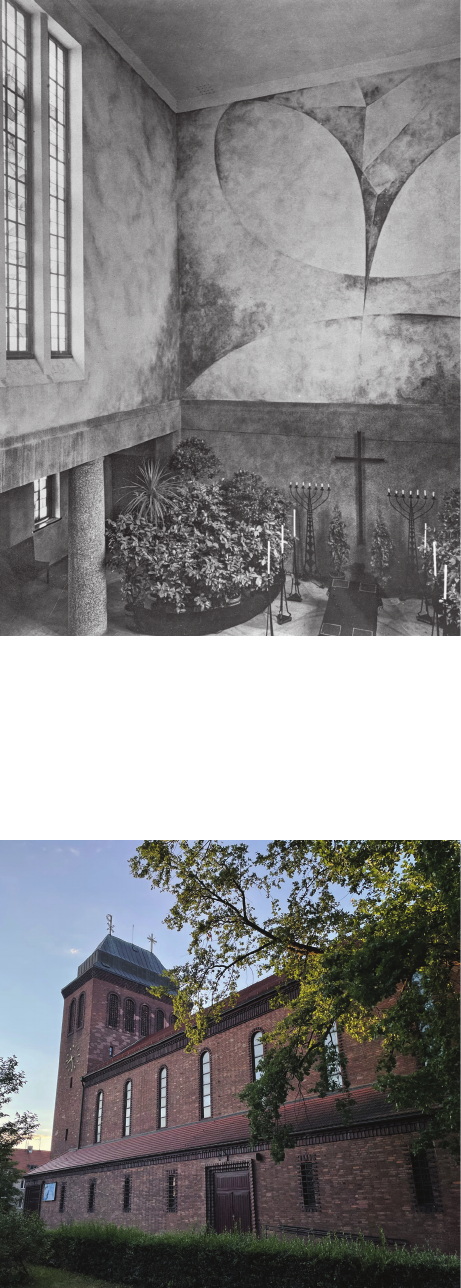

As the visionary, Berg was fully aware of the impor-

tance of the complementarity of the arts, so he invited

the Austrian Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka to

collaborate on the concept of the crematorium, as he had

done with Centennial Hall, this time oering him the op-

portunity to create a monumental painting with eschato-

logical themes for the interior of the crematorium chapel

[8, pp. 408, 409]. Kokoschka was tasked with completely