78 Sebastian Wróblewski

cal solutions with modernity as it was implemented in the

historic district of Beirut. The three capital cities: War-

saw, Berlin and Beirut have dierent approaches to the

19

th

– early 20

th

century reconstructions due to the varia-

ble factors. In each example, valuable experiences could

be derived in future. Of course economic, social, polit-

ical and even religious factors are important and in the

case of each city and those factors were analysed in many

forms and in a variety of scientic and popular articles.

But usually the factor of aesthetic quality or tting into

the local context of architecture was hardly mentioned. As

it was put in the Riham Nady quoted book Historic Cities

and Sacred Sites. Cultural Roots for Urban Futures

2

: The

regeneration of historic centres is not a luxury. However,

it is a part of a collective obligation to understand and

preserve history, tradition and cultural diversity to combat

a sense of transience and to attract tourists [8]. The ques-

tion of why not only the local inhabitants of the city for

whom the reconstruction is important for national or local

identity, tradition, history but also tourists gather in large

number in historic – the 19

th

century style areas and not

in Modernist or contemporary districts of historic cities

(even when those included “iconic” architecture), might

be explained, as one of the greatest contemporary philos-

ophers – Roger Scruton said – by a pursuit of Beauty [9].

The 19

th

century became in contemporary society associ-

ated with the epoch of elegance and beauty in architecture

and generally in cultural landscape of that age. Especially

Belle Epoque or Art Déco – times before the Great War

or from the interwar period – has become an archetype of

such image, and in the case of Beirut both periods con-

tributed much to the landscape of the city. The 19

th

cen-

tury architecture – even neglected, forgotten, covered in

patina or ruined might be perceived by people as more

beautiful, interesting, more “romantic” than “original”

contemporary Modernist architecture in the same state of

deterioration. Therefore a lot of the preserved 19

th

cen-

tury architecture is facing a period of revitalisation now,

and the original 19

th

century districts became fashionable

in dierent European (or European cultural circle) cities

(Kreuzberg in Berlin, Praga district in Warsaw). That’s

why since the 1990s many large scale reconstructions or

renovations of the 19

th

century districts and single build-

ings have been continued. The renovated or reconstructed

areas are becoming not only ourishing city spaces for the

inhabitants but also a sought after destination for tourists.

In Berlin most of the historical centre of the German

capital was reconstructed after the Unication of Ger-

many according to the 19

th

century urban plan with full

reconstruction of only a small number of individual archi-

tectural objects or their façades from the 19

th

century

which were reconstructed (including Alte Kommandan-

tur 2003 and at present the palace of the Prussian kings’

Stadtschloss – both these projects are not full reconstruc-

tions – some of the back or side façades are modern with

only rhythm of windows adopted to pre-20

th

century com-

2

Edited by Ismail Serageldin, Ephim Shluger and Joan Martin

Brown, World Bank Publications, [n.p.] 2001.

position) [10], [11]. Nowadays projects focus on recon-

structing the urban layout lled with new architecture

respecting only some of the layouts of the 19

th

-century

town planning such as development lines, subdivision,

solids with storeys, and to a lesser extent the composition

and colours of façades of tenement houses (Unter der Lin-

den and Gendarmenmarkt areas). Rhythm of façades and

scale are quite similar to the late 19

th

century solutions.

Detail is modern or reduced. Materials are basically tradi-

tional yet not exactly copied from previously used in his-

toric façades. Although some fully reconstructed façades

are also designed and placed in between the modern tene-

ment houses, the number of such designs is limited.

In Warsaw the historic Old Town was reconstructed

since the end of the World War II and followed conserva-

tion rules. Exact lines of frontages, reconstructed narrow

plots based on historical research of the pre-19

th

centu-

ry landscape of the city were brought backing Old Town

and New Town districts of Medieval origin. Designs of

every tenement house were given to teams of artists,

architects and builders. The details were carefully studied

and new decorations in cases where it was impossible to

fully reconstruct the original look were introduced (new

wall paintings, sgratos etc.). Reconstruction works of

the Medieval district were appreciated by the UNESCO

and the Old Town was placed on the World Heritage List

in 1980. Of course during the reconstruction of the dis-

trict according to the vision based on 18

th

century vedute

by painter Canaletto, some mistakes were made – e.g.,

destruction of the late 19

th

century architecture (which in

the mid1950s was not regarded as historical monument).

However, the rest of the capital landscape, shaped in the

19

th

century was not that fully reconstructed. The close

surroundings of the Old Town with the main axis–Streets:

Krakowskie Przedmieście and Nowy Świat which were

shaped before the 19

th

century as a main Royal way to the

city, were reconstructed also according to the 18

th

century

paintings, but the rest of public spaces organised in the fol-

lowing centuries were not, only some important architec-

ture was reconstructed, e.g. churches, National Opera, few

tenement houses which were partially destroyed during

World War II. First attempt to ll in the gaps and recon-

struct both the spatial plan or architecture from the 19

th

cen-

tury started after Poland became fully independent in the

early 1990s. The major works started in few areas such as

Theatre Square and Trzech Krzyży and Bankowy

Squares,

also there is a plan to reconstruct Piłsudski Square. In all

those city public spaces usually the 19

th

cen tury

palaces

(the Jabłonowski Palace or in the future the Saski Pal-

ace at Piłsudski Square) were or will be reconstructed in

historical design. The tenement houses were replaced by

modern designs (but there is a possible plan to reconstruct

a frontage at Piłsudski Square with historical façades of

tenement houses) but shaped according to the conserva-

tory rules in terms of scale, rhythm and composition of

façades, vertical shapes of windows etc.

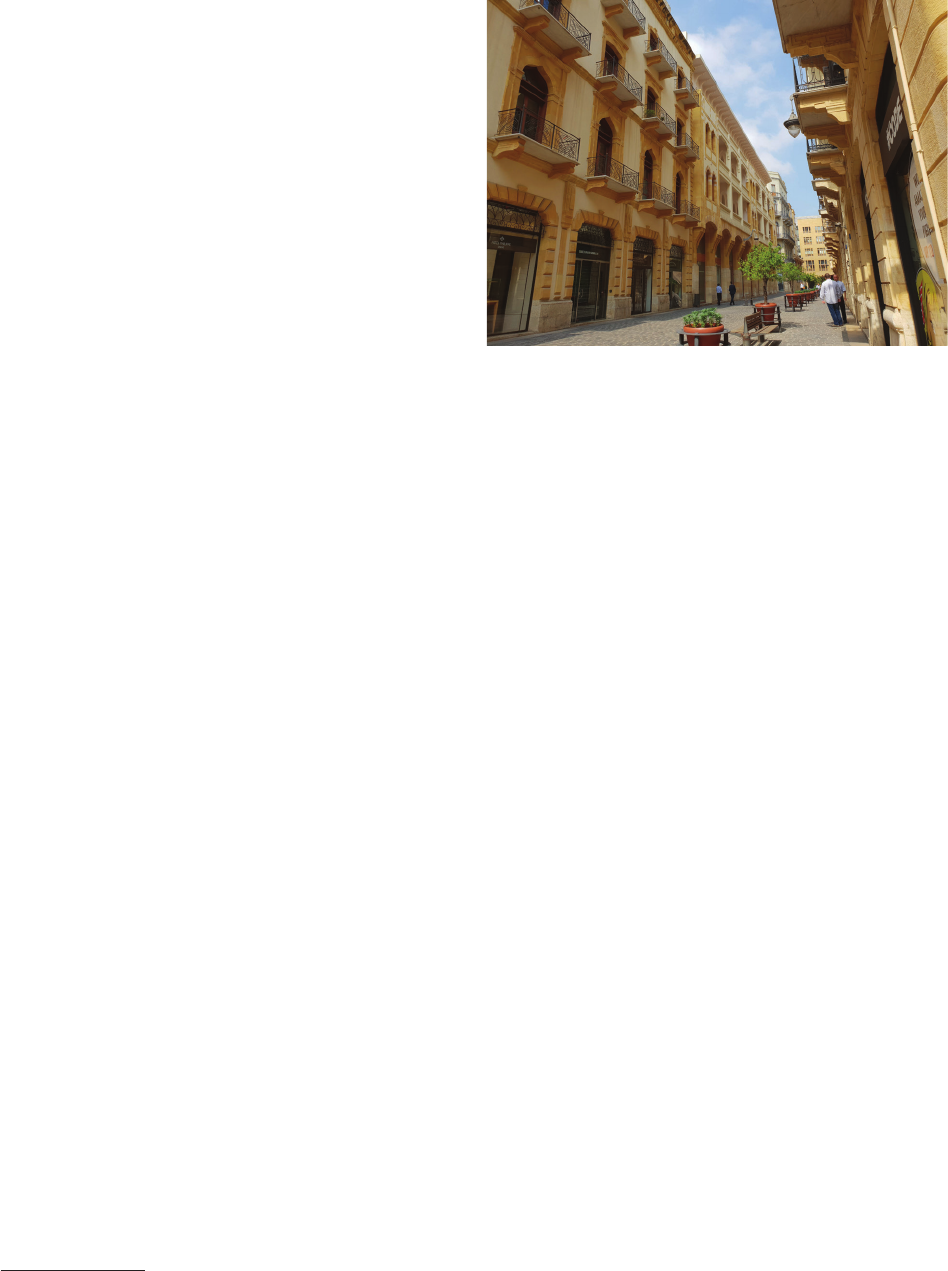

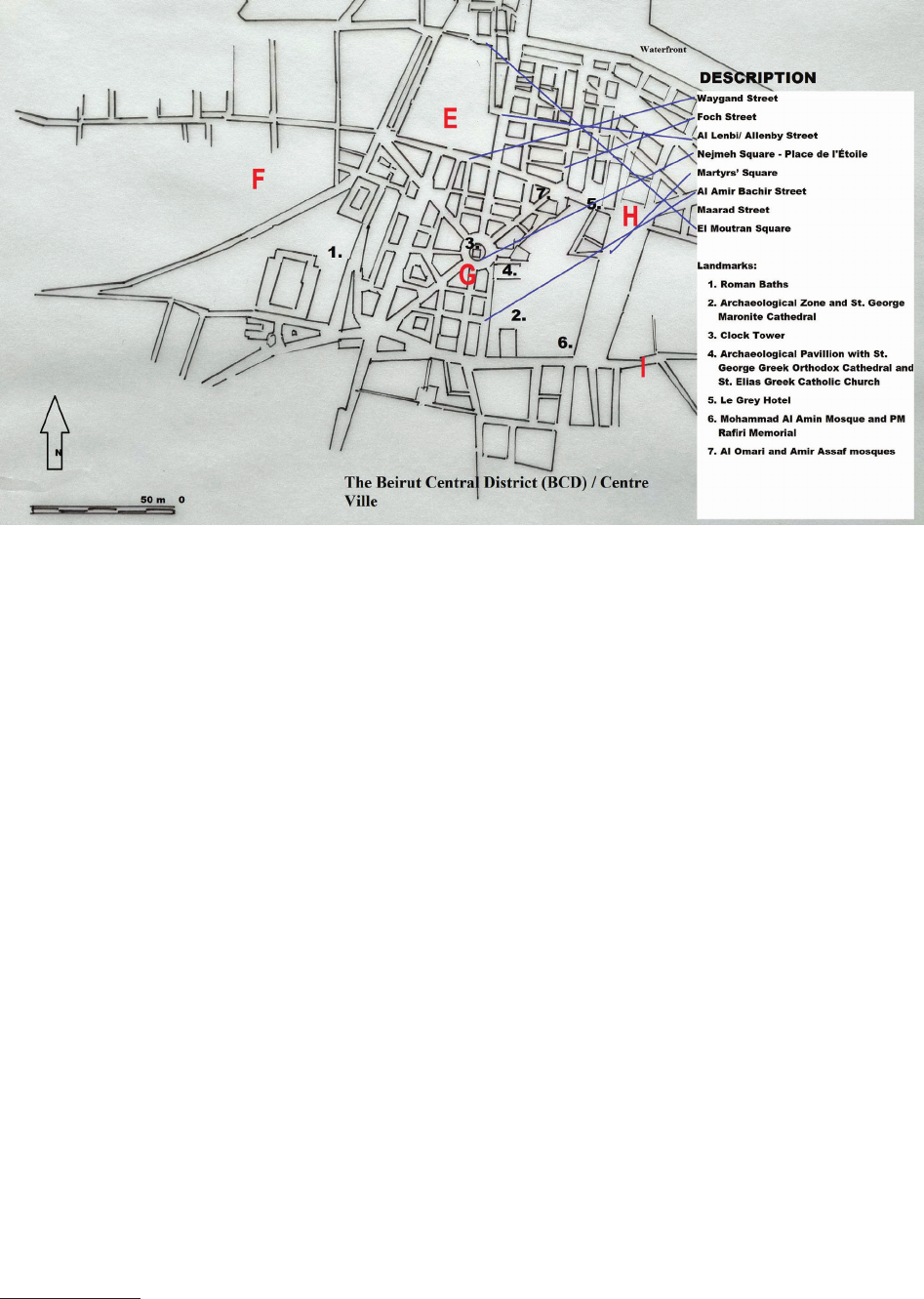

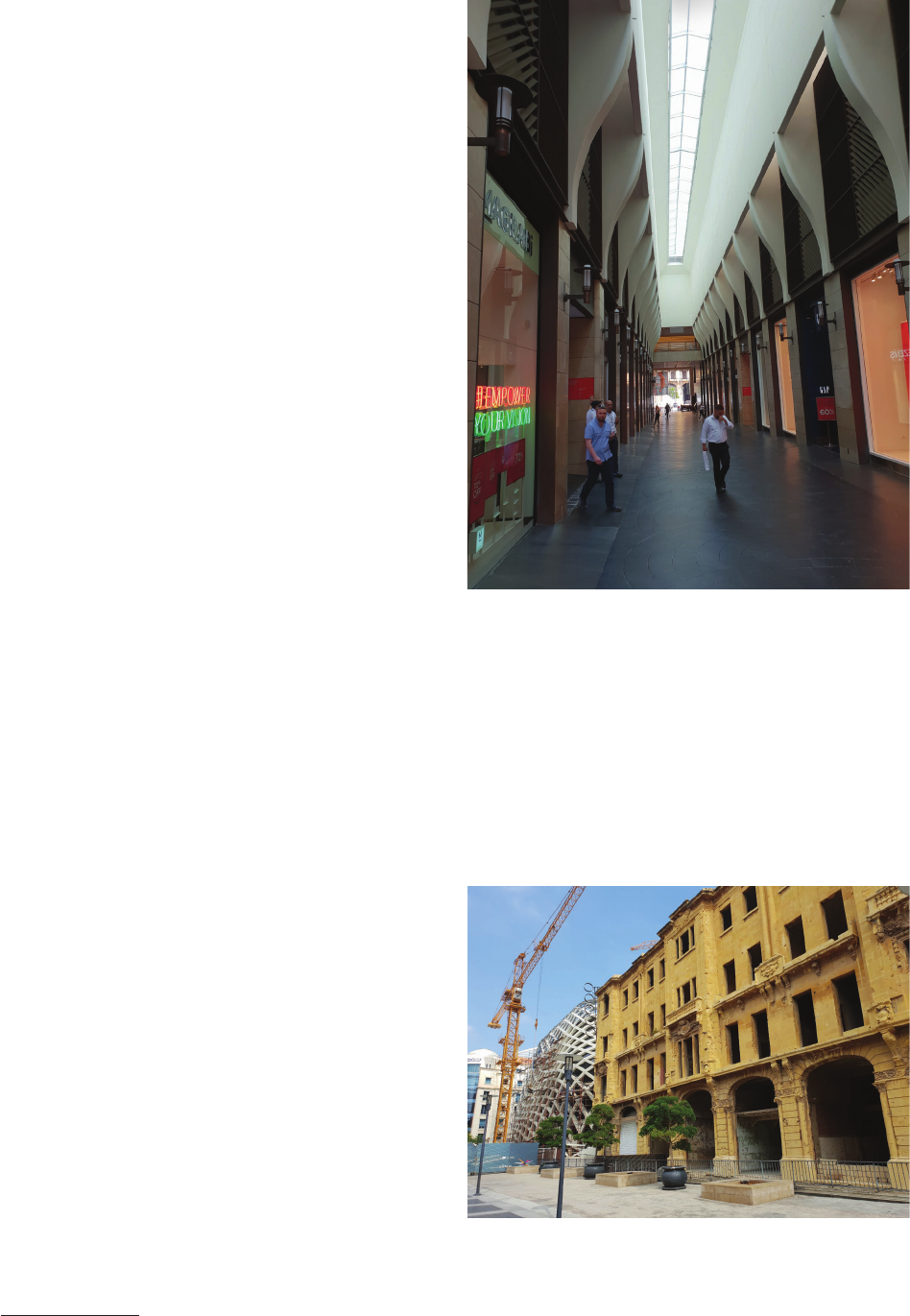

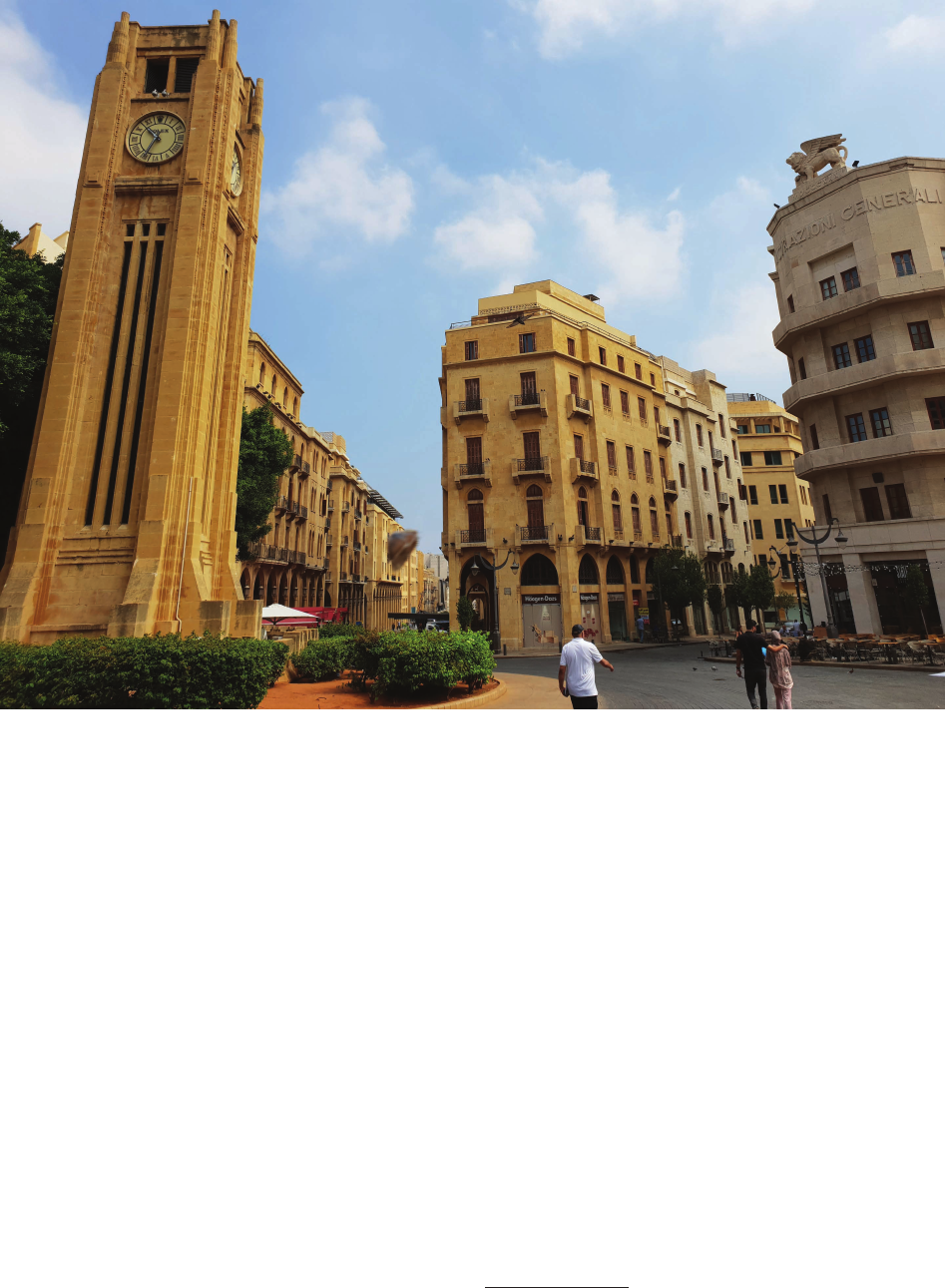

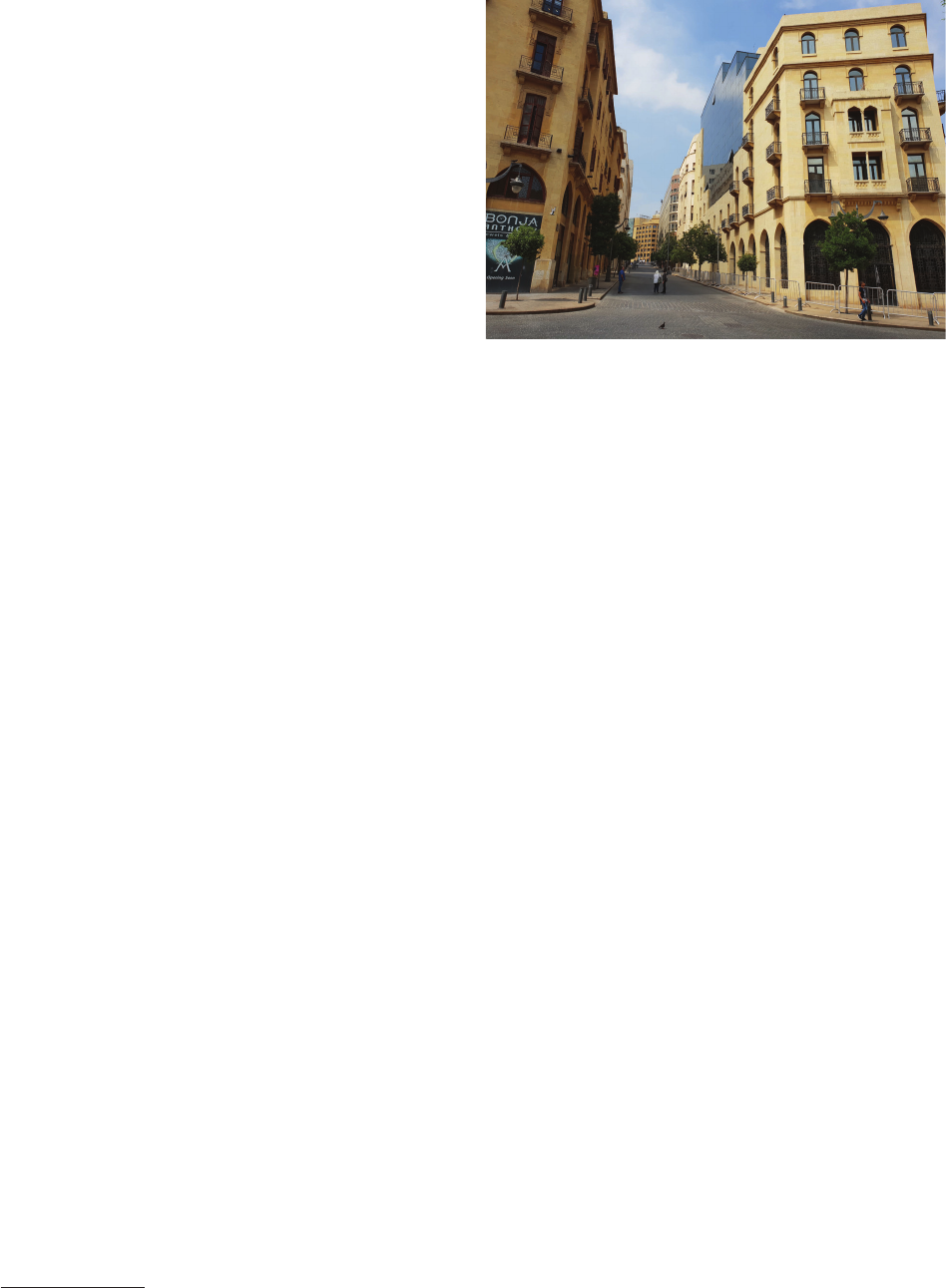

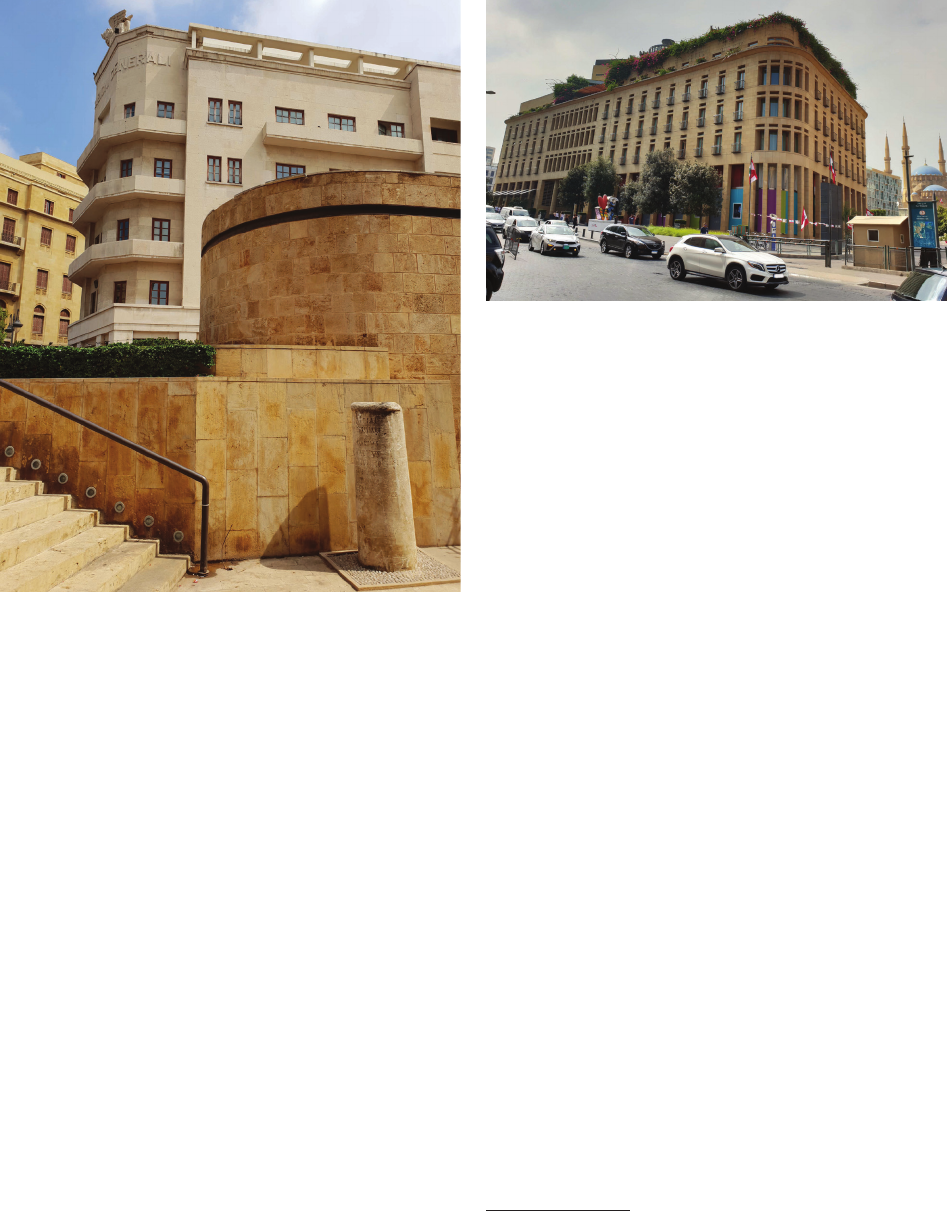

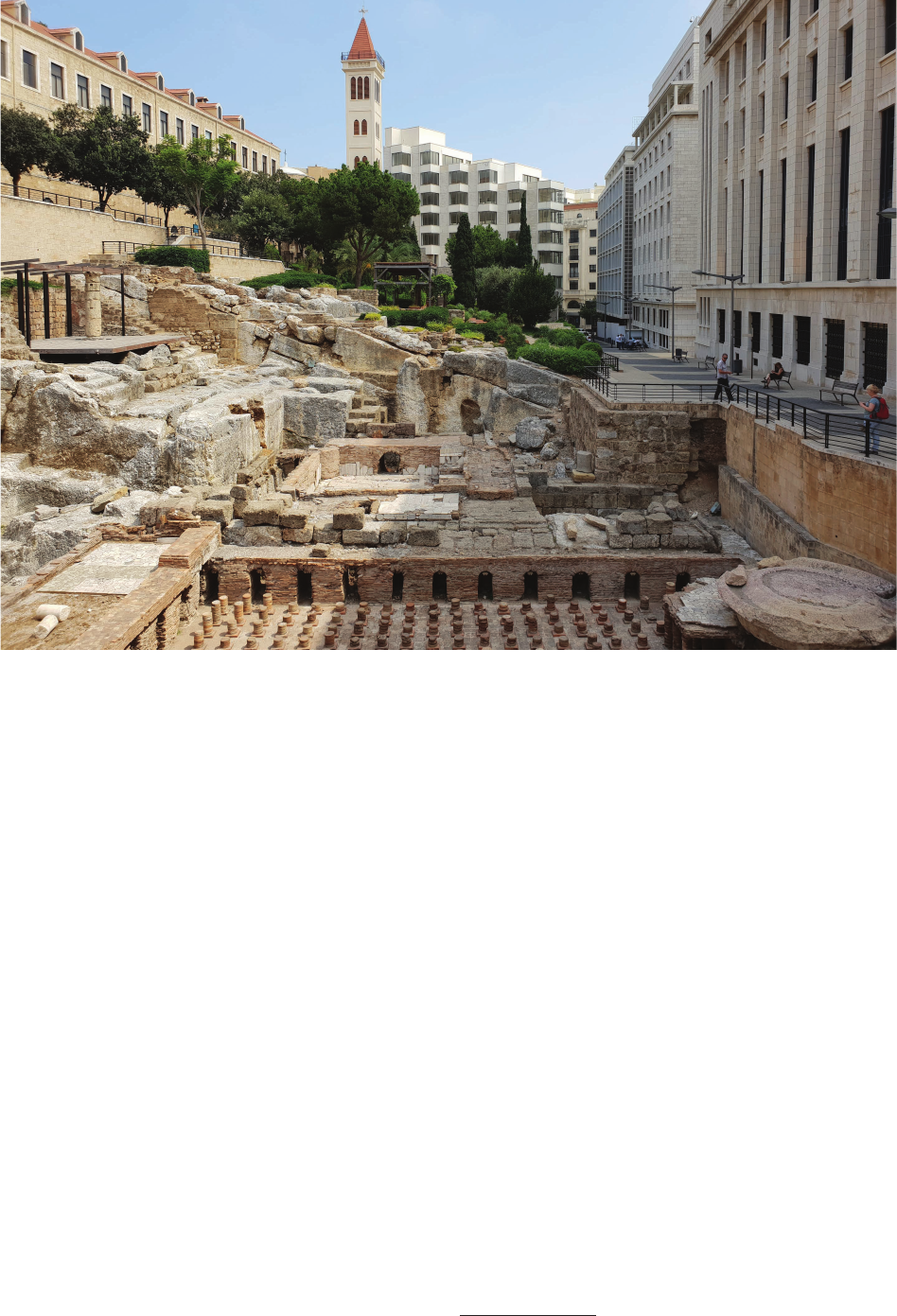

Of all the aforementioned capitals, Beirut has the larg-

est scale of urban design in the 19

th

century or Art Déco

aesthetics, which has become the fashionable nucleus of

the city. In fact the central, reconstructed historic district