82 Bartosz M. Walczak

results, when confronted with the actual condition of the

object, force us to look for solutions that would tell the

history of a property in the best possible way to the con-

temporary society.

At the same time, due to its specic history, the build-

ing, despite being part of the industrial heritage, is free

from negative associations caused by deindustrialization

and economic decline. The intimate scale of the building

also means that it is not aected by many threats typical

of degraded post-industrial properties.

Due to the irretrievable loss of function, the protection

of post-industrial buildings requires their adaptive reuse to

an incomparably greater extent than in the case of other

types of monuments. Activities of this kind can signicant-

ly contribute to the renewal (revitalization) of crisis areas,

a phenomenon characteristic of former industrial districts.

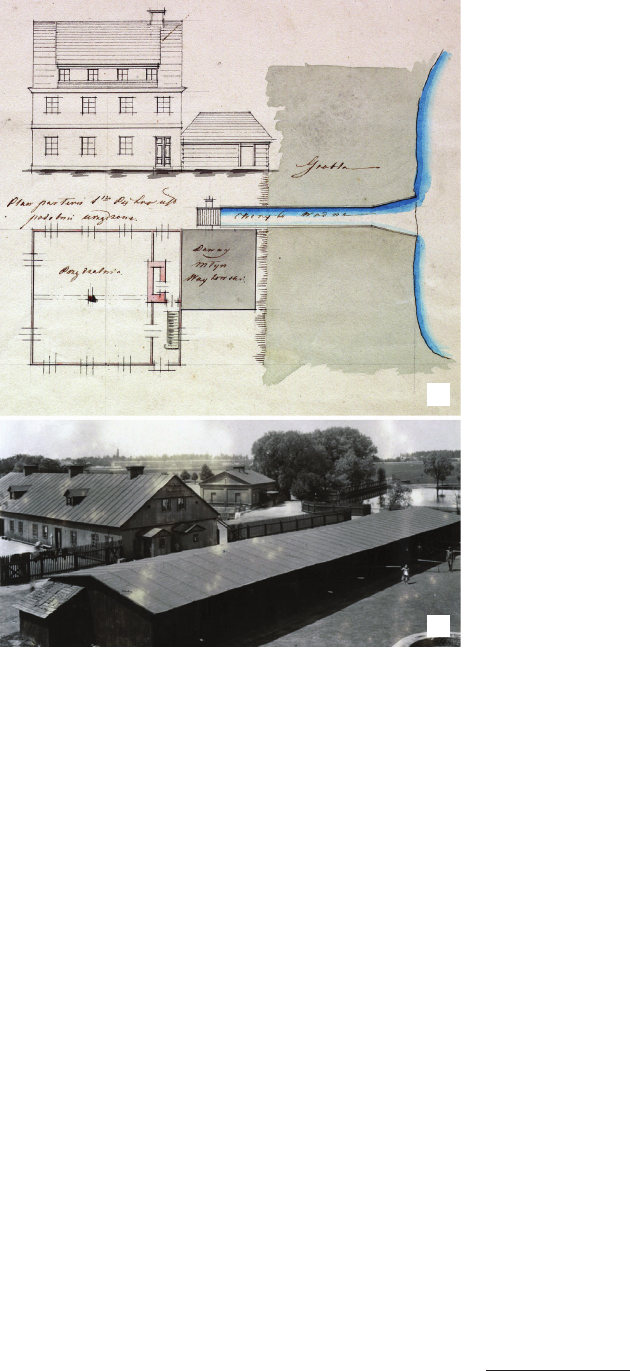

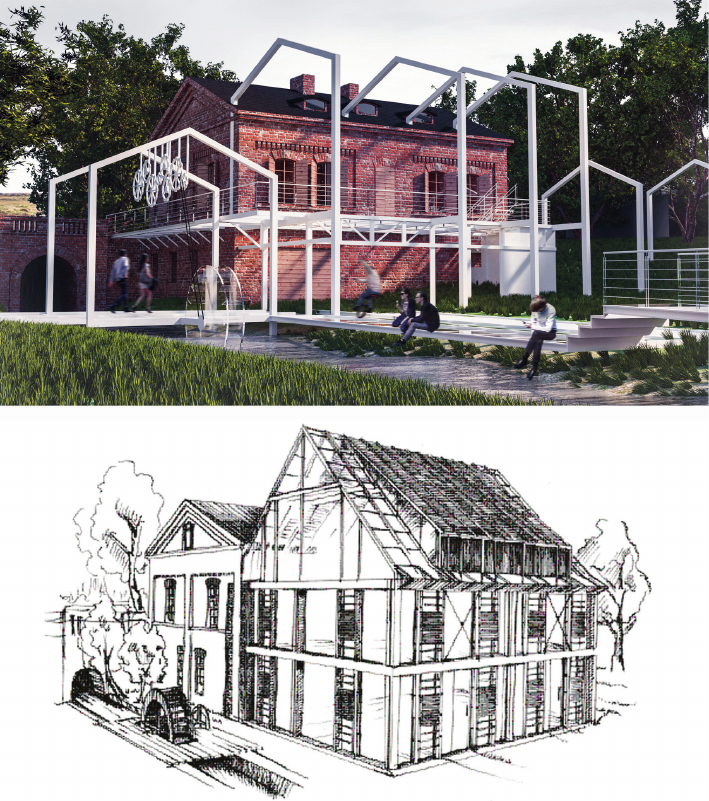

The problem task presented in this article made it pos-

sible to test the eectiveness of selected design strategies

that would allow us not only to preserve the memory of

the buildings that once existed in Wójtowski Młyn, im-

portant for the history of the city both in pre-industrial

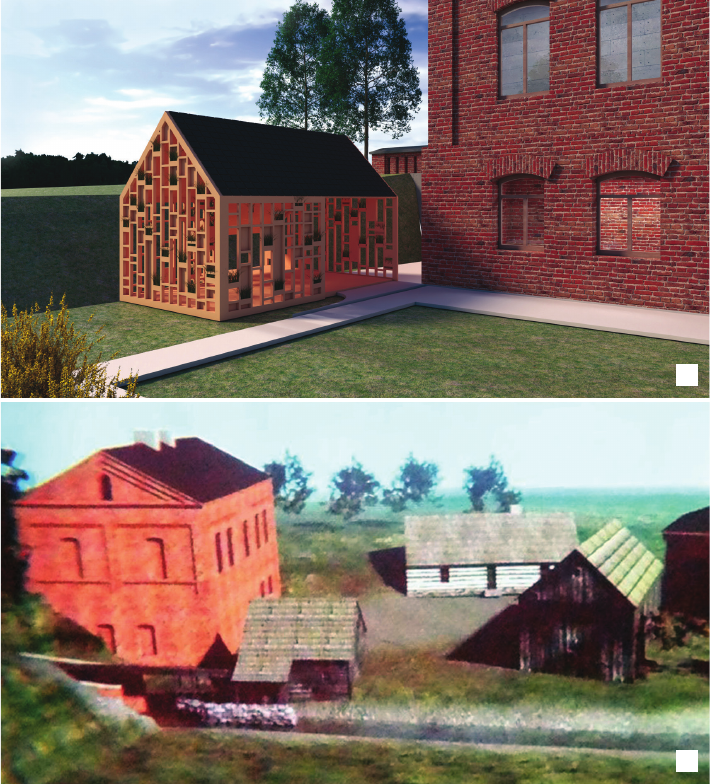

times and in the period of industrialization. Design should

therefore be treated as a research process leading to a new

interpretation of the site. In this approach, architectural

creation must be subordinated to the extraction and expo-

sure of identied cultural values. Since only “scraps” have

survived from the particular stages of the construction his-

tory, architectural solutions were needed that would bind

them together and, at the same time, be an eective tool

for telling stories from the palimpsestic past.

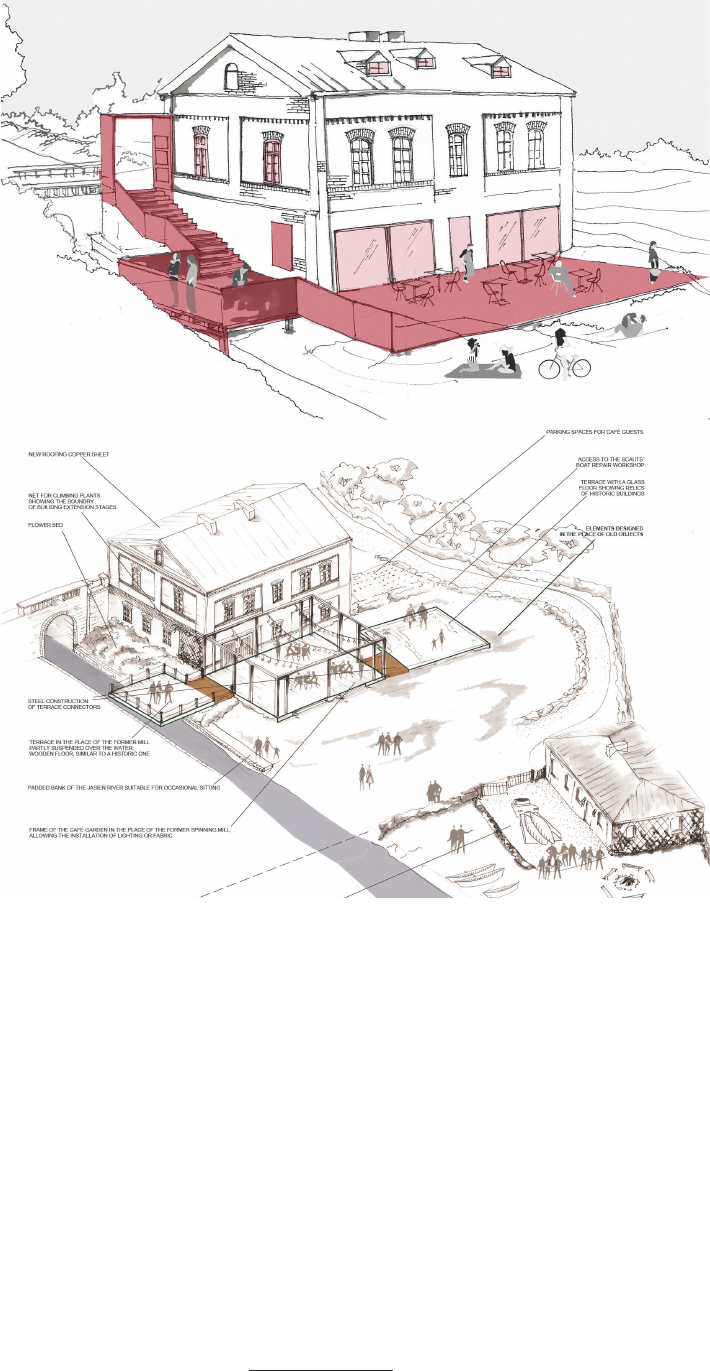

Based on the analysis of the identied approaches and

interpretations, the following observations can be made:

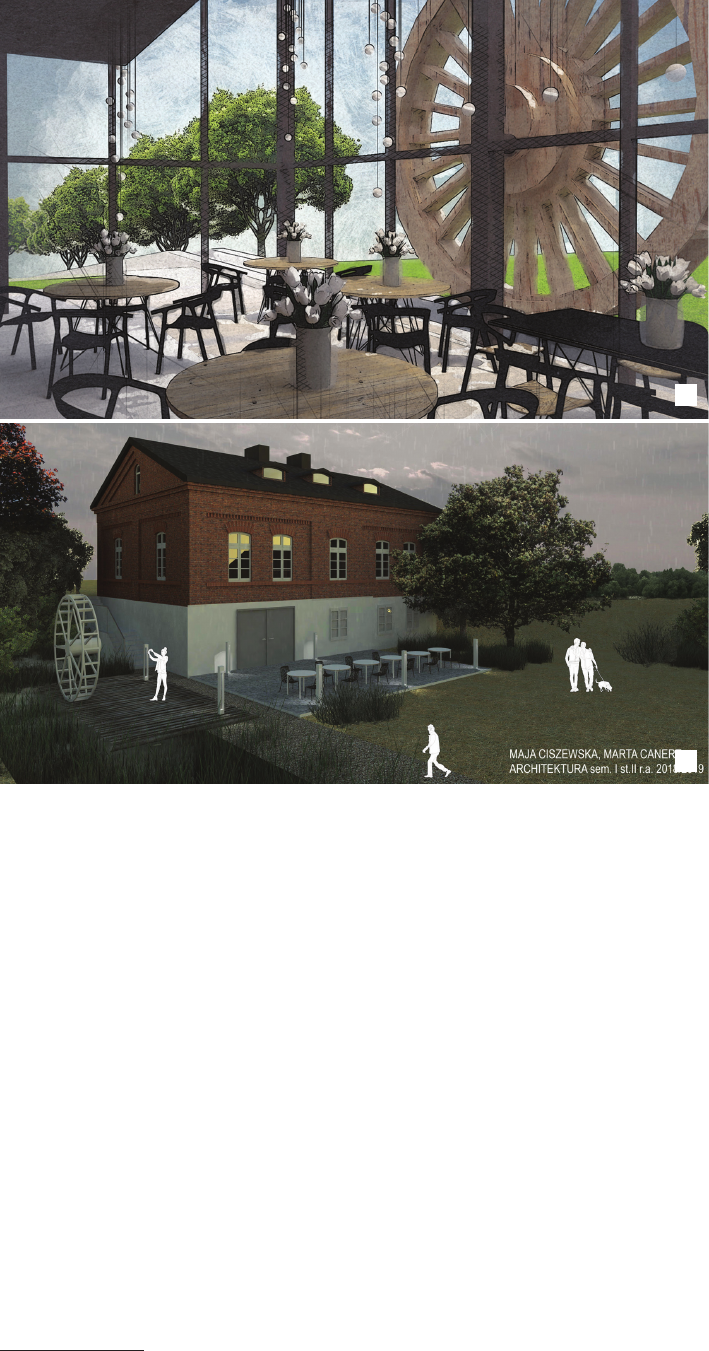

– choosing a leitmotif symbolizing the original func-

tion draws the recipient’s attention to the fact that the buil-

ding was something else than its architectural form sugge-

sts, but it does not fully refer to the complex history of the

place (it is more an anecdote than a story),

– creating an architecture that takes into account all

phases of transformation is a dicult task, but possible

to carry out provided that the narrative is well structured

(just like any complex, multi-threaded story),

– narration in architecture requires the appropriate se-

lection of forms and materials (e.g. reecting the state of

knowledge about the various stages of construction histo-

ry), and in addition, it should be understandable (and at-

tractive) for the contemporary recipient,

– it is especially dicult for young architects to be re-

strained and to understand that it is the subject of the story,

not the narrator, that should be at the centre of attention,

– the role of interpretation is of fundamental importan-

ce for the understanding of the object and the recognition

of its value by the contemporary recipient,

– the narrative must be adapted to the rank of the histo-

ric object and the available means, and consequently take

various forms.

In addition to issues strictly related to the narrative, the

discussed projects also revealed several problems essen-

tial for the eective interpretation of monuments, espe-

cially those belonging to industrial heritage.

First of all, it is signicant that, apart from the water

wheel technology, the engineering aspect of heritage has

been omitted, which is, however, problematic not only in

Poland but almost everywhere in the world [16], [17].

Secondly, preserving the genius loci turns out to be

a particularly dicult design challenge. The atmosphere

of the place is ephemeral and dicult to capture and

translate into architectural language. Moreover, changes

can easily destroy it. Architects must show the appropri-

ate sensitivity to successfully design solutions that respect

the atmosphere of a place with a high concentration of

cultural values.

Another important issue is adaptive reuse. It is of cru-

cial importance for monuments to be socially useful be-

cause emotional bonds are built through everyday contact.

It is equally important to present a technical monument in

such a way that its original function is understandable for

those who interact with the heritage. While most people

can easily imagine how a baroque palace or even a medi-

eval castle functioned in the past, members of post-indus-

trial societies are usually helpless when it comes to indus-

trial facilities. It is dicult to appreciate a monument that

is not understood. Therefore, in the case of sites related

to production or technology, interpretation explaining the

process determining the appearance of a historic object is

of particular importance. It is also worth explaining other

issues that allow for a better understanding of the monu-

ment and its embedded system of meanings.

To sum up, the architectural narrative concerning cul-

tural heritage can take various forms, which was perfectly

demonstrated by the discussed projects, whose authors af-

ter graduation will hopefully be better prepared to perpet-

uate the memory of (not only) industrial heritage.

Translated by

Anetta Kępczyńska-Walczak

References

[1]

Dillon S., Reinscribing De Quincey’s palimpsest: the signicance

of the palimpsest in contemporary literary and cultural studies,

“Textual Practice” 2005, Vol. 19, Iss. 3, 243–263, doi: 10.1080/

09502360500196227.

[2] Palimpsest, [in:] Słownik języka polskiego, PWN, https://sjp.pwn.pl/

szukaj/palimpsest.html [accessed: 7.03.2023].

[3] Wierzbicka A.M., Architektura jako narracja znaczeniowa, Ocyna

Wydawnicza PW, Warszawa 2013.

[4] Niezabitowski A., Narracja architektoniczna – interpretacje, speku-

lacje czy fakty empiryczne?, “Kwartalnik Architektury i Urbanisty-

ki” 2016, t. 61, z. 1, 5–30.