Zachód II housing estate in Szczepin in Wrocław – a place built anew 127

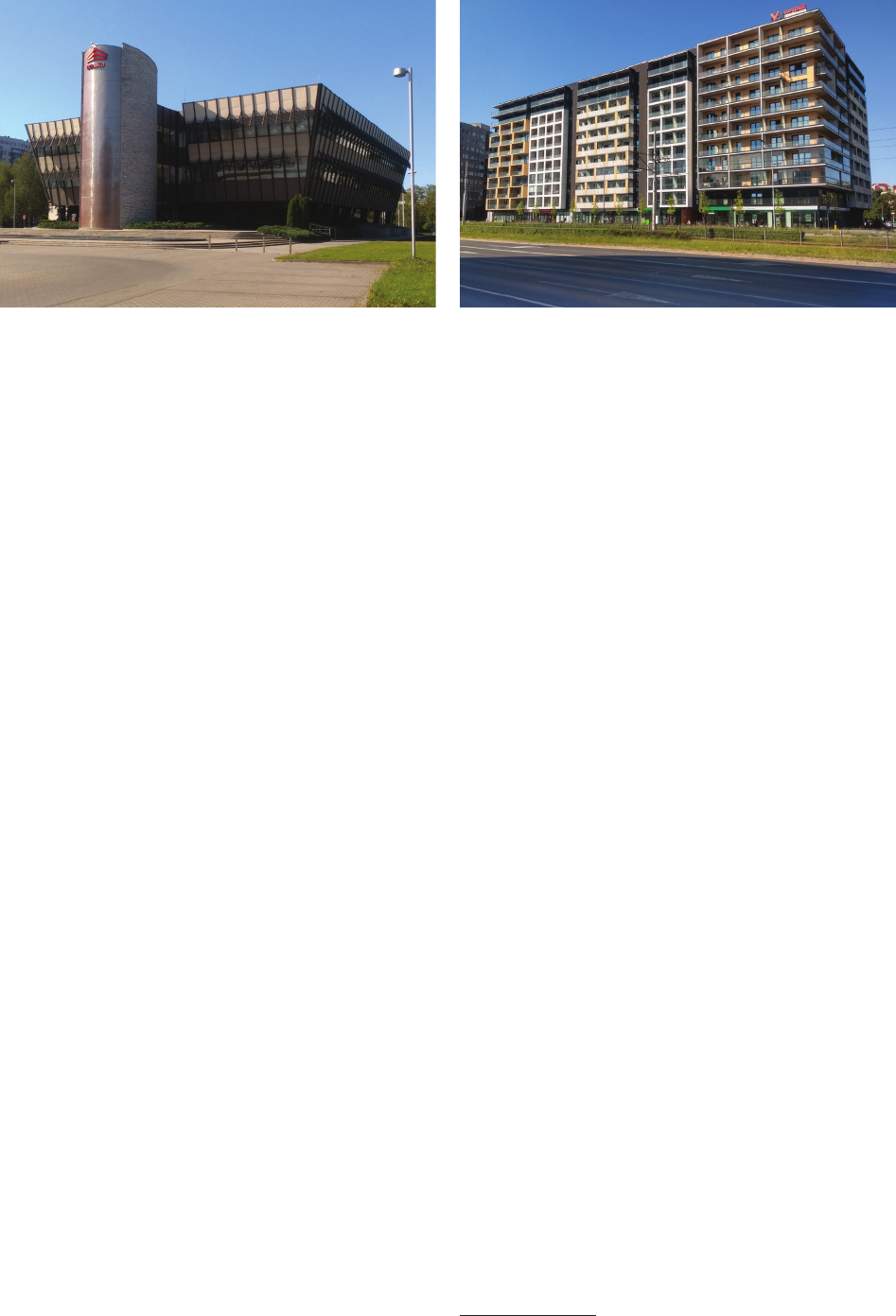

neighbor. The lack of dialogue between the present and

history is not justied by the quality of the architecture

of the apartment building itself, which has been provided

with repetitive façades, typical of residential houses under

construction. A mosaic of several fashionable solutions –

façade “templates”, which were probably intended by the

designers to divide the optically long façade on the side of

Legnicka Street and soften its huge scale, is not enough to

create a new, aesthetic dominant of Strzegomski Square.

And only such action could possibly explain the complete

lack of respect and understanding for the work of previous

generations of architects.

Summary

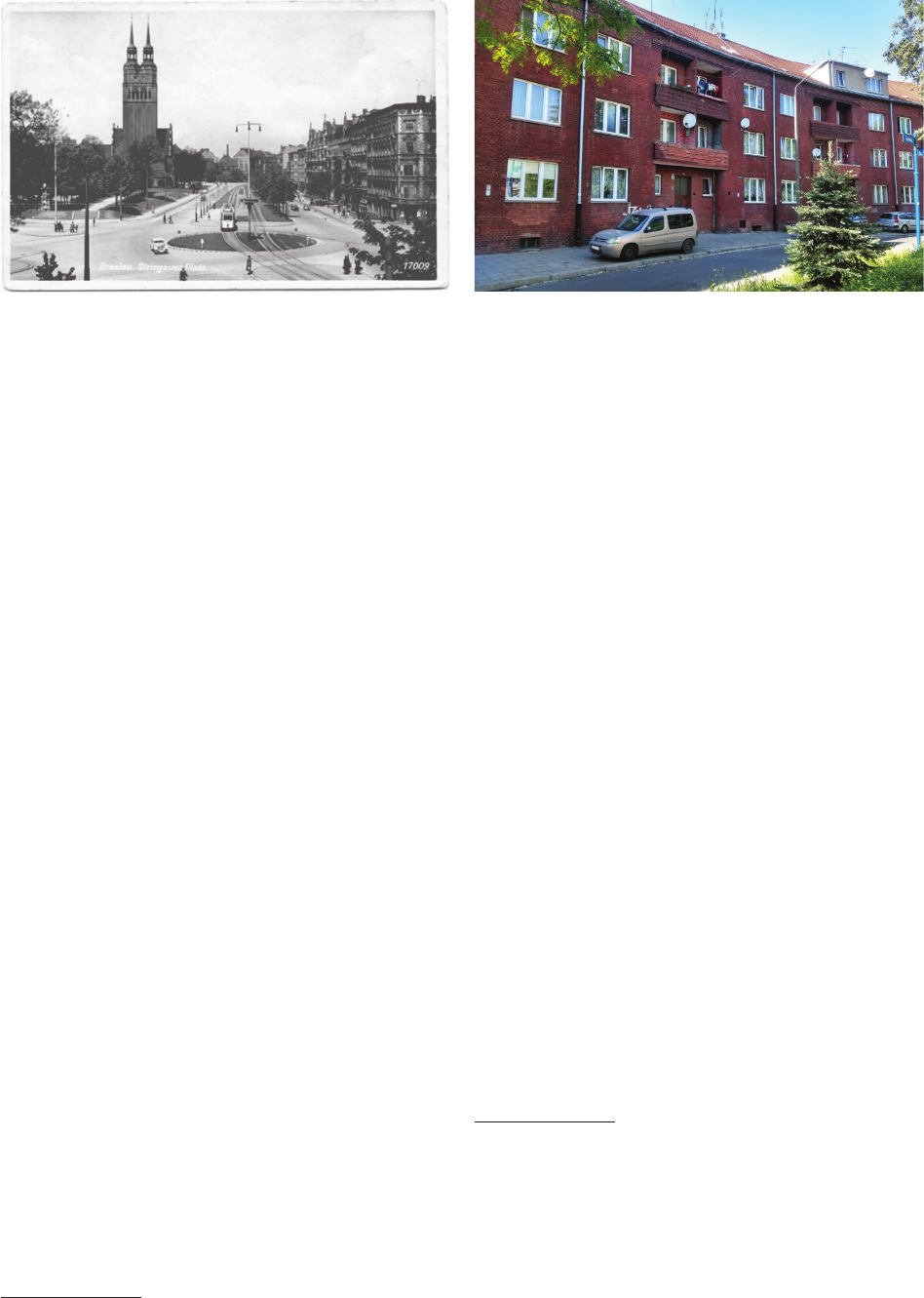

Archival photos, lms and other source materials show

the beauty of pre-war Breslau, the capital of Lower Sile-

sia, a metropolis with a rich, centuries-long history, but

also with bold visions of future development. It is un-

doubtedly regrettable that this Wrocław did not survive

the war drama and began its new historical chapter in 1945

as a city in ruins. A city that had to be not only rebuilt, but

in large part built from scratch. Faithful to the historical

original, reconstructions and reconstructions were possi-

ble only in a small part of the devastated areas, thanks to

which the architects received a huge testing ground for the

implementation of modern urban and architectural ideas,

responding to the needs of rapidly changing societies. Al-

most all of southern and western Wrocław was built from

scratch. The new districts changed the urban landscape as

their urban composition diered signicantly from his-

torical rules and principles. Time constantly veries the

achievements of that time. Discussions and assessments

of the architectural achievements in Poland of the com-

munist era are still ongoing. Filip Springer, in the title of

one of his “architectural” reportages, called the objects

of this era symptomatically ill-born [18]. Jakub Lewicki,

historian of architecture and conservator of monuments

noted in one of the interviews: The stigma of the People’s

Republic of Poland is a very important element, but most

of these buildings are extremely neglected and degraded,

their condition is deteriorating and most often deprived of

any care. Hence, buildings that were beautiful, functional

and useful, today are dirty, neglected hovels. […] I wish

that everyone would look at 20

th

century objects more

sympathetically. He did not immediately dismiss them

as nasty blocks, but tried to understand the intentions of

their creators and tried to imagine them not neglected, not

dirty, but still clean, eective and useful [19].

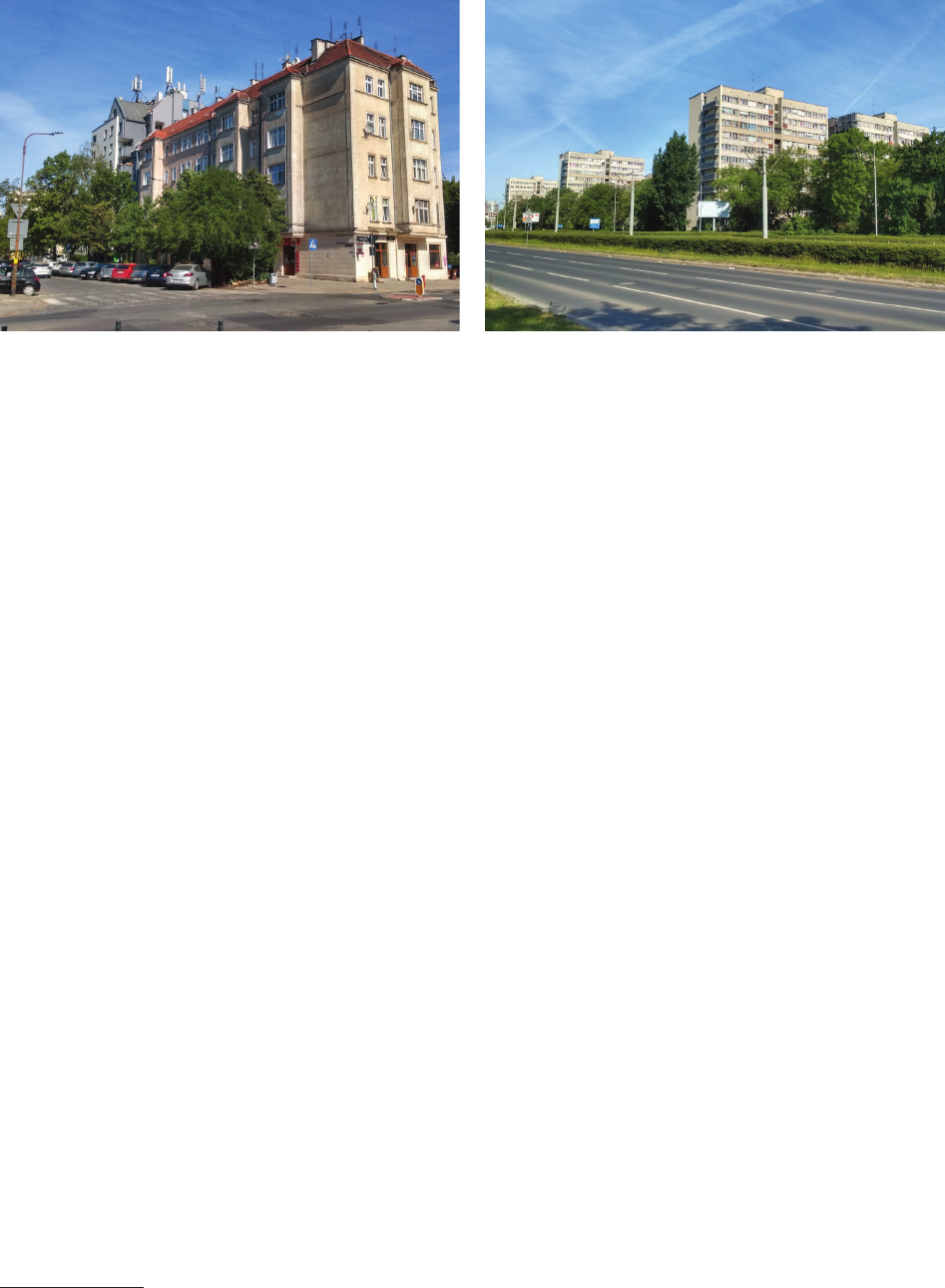

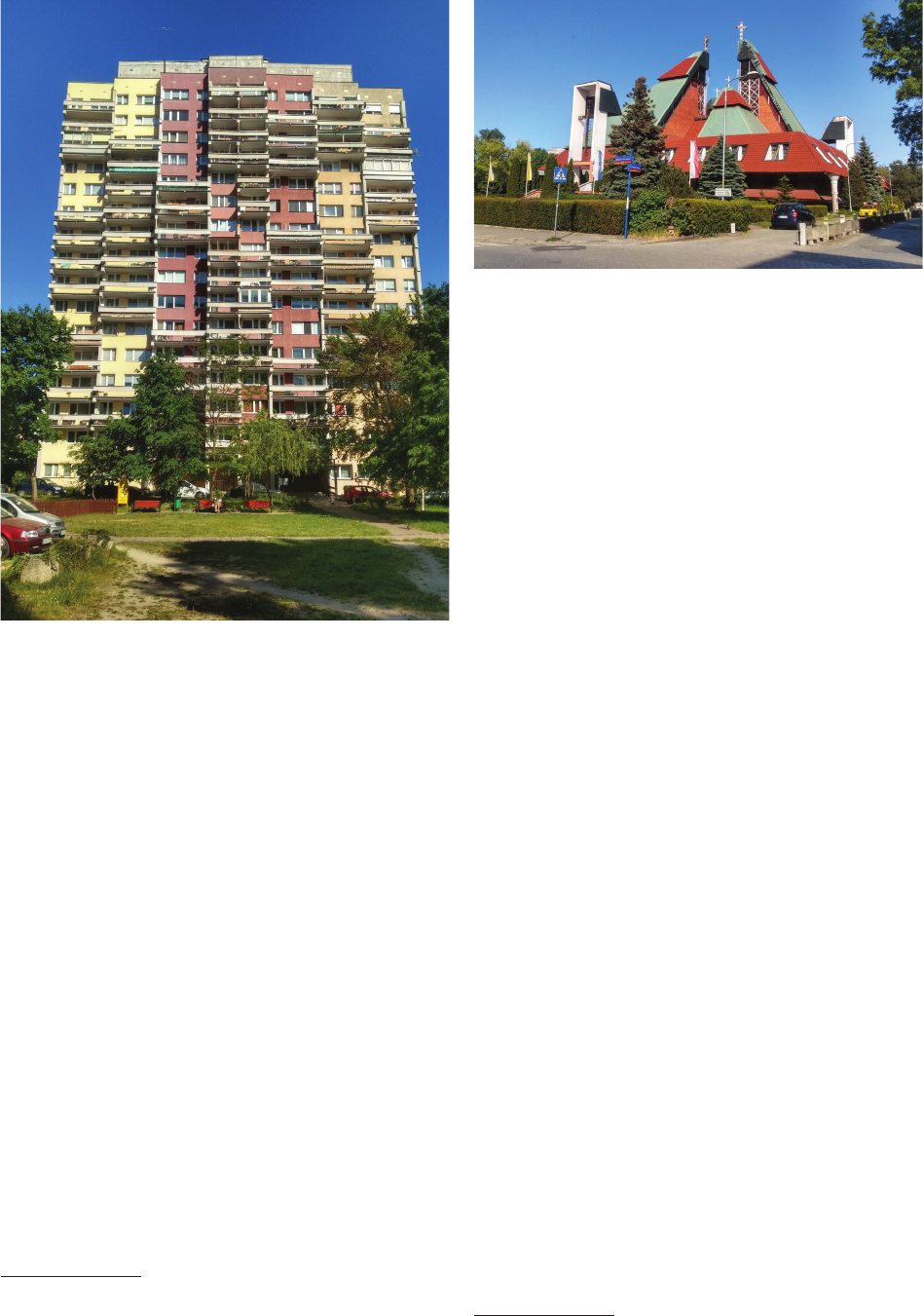

The analysis of the Zachód II estate proves that it is

a very interesting experiment and a testimony of its time,

and at the same time it is a value that should be protect-

ed. A great challenge in the modernization of post-war

architecture is maintaining, rstly, respect for the origi-

nal idea, and secondly, the greatest possible degree of the

original substance – while meeting the requirements of the

construction industry and the investor’s expectations [20,

p. 204]. Many elements that make up the original expres-

sion of the estate have not survived. First of all, the origi-

nal “strip” colors of the residential blocks’ elevations have

not been preserved. Like most large-panel buildings, they

are successively insulated, which is an understandable and

most economically justied process. The new colors on

the insulated façades do not, however, try to refer to the

Molicki project in any way. Window joinery, replaced by

the tenants themselves, does not reproduce the original

rhythm of divisions with characteristic vent windows. The

recently rebuilt balconies in apartment blocks receive bal-

ustrades in a form and material that is foreign to the proto-

types. The list of threats goes on. It was discussed earlier

about increasing the density of buildings that changed the

composition of the estate. Therefore, the prospects for the

urban and architectural protection of the Zachód II estate

are not very optimistic. It is a pity, because the experienc-

es of other countries, but also fortunately emerging Pol-

ish examples, prove that the cultural heritage of post-war

modernism is beginning to be perceived as a great value.

Translated by

Jan Urbanik

References

[1] Dudek P., Koncepcje odbudowy powojennego Wrocławia 1945–1956

– między miastem prowincjonalnym a drugą metropolią, “Przegląd

Administracji Publicznej” 2013, nr 2, 59–68.

[2] Antkowiak Z., Stare i nowe osiedla Wrocławia, Zakład Narodowy

im. Ossolińskich, Wrocław 1973.

[3] Zabłocka-Kos A., Przedmieście Mikołajskie w XIX i XX wieku na

tle innych przedmieść wrocławskich, [in:] H. Okólska (red.), Przed-

mieście Mikołajskie we Wrocławiu, Muzeum Miejskie Wrocławia,

GAJT, Wrocław 2011, 10–17.

[4] Tyszkiewicz J., Historia Przedmieścia Mikołajskiego po II wojnie

światowej, [in:] H. Okólska (red.), Przedmieście Mikołajskie we

Wro cławiu, Muzeum Miejskie Wrocławia, GAJT, Wrocław 2011,

196–200.

[5] Gabiś A., Niejako w cieniu… – powojenna zabudowa Przedmieścia

Mikołajskiego, [in:] H. Okólska (red.), Przedmieście Mikołajskie we

Wrocławiu, Muzeum Miejskie Wrocławia, GAJT, Wrocław 2011,

209–217.

[6] Górska M., Osiedle Szczepin Theo Eenbergera, [in:] H. Okólska

(red.), Przedmieście Mikołajskie we Wrocławiu, Muzeum Miejskie

Wrocławia, GAJT, Wrocław 2011, 88–92.

[7] Gabiś A., Całe morze budowania. Wrocławska architektura 1956–

1970, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław 2019.

[8] Cymer A., Architektura w Polsce 1945–1989, Centrum Architektu-

ry, Narodowy Instytut Architektury i Urbanistyki, Warszawa 2018.

[9] Tomaszewicz A., Majczyk J., Anna i Jerzy Tarnawscy, SARP Wro-

cław, Wrocław 2016.

[10] Analiza funkcjonalna osiedli Wrocławia, I. Mironowicz (red.),

Fun dacja Dom Pokoju, Wrocław 2016.

[11] Lis A., Struktura przestrzenna i społeczna terenów rekreacyjnych

w osiedlach mieszkaniowych Wrocławia z lat 70.–80. ubiegłego

stulecia, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego, Wrocław

2011.

[12] Podolska A., Dul A., Przestrzenie rekreacyjne na osiedlu mieszka-

niowym Szczepin we Wrocławiu – analiza stanu zagospodarowania,