%HWZHHQ(XURSHDQGWKH(DVW±GUDIWRQDUFKLWHFWXUDOODQGVFDSHRI%XFKDUHVW 121

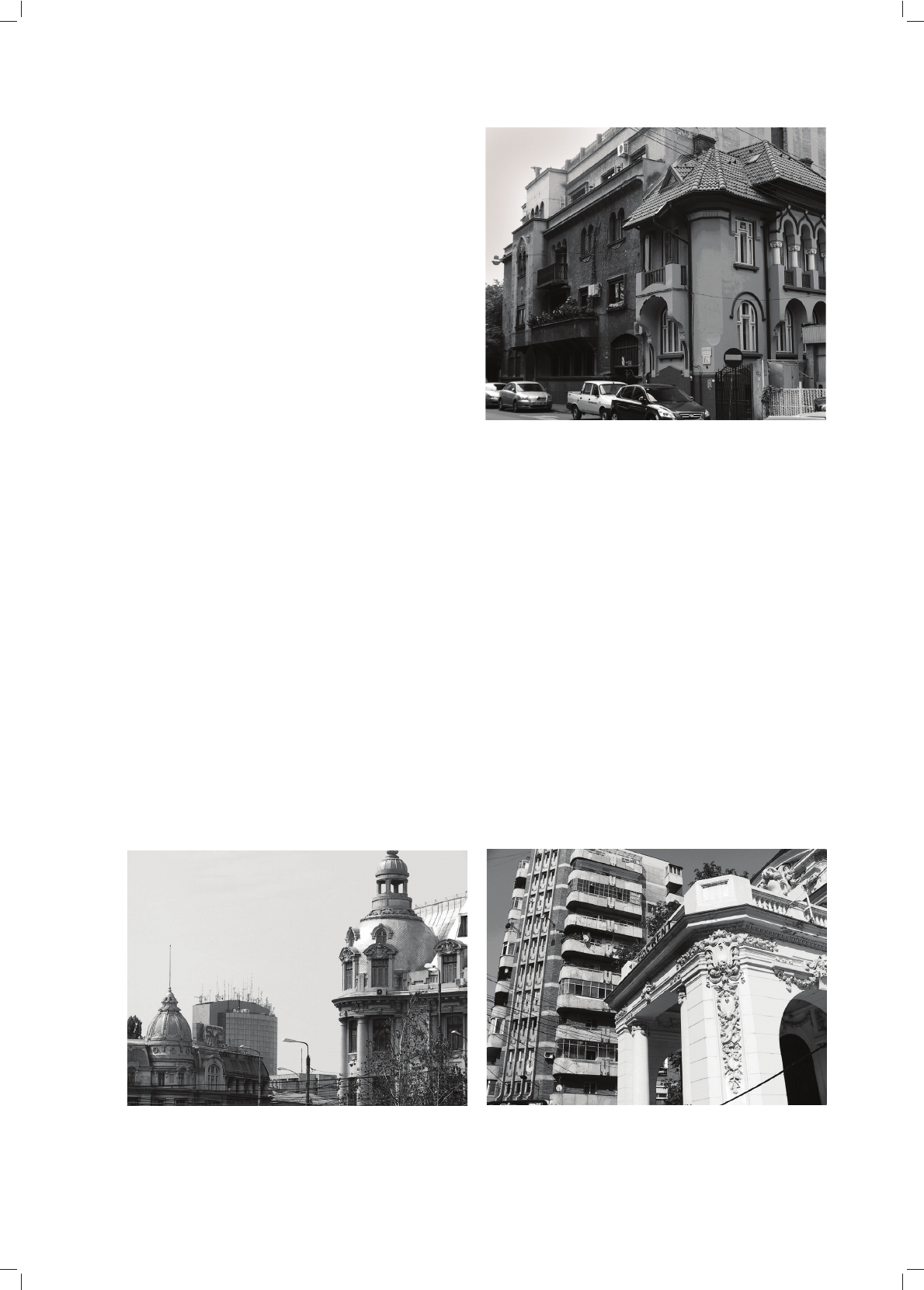

International style, including monument office buildings, resi-

dential buildings and houses, were designed in Bucharest

especially in the middle of the 1930s, when, after the great

crisis, the building investments became the best means to save

the capital [4] (Fig. 8, 9).

Despite the fact that the Romanian modernism was an

imported idea, the avant-garde architecture of Bucharest is

extraordinary on the European scale and its modern designs

are remarkable. It is surprising how easily the interwar soci-

ety adopted the completely new style of architecture. On the

other hand, the activities of the state in respect of social hous-

ing – so typical of modern ideas – were insufficient. The new

style was mainly applied in private building. Modernism was

perceived separately from its original, social principles and

consequently it was only a kind of fashionable modern cos-

tume (Fig. 10, 11).

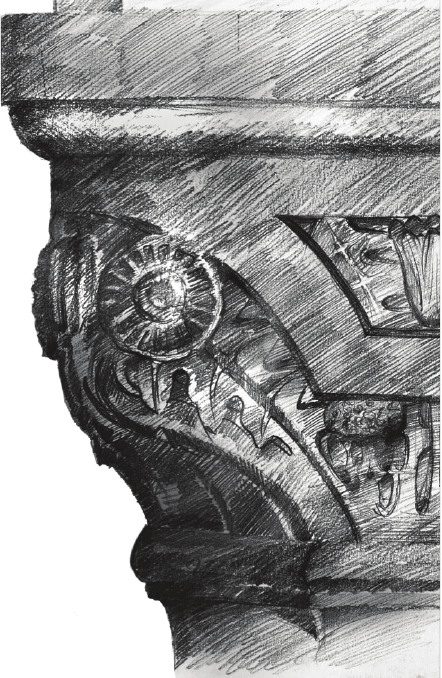

That is why the specific features of Bucharest avant-

garde focus on the external form of the buildings.

Architects freely and skillfully used all resources of mod-

ern formal means. New architecture used asymmetrical

FRPSRVLWLRQ KRUL]RQWDO UK\WKPV EDQG DQG URXQG ZLQ-

dows, loggias and balconies, brise-soleil, ship balus-

trades, rounded corners resembling the designs by Erich

Mendelsohn, etc. The minimalist solutions were not

popular – on the contrary – the buildings were composed

of many sections and they had a lot of details (cornices,

frames, etc.) [3].

This way modernism of the capital city falls in line

with the long tradition of extravert and decorative

architecture of Bucharest. Frequently, this continuity

can be perceived literally when the functional archi-

WHFWXUH LQFOXGHV SRLQWHG DUFKHV %\]DQWLQH FROXPQV

or pseudo-Moorish bars as well as warm colors.

These surprising deviations from stylistic purity tes-

tify best to the uniqueness of the Romanian avant-

garde (Fig. 11).

The modern movement ended with the outbreak of the

6HFRQG :RUOG :DU ZKLFK UHVXOWHG LQ WKH VXEVWDQWLDO

destruction of the city. After 1947, Romania became

a Socialist Republic. New authorities considered avant-

garde bourgeois formalism and it was doomed to artistic

void. Instead, there was a return of the spirit of neo-clas-

sicism. It did return but in a distorted form.

This is when socialist realism began, which was also

known in other countries of so called Eastern Bloc. The

temporary turn towards so called socialist modernism in

the 1960s–1970s did not stop an urban catastrophe. The

huge earthquake in 1977, which did a lot of damage in the

historic fabric of Bucharest, became a pretext for party

GHFLVLRQPDNHUVOHGE\1LFRODH&HDXúHVFXWRLPSOHPHQW

the plans to remodel the capital city and turn it into a

propaganda flagship of socialist Romania. In 1980, the

FOHDQLQJRIWKHDUHDIRUWKH³QHZVRFLDOLVWFLW\´ZKLFKZDV

planned on the south side of the existing city center by the

'kPERYLĠD5LYHULQWKHDUHDRIWKHROGHVWPHGLHYDOSDUW

of Bucharest began. In order to execute that undertaking

the area of about 7 km

2

of the city, that is about 1/3 of the

area of the city center, was leveled. About 40 000 resi-

dents were relocated. The old street network, the hum-

PRFN\ODQGVFDSHDGR]HQRUVRRIRUWKRGR[FKXUFKHVDQG

monasteries as well as numerous other valuable, historic

buildings were completely destroyed [1].

The plan of the new design was based on extremely sim-

plified layout. It had two main elements: the “People’s

+RXVH´DQGWKH³$YHQXHRI9LFWRU\RI6RFLDOLVP´)LJ

The construction of the People’s House – one of the big-

gest buildings in the world, which was built in the years

1984–1989 according to the plans prepared by a team of

a few hundred architects – required a lot of effort. The com-

SOH[ZKLFKZDVEXLOWUHPLQGHGWKH%DE\ORQLDQ]LNNXUDWLQLWV

SURSRUWLRQVDQG9HUVDLOOHVLQLWVDUFKLWHFWXUH7KHVFDOHDQG

grandeur of the structure defies all classification.

7KH³$YHQXHRI9LFWRU\RI6RFLDOLVP´LVDILYHNLORP-

HWHUORQJD[LV D IHZ GR]HQ PHWHUV ORQJHU ± ZKLFK ZDV

a source of its builders’ pride – than the Avenue des

Champs-Élysées in Paris. A number of government and

apartment buildings were designed with rows of trees and

tens of fountains along the sides of the Avenue. The

monumental Unirii Square with commodity warehouses

was located in the area where the Avenue crosses the

existing south-north axis.

The schematic and monumental architecture of these

buildings is a combination of socialist realism, a sort of

Ricardo Bofill’s European post-modernism and the style

of official building in North Korea, with which the dicta-

tor maintained close relations (Fig. 13).

New Socialist City

Fig. 12. The Palace of the Parliament (former People’s House) at the

FORVLQJRIWKHYLHZLQJD[LVSKRWR:-DQXV]HZVNL

,O%U\áD3DáDFX3DUODPHQWXGDZQLHM'RPX/XGRZHJRQD

]DPNQLĊFLXRVLIRW:-DQXV]HZVNL)