„Węzły i struktury przestrzenne” – w hołdzie Stefanowi du Château / “Nodes and Spatial Structures”, a tribute to Stéphane du Château 43

Inżynier z wyobraźnią

Podstawowe idee

Stefan du Château był jednym z najbardziej produk-

tywnych inżynierów w dziedzinie struktur przestrzen-

nych 2. poł. XX w. Był specjalistą od wykorzystania rur

do budowy konstrukcji i blisko współpracował z Zyg-

muntem Sta nisławem Makowskim, który działał w Lon-

dynie (w Imperial College), a później także w Guild-

fordzie (w Space Structure Research Centre

2

). Różnica

po między słowami „przestrzeń” a „przestrzenny” nie ma

znaczenia w niniejszym tekście

3

. Stefan du Château był

specja listą w dziedzinie geometrii i potrafi ł projekto wać

wszelkiego rodzaju struktury przestrzenne: ruszty dwu-

war stwowe, sklepienia, systemy podwójnie zakrzywio-

ne..., ale zawsze szczególnie interesowały go dwa zagad-

nienia: węzły oraz proces uprzemysłowienia. Każdy, kto

zajmował się strukturami przestrzennymi, wie, że kluczo-

wym zagadnieniem do rozwiązania w tym zakresie jest

projekt węzłów.

Węzły

• Rozwiązanie dwukierunkowe – Unibat

Na początku rozwoju badań nad rusztami dwuwars t-

wo wymi większość z nich była dwukierunkowa. Miały

one dwie równoległe warstwy – „górną” i „dolną” – z ele-

mentami wiążącymi pomiędzy nimi. Z geometrycznego

punktu widzenia jednym z rozwiązań było uzyskanie

względnego obrotu o 45° pomiędzy głównymi kierunka-

mi warstwy górnej i warstwy dolnej, z których każda była

kwadratową siatką. Stefan du Château był przekonany, że

to bardziej efektywne niż rozwiązanie „kwadrat na kwa-

dracie”. Potwierdzają to wyniki, które opublikowałem

w 1975 r. [3]; ciężar własny został znacznie zmniejszony.

Jestem wdzięczny Stefanowi du Château, Zygmuntowi

Stanisławowi Makowskiemu i Hoshyarowi Nooshinowi,

którzy zachęcili mnie do wykonania tej pracy podczas

mojej wizyty w Centrum Badań Struktur Przestrzennych

w Guildfordzie (1973).

Co było węzłem w takiej geometrii, w systemie Unibat?

Nic, ponieważ nie ma żadnych części węzłowych w tej

sieci dwuwarstwowej. Jest to stosowane w pira midach

o podstawie kwadratowej, montowanych przy użyciu jed-

nej poziomej śruby na rogach kwadratów, które stano wią

warstwę górną (podstawę piramid). Pozostałe krawędzie

piramidy są elementami usztywniającymi. Warstwa dolna

jest najprostsza: elementy nie są docinane do wymiarów

geometrycznych, całkowita długość rur jest zachowana,

ale są one zgniatane w odpowiednich odległościach i prze-

wiercane tak, aby wprowadzić w nie śrubę przechodzącą

przez dwa elementy warstwy dolnej krzyżujące się pod

2

Centrum Badań Struktur Przestrzennych.

3

W języku angielskim konstrukcje przestrzenne określa się termi-

nem „spatial structures”. Jednak Z.S. Makowski używał także określenia

„space structures” i założony przez niego ośrodek badawczy nazywa się

Space Structures Research Centre. Ten drugi termin jest obecnie

używany przede wszystkim w kontekście prac tego ośrodka.

(at Imperial College), and then in Guildford, Surrey (at

the Space Structure Research Centre). The difference be-

tween the two words “space” and “spatial” is meaning-

less in this paper. Stéphane du Château was a specialist

of geometry and was able do design all kinds of spatial

structures: double layer grids, vaults, double curved

systems... However, he was always concerned with two

problems: the node and the industrialization process. All

people who were involved in spatial structures design,

know that the main question to solve is the node design.

Nodes

• Bidirectional solutio n – Unibat

At the beginning of investigations into double-layer

grids, most of them were bidirectional. They contained

two parallel layers, “top” and “bottom” ones, and in be-

tween bracing members. Geometrically speaking one of

the solutions was to get a forty fi ve degrees relative ro-

tation between the main directions of the top layer and

the bottom layer, both being a square meshing. Stéphane

du Château was convinced that it was more effi cient than

a “square on square” choice. This was confi rmed by the

results that I published in 1975 [3]; self-weight was sig-

nifi cantly reduced. I am indebted to Stéphane du Château,

Zygmunt Stanisław Makowski and Hoshyar Nooshin who

urged me to do this work, when I visited the Space Struc-

tures Centre in Guildford (1973).

Which was the node for this geometry, for this Unibat

system? None, since there are no node parts for this dou-

ble layer grid. It is realized with square pyramids that are

assembled by a single horizontal bolt at the corners of

the squares that constitute the upper layer (basis of the

pyramids). The other edges of the pyramid are the brac-

ing members. The bottom layer is the simplest that can be

found: members are not cut to meet the geometrical sizes,

the whole length of tubes is kept, but they are crushed at

ne cessary distances and drilled so as to introduce a bolt

through two bottom layer members crossing at 90°, and the

apex of the pyramid where four bracing members are joined.

It can be said that this is a solution without nodes, or with

bolts as nodes: the simplest solution that could be found.

Lightness and transparency result from this design.

In 1976, I organized a colloquium on structures in Mont-

pellier [4], and for this event we assembled two double

layer grids so as to constitute a kind of vault inside our

University (Fig. 2).

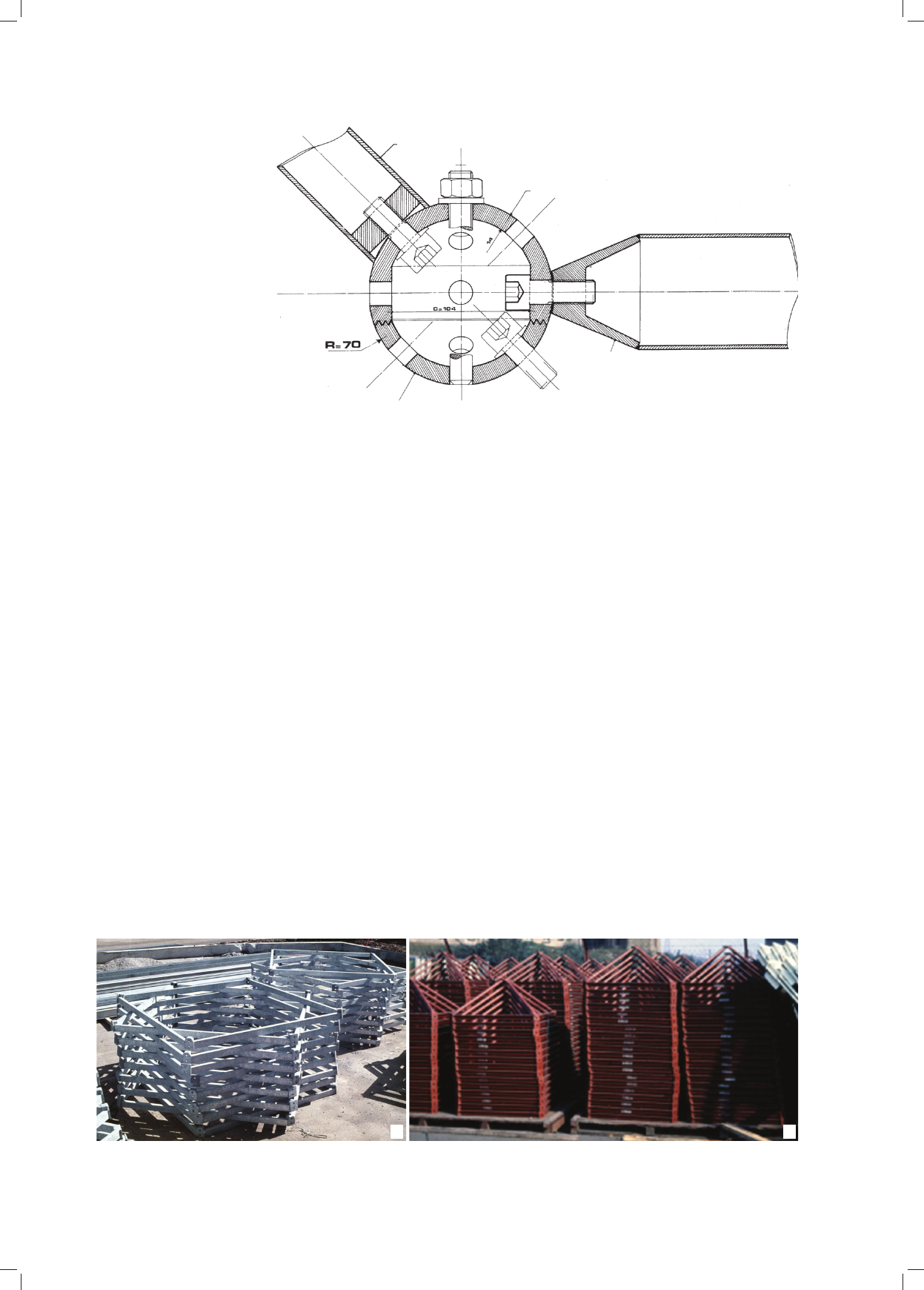

• Three directional solutions

Stéphane du Château was also aware of the structural

effi ciency of the double curved system and realized what

he called a “three directional” cupola in Grandval with

a very clever molded steel node. This cupola has a dia-

meter equal to 42 m. The radius of the complete sphere

is equal to 40 m. With a sag of 6 m, the total length of

members is 2,136 m, and there are 313 nodes.

Stéphane du Château was convinced by the rigidifying

effect of the double positive curvature, and simultane-

ously by the effi ciency of the three-directional orienta-

tion of the members that was also in accordance with the