10 Małgorzata Doroz-Turek, Andrzej Gołembnik, Justyna Kamińska, Kamil Rabiega

used for the construction of the chancel. This hypothesis

will however require future validation.

There are no remaining traces of the medieval choir

partition in the currently accessible area of the Church

of St. James. However, its existence may be speculated,

considering the Dominican regulations

4

, as well as the

conventional customs prevalent in monasteries during the

mid-13

th

century (Szyma et al. 2021, for instance). The

ceramic details originating from the 13

th

century which

still exist today serve as an additional rationale as they

are dicult to associate with other preserved locations

within the church or monastery grounds. Michał Walic-

ki (Walicki 1971, 216) had already anticipated the pres-

ence of ceramic, unidentied decorative pieces from the

choir screen. Zoa Gołubiew and, subsequently, Jerzy

Pietrusiński hypothesised that the preserved ceramic fea-

tures similar to those present in the main portal may have

originated from the analogium, an antealtar dividing wall

(Gołubiew 1975, 65, 66; Pietrusiński 1993, 142). Jur-

kowlaniec combined the rood screen removed in modern

times with a ceramic capital decorated with a crowned

head, discovered in 1907 and lost after 1968 (Jurkowla-

niec 2021, 228, fn. 17)

5

, as well as numerous other ceram-

ic elements that are currently preserved in the Diocesan

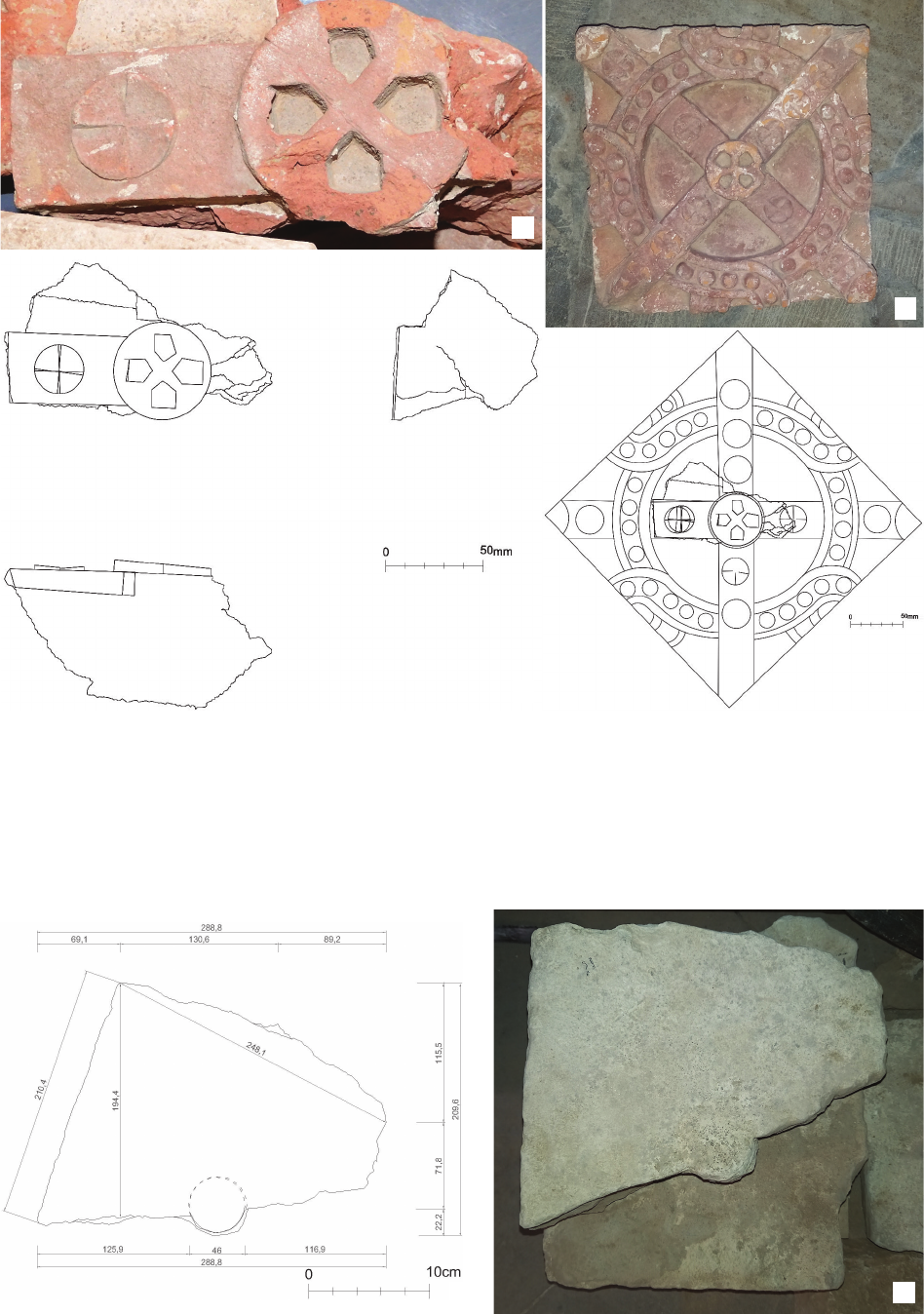

Museum in Sandomierz. It is probable that the ceramic

tile, a piece of which was discovered in the excavation,

initially constituted a part of the rood screen of the Church

of St. James. Nonetheless, this will require verication in

the subsequent stage of research.

An additional structure, which could also potentially

date back to the medieval period, was a stone foundation

(k. 3) intended for an unidentied construction. Perhaps,

it should be associated with the destroyed, initial Martyrs’

Chapel, referred to in written records and earlier research

6

,

as well as indicated in illustration records from the early

20

th

century at the rst span of the northern aisle from

the east (Wojciechowski 1910a, plan of the church depict-

ed on p. 209). Alternatively, this wall could be connected

4

The obligation to erect rood screens in Dominican churches was

established in 1249 by the General Chapter’s directive, which stipulated

that the friars must remain unseen to the secular individuals while

transitioning in and out of the choir – refer to (Meersseman 1946, 163;

Sundt 1987).

5

Gołubiew believed that this component originated from the portal

jamb; however, there is in fact no unoccupied space where it could

possibly be accommodated (cf. Gołubiew 1975, 34, 195).

6

Rev. Melchior Buliński postulated the presence of a pre-existing

chapel situated at the terminal end of the northern aisle of the church,

which, in his opinion, was erected to pay tribute to the Martyrs from

Sandomierz: […] even though it might not have constituted a full

chapel,

there was, at a minimum, a distinct rise in the form of a rotunda

positioned over the roof of the corresponding nave, with the observable

remnants over the vault remaining visible to this day (Buliński 1879,

293). Similar assertions were made by Wojciechowski, possibly draw-

ing from Buliński’s narrative: In 1600, the Martyrs’ Chapel was con-

structed by Teol Semberg, the castellan of Kamieniec, replacing the

pre-existing chapel carrying the same name located on the northern

aisle (Wojciechowski 1910a, 209). In another place, the architect noted

that, as early as the 16

th

century, a chapel characterised by a “at, dome

vault” was situated at the terminus of the northern aisle (Wojciechowski

1910b, 688). Wojciechowski noted the presence of the domed vault on his

designed plan of the church.

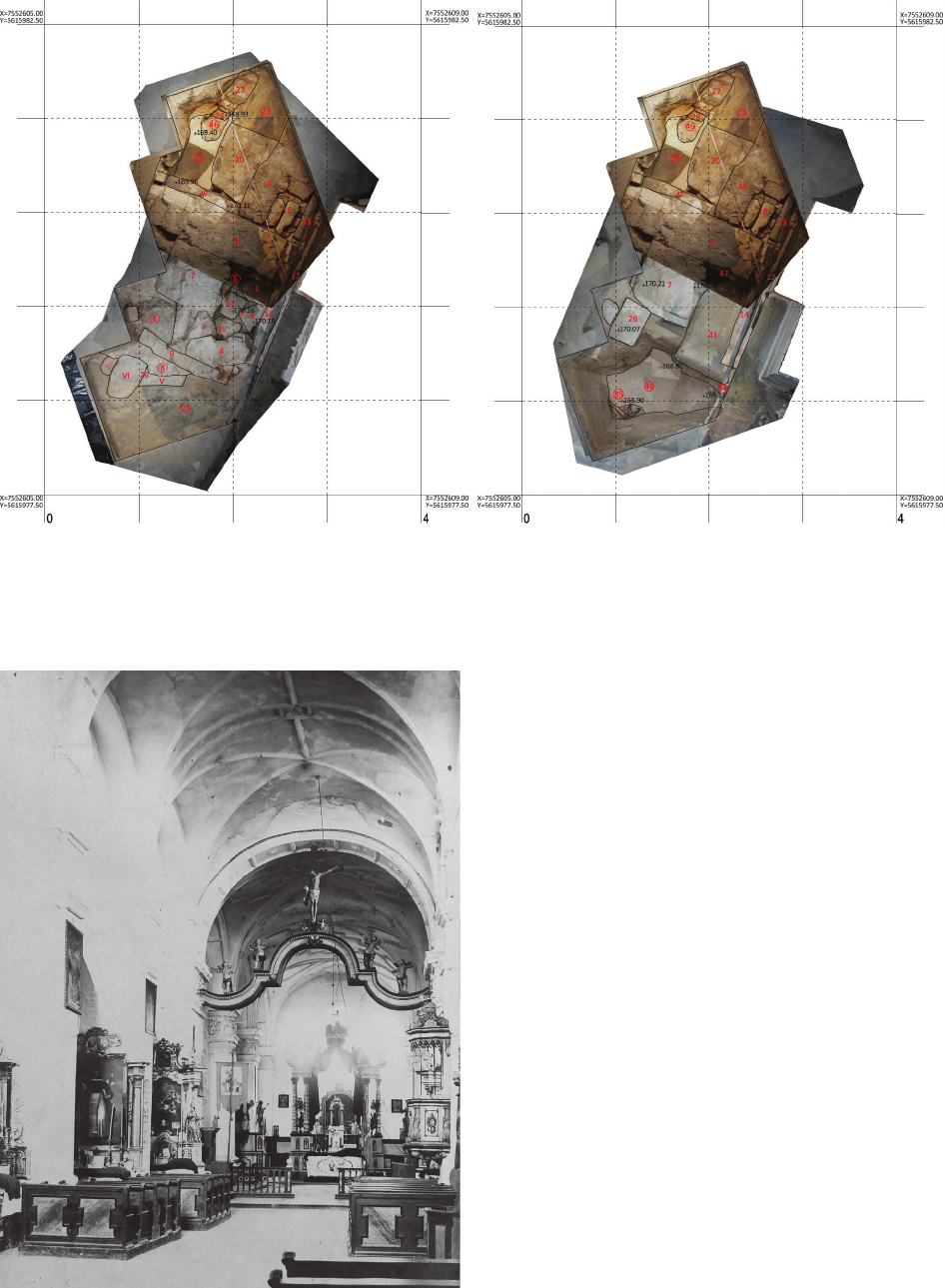

Apart from these elements, three additional, irregularly

shaped stone plates were uncovered 11 cm above (coor-

dinates +170.16, +170.18). These elements were arranged

loosely, serving as lling (k. 5, I–IV); one featured a dis-

tinctive circular indentation (Fig. 10). Marek Florek re-

vealed similar plates during his archaeological works car-

ried out inside the church between the years 1991–1992.

Three usable levels of ooring were identied at the time

at excavation site number 4 – apart from the contemporary

and “late Romanesque” (dating back to the period when

the church was constructed, second quarter of the 13

th

century, situated directly on the pillar foundation), also

the modern one (originating from the 2

nd

half of the 17

th

century, around 1670, preserved as a stone slab and bricks

with traces of engove on the pillar’s eastern face) (Florek

1993, 136, 127, 132). Stone slabs were also uncovered at

excavation site 9, documented 17 cm below the current

ooring’s level (the researcher believes the ooring dates

back to the 2

nd

half of the 19

th

century, supplemented with

early 20

th

-century llings) (Florek 1993, 131, 133, 135).

Several fragments of medieval and modern pottery

were also discovered in the excavation (including a piece

of a 17

th

-century glazed strainer), as well as fragments of

glass and brick, con nails, and other small iron items.

Conclusions

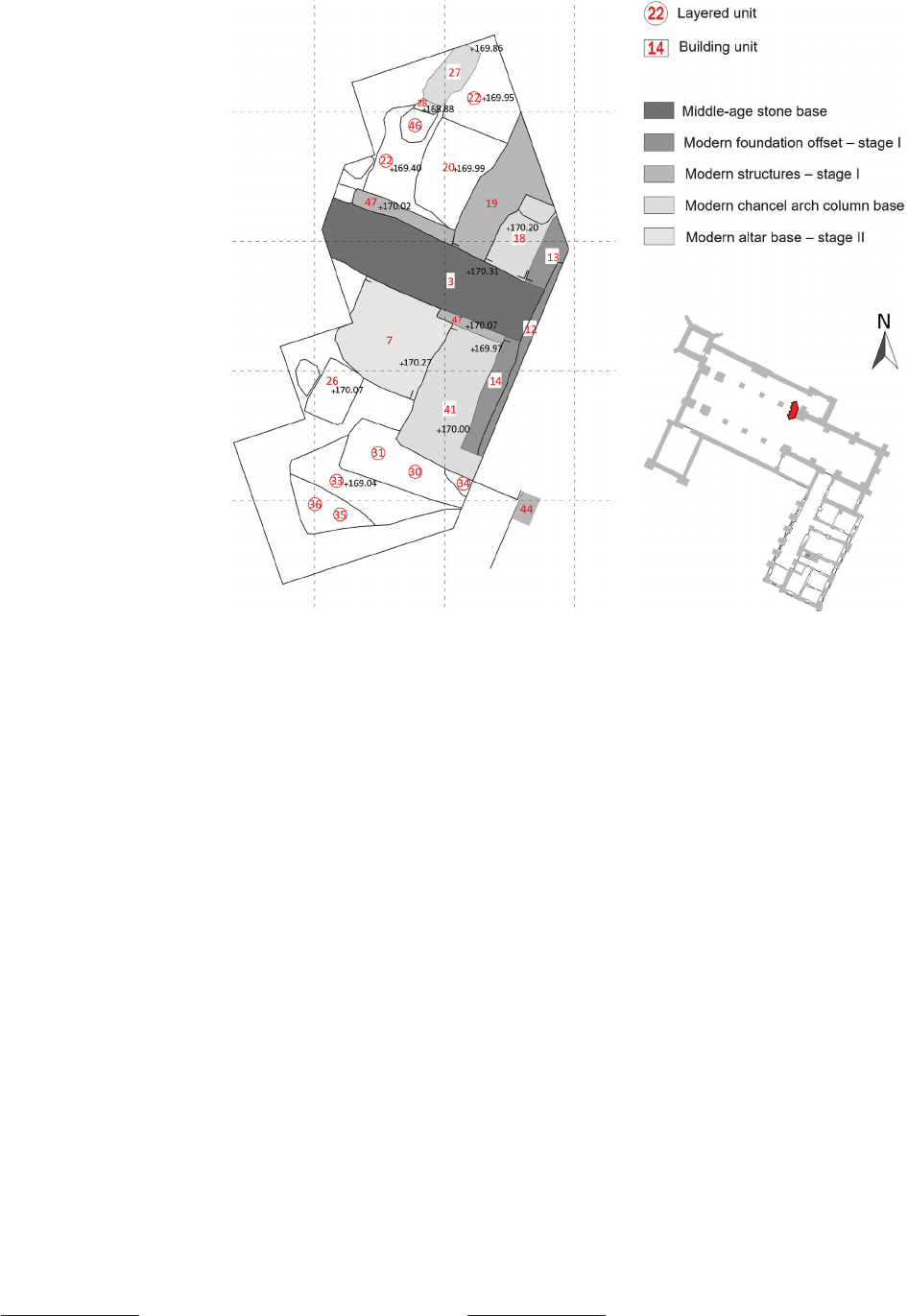

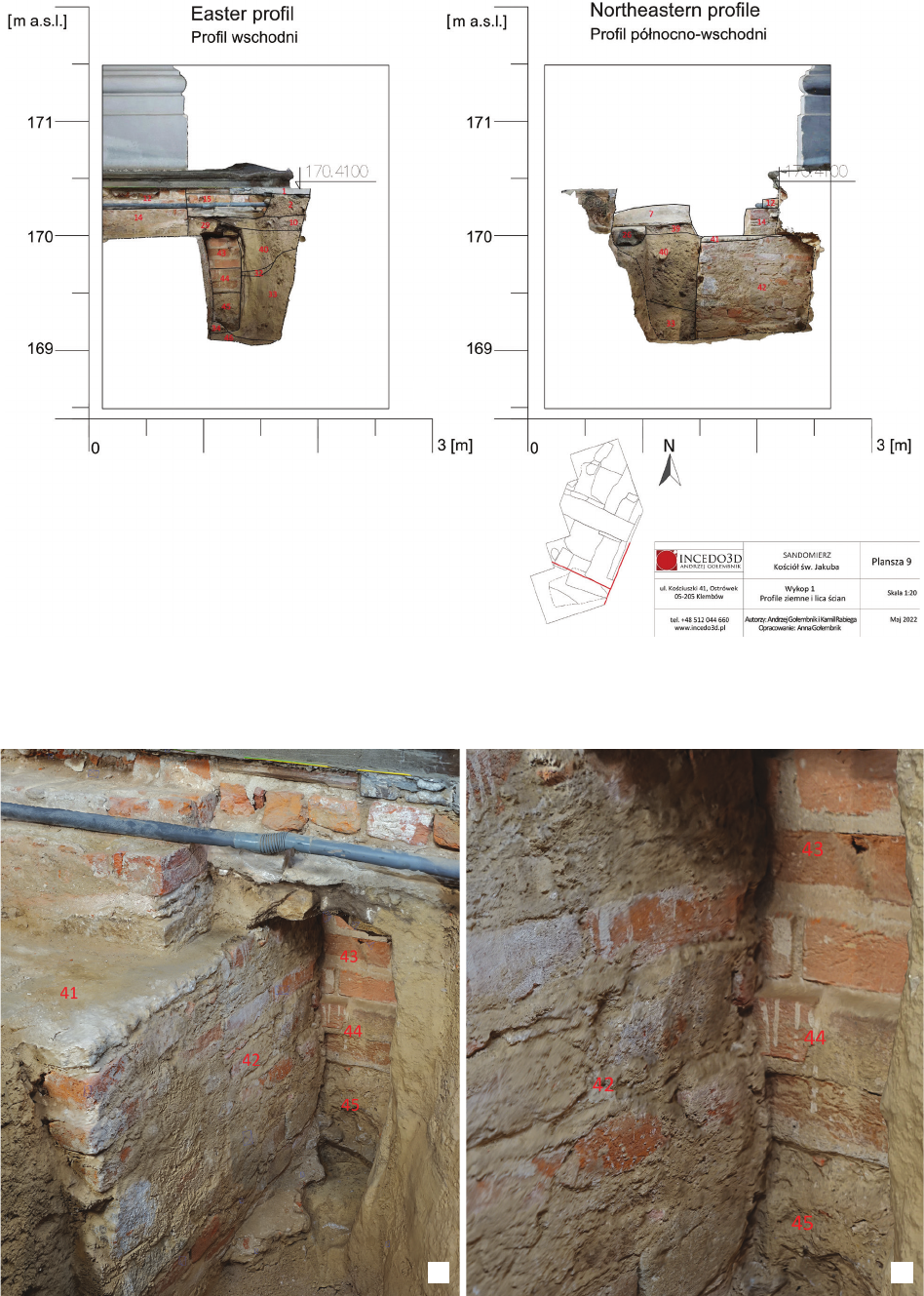

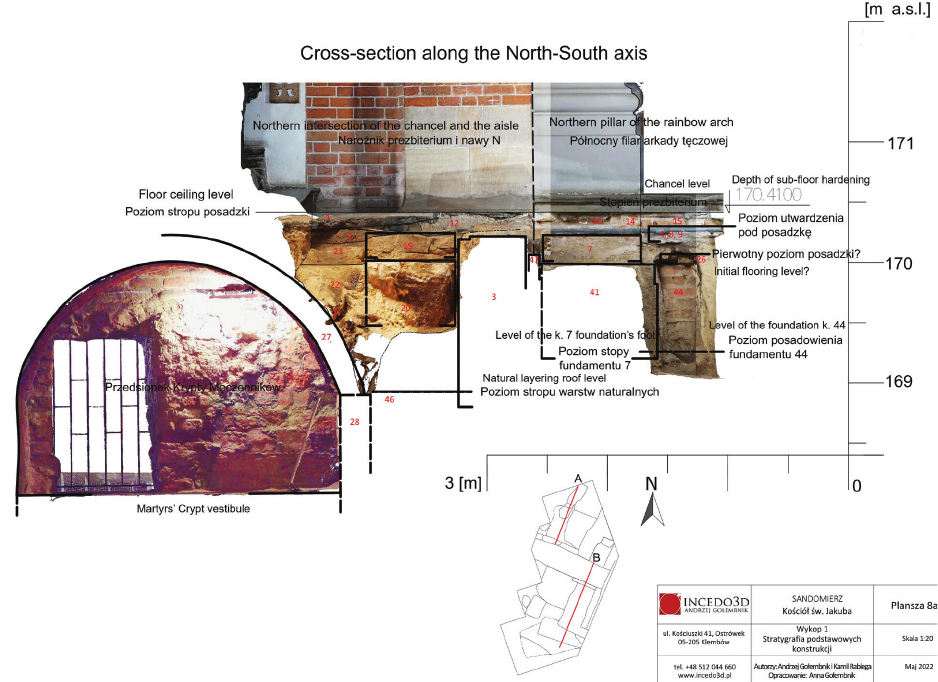

The correlation of the layers documented in the exca-

vation does not create a coherent sequence, thus it cannot

serve as a basis for denitive chronological determina-

tions. The sole legible joints include: the perimeter of the

construction trench beneath the foundation mass k. 41/42,

and the excavation under the partially deteriorated tomb

pit, visible in the virgin soil by to the southern edge of

the probing site (k. 35–36) (Fig. 4b). Preliminary dating

must therefore be based on the correlation between the

walls and the dimensions of the uncovered bricks, where-

as the conclusions presented below should be perceived

as an initial recognition. The unearthed brick structures,

architectural detail, and evidence of numerous excava-

tions indicate that the examined section of the church has

undergone a number of changes throughout the ages and

was also intensely used for burial purposes.

It is plausible that the presence of a choir partition was

related to the initial phase of the functioning of the Do-

minican church. Perhaps a fragment of this construction

(in the foundation section) was identied on the eastern

side of the excavation at the intersection of the main nave

and the chancel (k. 43/44). The positioning along the line

beneath the chancel arch could serve as a proof of such

a role (moreover, it would prove dicult to justify the

construction of a wall at this spot during each of the sub-

sequent reconstructions of the church). Conversely, the

rationale for assigning an early date to the structure (at

around mid-13

th

century) stems from the fact that, based

on stratigraphy, it had been constructed before the foun-

dation of the pillar which holds the weight of the arch ar-

cade; the excavation also aected the burial sites in this

area. The hypothesis is further substantiated by the con-

gruence of the dimensions of the exposed bricks and those